Carpenter Ants: Their Biology and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus Pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption

Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption Colleen A. Cannon Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology Richard D. Fell, Chairman Jeffrey R. Bloomquist Richard E. Keyel Charles Kugler Donald E. Mullins June 12, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: diet, feeding behavior, food, foraging, Formicidae Copyright 1998, Colleen A. Cannon Nutritional Ecology of the Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer): Macronutrient Preference and Particle Consumption Colleen A. Cannon (ABSTRACT) The nutritional ecology of the black carpenter ant, Camponotus pennsylvanicus (De Geer) was investigated by examining macronutrient preference and particle consumption in foraging workers. The crops of foragers collected in the field were analyzed for macronutrient content at two-week intervals through the active season. Choice tests were conducted at similar intervals during the active season to determine preference within and between macronutrient groups. Isolated individuals and small social groups were fed fluorescent microspheres in the laboratory to establish the fate of particles ingested by workers of both castes. Under natural conditions, foragers chiefly collected carbohydrate and nitrogenous material. Carbohydrate predominated in the crop and consisted largely of simple sugars. A small amount of glycogen was present. Carbohydrate levels did not vary with time. Lipid levels in the crop were quite low. The level of nitrogen compounds in the crop was approximately half that of carbohydrate, and exhibited seasonal dependence. Peaks in nitrogen foraging occurred in June and September, months associated with the completion of brood rearing in Camponotus. -

HOUSEHOLD ARTHROPODS Nuisance Household Jean R

2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 OVERVIEW Guidelines & Principles Groups of pests Public health pests HOUSEHOLD ARTHROPODS Nuisance Household Jean R. Natter Structural pests 2015 2 MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES DETERMINE MANAGEMENT Define the problem Eradicate? Damage? Critter(s)? Control? ID the critter Manage? Pest? Tolerate? Dangerous? (people, pets, or structures?) Did it just stumble indoors? Verify: PNW Insect Management Handbook Appropriate management 3 4 CAPTURE THE CRITTER RECOMMENDATIONS Research-based management EPA says: Pest control materials must be labeled for that purpose * * * * * * * * * * (Common Sense Pest Control) No home remedies 5 6 Jean R. Natter 2015 Household Pests 1 2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 PUBLIC HEALTH: BED BUGS 3/16” Broadly flat, oval Cracks, crevices, & PUBLIC HEALTH PESTS seams (naturephoto.cz.com) Eggs glued in place Blood feeders (Bed Bugs; WSU; FS070E) Bites w/o pain Odor: sweet; acrid Bed Bugs (FS070E) 7 (J. R. Natter) 8 MANAGEMENT: BED BUGS PUBLIC HEALTH: MOSQUITOES Key Points Mattress: Encase or heat Rx Launder bedding, clothes – hot! Pest control company (NY Times) (L & R: University of Missouri; gambusia Stamford University) 9 10 MANAGEMENT: MOSQUITOES PUBLIC HEALTH: FLEAS Key Points Adults on animal Eggs drop off Source reduction Larvae ½” Personal protection w/tan head Mosquito fish (Gambusia), if legal Larvae eat debris Rx for larvae: Bti Pupa “waits” (Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis) Nest parasites (University of Illinois) 11 12 Jean R. Natter 2015 Household Pests 2 2015 Household Pests 2/22/2015 MANAGEMENT: FLEAS PUBLIC HEALTH: TICKS Rocky Mountain wood tick Key Points 3-step program Dermacentor species 1. Vacuum often East of Cascades 2. Insect growth regulator (IGR) Immatures feed mostly on carpet & pet’s “nest” on rodents 3. -

Sisters Or Strangers: How Does Relatedness Affect Foraging in Carpenter Ants?

Sisters or strangers: How does relatedness affect foraging in carpenter ants? Lauren Hwang-Finkelman1, Marissa Lopez2, Alondra Murguia3, Nathalie Treminio1 1 University of California, Davis; 2 University of California, Irvine; 3 University of California, Santa Cruz ABSTRACT Optimal foraging theory (OFT) states that animals will forage in a way that maximizes energy intake while minimizing energy expenditure. Eusocial insects are examples of species that exhibit OFT. One type of eusocial insect is the carpenter ant (Camponotus). Carpenter ants use pheromone trails as a form of communication. In using chemical cues to communicate with one another, carpenter ants fulfill OFT by maximizing energy rewards and minimizing energy spent searching for resources. We conducted choice trials with different sugar water concentrations and observed how relatedness between ants affected foraging behavior. We tested if carpenter ants would act according to OFT and forage from the resource with the highest energy reward or if the presence of non-related ants would influence their behavior. We collected ants at Mclaughlin Natural Reserve in California and placed them in an arena with four different sugar water concentrations either with ants of the same colony (sisters; intracolonial) or ants of a different colony (strangers; intercolonial). Our findings supported our hypothesis that the presence of ants from different colonies affects foraging preferences. Intracolonial ants took less time to visit concentrations and made more visits to higher concentrations in comparison to ants in intercolonial trials. We theorize that this may be due to the chemical cues used to distinguish between ants of the same colony and to communicate the presence of sugar water. -

MO-310.2 Urban Integrated Pest Management

CANCELLED 0525LP5423400 FOREWORD Although there are many ways to manage or control pest prob- lems, the use of pesticides is frequently selected. Some of these chemicals are extremely persistent in the environment and toxic by their very nature. Public concerns over their extensive use and their detrimental effects on human health, wildlife re- sources and other environmental components, demand that we provide continuous professional review and training in selection and application of sound control measures. Pesticides are unique because they are purposely released into the environment to affect pest plants or animals and simultaneously may become an environmental contaminant. It is our expertise that not only determines their efficacy, but also minimizes their adverse environmental impact. The objective of pest management is effective control with minimal use of the least toxic product available. The Department of the Navy, a steward of 3.9 million acres of land at some 250 shore installations and landlord to a million people, shall continue to support these concerns. Program emphasis shall be on professional management of installa- tion pest management programs, controlled application by or under the supervision of trained and certified personnel, and use of cost-effective strategies, and use of approved pesticides and equipment. The purpose of this publication is to facilitate training the activity pest controller. Pesticide use is closely regulated under the Federal Insecti- cide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act and several other federal statutes. Navy pesticide applicators, in every case, should consider state or host country requirements in their pest manage- ment operations. Recommendations for improvement are encouraged from any party and these should be furnished to the Commander, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Code 1634, 200 Stovall Street, Alexandria, VA 22332-2300. -

Arthropods of Public Health Significance in California

ARTHROPODS OF PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE IN CALIFORNIA California Department of Public Health Vector Control Technician Certification Training Manual Category C ARTHROPODS OF PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE IN CALIFORNIA Category C: Arthropods A Training Manual for Vector Control Technician’s Certification Examination Administered by the California Department of Health Services Edited by Richard P. Meyer, Ph.D. and Minoo B. Madon M V C A s s o c i a t i o n of C a l i f o r n i a MOSQUITO and VECTOR CONTROL ASSOCIATION of CALIFORNIA 660 J Street, Suite 480, Sacramento, CA 95814 Date of Publication - 2002 This is a publication of the MOSQUITO and VECTOR CONTROL ASSOCIATION of CALIFORNIA For other MVCAC publications or further informaiton, contact: MVCAC 660 J Street, Suite 480 Sacramento, CA 95814 Telephone: (916) 440-0826 Fax: (916) 442-4182 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.mvcac.org Copyright © MVCAC 2002. All rights reserved. ii Arthropods of Public Health Significance CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................ v DIRECTORY OF CONTRIBUTORS.............................................................................................. vii 1 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES ..................................... Bruce F. Eldridge 1 2 FUNDAMENTALS OF ENTOMOLOGY.......................................................... Richard P. Meyer 11 3 COCKROACHES ........................................................................................... -

The Spatial Distribution of Wood-Nesting Ants in the Central

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gary R. Nielsen for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on March 6, 1986. Title: The Spatial Distribution of Wood-Nesting Ants in the Central Coast Range of Oregon / 4 Abstractapproved: Redacted for privacy Fred okickson Two coniferous forests in the central Coast Range of western Oregon were surveyed for nests of wood inhabiting ants.Nineteen species and 825 ant nests were found, corresponding to an average nest density of 0.079 nests/m2 (maximum 0.38/m2) and a mean species density of 0.026 species/m2 (maximum 0.08/m2). The spatial distribution of all species was random within the study areas In contrast, the nest distribution patterns of the six most common species and all ants combined were found to be highly clumped (contagious) due to high nest densities on a few favorable sites. Most ants achieved greatest nest densities on high imsdlatim, early successional plots such as clear- cuts. The nest abundances of 15 species were negatively correlated with tree canopy cover. However, Lasius pallitarsis and Leptothorax nevadensis had higher nest densities in woody debrison forested plots. Furthermore, the nest densities of all ants combined, and of nine individual species were greater in stumps than logs. Within stumps, the nests of all species combined, as well as Camponotus modoc, Tapinoma sessile, and Lasius pallitarsis were concentratedon the south sides of stumps.The bark, cambial zone, and wood of woody debris in all stages of decompositionwere exploited by ants for nest sites. Leptothorax nevadensis, Tapinoma sessile, and Aphaenogaster subterranea occupied bark significantly more often than other tissues. -

Do It Yourself SAFE and EFFECTIVE PEST MANAGEMENT for YOUR HOME, BUSINESS OR SCHOOL Richard

Do It Yourself SAFE AND EFFECTIVE PEST MANAGEMENT FOR YOUR HOME, BUSINESS OR SCHOOL Richard “Bugman” Fagerlund All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. FORWARD Every year, approximately 5.1 billion pounds of pesticides are used in the United States alone. Pesticides are intentionally toxic substances associated with birth defects, mutations, reproductive effects and cancer. Exposing our families to these pesticides makes them especially vulnerable to loss of brain function, damage to their reproductive systems, childhood leukemia, soft tissue sarcoma, neuroblastoma, Wilms' tumor, Ewing's sarcoma, nonHodgkins lymphoma, brain cancer, colorectal cancer and testes cancer. Many "inert" ingredients found in pesticides are suspected carcinogens and have been linked to central nervous system disorders, liver and kidney damage, birth defects and many other serious threats to our health. The warning label on Roundup is 10 pages alone! So why do we continue to use them? Is it possible the loss of brain function associated with pesticide use is what is driving our decision to continue using them? 5.1 billion pounds are being dumped on our gardens, lawns, trees, shrubs, and making their way into our rivers, our water supply, our food supply and our bodies. We are slowly poisoning ourselves and our environment. 96% of all fish analyzed in major rivers and streams contain residues of one or several pesticides. 100% of all surface water contains one or more pesticides. Pesticides, and especially herbicides, are contaminating our water supply. Removal is costly and difficult, and not always 100% effective. Pesticides are suspected to be the cause of amphibian declines and mutations as well as the rapid decline of our most important pollinator, the honey bee. -

A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 11B - Giant Sequoia Literature Review

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 11b - Giant Sequoia Literature Review Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.11b ON THE COVER Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park Photography by: Brent Paull A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 11b - Giant Sequoia Literature Review Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.11b R. Wayne Harrison Senior Environmental Scientist (Ret.) California Department of Parks and Recreation August 29, 2011 [This paper was funded by a grant from the Save the Redwoods League.] June 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This document contains subject matter expert interpretation of the data. -

Carpenter Ants: Their Biology and Control

Extension Bulletin 0818 CARPENTER ANTS: THEIR BIOLOGY AND CONTROL Most carpenter ant species establish their initial nest in decayed wood, but, once established, the ants ex tend their tunneling into sound wood and can do con siderable damage to a structure. However, this damage occurs over 3 or more years, since the in itial colony consists of a single queen. Workers are produced at a slow rate, so that a colony consisting of 200 to 300 workers is at least 2 to 4 years old. Most problems in Washington caused by carpenter ants are due to Camponotus modoc and C. vicinus. These species commonly nest in standing trees (liv ing or dead), in stumps, or in logs on the forest floor. Fig. 1. C. modoc colony. Since many houses are being built in forested areas, well established, vigorous colonies are readily Structural Damage available in the immediate vicinity to attack these dwellings. This is especially true when the Carpenter ants are a problem to humans because of homeowner insists that the home be built with a their habit of nesting in houses (Figs. 1, 2). They minimal removal of trees. do not eat wood, but they remove quantities of it to expand their nesting facilities. This can result in A number of workers from these large "parent" col damage to buildings and, if the main structural beams onies will frequently move into a dwelling as a are hollowed out, can result in an unsafe condition. "satellite" colony of this parent colony. Com- Typical damage is shown in Fig. 3. Fig. -

NESTING and FORAGING CHARACTERISTICS of the BLACK CARPENTER ANT Camponotus Pennsylvanicus Degeer (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE)

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2007 Nesting And Foraging Characteristics Of The lB ack Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Donald Oswalt Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Oswalt, Donald, "Nesting And Foraging Characteristics Of The lB ack Carpenter Ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (2007). All Dissertations. 158. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/158 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NESTING AND FORAGING CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BLACK CARPENTER ANT Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Entomology by Donald A. Oswalt December 2007 Accepted by: Eric P. Benson, Committee Chair Peter H. Adler William C. Bridges, Jr. Patricia A. Zungoli ABSTRACT Potential nesting sites of Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) were investigated in South Carolina to determine if nesting sites features could be characterized by habitat features for black carpenter ant nests. Environmental data from forested plots showed large-scale habitat features such as vegetation density and canopy cover were not useful as indicators for the presence or absence of nests. Small-scale individual nest characteristics such as diameter at breast height of trees, log length, tree defect type or tree species were better indicators of occupied nests. -

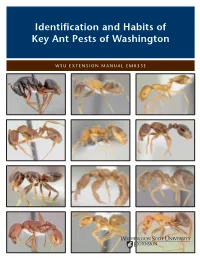

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals. -

( HYNENOPTERA FORMICIDAE ) By

-1— SCENT AND LIGHT ORIENTATION BY FORAGING 4C.1.' ( HYNENOPTERA FORMICIDAE ) by C.T. David, B.Sc.. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London. Imperial College of Science and, Technology, Field Station, • Ashurst Lodge, Ascot, Berkshire. April 1973. -2- ABSTRACT. After a brief description of the laboratory maintenance of the ants and of the design of the foraging arena, the method of testing for a light orientation in a foraging ant is given. Two methods of orientation are described; pottering and menotaxis. The times taken by ants to complete unsuccessful foraging journeys in the arena are given, and these are compared with figures for other species. The method used by the ants to orient towards the nest is discussed theoretically and experimentally. Experiments were performed to discover the factors maintaining menotaxis in ants leaving the nest, and to investigate the factors affecting the angle of this orientation to the light. Ante orient towards food by different mechanisms. These are described and discussed in relation to various theories of klinokinesis. The method of orienting towards the nest by fed ants is examined, and is found to differ from that of unfed ants. A correlation was found between the distances walked before feeding by an ant, and the distance it subsequently walks towards the nest after feeding. The mechanism of this was investigated. Ants lay trails from food sources too large to carry to the nest in one journey. Experiments are described dealing with the existence and lifetime of trails; the sensory cues associated with the presence of more food than can be carried to the nest; the absence of any intrinsic orientation in an odour trail; the method of orientation of ants following odour trails; and the factors influencing the taking up of a menotaxis in trail following ants.