Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920S-1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art Presents: Ugo Rondinone Your Age and My Age and the Age of the Rainbow Garage Square Commissions

GARAGE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART PRESENTS: UGO RONDINONE YOUR AGE AND MY AGE AND THE AGE OF THE RAINBOW GARAGE SQUARE COMMISSIONS March 10–May 21, 2017 Garage Museum of Contemporary Art presents a new work by Ugo Rondinone (b. 1964 in Brunnen, Switzerland, lives in New York), specifically created for Garage Square Commissions. The artist’s first project in Russia will consist of two interconnected pieces: an installation in front of the Museum, and an object on its rooftop. In Garage Square, visitors will find a one- hundred-meter-long fence supporting thousands of images of rainbows painted on wood panels by kids with various disabilities from all over the country. Garage Rooftop will also be host to a ten- meter long rainbow that spells out OUR MAGIC HOUR. This message celebrates the inauguration of the first Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, which is taking place simultaneously inside the Museum. Having emerged in Rondinone's work in 1997, first as a sculpture for a public space, the rainbow has since become one of his most recognizable images, a convergence of visual and poetic energies—according to the artist, each rainbow represents a complete work of poetry. When Rondinone made site visits to Moscow, he determined that public engagement would be one of the key aspects of the new work, as well as wanting to produce something that was responsive to the context of Garage. Acknowledging the Museum’s interest in developing country wide networks, he asked that his project should be far-reaching. Assisted by Garage’s Inclusive Program department, the artist engaged 1,500 children, including deaf and hard of hearing kids, as well as children in wheelchairs and with developmental disabilities, in nine cities across Russia: Moscow, St. -

DOM Magazine No

2020 DOM magazine 04 December The Art of Books and Buildings The Cities of Tomorrow Streets were suddenly empty, and people began to flee to the countryside. The corona virus pandemic has forced us to re- think urban design, which is at the heart of this issue. From the hotly debated subject of density to London’s innovative social housing through to Berlin’s creative spaces: what will the cities of the future look like? See pages 14 to 27 PORTRAIT The setting was as elegant as one would expect from a dig- Jean-Philippe Hugron, nified French institution. In late September, the Académie Architecture Critic d’Architecture – founded in 1841, though its roots go back to pre- revolutionary France – presented its awards for this year. The Frenchman has loved buildings since The ceremony took place in the institution’s rooms next to the childhood – the taller, the better. Which Place des Vosges, the oldest of the five ‘royal squares’ of Paris, is why he lives in Paris’s skyscraper dis- situated in the heart of the French capital. The award winners trict and is intrigued by Monaco. Now he included DOM publishers-author Jean-Philippe Hugron, who has received an award from the Académie was honoured for his publications. The 38-year-old critic writes d’Architecture for his writing. for prestigious French magazines such as Architecture d’au jourd’hui and Exé as well as the German Baumeister. Text: Björn Rosen Hugron lives ten kilometres west of the Place des Vosges – and architecturally in a completely different world. -

View. Theories and Practices Ofvisual Culture

9 View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture. title: tMitolen:umentality ephemerated author: aNuintahoSro(s:na source: Vsoieuwrc. eT:heories and Practices ofVisual Culture 9 (2015) URL: hURttLp: ://pismowidok.org/index.php/one/article/view/275/533/ publisher: Ipnusbtiltiushteero:f Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences Institute of Polish Culture, University of Warsaw View. Foundation for Visual Culture Nina Sosna Monumentality ephemerated Monuments, which are generally considered visual, become the object of visual research much less frequently than any other art form. However, closer investigation shows that monuments are an interesting model or even frame of analysis. They are quite peculiar, and paradoxical objects, as they controversially combine many different kinds of things: the immaterial traits of collective imaginaries and the heavy materiality of stone or bronze, fluctuations of memory and the conservation of ideology, object and remnant, arrested past and an attempt to change the future. 1. Russia is currently going through a period of instability that is caused, not only by today's situation of an almost uncontrolled globalized world economy, but also by the transitional form of (post)socialism. There is a temporal factor that affects the very structure of the status quo. What is undergoing a noticeable change are not only the From: Yevgeniya Gershkovich, Yevgeny external conditions of existence, but also the sense of Korneev, eds., Stalin’s Imperial Style time. The “dashing 1990s” were a time to move forward - (Moscow: Trefoil Press, 2006), photo: at least, such was the general feeling. In the 2000s there Krzysztof Pijarski was a kind of break; for some, it was a moment of “looking around” and even backwards. -

Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde

87T" ACSA ANNUAL MEETING 125 Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde ELIZABETH C. ENGLISH University of Pennsylvania THE CONTEXT OF THE DEBATES BETWEEN Gogol and Nikolai Nadezhdin looked for ways for architecture to THE WESTERNIZERS AND THE SLAVOPHILES achieve unity out of diverse elements, such that it expressed the character of the nation and the spirit of its people (nnrodnost'). In the teaching of Modernism in architecture schools in the West, the Theories of art became inseparably linked to the hotly-debated historical canon has tended to ignore the influence ofprerevolutionary socio-political issues of nationalism, ethnicity and class in Russia. Russian culture on Soviet avant-garde architecture in favor of a "The history of any nation's architecture is tied in the closest manner heroic-reductionist perspective which attributes Russian theories to to the history of their own philosophy," wrote Mikhail Bykovskii, the reworking of western European precedents. In their written and Nikolai Dmitriev propounded Russia's equivalent of Laugier's manifestos, didn't the avantgarde artists and architects acknowledge primitive hut theory based on the izba, the Russian peasant's log hut. the influence of Italian Futurism and French Cubism? Imbued with Such writers as Apollinari Krasovskii, Pave1 Salmanovich and "revolutionary" fervor, hadn't they publicly rejected both the bour- Nikolai Sultanov called for "the transformation. of the useful into geois values of their predecessors and their own bourgeois pasts? the beautiful" in ways which could serve as a vehicle for social Until recently, such writings have beenacceptedlargelyat face value progress as well as satisfy a society's "spiritual requirements".' by Western architectural historians and theorists. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Spring Newsletter

Spring 2019 iwcmoscow.ru Newsletter 1 1 Int ernat ional Wom en's Club of Moscow iw cm oscow.ru TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Letter from the Pr esident 04 Concer t for Char ity 08 Inter national Women's Evening 10 On the Cover : Tsar itsyno 12 In Memor y: Connie Meyer 13 IWC Char ities Fund 16 Coffee Mor nings 17 Inter est Group Spotlight 18 Meet & Gr eet 22 IWC on Social Media 23 Contacts 2 2 Letter from the Pr esident Dear and lovely m em bers of our Club, We are coming to the end of a busy year, where we met many new, interesting people, who then became very close to us. Our Club gives us the chance to learn about new cultures and opens up new horizons. In the past year, IWC held two very successful and large-scale events to raise funds for charities. As you know, these events were the Winter Bazaar and the Charity Concert. In 2018-2019, we supported over 25 charity projects. You can find a listing of the projects along with a description of the ways in which we helped this year on pages 14-15. On the eve of summer, let me wish you all a good holiday and unforgettable new memories. Thank you for being with us. We are working to continue to make progress and trying to make you happy with new and interesting events. Love and appreciation to all of you! Sincerely, Mery Toganyan President of the International Women's Club Spouse of the Armenian Ambassador to the Russian Federation 3 3 Concer t for Char ity On Monday, May 20, the International Women's Club of Moscow together with the Association of Winners of the International Tchaikovsky Competition presented a Charity Concert dedicated to the 40th anniversary of the Club. -

Modernist Frontiers

PRESS RELEASE Modernist Frontiers – Then and now Avantgarde Kommunikation mbH is pleased to announce that its EXPO 2017 cooperation partner Garage will host the international architectural conference at EXPO 2017 | 22 – 23 July (Munich/Astana, 19 July 2017) On the occasion of the EXPO 2017 in Kazakhstan, this weekend the two- day international conference will take place at the Astana Contemporary Art Center. Initiated by Garage, the conference has been called to provide a context for discussion on Almaty’s modernist architecture (1960s–1980s), presenting it to the international expert community and launching a conservation campaign for this extremely important part of the former Kazakh capital’s architectural history. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow and the Parisian museum Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais are cooperation partners of the international creative agency Avantgarde, which was commissioned with execution and overall coordination for the Astana Contemporary Art Center (ACAC). In an effort to bring together different points of view and create an interdisciplinary environment for the study of modernist architecture in Almaty, researchers from a range of countries and different academic communities will speak at the conference. It will present various views on both the history of postwar modernist architecture and on contemporary problems in the restoration of such architecture and its adaptation to new functions. The program The first day of the conference, “The Regional Specifics of Soviet Modernism,” will set the historical and theoretical context for the discussion of Soviet architectural heritage in the former republics of the USSR. The first session will contrast shared aspects of Soviet heritage with regionally unique traits in the architecture of the former Soviet republics. -

How to Preserve an Experiment? Soviet Avant-Gardearchitecture 1917-1933;

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING AND PRESERVATION Fall semester 2014 How to Preserve an Experiment? Soviet Avant-GardeArchitecture 1917-1933; Prof. Xenia Vytuleva Email: [email protected] Fridays, 9.00am - 11.00 am 300 SBuell Hall Office hours by appointment only Description This graduate seminar considers the phenomenon of the Soviet Architectural Avant- Garde as part of a broader cultural history. The response of artistic thought to the machine, as well as the intersection of political and social propaganda, literature, art and cinematography will be examined. Special attention will be paid to the legacy of the experimental practices, such as paper architecture, oral history, temporary projects for International Exhibitions, law, geography, material and visual culture, cultural anthropology, stage design,and the projects for National Competitions. It is a cross- disciplinary class: focused on Avant-garde artistic discourse with the emphasis onhow to preserve architecture as politically and ideologically charged media.It creates a "manifesto map" of conceptual categories: negative histories and conflict zones, re- performance, propaganda and palimpsest, the politics of camouflage and concealment, reassembling identities and performing utopia. In addition to classroom lectures and discussion, students will engage with current exhibitions, archival materials, films, primary documents and objects at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMa),as well as at the Rare Book Collection, Columbia University. 1 Course Format: Weekly lectures provide the framework of the course. The Powerpoint for each lecture will be made available on Blackboard. A portion of some class will be devoted to discussion of the power of preservation as political science and rethinking the current stage of a discipline. -

Dialogue of the Seas No.5, 2012

Black Sea-Caspian Sea: strategy for a wider region Cultural heritage and barbarians of the XXIst century No. 5, 2012 BSEC’s th 0anniversary: Alexander 2mutual trust, Dugin: common priorities formula Azerbaijan and Europe’s to the future energy security of Eurasia It’s raining with Olympic medals VlaDE DivaC: THE LEGEND GOES ON SERBIA LOOKS IN TOMORROW BorodinoBorodino Panorama Panorama The Adriatic landscape - the background of the “summit” of the Black Sea-Caspian Sea Fund BSCSIFCHRONICLE - is the direct proof of the Fund’s broadening BSCSIFCHRONICLE PHOTO: VYacheslav SAMOSHKIN outward the region The “Maestral” Hotel will be remembered as the place where important decisions were made impersonated by the Ambassador Livio Hürzeler - joining our ranks. This suggests that the values targeted by the statute and the strategy of the Fund, and, foremost, the promotion LE of dialogue, peace and harmony, are in tune with the European ones, but also in tune with the Eurasian values, because we also accepted an Iranian IC citizen as a full BSCSIF member. Today, our Fund is getting wider, indeed. Where did our meeting take place? At the Adriatic Sea, in Mon- tenegro, and this is not a part of the Black Sea- Caspian Sea region. The Assembly’s attendees paid a moment-of-silence According to the second pivotal tribute to the tragically deceased friend - BSCSIF Vice- decision adopted, there will be estab- President, Prof. Tamaz Beradze A strategy lished within the Fund a Center for Strategic Research of the Black Sea – Caspian Sea region. It was a very wise idea - to gather under one roof for a wider region scholars, professionals and academi- cians from most of our countries. -

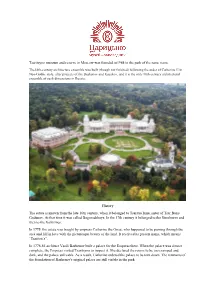

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

Audio Media in the Service of the Totalitarian State? 2010

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Dmitri Zakharine Audio Media in the Service of the Totalitarian State? 2010 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12405 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Zakharine, Dmitri: Audio Media in the Service of the Totalitarian State?. In: Kirill Postoutenko (Hg.): Totalitarian Communication – Hierarchies, Codes and Messages. Bielefeld: transcript 2010, S. 157– 176. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12405. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839413937.157 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Audio Media in the Service of the Totalitarian State? DMITRI ZAKHARINE State Totalitarianism or Media Totalitarianism? The question concerning the logical relationship between the structures and media of totalitarianism has been treated controversially in contem- porary scholarship. A large part of the relevant publications (represented by Hannah Arendt and Leonard Schapiro)1 defines totalitarian power primarily as the power of a charismatic leader over the unwilling major- ity and, following Aristotle’s concept of tyranny, sees the latter as rooted in structures of political order.2 A second corpus of research increas- ingly interprets totalitarianism as technological power and associates 1 | See: Hannah Arendt (1951: 465): “[. ] totalitarian government in its initial stages must behave like a tyranny and raze the boundaries of man-made law”.