Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Panorama's Coverage of 9/11 and the 'War on Terror'

Panorama's coverage of 9/11 and the ‘War on Terror' David McQueen Introduction The BBC requires its journalists to ‘report acts of terror quickly, accurately, fully and responsibly’ (BBC, 2012: 1) yet the Corporation’s flagship current affairs series Panorama’s investigation of the 11 September atrocities and the ensuing ‘War on Terror’ was narrow, factually-flawed and served to amplify hawkish policy prescriptions that ultimately led to ruinous wars against Afghanistan and Iraq. Evidence for this view emerges through an examination of four major investigations into Al-Qaeda and the events of 9-11 broadcast between September 2001 and July 2002. Study of these key episodes shows how Panorama’s coverage lacked investigative depth and drew unfounded links between the 9-11 leader Mohamed Atta and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, whilst contributing to an information vacuum around the attacks that helped feed far-fetched conspiracy theories that sprang up in their aftermath. Other Panorama episodes dealt with the broad subject of terrorism and ‘the War on Terror’ within this period, including three studio debates (‘Britain on the Brink’; ‘War on Terrorism’ and ‘Clash of Cultures’) which have been written about elsewhere (see Cottle, 2002). The focus here, however, is on the quality of the investigative reports that dealt with the traumatic events of September 2001 and their aftermath, events which led to a profound shift in US 1 foreign and security policy, with far-reaching consequences for Britain and the rest of the world (see Norris, Kern and Just, 2003; Moeller, 2004). Context for the Investigations: the Events of 11 September On the morning of 11 September 2001, nineteen militants associated with the Islamic extremist group Al-Qaeda hijacked four American airliners armed with nothing more sophisticated than Stanley knives. -

Battle to Save Children from Gang Terror

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lashmar, P. (2008). From shadow boxing to Ghost Plane: English journalism and the War on Terror. In: Investigative Journalism. (pp. 191-214). Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415441445 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/19055/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203895672 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] From shadow boxing to Ghost Plane: English journalism and the War on Terror In my career as a journalist, there has never been a war on terror but a war of terror. John Pilger.1 “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible….This political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombed from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. -

Study-Guide-For-STUFF-HAPPENS

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION AND THE RATIONALE FOR THE INVASION OF IRAQ One of the most weighty justifications for the United States' 2003 invasion of the Iraqi Republic was the pursuit of Weapons of Mass Destruction (hereafter referred to WMD) by the regime of President Saddam Hussein in violation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 686 & 687. The potential for the Iraqi regime to develop nuclear capability, or that it already held chemical and biological weapons, sat at the forefront of President President George W. Bush Gives a Speech in Cincinatti George W. Bush's rhetoric. In his October 7, 2002 speech at the Cincinatti Museum Center, Bush noted: Tonight I want to take a few minutes to discuss a grave threat to peace, and America's determination to lead the world in confronting that threat. The threat comes from Iraq. It arises directly from the Iraqi regime's own actions -- its history of aggression, and its drive toward an arsenal of terror. Eleven years ago, as a condition for ending the Persian Gulf War, the Iraqi regime was required to destroy its weapons of mass destruction, to cease all development of such weapons, and to stop all support for terrorist groups. The Iraqi regime has violated all of those obligations. It possesses and produces chemical and biological weapons. It is seeking nuclear weapons. It has given shelter and support to terrorism, and practices terror against its own people.1 Or in his March 19, 2003 address to the nation from the Oval Office he began: My fellow citizens, at this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger. -

PDF ('Panorama's Coverage of 9-11 and the War on Terror'')

'Panorama's coverage of 9-11 and the war on terror'’ David McQueen Abstract The BBC's 'flagship' current affairs series Panorama backed away from reporting on the 9-11 attacks despite having a senior reporter with relevant expertise in the area. Subsequent coverage lacked investigative depth, recycled commonplace analogies with Hollywood films and drew unfounded links between the 9-11 leader Mohamed Atta and Iraq. This paper examines Panorama's much criticised coverage of the September 11th attacks, drawing on textual analysis of archival material and interviews to revisit a disturbing chapter in British current affairs coverage. The paper will look specifically at journalistic practices which led to such a failure, including the role of the 'star' reporter, managerial interference, over-reliance on official sources and a culture of caution. It examines how Panorama failed to separate fact from fiction in its use of Hollywood imagery and intelligence services disinformation which contributed to a politically charged atmosphere of fear. It will also closely examine Panorama's claims about the subsequent anthrax attacks which have since been traced back to a US bio-weapons laboratory. These claims which tenuously linked Al Qaeda and foreign powers were staged in highly dramatic ways drawing on horror and science fiction tropes and marked a further blurring of boundaries between fact and fiction. Panorama's coverage, in this respect, was typical of the media's response to the 9-11 atrocities and their aftermath by amplifying fear, echoing official lines of inquiry and avoiding awkward questions, for instance, about the role of domestic agents in the, now all-but-forgotten, anthrax attacks. -

The Military's Role in Counterterrorism

The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hug etortThe LPapers The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hughes Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. hes Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA The Letort Papers In the early 18th century, James Letort, an explorer and fur trader, was instrumental in opening up the Cumberland Valley to settlement. By 1752, there was a garrison on Letort Creek at what is today Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. In those days, Carlisle Barracks lay at the western edge of the American colonies. It was a bastion for the protection of settlers and a departure point for further exploration. Today, as was the case over two centuries ago, Carlisle Barracks, as the home of the U.S. Army War College, is a place of transition and transformation. In the same spirit of bold curiosity that compelled the men and women who, like Letort, settled the American West, the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) presents The Letort Papers. This series allows SSI to publish papers, retrospectives, speeches, or essays of interest to the defense academic community which may not correspond with our mainstream policy-oriented publications. If you think you may have a subject amenable to publication in our Letort Paper series, or if you wish to comment on a particular paper, please contact Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria II, Director of Research, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 632 Wright Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5046. -

Arab Spring” June 2012

A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC’s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” June 2012 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” Contents BBC Trust conclusions 1 Summary 1 Context 2 Summary of the findings by Edward Mortimer 3 Summary of the research findings 4 Summary of the BBC Executive‟s response to Edward Mortimer‟s report 5 BBC Trust conclusions 6 Independent assessment for the BBC Trust by Edward Mortimer - May 2012 8 Executive summary 8 Introduction 11 1. Framing of the conflict/conflicts 16 2. Egypt 19 3. Libya 24 4. Bahrain 32 5. Syria 41 6. Elsewhere, perhaps? 50 7. Matters arising 65 Summary of Findings 80 BBC Executive response to Edward Mortimer’s report 84 The nature of the review 84 Strategy 85 Coverage issues 87 Correction A correction was made on 25 July 2012 to clarify that Natalia Antelava reported undercover in Yemen, as opposed to Lina Sinjab (who did report from Yemen, but did not do so undercover). June 2012 A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” BBC Trust conclusions Summary The Trust decided in June 2011 to launch a review into the impartiality of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring”. In choosing to focus on the events known as the “Arab Spring” the Trust had no reason to believe that the BBC was performing below expectations. -

Foreign Policy Aspects of the War Against Terrorism

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Foreign Policy Aspects of the War against Terrorism Sixth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume II Oral and Written Evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 22 March 2005 HC 36-II Published on 5 April 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Donald Anderson MP (Labour, Swansea East) (Chairman) Mr David Chidgey MP (Liberal Democrat, Eastleigh) Mr Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Rt Hon Andrew Mackay (Conservative, Bracknell) Andrew Mackinlay MP (Labour, Thurrock) Mr John Maples MP (Conservative, Stratford-on-Avon) Mr Bill Olner MP (Labour, Nuneaton) Mr Greg Pope MP (Labour, Hyndburn) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley MP (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Ms Gisela Stuart MP (Labour, Birmingham Edgbaston) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament. Sir Patrick Cormack MP (Conservative, Staffordshire South) Richard Ottaway MP (Conservative, Croydon South) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/foreign_affairs_committee.cfm. -

The New Generation in the Middle East

The New Generation in the Middle East The Third Annual Atkin Conference King’s College London, 21 October 2011 PROGRAMME Friday 21 st October Location: Great Hall, Strand Campus, King’s College London 09.00 Registration and Coffee 09.30 Welcome Amal Abusrour and Sefi Kedmi, Atkin Fellows 09.40 How can diasporas advance peace in the new Middle East? Dr. Hussein Ibish, Executive Director, Hala Salaam Maksoud Foundation for Arab-American Leadership Lorna Fitzsimons, Chief Executive, Bicom Ron Skolnik, Director, Meretz USA Zaki Chehab, Editor-in-Chief, ArabsToday.net Dr Manuel Hassassian, Palestinian Representative to the United Kingdom Moderator: Prof Peter Neumann, ICSR 10.40 The Atkin Fellowship Odelia Englander and Alia Al Kadi, Atkin Fellows 10.50 Coffee Break 11.10 What next for new media in the new Middle East? Michael Young, opinion editor, Daily Star, Lebanon Michael Weiss, communications director, The Henry Jackson Society Malik Abdeh, chief editor, Barada TV, Syria; founder of the Movement for Justice and Development Mahmoud Salem, blogger, Sand Monkey Moderator: Dr John Bew , ICSR 12.15 Buffet Lunch 13.30 A view from Tahrir Square Dr Omar Ashour, Exeter University Dr Amany Soliman, Atkin Fellow Dareen Khalifa, Egyptian Council on Human Rights, Cairo Muna Dajani, Atkin Fellow Moderator: Prof Peter Neumann, ICSR 14.15 A view from the Rothschild tents Gil Murciano, Atkin Fellow, Reut Institute, Tel Aviv Yael Patir, Atkin Fellow, Peres Center for Peace, Tel Aviv Talia Gorodess, Reut Institute, Tel Aviv Moderator: Prof -

Hulu: Under the Hood WE FIND GUESTS for YOUR SHOW

March 2018 Hulu: Under the hood WE FIND GUESTS FOR YOUR SHOW We are television bookers ready to find guests for your show. Guestbooker.com has media trained experts based across the US and the UK in a range of sectors, including; poliics, healthcare, security, law, business, finance and entertainment. Our team is based in London, New York City, Los Angeles, Washington D.C, Nashville, Dallas, Ausin, Miami and Chicago. Journal of The Royal Television Society March 2018 l Volume 55/3 From the CEO It has been an exciting That so many female journalists of Television, don’t miss Mark Lawson’s and illuminating end different ages and backgrounds were insightful profile of the great Macken- to the RTS’s winter among the night’s winners says a lot zie Crook. Meanwhile, our cover looks programme. Despite about the changing times that we are at the rise and rise of Hulu. I, for one, the “Beast from the living in. can’t wait to watch the second season East” bringing snow So, too, did our sold-out early- of The Handmaid’s Tale, coming soon on and ice to even Lon- evening event “Sale or scale”, when Channel 4. don’s Hyde Park Corner, this year’s a high-powered panel analysed the I look forward to seeing many of RTS Television Journalism Awards rapidly consolidating entertainment you at the RTS Programme Awards. generated a lot of genuine warmth. sector. Many thanks to the wonderful This is undoubtedly the most glamor- I’d like to thank everyone who panellists: Kate Bulkley, Mike Darcey, ous night in the RTS calendar. -

Table of Membership Figures For

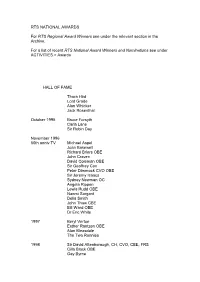

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

Anatomy of a Terrorist Attack: an In-Depth Investigation Into the 1998 Bombings of the U.S

Anatomy of a Terrorist Attack: An in-Depth Investigation Into the 1998 Bombings of the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania 2005-17 About the Matthew B. Ridgway Center The Matthew B. Ridgway Center for International Security Studies at the University of Pittsburgh is dedicated to producing original and impartial analysis that informs policymakers who must confront diverse challenges to international and human security. Center programs address a range of security concerns—from the spread of terrorism and technologies of mass destruction to genocide, failed states, and the abuse of human rights in repressive regimes. The Ridgway Center is affiliated with the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and the University Center for International Studies (UCIS), both at the University of Pittsburgh. This working paper is one of several outcomes of Professor William W. Keller’s “Anatomy of a Terrorist Attack” Capstone course from the spring of 2005. Briefing ii iii Briefing iv Anatomy of a Terrorist Attack An In-Depth Investigation Into The 1998 Bombings of the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania v Briefing vi Credits Project Coordinators Kevin Bernarding Matthew Schuster Lead Editor Becky Champagne Co-Editors Wayne B. Cobb II Sascha Kaplan Don Morrison Secondary Editors Zachary Beus William Strachan Analysts Juliana Bahus, Tanzania Background Zachary Beus, Kenya Background Don Morrison, Kenya Background David Grimes, al Qaeda Background and GIS Specialist Bryan Mazzolini, Chronology, Events of August 7th, 1998, and Conclusions Kevin Bernarding, The Bomb Factory and Executive Summary Joseph Gealy, Embassy Security Sascha Kaplan, Immediate Aftermath Tom Fitzgerald, U.S. Military Response Kate Worley, U.S.