Szymon Askenazy As a Diplomat of the Reborn Poland (1920–1923)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Східноєвропейський Історичний Вісник East European Historical Bulletin

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДРОГОБИЦЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DROHOBYCH IVAN FRANKO STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY ISSN 2519-058X (Print) ISSN 2664-2735 (Online) СХІДНОЄВРОПЕЙСЬКИЙ ІСТОРИЧНИЙ ВІСНИК EAST EUROPEAN HISTORICAL BULLETIN ВИПУСК 12 ISSUE 12 Дрогобич, 2019 Drohobych, 2019 Рекомендовано до друку Вченою радою Дрогобицького державного педагогічного університету імені Івана Франка (протокол від 29 серпня 2019 року № 8) Наказом Міністерства освіти і науки України збірник включено до КАТЕГОРІЇ «А» Переліку наукових фахових видань України, в яких можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук у галузі «ІСТОРИЧНІ НАУКИ» (Наказ МОН України № 358 від 15.03.2019 р., додаток 9). Східноєвропейський історичний вісник / [головний редактор В. Ільницький]. – Дрогобич: Видавничий дім «Гельветика», 2019. – Вип. 12. – 232 с. Збірник розрахований на науковців, викладачів історії, аспірантів, докторантів, студентів й усіх, хто цікавиться історичним минулим. Редакційна колегія не обов’язково поділяє позицію, висловлену авторами у статтях, та не несе відповідальності за достовірність наведених даних і посилань. Головний редактор: Ільницький В. І. – д.іст.н., доц. Відповідальний редактор: Галів М. Д. – к.пед.н., доц. Редакційна колегія: Манвідас Віткунас – д.і.н., доц. (Литва); Вацлав Вєжбєнєц – д.габ. з історії, проф. (Польща); Дюра Гарді – д.філос. з історії, професор (Сербія); Дарко Даровец – д. фі- лос. з історії, проф. (Італія); Дегтярьов С. І. – д.і.н., проф. (Україна); Пол Джозефсон – д. філос. з історії, проф. (США); Сергій Єкельчик – д. філос. з історії, доц. (Канада); Сергій Жук – д.і.н., проф. (США); Саня Златановіч – д.філос. з етнології та антропо- логії, ст. наук. спів. -

Download File

BEYOND RESENTMENT Mykola Riabchuk Vasyl Kuchabsky, Western Ukraine in Conflict with Poland and Bolshevism, 1918-1923. Translated from the German by Gus Fagan. Edmomton and Toronto: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2009. 361 pp. + 6 maps. t might be a risky enterprise to publish a historical of Western Ukrainians to establish their independent monograph written some eighty years ago, which at republic on the ruins of the Habsburg empire—in full the time addressed the very recent developments of line with the prevailing Wilsonian principle of national I1918-1923—this would seem to be much more suited toself-determination, the right presumably granted by the lively memoirs than a cool-blooded analysis and archival victorious Entente to all East European nations. Western research. Indeed, since 1934 when Vasyl Kuchabsky's Ukraine is in the center of both the title and the narrative, Die Westukraine im Kampfe mit Polen und dem and this makes both the book and its translation rather Bolschewismus in den Jahren 1918-1923 was published important, since there are still very few “Ukrainocentric” in Germany in a small seminar series, a great number of accounts of these events, which though not necessarily books and articles on the relevant topics have appeared, opposing the dominant Polish and Russian perspectives, and even a greater number of archival documents, letters at least provide some check on the myths and biases and memoirs have become accessible to scholars. and challenge or supplement the dominant views with Still, as Frank Sysyn rightly points out in his short neglected facts and alternative interpretations. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

INSIDE: Analysis: Ukraine-Russia prisoner release – page 2 “Steinmeier formula” and Normandy Four – page 3 Diaspora statements support Plast in Ukraine – page 7 THEHEPublished U by theKRAINIANK UkrainianR NationalAIN Association,IAN Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLYEEKLY Vol. LXXXVII No. 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2019 $2.00 Ukraine’s president rejects Zelenskyy’s foreign policy faces challenges state support for Plast scouts: at Normandy Four and U.N. General Assembly Volodymyr Zelenskyy will meet with President Donald What happened and what’s next Trump next week in New York during the opening of the 74th session of the United Nations General Assembly. by Roman Tymotsko Both events have generated considerable speculation KYIV – President Volodymyr Zelenskyy rejected the law and controversy. While potentially providing new opportu- “On state recognition and support of Plast – National nities, they pose a major test for President Zelenskyy and Scouting Organization of Ukraine,” sending it back to the the cohesion and efficacy of his nascent foreign policy, as Verkhovna Rada on September 4. The legislation had been well as the aptitude of his team in this sphere. approved by the previously elected Parliament at the end Russia’s insistence on strict terms for its participation in of May and awaited the president’s action for more than a new Normandy Four summit – namely Ukraine’s accep- three months. tance of the controversial “Steinmeier formula” from 2016 The president did not sign the law; instead, he returned as a precondition – has set off alarm bells. The formula has it to the Parliament with his proposals. -

Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny” Motywy Żydowskie W Polskiej Fotografii Prasowej Okresu Międzywojennego Na Przykładzie „Ilustrowanego Kuryera Codziennego”

Konrad Zieliński UMCS Lublin – PWSZ Zamość [email protected] Jewish themes in the Polish press photography on the example of the „Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny” Motywy żydowskie w polskiej fotografii prasowej okresu międzywojennego na przykładzie „Ilustrowanego Kuryera Codziennego” Summary: „Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny” (Illustrated Daily Courier – IKC) was issued in the years 1910- 1939 in Krakow; the title was the largest Polish newspaper (up to 400,000 copies) in the interwar period. The newspaper and press company named IKC had its branches in the main Polish cities as well as in some European capitals. Every number was read by approximately 1,000,000 readers. IKC was one of few Polish titles where the Jewish themes were regularly presented, also in photography. Photo-archive of IKC is one of the biggest and most important sources of photographs of Jewish life in the interwar Poland. The aim of the article is to present the most typical and frequent „Jewish” motifs in the Polish press and the answer to the question what was the picture of Jews in Poland presented in the newspaper. Keywords: press, Jewish, photography, IKC Streszczenie: „Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny” (IKC) ukazywał się w latach 1910-1939 w Krakowie. W okresie międzywojennym była to największa gazeta w Polsce, której nakład sięgał 400 000 egzemplarzy. IKC, tytuł i potężny koncern prasowy o tej nazwie, utrzymywał korespondentów i oddziały w głównych miastach Polski, a także w niektórych stolicach europejskich. Szacuje się, że każdy egzemplarz czy- tało około miliona osób, a przy tym IKC był jednym z niewielu polskich tytułów, w których tematyka żydowska była regularnie prezentowana, także w fotografii. -

Memory of Stalinist Purges in Modern Ukraine

The Gordian Knot of Past and Present: Memory of Stalinist Purges in Modern Ukraine HALYNA MOKRUSHYNA Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the PdD in Sociology School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Halyna Mokrushyna, Ottawa, Canada, 2018 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Preface ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Research question ............................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Conceptual framework ................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Chapter 2: Social memory framework ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

AUGUST 24 – UKRAINIAN INDEPENDENCE DAY Published by the Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating its 125th anniversary Vol. LXXXVII No. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 25, 2019 $2.00 British investigators: More evidence Leaders of Ukraine and Israel meet found of Russian role in the Donbas in Kyiv, seeking to bolster bilateral ties RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service An EHRAC news release to announce the hiring said, “29 members of a Ukrainian A London-based digital forensics agency volunteer battalion were… surrounded and says it has gathered an enormous body of taken captive by Russian armed forces, and evidence that Russia’s military was transferred into the hands of ‘separatists,’ “ deployed in the August-September 2014 during the battle. fighting around Ilovaisk, in eastern Ukraine, The Guardian reported that 25 of the in which Ukrainian forces were defeated by volunteers were members of the Donbas combined Russian and separatist troops. battalion, whose members were predomi- Forensic Architecture used “machine nantly from the easternmost regions of learning and computer vision” to amass Luhansk and Donetsk when it was formed. “the most comprehensive collection of evi- The Ukrainian prisoners were subse- dence for the presence of Russian military quently “verbally and physically abused, personnel and hardware throughout the stripped of their belongings and… put to battlefield,” its project website states. forced labor” for several months during Russia has denied involvement in the their captivity, the news release alleges. -

Assimilationists Redefined the 1793–1795 in Poland; 1929)

der the title R×kopisy Napoleona. 1793– contempt and abuse. Because historians Like German and French Jews, East Eu- 1795 w Polsce (Napoleonic Manuscripts: who write about Jewish modernization ropean assimilationists redefined the 1793–1795 in Poland; 1929). In addition, rarely use the term with precision, often character of Jewish collective existence. Askenazy wrote the chapters on Russia failing to distinguish between assimila- To create space for their ideological inte- and Poland in the early nineteenth cen- tion as a complex of processes and assimi- gration, they declared that Jews were no tury for second edition of the Cambridge lation as a cultural and political program, longer a separate nation but an organic Modern History (1934). He was also a pas- and because assimilation as an ideologi- part of the larger nation in whose midst sionate chess player. His political career cal project survived the destruction of they lived. Religion alone marked their may have begun when he played against East European Jewry during World War II difference from their neighbors. In 1919, Józef PiËsudski in the Sans Souci café in and continues to haunt the writing of for example, the Association of Poles of Lwów in 1912. He died in Warsaw. Jewish history, it is critical to keep in Mosaic Faith expressed its opposition to mind the difference between these two the Minorities Treaty, with its guarantee • Jozef Dutkiewicz, Szymon Askenazy i jego szkola (Warsaw, 1958); Emil Kipa, “Szymon usages. This article traces the history of of national rights to minorities in the suc- Askenazy,” in Studia i szkice historyczne, groups advocating and promoting assimi- cessor states, on the ground that Polish pp. -

Szymon Askenazy As a Diplomat of the Reborn Poland (1920–1923)

Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej ■ LII-SI(3) Marek Kornat Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History, Polish Academy of Sciences Szymon Askenazy as a diplomat of the Reborn Poland (1920–1923) Zarys treści: Studium jest próbą opracowania działalności dyplomatycznej Szymona Askenazego po odrodzeniu państwa polskiego, a zwłaszcza najmniej znanej karty, jaką była jego walka o kształt granic odrodzonej Rzeczypospolitej w Genewie 1921–1923. Był to jeden z najgorętszych okresów w historii dyplomacji polskiej. Askenazy reprezentował interesy odrodzonej Polski, będącej jego ojczyzną z wyboru. Jego działania nie spotkały się jednak z powszechną aprobatą głównych obozów polityki polskiej. Był też rzecznikiem koncepcji podwójnej świadomości Żydów: żydowskiej i polskiej. Jego zdaniem Żydzi zachować winni swoją religię i kulturę, ale zarazem “niechaj połączą to z poczuciem polskości i patriotyzmu polskiego”. Outline of content: The study is an attempt to describe the diplomatic activities of Szymon Askenazy after the revival of the Polish state, and especially their least known chapter, which was his struggle for the shape of the borders of the reborn Republic of Poland in Geneva, 1921–1923. It was one of the hottest periods in the history of Polish diplomacy. Askenazy represented the interests of the reborn Poland, his chosen homeland. However, his actions did not always receive general approval of the main camps of Polish politics. He was also a spokesperson for the concept of Jews’ double consciousness: Jewish and Polish. In his -

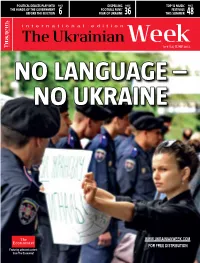

For Free Distribution

POLITICAL DEUCES PLAY INTO PAGE DISPELLING PAGE TOP 12 MUSIC PAGE THE HANDS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOOTBALL FANS' FESTIVALS BEFORE THE ELECTION 6 FEAR OF UKRAINE 36 THIS SUMMER 48 № 9 (32) JUNE 2012 NO LANGUAge – NO UKRAINE WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION Featuring selected content from The Economist Opposition vote |CONTENTS BRIEFING FOCUS ealers 9.8- Russification Redux? Total Political(eimates b yDeuces: A Royal Gift for the Language policy of the TPseudo-oppositionhe Ukrainian Government: A slew of facts party in power puts the projectsWeek) are stealing11.5 signal that the Presidential Ukrainian language the opposition’s Administration is promoting as well as Ukraine’s votes and play Natalia Korolevska’s political sovereignty and European foul in electoral project to help it take control choice at risk 4 commissions 6 of the future parliament 8 POLITICS Why Invest in European Stories: Matej Šurc and Blaž Culture? How Leonidas Donskis Zgaga investigate 5.4 2.9 – 0.4 0.3▪ 0.5- Ukrainian – on the role of0.7 the role of Slovenian officials4.1 are 3.1 1.6 literature and and Ukrainian top distorting storytelling in officials in arms Ukrainian politics trade with the cultureNatalia Hr10omadianska Nasha Oleh Ukrainian Others 12 Balkans 13 Korolevska's pozytsia Ukrayina Liashko's People's (eimates NEIGHBOURS SECURITY Ukrayina - (Civil (Our Radical Party by The The Difficult Vpered! Position) UkrEdwardaine) ChowPart ony how Ukrainian Bernard Path towards (Ukraine - Forwrwaarrdd!)!) Ukrainian authorities Week) Kouchner: Security Reform can decrease If you want to live in Ukraine dependence on Russian in a better world, Support from voters gas, yet put themselves it's all possible intending to vote in the eleion, % 16 in an ever worse 18 in the EU 20 Based position instead 0,0 on Razumkov ECONOMICS Centre poll held INVESTIGATION on 14-19 April 23.3 2012 The Illusion of Reforms26.7 According to Armed and 7.7 10.1 5.7 Based Macroeconomic28.2 Schumpeter: Unpunished: The 0,0 28.6 5.1 on KMIS Stability: why 8.5 The book confirms that10. -

CIUS Dornik PB.Indd

THE EMERGENCE SELF-DETERMINATION, OCCUPATION, AND WAR IN UKRAINE, 1917-1922 AND WAR OCCUPATION, SELF-DETERMINATION, THE EMERGENCE OF UKRAINE SELF-DETERMINATION, OCCUPATION, AND WAR IN UKRAINE, 1917-1922 The Emergence of Ukraine: Self-Determination, Occupation, and War in Ukraine, 1917–1922, is a collection of articles by several prominent historians from Austria, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, and Russia who undertook a detailed study of the formation of the independent Ukrainian state in 1918 and, in particular, of the occupation of Ukraine by the Central Powers in the fi nal year of the First World War. A slightly condensed version of the German- language Die Ukraine zwischen Selbstbestimmung und Fremdherrschaft 1917– 1922 (Graz, 2011), this book provides, on the one hand, a systematic outline of events in Ukraine during one of the most complex periods of twentieth- century European history, when the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires collapsed at the end of the Great War and new independent nation-states OF emerged in Central and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, several chapters of this book provide detailed studies of specifi c aspects of the occupation of Ukraine by German and Austro-Hungarian troops following the Treaty of UKRAINE Brest-Litovsk, signed on 9 February 1918 between the Central Powers and the Ukrainian People’s Republic. For the fi rst time, these chapters o er English- speaking readers a wealth of hitherto unknown historical information based on thorough research and evaluation of documents from military archives in Vienna, -

This Content Downloaded from 128.184.220.23 on Tue, 20 Oct 2015 01:12:10 UTC All Use Subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JEWS in UKRAINIAN LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 128.184.220.23 on Tue, 20 Oct 2015 01:12:10 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JEWS IN UKRAINIAN LITERATURE This content downloaded from 128.184.220.23 on Tue, 20 Oct 2015 01:12:10 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions This page intentionally left blank This content downloaded from 128.184.220.23 on Tue, 20 Oct 2015 01:12:10 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Jews in Ukrainian Literature Representation and Identity Myroslav Shkandrij Yale University Press This content downloaded from 128.184.220.23 on Tue, 20 Oct 2015 01:12:10 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Ehrhardt Roman types by The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shkandrij, Myroslav, – Jews in Ukrainian literature : representation and identity / Myroslav Shkandrij. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Jews in literature. Ukrainian literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PG .J S .Ј4—dc A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z . -

Political Murder and the Victory of Ethnic Nationalism in Interwar Poland

POLITICAL MURDER AND THE VICTORY OF ETHNIC NATIONALISM IN INTERWAR POLAND by Paul Brykczynski A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Brian Porter-Szűcs, Chair Professor Ronald G. Suny Professor Geneviéve Zubrzycki Professor Robert Blobaum, University of West Virginia DEDICATION In memory of my Grandfather, Andrzej Pieczyński, who never talked about patriotism but whose life bore witness to its most beautiful traditions and who, among many other things, taught me both to love the modern history of Poland and to think about it critically. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In a project such as this, there are innumerable people to thank. While I know that this list will never be comprehensive, I will nevertheless do my best to acknowledge at least some of those without whom this work would not have been possible. Most important, there will never be a way to adequately thank my wife and best friend, Andrea, for standing by me 150% through this long and often difficult journey. Working on a PhD certainly has its ups and downs and, without Andrea, I would not have made it through the latter. Her faith in my work and in the path I had chosen never wavered, even when mine occasionally did. With that kind of support, one can accomplish anything one set one’s mind to. An enormous thank you must go to my parents, Mikołaj and Ewa Brykczyński. Despite being uprooted from their culture by the travails of political emigration, they somehow found the strength to raise me with the traditions of the Central European Intelligentsia—that is to say in an environment where books were read, ideas were discussed, and intellectual curiosity was valued and encouraged.