Audio Media in the Service of the Totalitarian State? 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Payment and Settlement Systems of the Bank for International Settlements and the International Organization of Securities Commissions

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation Payment and Settlement PSS Systems Analysis and Statistics No. 41 The National Payment System in 2012 2013 © The Central Bank of the Russian Federation, 2007 107016 Moscow, Neglinnaya St., 12 Prepared by the Bank of Russia National Payment System Department E-mail: [email protected] The survey was prepared for print by the Periodicals Division of the Bank of Russia Press Service The survey is available on the Bank of Russia website at: http://www.cbr.ru THE NATIONAL PAYMENT SYSTEM IN 2012 ANALYSIS AND STATISTICS – No. 41. 2013 Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. PAYMENT SYSTEMS .....................................................................................................9 I.1. Payment systems registered by the Bank of Russia ............................................................10 Box 1. Payment systems’ importance criteria ........................................................10 Box 2. The National Settlement Depository ............................................................12 I.2. The Bank of Russia Payment System ................................................................................19 I.2.1. Functionality and services provided by the Bank of Russia .........................................19 I.2.2. Interaction with the Federal Treasury and other federal executive bodies ....................23 I.2.3. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics of -

ETD Template

The Anniversaries of the October Revolution, 1918-1927: Politics and Imagery by Susan M. Corbesero B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 1985 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1988 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Susan Marie Corbesero It was defended on November 18, 2005 and approved by William J. Chase Seymour Drescher Helena Goscilo Gregor Thum William J. Chase Dissertation Director ii The Anniversary of the October Revolution, 1918-1927: Politics and Imagery Susan M. Corbesero, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation explores the politics and imagery in the anniversary celebrations of the October Revolution in Moscow and Leningrad from 1918 to 1927. Central to Bolshevik efforts to take political and symbolic control of society, these early celebrations not only provided a vehicle for agitation on behalf of the Soviet regime, but also reflected changing popular and official perceptions of the meanings and goals of October. This study argues that politicians, cultural producers, and the urban public contributed to the design and meaning of the political anniversaries, engendering a negotiation of culture between the new Soviet state and its participants. Like the Revolution they sought to commemorate, the October celebrations unleashed and were shaped by both constructive and destructive forces. A combination of variable party and administrative controls, harsh economic realities, competing cultural strategies, and limitations of the existing mass media also influenced the Bolshevik commemorative projects. -

Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920S-1930S

“Soviet Architecture and its National Faces ”: Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920s-1930s By Anna Pronina Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative History Supervisor: Professor Charles Shaw Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2020 Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The thesis “Soviet Architecture and its National Faces”: Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920s-1930s is devoted to the various ways Soviet Central Asian architecture was imagined during the 1920s and the 1930s. Focusing on the discourses produced by different actors: architects, Soviet officials, and restorers, it examines their perception of Central Asia and the goals of Soviet architecture in the region. By taking into account the interdependence of national and architectural history, it shows a shift in perception from the united cultural region to a set of national republics with their own histories and traditions. The thesis proves that national architecture of the Soviet Union, and in Central Asia in particular, was a visible issue in public architectural discussions. Therefore, architecture played a significant role in forging national cultures in Soviet Central Asia. -

The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By

Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By Howard Douglas Allen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair Professor Ann Swidler Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2013 Abstract Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater by Howard Douglas Allen Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair The theater played an essential role in the making of the Soviet system. Its sociological interest not only lies in how it reflected contemporary society and politics: the theater was an integral part of society and politics. As a preeminent institution in the social and cultural life of Moscow, the theater was central to transforming public consciousness from the time of 1905 Revolution. The analysis of a selected set of theatrical premieres from the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 to the end of Cultural Revolution in 1932 examines the values, beliefs, and attitudes that defined Soviet culture and the revolutionary ethos. The stage contributed to creating, reproducing, and transforming the institutions of Soviet power by bearing on contemporary experience. The power of the dramatic theater issued from artistic conventions, the emotional impact of theatrical productions, and the extensive intertextuality between theatrical performances, the press, propaganda, politics, and social life. Reception studies of the theatrical premieres address the complex issue of the spectator’s experience of meaning—and his role in the construction of meaning. -

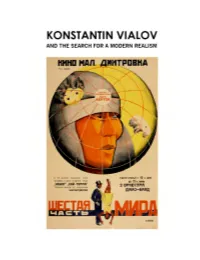

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Soviet Music in the International Arena, 1932–41

02_EHQ 31/2 articles 26/2/01 12:57 pm Page 231 Caroline Brooke Soviet Music in the International Arena, 1932–41 Soviet musical life underwent radical transformation in the 1930s as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union began to play an active role in shaping artistic affairs. The year 1932 saw the dis- banding of militant factional organizations such as the RAPM (Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians) which had sprung up on the ‘musical front’ during the 1920s and had come to dominate Soviet musical life during the period of the first Five Year Plan (1928–32). 1932 was also the year that saw the con- solidation of all members of the musical profession into centralized Unions of Soviet Composers. Despite such compre- hensive administrative restructuring, however, it would be a mis- take to regard the 1930s as an era of steadily increasing political control over Soviet music. This was a period of considerable diversity in Soviet musical life, and insofar as a coherent Party line on music existed at all at this time, it lacked consistency on a great many issues. One of the principal reasons for the contra- dictory nature of Soviet music policy in the 1930s was the fact that the conflicting demands of ideological prejudice and politi- cal pragmatism frequently could not be reconciled. This can be illustrated particularly clearly through a consideration of the interactions between music and the realm of foreign affairs. Soviet foreign policy in the musical sphere tended to hover between two stools. Suspicion of the bourgeois capitalist West, together with the conviction that Western culture was going through the final stages of degeneration, fuelled the arguments of those who wanted to keep Soviet music and musical life pure and uncontaminated by such Western pollutants as atonalism, neo- classicism and the more innovative forms of jazz. -

The Soviet Union Today

AN OUTLINE STUDY 94?. 08+ A512^H THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES THE SOVIET UNION TODAY An Outline Study Syllabus and Bibliography by The Staff of THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE 56 WEST 45th STREET, NEW YORK, 19, N. Y. NEW YORK, 1943 Copyright 1943 by THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, INC. 56 West 45th Street New York, 19, N. Y. Prepared by the Staff of The American Russian Institute: BERNARD L. KOTEN WILLIAM MANDEL JAMES P. MITCHELL HARRIET L. MOORE ROSE N. RUBIN Edited and Produced under union conditions; composed, printed and bound by union labor. BMU - UOPWA 18 CIO <*gi^*.@ ABCO PRESS INC * TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword (7) Purpose, Division of Time, Study Kit, Readings, Suggested Methods of Use (7). Chapter I. The Land and the People (8-15) Map of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, (8-9). I. Area and Population of the Sixteen Republics (9). II. The Peoples (10-12) ; Slavic (10), Turkic and Turco — Tatar (11), Transcaucasian (11), Iranian (11), Baltic (11), Finno-Ugrian (11), Mongol (11), Armenian (11), Jewish (11), German (11), Molda- vian (12), of the North (12). III. Physical Geography and Climate (12-15); Range (12), Vegetation (12), Economic Geography of European Russia (13), of the Urals (13), of Siberia (13), of the Far East (13), of the Caucasus (14), of Kazakhstan (14), of Central Asia (14), of the Arctic (15). Discussion Questions (15). Chapter II. The Historical Setting (16-23) Study Suggestions (16). I. Background for the Overthrow of Tsarism (16-17), the February Revolution (16). -

Totalitarian Communication

Kirill Postoutenko (ed.) Totalitarian Communication Kirill Postoutenko (ed.) Totalitarian Communication. Hierarchies, Codes and Messages Gedruckt mit der Unterstützung des Deutschen Historischen Institut (Moskau) und des Exzellenzclusters 16 ›Kulturelle Grunlagen von Integration‹ (Universität Konstanz) Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deut- sche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2010 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or repro- duced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopy- ing and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Proofread by Kirill Postoutenko Typeset by Nils Meise Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-8376-1393-3 Distributed in North America by Transaction Publishers Tel.: (732) 445-2280 Rutgers University Fax: (732) 445-3138 35 Berrue Circle for orders (U.S. only): Piscataway, NJ 08854 toll free 888-999-6778 CONTENTS Acknowledgments 9 Prolegomena to the Study of Totalitarian Communication KIRILL POSTOUTENKO 11 HIERAR CHIES Stalinist Rule and its Communication Practices An Overview LORENZ ERREN 43 Public Communication in Totalitarian, Authoritarian and Statist Regimes A Comparative Glance -

Celebrating Suprematism: New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir

Celebrating Suprematism Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks (The Johns Hopkins University) Christina Lodder (University of Kent) Volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Celebrating Suprematism New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich Edited by Christina Lodder Cover illustration: Installation photograph of Kazimir Malevich’s display of Suprematist Paintings at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, 0.10 (Zero-Ten), in Petrograd, 19 December 1915 – 19 January 1916. Photograph private collection. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lodder, Christina, 1948- editor. Title: Celebrating Suprematism : new approaches to the art of Kazimir Malevich / edited by Christina Lodder. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2019] | Series: Russian history and culture, ISSN1877-7791 ; Volume 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN2018037205 (print) | LCCN2018046303 (ebook) | ISBN9789004384989 (E-book) | ISBN 9789004384873 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich, 1878-1935–Criticism and interpretation. | Suprematism in art. | UNOVIS (Group) Classification: LCCN6999.M34 (ebook) | LCCN6999.M34C452019 (print) | DDC 700.92–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037205 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN1877-7791 ISBN 978-90-04-38487-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-38498-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Russian Art of the Avant-Garde

Russian Art of the Avant-Garde THE DOCUMENTS OF 20TH-CENTURY ART ROBERT MOTHERWELL, General Editor BERNARD KARPEL, Documentary Editor ARTHUR A. COHEN Managing Editor Russian Art of the Avant-Garde Theory and Criticism 1902-1934 Edited and Translated by John E. Bowlt Printed in U.S.A. Acknowledgments: Harvard University Press and Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd.: "Realistic Manifesto" from Gabo by Naum Gabo. Copyright © 1957 by Lund Humphries. Reprinted by permission. Thames and Hudson Ltd.: "Suprematism in World Reconstruction, 1920" by El Lissitsky. This collection of published statements by Russian artists and critics is in- tended to fill a considerable gap in our general knowledge of the ideas and theories peculiar to modernist Russian art, particularly within the context of painting. Although monographs that present the general chronological framework of the Russian avant-garde are available, most observers have comparatively little idea of the principal theoretical intentions of such move- ments as symbolism, neoprimitivism, rayonism, and constructivism. In gen- eral, the aim of this volume is to present an account of the Russian avant- garde by artists themselves in as lucid and as balanced a way as possible. While most of the essays of Vasilii Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich have already been translated into English, the statements of Mikhail Larionov, Natalya Goncharova, and such little-known but vital figures as Vladimir Markov and Aleksandr Shevchenko have remained inaccessible to the wider public either in Russian or in English. A similar situation has prevailed with regard to the Revolutionary period, when such eminent critics and artists as Anatolii Lunacharsky, Nikolai Punin, and David Shterenberg were in the forefront of artistic ideas. -

JUNE 2020. 30 NEW ACQUISITIONS: Fight Against Fascism, Health Education, Literature, Art F O R E W O R D

JUNE 2020. 30 NEW ACQUISITIONS: Fight Against Fascism, Health Education, Literature, Art F O R E W O R D Dear friends, Our last catalogue was presented at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in early March. The world seems to be a different place now. While all of our book shops remained closed during the lockdown, we continued to work hard and were focusing on the things that made the most sense during these difficult times - the books. When preparing this catalogue, we have found out that the books and their subjects sometimes begin to reflect what is happening in the world right now, in a way reminding us what is truly important. We were planning to open the catalogue with the collection of items printed during the WWII in Russia and dedicate it to the 75th anniversary of the victory over fascism, and sadly some of the books are still relevant now, including the item #1 in the catalogue - Clara Zetkin’s warning against fascism from 1921. The second section of the catalogue is dedicated to the health education of the masses in Soviet Union of the 1920s, the time when the foundations of the strong Soviet medical system were laid. Item #6 includes the info and photographs of how to treat patients at home, the edition also offers photographic explanation on how to disinfect which seems relevant today. In the same group of books several early Soviet scientific texts are presented, including the research of Ivan Pavlov on hysteria (#9). After cataloging all of the above it was nice to return to our usual interests such as art, cinema, theatre, literature, travel, etc.