Iugerum Usuale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

B. 2.1.0 SZMSZ 03.Változat

BALATONBOGLÁRI DR. TÖRÖK SÁNDOR EGÉSZSÉGÜGYI KÖZPONT 8630 Balatonboglár, Vikár B. u. 4. (((/Fax: 85/550-464 E-mail cím: [email protected] SZERVEZETI ÉS M ŰKÖDÉSI SZABÁLYZAT Hatályba helyezte: Dr. Balázs Lajos intézményvezet ő Ezen dokumentáció a Balatonboglári Dr. Török Sándor Egészségügyi Központ szellemi tulajdona, sokszorosítása intézményvezet ő f őorvos engedélyéhez kötött. Változat: 03 Kiadás dátuma: 2014.04.01. Oldalszám: 1 / 17 I. ÁLTALÁNOS BEVEZET Ő RENDELKEZÉSEK A Balatonboglári Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal közigazgatási területén, ill. vonzáskörzetében a lakosság járó beteg szakellátást igényl ő, gyógyító-megel őző egészségügyi beavatkozásait, a háziorvosi ügyeleti szolgálatát és az ezekkel járó gazdasági feladatokat, munkamegosztásban az önkormányzat pénzügyi osztályával, a Balatonboglári Dr. Török Sándor Egészségügyi Központ elnevezés ű, önkormányzati intézmény végzi, illetve az intézmény ad helyet a balatonboglári alapellátásoknak a 8630 Balatonboglár, Vikár Béla u. 4. alatti ingatlanban Az intézmény neve , székhelye: Balatonboglári Dr. Török Sándor Egészségügyi Központ 8630 Balatonboglár, Vikár Béla u. 4. Az intézmény fenntartója : Balatonboglári Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Az intézmény felügyeleti szerve : Balatonboglári Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Képviselő-testülete Az intézmény jogállása: Balatonboglári Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Képvisel ő-testülete 337/2013. (XII.05.) KT számú határozatával önállóan m űköd ő, de nem önállóan gazdálkodó költségvetési szerv. Az intézmény típusa: Egészségügyi szolgáltató intézmény -

Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán És a Környező Falvak Példáján

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kaposvári Egyetem Folyóiratai / Kaposvar University: E-Journals Act Sci Soc 34 (2011): 181–196 Falucsúfolók, szállóigék és a falvak egymás közti divatja: Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán és a környező falvak példáján Lanszkiné Széles Gabriella Abstract Village-flouting, adages, and fashion differences between villag- es: an example of Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán, and the surrounding villages. The pop- ulation of villages has made no secret of their views about other communities; either it was a good or a bad judgment. Opinions formed of each other enhanced together- ness within their own village. The awareness of differing from the other village – manifested in fashion or action – created a strong connection between community members. The willingness to overtake the neighboring village expressed ambition and skills to advance. The aim of the data collection was to introduce folk costumes, wan- dering stories and the economy of villages based on village-flouting. Even alterca- tions and fights evolved from mockery in the beginning of the last century; but nowa- days these are devoted to the benefit of villages. Today, history is more valued, cele- brations are held in honor to village-flouting, village chorus protect their folk cos- tumes. With collaboration, the traditions of the past live on. Keywords village-flouting, folk costume, wandering stories, anecdote, com- monality, hostility, tradition Bevezetés Fonó község Somogy megye keleti részén, dombos területen, a Kapos-völgyében fekszik, Kaposvár vonzáskörzetéhez tartozik. A község közvetlenül határos északon Kisgyalán, keleten Mosdós, délen Baté, nyugaton Taszár és Zimány községekkel. -

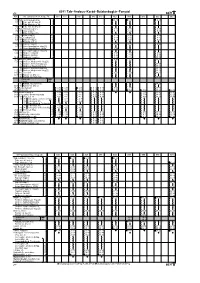

6071 Tab–Andocs–Karád–Balatonboglár–Fonyód 6071 6071

6071 Tab–Andocs–Karád–Balatonboglár–Fonyód 376 6071 Km Dél–dunántúli Közl. Közp. Zrt. 881 871 891 823 813 863 843 853 833 865 0,0 Tab, autóbusz–állomás 6 12 6 45 9 30 0,2 0,0 Tab, aut. áll. bej. út 0,9 Tab, Munkás u. 28. 0,2 0,0 Tab, aut. áll. bej. út 1,1 Tab, Kossuth Lajos u. 6 13 6 47 9 37 2,4 0,0 Zalai elág.[2] 6 15 6 49 9 39 3,2 Zala, Bótapuszta 2,4 0,0 Zalai elág.[2] 6 6 15 6 49 9 39 5,2 Tab, Csabapuszta 0 6 18 6 52 9 42 5,8 0,0 Kapolyi elág.[1] 7 6 19 6 53 9 43 1,6 Kapoly, aut. vt. 0 5,8 0,0 Kapolyi elág.[1] 6 19 6 53 9 43 8,7 0,0 Somogymeggyesi elág.[3] 4,8 Somogymeggyes, iskola 6 30 8,7 0,0 Somogymeggyesi elág.[3] 12,3 0,0 Nágocsi elág.[3] 6 40 7 03 9 51 2,8 Nágocs, faluház 6 44 7 07 9 57 16,8 6,2 Andocs, templom 6 48 7 12 10 02 16,8 Andocs, templom 6 49 7 13 10 02 17,2 0,0 Andocs, toldipusztai elág.[3] 1,3 Andocs, Németsűrűpuszta 10 05 3,2 Andocs, Nagytoldipuszta 10 08 1,3 Andocs, Németsűrűpuszta 10 10 17,2 0,0 Andocs, toldipusztai elág.[3] 10 13 18,5 Andocs, felső 6 51 7 16 10 15 23,1 0,0 Karád, vá. -

Dél-Dunántúli Statisztikai Tükör 2013/3

2013/24 Összeállította: Központi Statisztikai Hivatal www.ksh.hu VII. évfolyam 24. szám 2013. március 26. Dél-dunántúli statisztikai tükör 2013/3 váltották fel. A termelés mennyiségi szemlélete helyébe a minőségi borkészítést célzó kezdeményezések léptek, amelyek jelentősen megvál- Tartalom toztatták a szőlőművelés és borkészítés gyakorlatát. 1 A Dél-Dunántúl borvidékeinek turizmusa Napjainkra az 1980-as évekhez képest mintegy a felére esett vissza mind a termőterület, mind a bortermelés. A szőlőterület méretét az országban 1 A borvidékek rövid bemutatása 81 ezer hektárra regisztrálták 2011-ben, melyből a termőterület 76 ezer hektárt tett ki. Az onnan betakarított összes termés 450 ezer tonna volt, 3 A borvidékek turizmusa melynek mindössze 3,3%-a került étkezési célú felhasználásra. Az orszá- gos szőlőterület 16%-a a Dél-Dunántúlon volt található, mérete 13 ezer 3 Kereskedelmi szálláshelyek hektárt tett ki, 2,2%-kal kisebbet, mint 2005-ben. A szüretelt szőlő meny- nyisége az országosénak 19%-a, 87 ezer tonna volt. Az ebből számított 4 Üzleti célú egyéb szállásadás termésátlag 7300 kg/hektárra adódott, egyharmaddal többre, mint az országos átlag. Magyarországon 2,8 millió hektoliter bort termeltek 2011- 6 Összefoglalás ben, melyből a Dél-dunántúli régió 19%-kal, 531 ezer hektoliterrel része- sedett. Az egy főre jutó éves borfogyasztás országos átlagban 23,4 liter 7 Függelék volt 2010-ben. Hazánk szinte egész területe alkalmas szőlőművelésre. A különböző termő tájak közül kiemelkednek a borvidékek. Borvidéknek nevezik azon területet, melynek klíma és talajviszonyai szőlőtermesztésre alkalmasak, A Dél-Dunántúl borvidékeinek turizmusa ültetvényei összefüggőek, történetileg kialakult, fejlett szőlőművelése van, s az egész területet jellemző karakterű bort ad. A szőlőtermesztésről A borvidékek rövid bemutatása és a borgazdálkodásról szóló 2004. -

Manzate 75 DF

Ikt. sz.: 6300/189-2/2020. Nemzeti Élelmiszerlánc-biztonsági Hivatal Tárgy:Manzate 75 DF gombaölő permetezőszer Növény-, Talaj- és Agrárkörnyezet-védelmi Igazgatóság szükséghelyzeti engedélye dióban, mogyoróban, 1118 Budapest, Budaörsi út 141-145. mandulában (Agrometry Kft.) 1537 Budapest, Pf. 407 Telefon: +36 (1) 309 1000 Ügyintéző: Szabóné Veres Rita [email protected] Oldalak száma:3 portal.nebih.gov.hu Melléklet:1 db, engedélyezett felhasználók listája A Nemzeti Élelmiszerlánc-biztonsági Hivatal (a továbbiakbanMellékletek: :NÉBIH) , mint élelmiszerlánc- felügyeleti szerv, engedélyező hatóság az Agrometry Kft. (2000 Szentendre, Kisforrás u. 30.) ügyfél kérelmére indult hatósági eljárásban meghozta az alábbi HATÁROZATOT. Az engedélyező hatóság a 04.2/2923-2/2012. NÉBIH okiratszámú Manzate 75 DF (750 g/kg mankoceb) gombaölő permetezőszer szükséghelyzeti felhasználását az Agrometry Kft. kérelmére az 1. számú mellékletben megjelölt dió, mogyoró és mandula ültetvényekben 2020. április 1-jétől 2020. július 29-ig engedélyezi. A kérelmező felhasználói körének felelősségére: A Manzate 75 DF gombaölő permetezőszer felhasználható dióban, mandulában és mogyoróban gombás foltbetegségek ellen virágzás és terméskötödés után megelőző módon maximum három alkalommal: - földi kijuttatással dióban, mandulában és mogyoróban 2,1 kg/ha dózisban 600-1000 l/ha permetlével, - kizárólag dióban légi kijuttatással 2,1 kg/ha dózisban 50-60 l/ha permetlével. Dióban, mandulában és mogyoróban előírásszerű felhasználáskor élelmezés-egészségügyi várakozási idő (é.v.i.) 30 nap, a megengedett szermaradék határértéket az Európai Parlament és a Tanács 396/2005/EK rendelete állapítja meg. Légi alkalmazáskor a mező- és erdőgazdasági légi munkavégzésről szóló 44/2005. (V.6.) FVM rendeletben foglaltaknak megfelelően kell eljárni. A légi permetezés csak elsodródás gátló szórófej használatával végezhető, olyan beállítással, amely biztosítja, hogy a kezelendő kultúrára kerülő permetlé cseppek 50 %-os térfogat szerinti átmérője legalább 200 µm. -

February 2009 with the Support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany & the Conference of European Rabbis

Lo Tishkach Foundation European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative Avenue Louise 112, 2nd Floor | B-1050 Brussels | Belgium Telephone: +32 (0) 2 649 11 08 | Fax: +32 (0) 2 640 80 84 E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.lo-tishkach.org The Lo Tishkach European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative was established in 2006 as a joint project of the Conference of European Rabbis and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. It aims to guarantee the effective and lasting preservation and protection of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves throughout the European continent. Identified by the Hebrew phrase Lo Tishkach (‘do not forget’), the Foundation is establishing a comprehensive publicly-accessible database of all Jewish burial grounds in Europe, currently featuring details on over 9,000 Jewish cemeteries and mass graves. Lo Tishkach is also producing a compendium of the different national and international laws and practices affecting these sites, to be used as a starting point to advocate for the better protection and preservation of Europe’s Jewish heritage. A key aim of the project is to engage young Europeans, bringing Europe’s history alive, encouraging reflection on the values that are important for responsible citizenship and mutual respect, giving a valuable insight into Jewish culture and mobilising young people to care for our common heritage. Preliminary Report on Legislation & Practice Relating to the Protection and Preservation of Jewish Burial Grounds Hungary Prepared by Andreas Becker for the Lo Tishkach Foundation in February 2009 with the support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany & the Conference of European Rabbis. -

Pusztaszemes Kt. 2014.01.30. Jkv..Pdf

1 Jegyzokonyv Keszult: Kozseg Kepviselo-testiiletenek 2014. januar 30. napjan tartott nyilvanos uleserol. Jelen vannak: Mecseki Peteme polgarmester lij. Kokonyei Laszlo alpolgarmester, Bolevacz Emone, Pinter Zoltan kepviselok Koselingne dr. Kovacs Zita aljegyzo, Emyes Ervin penziigyi osztalyvezeto Mecseki Peteme polgarmester az iilest megnyitja, megallapitja, hogy a kepviselo-testiilet 5 tagiabol 4 fo jelen van, a kepviselo-testiileti iiles hatarozatkepes, azt megnyitja. Javaslatara a kepviselo-testulet az alabbi napirendet targyalja: Napirend: 1. Pusztaszemes Kozseg 2014. evi koltsegvetese I. fordulo Eloado: Mecseki Peteme polgarmester A kepviselo-testiilet a napirendi javaslatot elfogadta. Napirend targyalasa: 1. Pusztaszemes Kozseg 2014. evi koltsegvetese I. fordulo Eloado: Mecseki Peteme polgarmester Eloterjesztes: irasban Emyes Ervin penziigyi osztalvezeto: A tervzetben a kistersegi tarsulas reszere atadas tevszamai szerepelnek, konkretizalni akkor lehet, ha a kistersegi koltsegvetes elfogadasra keriil. Mar az elozo evben is feladat fmanszirozas tortent, a 2014-es evben egyes tertileteken kis- mertekii emeles lathato pi. a falugondnoki szolgalat eseteben a 2,5 mFt. A miikodokepesseg biztositasahoz tovabbi 5,96 mFt. sziikseges, amelyre palyazatot kell benyujtani. Ez korabban ONHIKI cimen futott, most MUKI roviditett elnevezessel szerepel. A gazdalkodas soran jelentos figyelmet kell forditani a likviditasra, kulonos tekintettel arra, hogy a hivatal mukodesevel kapcsolatos normativa utalasa kozvetleniil Balatonfbldvar reszere tortenik. A targyevi feladatvallalast minimalizalni kell, a kotelezo feladatellatason tul onkent vallalt feladatok, tamogatasok fmanszirozasara csak akkor lesz lehetoseg, ha ennek forras oldala is rendelkezesre all. Mecseki Peteme polgarmester: Szoros gazdalkodast kell folytatni. Mar 2013. evben is igyekeztiink a kiadasokat lefaragni ennek ellenere elmaradasaink vannak. Megoldast atmenetileg a folyoszamlas hitel adhat, de emellett letfontossagii, hogy a tamogatast kapjon az onkormanyzat, ez a mukodokepesseg megorzesenek feltetele. -

(Mol Z), 1939-1945 Rg-39.039M

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Selected Records of the National Land Mortgage Bank of Hungary (MOL Z), 1939‐1945 RG‐39.039M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Tel. (202) 479‐9717 Email: [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Selected Records of the National Land Mortgage Bank of Hungary (MOL Z) Dates: 1939‐1945 Creator: Országos Földhitelintézet Országos Központi Hitelszövetkezet Országos Lakásépítési Hitelszövetkezet Record Group Number: RG‐39.039M Accession Number: 2011.173. Extent: 24 microfilm reels (16 mm) Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Languages: Hungarian, German Administrative Information Access: No restrictions on access. Reproduction and Use: According to the terms of the United States‐Hungary Agreement, personal data of an individual mentioned in the records must not be published sooner than 30 years following the death of the person concerned, or if the year of death is unknown, for 90 years following the birth of the person concerned, or if both dates are unknown, for 60 years following the date of issue of the archival material concerned. "Personal data" is defined as any data that can be related to a certain natural person ("person concerned"), and any conclusion that can be drawn from such data about the person concerned. The full text of the Agreement is available at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives reference desk. 1 http://collections.ushmm.org http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Preferred Citation: RG‐39.039M, Selected Records of the National Land Mortgage Bank of Hungary (MOL Z), 1939‐1945. -

Egyesürpr Alaps Zlr'l''t V L 1Ncvsnces SZERKEZETBEN)

BALAToNFöLovÁru rrsrrnsrct TURISzTIKAI EGyESürpr ALApS zlr'l''t v l 1ncvsncEs SZERKEZETBEN) PREAMBULUM Balatonftildvár Varos turizmusának fellendítéseés fejlesáése érdekében az alábbiakban felsorolt személyek hatérozlék el a Balatonftjldvrári Turisáikai Egyesület alapitását: Bálint Kálmán, Bezeréti Katalin, Bolygóné Polgár Klára, Bóza Attila, Gáspár Imréné,Herencsárné D. Krisztina, Holovits Huba, Holp Jrinosné, Ingár Margit Mária, K,árpáti Péter, Kovács Nándor, Lazi Violetta, Matkovicsné Horváth Krisztina, Molnárné Peringer Erzsébet, Pesti Józsefné, Rucz Roland, Szalkovszki Brigitta,Táírai Roland, Tóth Istvan, Veres István, Veres Istvánné, Veres Zsolt, Y ozár Péter. Az Egyesület 2009. évben működési területét kiterjesztette a Balatonftldvári Kistérségegész területére és a nevét is megváltoztattaennek megfelelően. r. Ár,r.tLÁNoS RENDELKEZE SEK 1. Az egyesület neve: Balatonftildvári KistérségiTurisáikai Egyesület, rövidített neve: BKTE (továbbiakban Egyesület). 2. Az egyesület székhelye: 8623 Balatonfoldvár, Petőfi u. 1. Az egyesület alapítási éve: 2008 Az egyesület működési területe: Balatonloldvriri Kistérségközigazgatási területe Az egyesület körbélyegzőjén köriratban: az Egyesület neve magyarul, a béIyegző közepén: Alapítva 2008 Működése kiterjed Balatonfoldvári Kistérség és vonzáskörzete területére. (települések: Balatonftjldvár, Balatonőszöd, Balatonszárszó, Balatonszemes, Bálványos, Kereki, Kötcse, Kőröshegy, Nagycsepely, Pusztaszemes, Szántód, Szólád, Teleki), melyet, az Egyesület Balatonfijldvári Turisáikai Régió néven kommunikál. -

Hungarian Name Per 1877 Or Onliine 1882 Gazetteer District

Hungarian District (jaras) County Current County Current Name per German Yiddish pre-Trianon (megye) pre- or equivalent District/Okres Current Other Names (if 1877 or onliine Current Name Name (if Name (if Synogogue (can use 1882 Trianon (can (e.g. Kraj (Serbian okrug) Country available) 1882 available) available) Gazetteer) use 1882 Administrative Gazetteer Gazetteer) District Slovakia) Borsod-Abaúj- Abaujvár Füzéri Abauj-Torna Abaújvár Hungary Rozgony Zemplén Borsod-Abaúj- Beret Abauj-Torna Beret Szikszó Zemplén Hungary Szikszó Vyšný Lánc, Felsõ-Láncz Cserehát Abauj-Torna Vyšný Lánec Slovakia Nagy-Ida Košický Košice okolie Vysny Lanec Borsod-Abaúj- Gönc Gönc Abauj-Torna Gönc Zemplén Hungary Gönc Free Royal Kashau Kassa Town Abauj-Torna Košice Košický Košice Slovakia Kaschau Kassa Borsod-Abaúj- Léh Szikszó Abauj-Torna Léh Zemplén Hungary Szikszó Metzenseife Meczenzéf Cserehát Abauj-Torna Medzev Košický Košice okolieSlovakia n not listed Miszloka Kassa Abauj-Torna Myslava Košický Košice Slovakia Rozgony Nagy-Ida Kassa Abauj-Torna Veľká Ida Košický Košice okolie Slovakia Großeidau Grosseidau Nagy-Ida Szádelõ Torna Abauj-Torna Zádiel Košický Košice Slovakia Szántó Gönc Abauj-Torna Abaújszántó Borsod-Abaúj- Hungary Santov Zamthon, Szent- Szántó Zemplén tó, Zamptó, Zamthow, Zamtox, Abaúj- Szántó Moldava Nad Moldau an Mildova- Slovakia Szepsi Cserehát Abauj-Torna Bodvou Košický Košice okolie der Bodwa Sepshi Szepsi Borsod-Abaúj- Szikszó Szikszó Abauj-Torna Szikszó Hungary Sikso Zemplén Szikszó Szina Kassa Abauj-Torna Seňa Košický Košice okolie Slovakia Schena Shenye Abaújszina Szina Borsod-Abauj- Szinpetri Torna Abauj-Torna Szinpetri Zemplen Hungary Torna Borsod-Abaúj- Hungary Zsujta Füzér Abauj-Torna Zsujta Zemplén Gönc Borsod-Abaúj- Szántó Encs Szikszó Abauj-Torna Encs Hungary Entsh Zemplén Gyulafehérvár, Gyula- Apoulon, Gyula- Fehérvár Local Govt. -

A 210/2009. (IX.29.) Kormányrendelet Alapján a Bejelentésköteles Kereskedelmi Tevékenységek És Üzletek Nyilvántartása - Ságvár -Som- Nyim

A 210/2009. (IX.29.) kormányrendelet alapján a bejelentésköteles kereskedelmi tevékenységek és üzletek nyilvántartása - Ságvár -Som- Nyim 5a. Üzleten 7.6. Napi kívüli f ogyasztási 5.4. A kereskedelem cikket 5.3. Üzleten kívüli közlekedési esetén a értékesítő 10.2. Vendéglátó kereskedés és eszközön termék üzlet esetén üzletben a csomagküldő f olytatott f orgalmazása 7.5. Az üzlet az árusítótér vendégek 7.4. 1. kereskedelem értékesítés céljából címe, 7.6. Vásárlók nettó szórakoztatására Vendéglátó Nyilvántar Vállalkozói Kistermelő 5.2. Mozgóbolt esetén a esetében a esetén annak a szervezett 7.3. Üzlet Vásárlók könyve könyve alapterülete, 10.1. zeneszolgáltatás 3. Kereskedő 5.1. Kereskedelmi 6. A kereskedelmi 7.1. Üzleti nyitva üzlet 8.2. Forgalmazott üzletköteles 8.3. Jövedéki termékek 9. Kereskedelmi Külön engedély köteles termékek Engedélyező hatóság Engedély száma, Megkezdésének Megszűnésének tásba 1.2. Iktatószám 2.1. Kereskedő neve 2.2. Kereskedő székhelye nyilvántartási regisztrációs Adószám 4. Statisztikai száma működési terület/útvonal működési terület közlekedési utazás vagy 7.2. Üzlet megnevezése alapterülete nyomtatvány használatba az üzlethez 8.1. Forgalmazott bejelentés-köteles termékek köre Szeszes ital , műsoros Módosításának időpontja cégjegyzékszáma tevékenység címe: tevékenység f ormája tartási ideje esetében termékek köre megnevezése tevékenység jellege köre, megnevezése neve hatály időpontja időpontja vétel száma száma jegyzéke jegyzéke, eszközneka tarott (m2) azonosító adatai vételének létesített kimérés előadás, tánc, bef ogadókép száma érintett megjelölése, rendezvény helyrajzi időpontja gépjármű- szerencsejátékn essége (f ő) települések, amelyen helyének és száma várakozóhely ak nem minősülő országos jelleg kereskedelmi időpontjának, ek száma, szórakoztató megjelölése tevékenységet szervezett azok játék f olytatása. f olytatnak utazás esetén telekhatártól az utazás mért indulási távolsága és 1.2.