Feminism in Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Am Not a Woman Writer’ About Women, Literature and Feminist Theory Today FT

259-271 095850 Moi (D) 4/9/08 09:39 Page 259 259 ‘I am not a woman writer’ About women, literature and feminist theory today FT Feminist Theory Copyright 2008 © SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, and Washington DC) vol. 9(3): 259–271. 1464–7001 DOI: 10.1177/1464700108095850 Toril Moi Duke University http://fty.sagepub.com Abstract This essay first tries to answer two questions: Why did the question of the woman writer disappear from the feminist theoretical agenda around 1990? Why do we need to reconsider it now? I then begin to develop a new analysis of the question of the woman writer by turning to the statement ‘I am not a woman writer’. By treating it as a speech act and analysing it in the light of Simone de Beauvoir’s understanding of sexism, I show that it is a response to a particular kind of provocation, namely an attempt to force the woman writer to conform to some norm for femininity. I also show that Beauvoir’s theory illuminates Virginia Woolf’s strategies in A Room of One’s Own before, finally, asking why we, today, still should want women to write. keywords J. L. Austin, Simone de Beauvoir, femininity, feminist literary criticism, literature, women writers, Virginia Woolf Why is the question of women and writing such a marginal topic in feminist theory today? The decline of interest in literature is all the more striking given its central importance in the early years of feminist theory. Although I shall only speak about literature, I think it is likely that the loss of interest in literature is symptomatic of a more wide-ranging loss of interest in questions relating to women and aesthetics and women and creativity within feminist theory. -

Breaking Boundaries: Women in Higher Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 418 637 HE 031 166 AUTHOR Morley, Louise, Ed.; Walsh, Val, Ed. TITLE Breaking Boundaries: Women in Higher Education. Gender and Higher Education Series. ISBN ISBN-0-7484-0520-8 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 239p. AVAILABLE FROM Taylor & Francis, 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007-1598; phone: 800-821-8312; fax: 215-785-5515 ($24.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Activism; Age Differences; Aging (Individuals); Blacks; Business Administration Education; Careers; Change Agents; College Faculty; Deafness; Disabilities; Educational Trends; Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Females; *Feminism; Foreign Countries; Graduate Study; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; Mothers; Older Adults; Sex Differences; *Sex Discrimination; Sex Fairness; Teacher Attitudes; Trend Analysis; Women Faculty; *Womens Education IDENTIFIERS United Kingdom ABSTRACT Essays from women in higher education, organized around two major themes: diversity, equity, and change, and feminism in the academy, and with an emphasis on these issues in the United Kingdom, include: "Women and Careers in Higher Education: What Is the Problem?" (Christine Heward); "In the Prime of Their Lives? Older Women in Higher Education" (Meg Maguire); "Activists as Change Agents: Achievements and Limitations" (Liz Price and Judy Priest); "Good Practices, Bad Attitudes: An Examination of the Factors Influencing Women's Academic Careers" (Jane Kettle); "Deaf Women Academics in Higher Education" (Ruth-Elaine -

APÉNDICE BIBLIOGRÁFICO1 I. Herederas De Simone De Beauvoir A. Michèle Le Doeuff -Fuentes Primarias Le Sexe Du Savoir, Aubier

APÉNDICE BIBLIOGRÁFICO1 I. Herederas de Simone de Beauvoir A. Michèle Le Doeuff -Fuentes primarias Le sexe du savoir, Aubier, Paris : Aubier, 1998, reedición: Champs Flammarion, Paris, 2000. Traducción inglesa: The Sex of Knowing. Routledge, New-York, 2003. L'Étude et le rouet. Des femmes, de la philosophie, etc. Seueil, Paris, 1989. Tradcción inglesa: Hipparchia's Choice, an essay concerning women, philosophy, etc. Blackwell, Oxford, 1991. Traducción española: El Estudio y la rueca, ed. Catedra, Madrid, 1993. L'Imaginaire Philosophique, Payot, Lausanne, 1980. Traducción inglesa: The Philosophical Imaginary, Athlone, London, 1989. The Philosophical Imaginary ha sido reeditado por Continuum, U. K., 2002. "Women and Philosophy", en Radical Philosophy, Oxford 1977; original francés en Le Doctrinal de Sapience, 1977; texto inglés vuelto a publicar en French Feminist Thought, editado por Toril Moi, Blackwell, Oxford 1987. Ver también L'Imaginaire Philosophique o The Philosophical Imaginary, en una antología dirigida por Mary Evans, Routledge, Londres. "Irons-nous jouer dans l'île?", en Écrit pour Vl. Jankélévitch, Flammarion, Flammarion, 1978. "A woman divided", Ithaca, Cornell Review, 1978. "En torno a la moral de Descartes", en Conocer Descartes 1 Este apéndice bibliográfico incluye las obras de las herederas de Simone de Beauvoir, así como las de Hannah Arendt y Simone Weil, y algunas de las fuentes secundarias más importantes de dichas autoras. Se ha realizado a través de una serie de búsquedas en la Red, por lo que los datos bibliográficos se recogen tal y como, y en el mismo orden con el que se presentan en las diferente páginas visitadas. y su obra, bajo la dirección de Victor Gomez-Pin, Barcelona 1979. -

Chapter One Towards a Feminist Reading

Chapter One Towards a Feminist Reading The advent of feminism as a global and revolutionary ideology has brought into the field of literary criticism new critical outlooks and modes of exegesis. The practice of reading of any literary text has become a site in the struggle for change in gender relations that prevail in society. A reading that is feminist aims at asking such rudimentary questions: how the text defines sexual questions, what it says about gender relations and how it represents women. In other words, feminist reading/criticism has come to be recognized as a political discourse: a critical and theoretical practice committed to the struggle against patriarchy and sexism. The influential feminist critic, Elaine Showalter points out that two factors - gender and politics- which are suppressed in the dominant models of reading gain prominence with the advent of a feminist perspective. In every area of critical reflection whether it is literary representations of sexual difference or the molding/shaping of literary genres by masculine values feminist criticism has established gender as a fundamental category of literary analysis. With ,gender as a tool of literary interpretation the issue of silencing of the female voice in the institutions of literature, criticism and theory has also come to the forefront. Appreciating the widespread importance of gender, feminist philosophers resist speaking in gender-neutral voice. They value women's experiences, interest, and seek to shift the position of women from object to one of subject and agent. 1 Moreover, it has been an important function of feminist criticism to redirect attention to personal and everyday experience of alienation and oppression of women (as reflected in literary texts). -

FEMINIST LITERARY THEORY a Reader

FEMINIST LITERARY THEORY A Reader Second Edition Edited by Mary Eagleton P u b I i s h e r s Contents Preface xi Acknowledgements xv 1 Finding a Female Tradition Introduction 1 Extracts from: A Room of One's Own VIRGINIA WOOLF 9 Literary Women ELLEN MOERS 10 A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte to Lessing ELAINE SHOW ALTER 14 'What Has Never Been: An Overview of Lesbian Feminist Literary Criticism' BONNIE ZIMMERMAN 18 'Compulsory Heterosexuality andXesbian Existence' ADRIENNE RICH 24 'Saving the Life That Is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist's Life ALICE WALKER 30 Title Essay In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens ALICE WALKER 33 Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory CHRIS WEEDON 36 'Race and Gender in the Shaping of the American Literary Canon: A Case Study from the Twenties' PAUL LAUTER 39 Women's Oppression Today: Problems in Marxist Feminist Analysis MICHELE BARRETT 45 'Writing "Race" and the Difference it Makes' HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR 46 'Parables and Politics: Feminist Criticism in 1986' NANCY K. MILLER 48 Reading Woman: Essays in Feminist Criticism MARY JACOBUS 51 'Happy Families? Feminist Reproduction and Matrilineal Thought' LINDA R. WILLIAMS 52 'What Women's Eyes See' VIVIANE FORRESTER 56 'Women and Madness: The Critical Phallacy' SHOSHANA FELMAN 58 vi CONTENTS 'French Feminism in an International Frame' GAYATRI CHAKRAVORTY SPIVAK 59 Feminist Literary History: A Defence JANET TODD 62 2 Women and Literary Production Introduction 66 Extracts from: A Room of One's Own VIRGINIA WOOLF 73 'Professions for, Women' VIRGINIA WOOLF 78 Silences TILLIE OLSEN 80 'When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision' ADRIENNE RICH 84 The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination SANDRA M. -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy..................................................................................... -

Simone De Beauvoir

The Cambridge Companion to SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR Edited by Claudia Card University of Wisconsin published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, UnitedKingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception andto the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printedin the UnitedKingdomat the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Trump Medieval 10/13 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge companion to Simone de Beauvoir / edited by Claudia Card. p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 79096 4 (hardback) – isbn 0 521 79026 3 (paperback) 1. Beauvoir, Simone de, 1908–1986. I. Card, Claudia. II. Series. b2430.b344c36 2002 194 –dc21 2002067378 isbn 0 521 79096 4 hardback isbn 0 521 79429 3 paperback contents List of tables page xi Notes on contributors xii Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii List of abbreviations xxiii Introduction 1 claudia card 1 Beauvoir’s place in philosophical thought 24 barbara s. andrew 2 Reading Simone de Beauvoir with Martin Heidegger 45 eva gothlin 3 The body as instrument and as expression 66 sara heinamaa ¨ 4 Beauvoir andMerleau-Ponty on ambiguity 87 monika langer 5 Bergson’s influence on Beauvoir’s philosophical methodology 107 margaret a. -

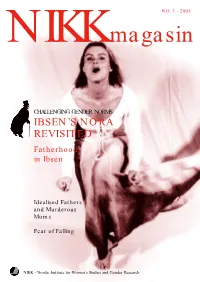

Ibsen's Nora Revisited

NO. 3 - 2005 NIKK magasin CHALLENGING GENDER NORMS IBSEN’S NORA REVISITED Fatherhood in Ibsen Idealised Fathers and Murderous Moms Fear of Falling NIKK - Nordic Institute for Women's Studies and Gender Research Photo: Leif Gabrielsen Why Ibsen is still important The year 2006 marks the 100th anniversary of the death of the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen.Throughout this year, a wide range of events will be arranged all over the world, highlighting the importance of Ibsen’s legacy and providing opportunities for fresh interpretations of his work. Ibsen proclaims the freedom of the individual:“For me freedom is the greatest and highest condition for life”, Ibsen wrote in a letter in 1882. He has made generations reflect on fundamental rights and values. Many of the social and personal conflicts in his plays are still relevant, as are the gender norms he challenges when he lets Nora leave because she no longer wants to live the confined life of a doll. Even today, some of his texts are censured and some of his plays prohibited in parts of the world. Toril Moi, Professor of Literature at Duke University, USA and originally from Norway, says that Ibsen’s literary work is unique because he is perhaps the only male author of the 1800s who perceived the situation of women to be at least as interesting as that of men, in both a philosophical and dramatic sense.As part of the ten-year anniversary of NIKK Toril Moi gave a lecture at the University of Oslo on November 28 entitled “’First and foremost a human being: Gender, body and theatre in A Doll’s House”. -

View / Download 2.6 Mb

Utopian (Post)Colonies: Rewriting Race and Gender after the Haitian Revolution by Lesley Shannon Curtis Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Deborah Jenson, Supervisor ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Toril Moi ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Philip Stewart Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Utopian (Post)Colonies: Rewriting Race and Gender after the Haitian Revolution by Lesley Shannon Curtis Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Deborah Jenson, Supervisor ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Toril Moi ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Philip Stewart An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v Copyright by Lesley Shannon Curtis 2011 Abstract ‚Utopian (Post)Colonies: Rewriting Race and Gender after the Haitian Revolution‛ examines the works of French women authors writing from just before the first abolition of slavery in the French colonies in 1794 to those writing at the time of the second and final abolition in 1848. These women, each in different and evolving ways, challenged notions of race and gender that excluded French women from political debate and participation and kept Africans and their descendants in subordinated social positions. However, even after Haitian independence, French authors continued to understand the colony as a social and political enterprise to be remodeled and ameliorated rather than abandoned. -

ABSTRACTS 22 June Session 1: 09:00 – 10:00 Critique / Postcritique I

(Last update: 30 May 2021) ABSTRACTS 22 June Session 1: 09:00 – 10:00 Critique / Postcritique I Magnus Ullén, Stockholm University Historicizing Post-Critique: Reading in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism Lately, several critics have argued the importance of highlighting the affective dimension of reading, and have declared the existing paradigm of “critical reading” insufficient to that end. In its place, Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus have called for “surface reading”, Rita Felski for a neo-phenomenology informed by the actor-network theory of Bruno Latour, and Toril Moi for a mode of ordinary reading she traces to late Wittgenstein. A peculiar feature of these attempts at post-critical reading practices is that they seem much more adept at exposing the limits of existing forms of reading than with demonstrating the advantages of the alternative ways of reading they supposedly introduce. Felski, for instance, has written two books deploring the reading practices of “critique” without offering any readings of her own; Moi’s case for ordinary reading is equally void of productive readings of literary texts. These circumstances suggest the need for historicizing the calls for post-critical modes of reading. The present talk suggests that the medieval quadriga, which maps reading over four interconnected levels – literal (historical), allegorical, tropological (aesthetic), and anagogical (ideological) – may help us do so. It goes on to argue that post-critique is marked by a regression to the tropological aspect of the text, and that this circumstance suggests an unwillingness to confront the question of how our individual understanding of the text is interpellated, as it were, by the ideological machinery of the anagogical level, precisely at the moment when that interpellation has become so compelling as to make “free” reading virtually impossible. -

The Second 'Second Sex' - the Chronicle Review - the Chronicle of Higher Education Date: June 24, 2010 10:13:30 PM EDT To: [email protected] 5 Attachments, 18.2 KB

From: Toril Moi <[email protected]> Subject: The Second 'Second Sex' - The Chronicle Review - The Chronicle of Higher Education Date: June 24, 2010 10:13:30 PM EDT To: [email protected] 5 Attachments, 18.2 KB From Evernote: The Second 'Second Sex' - The Chronicle Review - The Chronicle of Higher Education Clipped from: http://chronicle.com/article/The-Second-Second-Sex/65962/ Log In | Create a Free Account | Subscribe Now = Premium Content Thursday, June 24, 2010 Subscribe Today! HOME NEWS OPINION & IDEAS FACTS & FIGURES TOPICS JOBS ADVICE FORUMS EVENTS The Chronicle Review Commentary Brainstorm Books Letters to the Editor Academic Destinations Campus Viewpoints The Chronicle Review Home Opinion & Ideas The Chronicle Review E-mail Print Comment (10) Share June 20, 2010 The Second 'Second Sex' By Carlin Romano A book is not born, but rather becomes, a translation. The latter may be a creative reimagining of the original, a faithful mirror image, an imperfect rendering, even a scandalous distortion. Depending on one's concrete connection to the act of literary alchemy—professional translator, delighted or bemused author, satisfied or enraged Henri Cartier-Bresson, Magnum Photos publisher, savvy or naïve reader—serenity or Simone de Beauvoir, Paris, 1945 mayhem may ensue. Enlarge Image All sorts of practical factors affect a translation. Doing one may make no financial sense, or so little sense that a publisher who goes ahead may make every effort to keep costs down. A work may be peculiarly intractable thanks to rampant colloquialism, great length, or recondite local detail. An author may be cooperative, useless, or permanently useless (that is, dead). -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un versity o f W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2001 Published by Phyllis HolmanWeisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing ofcontents Volume 21, Number 3 Fall 2001 Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the U(liversity of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum offeminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from currentissues ofmajor feministjournals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first pUblication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. 5. Current editor. 6. Editorial address (if different from SUbscription address).