„Regained Territories” of Poland After the World War II in the Light of Their Letters to Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Administration and Security Studies 2018 Nr 5

Studia Administracji i Bezpieczeństwa Public Administration and Security Studies 2018 nr 5 Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii im. Jakuba z Paradyża w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim Gorzów Wielkopolski 2018 Honorowy patronat – Rektor Akademii im. Jakuba z Paradyża prof. dr hab. Elżbieta Skorupska ‑Raczyńska Redakcja prof. dr hab. Bogusław Jagusiak (redaktor naczelny), dr Anna Chabasińska (zastępca redaktora naczelnego), mgr Joanna Lubimow (sekretarz) Rada naukowa Członkowie: Członkowie goście: prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Czachór prof. Veysel Dinler prof. dr hab. Janusz Faryś prof. dr hab. Franciszek Gołembski prof. dr hab. Grzegorz Kucharczyk prof. Cristina Hermida del Llano prof. AJP dr hab. Paweł Leszczyński prof. dr hab. Ryszard Ławniczak prof. AJP dr hab. Jerzy Rossa prof. dr hab. Piotr Mickiewicz dr hab. prof. nadzw. Joachim von Wedel prof. Olegas Prentkovskis dr Jacek Jaśkiewicz prof. Miruna Tudorascu dr Robert Maciejczyk prof. dr hab. Wołodymar Welykoczyj dr Katarzyna Samulska prof. dr hab. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz dr Aleksandra Szczerba‑Zawada prof. dr hab. Marek Żmigrodzki dr Andrzej Skwarski dr hab. prof. UG Tadeusz Dmochowski dr Piotr Lizakowski dr hab. prof. WAT Adam Kołodziejczyk dr hab. prof. WAT Piotr Kwiatkiewicz dr hab. prof. UG Jarosław Nicoń dr hab. inż. prof. WAT Gabriel Nowacki dr hab. inż. prof. WAT Janusz Rybiński prof. nadzw. UŁ dr hab. Tomasz Tulejski dr hab. prof. WAT Jerzy Zalewski dr hab. Marek Ilnicki kmdr. dr hab. Grzegorz Krasnodębski kmdr. dr hab. Jarosław Teska Recenzent dr hab. Jerzy Stańczyk dr hab. Tomasz Kamiński Korekta językowa: Joanna Rychter Skład: Agata Libelt Projekt okładki: Jacek Lauda © Copyright by Akademia im. Jakuba z Paradyża w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim 2018 Redakcja informuje, że pierwotną wersją czasopisma jest wydanie papierowe. -

Generate PDF Z Tej Stronie

Volhynia Massacre https://volhyniamassacre.eu/zw2/history/174,Chronology.html 2021-09-27, 15:40 Chronology 1941/1942 — Ukrainians in Volhynia begin to form military detachments, partly for protection against the pacifications conducted by German units with the use of Ukrainian police. Birth of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Ukrayins’ka Povstans’ka Armiya, UPA) led by the prewar Petlura- supporter Taras Bulba-Borovets. Spring/summer 1943 — Taras Bulba-Borovets is attacked for his refusal to submit to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Bandera faction (Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv, OUN-B) and to participate in the ongoing anti-Polish ethnic cleansings. Late 1942 — the conference of miltary officials of Bandera’s OUN in Lvov results in a decision to form partisan detachments that are to initiate a nationwide uprising at the most opportune moment. Moreover, all Poles and Jews are to be expelled from Ukrainian territory under threat of death. Those who refuse to leave voluntarily are to be killed. 1942/1943 — Bandera’s OUN forms partisan detachments in Volhynia. They begin to use a name that was to become widely known in Volhynia — the UPA. February 9, 1943 — a UPA detachment under the command of Hryhorij Perehijniak “Dovbesho-Korobko” massacres the Polish village of Parośle, killing over 150 people. March/April 1943 — about 5,000 Ukrainian policemen, ones who have participated in the extermination of Jews, desert from the German service and join the pro-Bandera partisan units. March and April 1943 — the greatest intensification of the UPA’s massacres, committed mostly in Sarny, Kostopol, and Krzemieniec counties. March 1943 — UPA detachments under the command of Ivan Lytvynchuk “Dubovy” massacre a minimum of 179 people in Lipniki. -

1 a Polish American's Christmas in Poland

POLISH AMERICAN JOURNAL • DECEMBER 2013 www.polamjournal.com 1 DECEMBER 2013 • VOL. 102, NO. 12 $2.00 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY SUPERMODEL ESTABLISHED 1911 www.polamjournal.com JOANNA KRUPA JOURNAL VISITS DAR SERCA DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE PAGE 12 RORATY — AN ANCIENT POLISH CUSTOM IN HONOR OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN • MUSHROOM PICKING, ANYONE? MEMORIES OF CHRISTMAS 1970 • A KASHUB CHRISTMAS • NPR’S “WAIT, WAIT … ” APOLOGIZES FOR POLISH JOKE CHRISTMAS CAKES AND COOKIES • BELINSKY AND FIDRYCH: GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN • DNA AND YOUR GENEALOGY NEWSMARK AMERICAN SOLDIER HONORED BY POLAND. On Nov., 12, Staff Sergeant Michael H. Ollis of Staten Island, was posthumously honored with the “Afghanistan Star” awarded by the President of the Republic of Poland and Dr. Thaddeus Gromada “Army Gold Medal” awarded by Poland’s Minister of De- fense, for his heroic and selfl ess actions in the line of duty. on Christmas among The ceremony took place at the Consulate General of the Polish Highlanders the Republic of Poland in New York. Ryszard Schnepf, Ambassador of the Republic of Po- r. Thaddeus Gromada is professor land to the United States and Brigadier General Jarosław emeritus of history at New Jersey City Universi- Stróżyk, Poland’s Defense, Military, Naval and Air Atta- ty, and former executive director and president ché, presented the decorations to the family of Ollis, who of the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of DAmerica in New York. He earned his master’s and shielded Polish offi cer, Second lieutenant Karol Cierpica, from a suicide bomber in Afghanistan. -

ADMINISTRACYJNO-PRAWNE the OPOLE STUDIES in ADMINISTRATION and LAW Kwartalnikl Quarterly Czerwiecl June 2020

OPOLSKIE STUDIA ADMINISTRACYJNO-PRAWNE THE OPOLE STUDIES IN ADMINISTRATION AND LAW Kwartalnikl Quarterly Czerwiecl June 2020 Zeszytl Issue 2 UNIWERSYTET OPOLSKIl UNIVERSITY OF OPOLE ISSN 1731-8297 http://osap.wpia.uni.opole.pl e-ISSN 6969-9696 SCIENTIFIC BOARD / RADA NAUKOWA Andrzej Bator (University of Wrocław) Silvestre Bello Rodríguez (Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria) Tadeusz Bojarski (Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin) Maria del Carmen Lázaro Guillamón (Universitat „Jaume I” Castellón de la Plana) Stanisław Hoc (University of Opole) LotharKnopp (Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg) Wojciech Kowalski (University of Silesia) WłodzimierzKuryło (Academy of Sciences of Higher Education in Kiev) VasilicaNegrut (Danubius University of Galati) Tomasz Sokołowski (Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań) Jerzy Zajadło (University of Gdańsk) José Luis Zamora Manzano (Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria) EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / REDAKTOR NACZELNY Włodzimierz Kaczorowski THEMATIC EDITORS / REDAKTORZY TEMATYCZNI Stefan Marek Grochalski–European law EwaKozerska – Sciences of History and political-legal doctrines Przemysław Malinowski, Marta Woźniak – public law Piotr Stec –private law SECRETARY / SEKRETARZ REDAKCJI Marta Woźniak ADDRESS OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD / ADRES REDAKCJI Wydział Prawa i Administracji Uniwersytetu Opolskiego ul. Katowicka 87a 45-060 Opole e-mail: [email protected] Declaration concerning the original version The Editorial Board declare that the original (referential) version of the Journal is available in the paper form. http://prawo.uni.opole.pl/studia.php CONTENTS ARTICLES Rafał ADAMUS, Legally protected cultural goods and bankruptcy proceedings . 9 Wojciech CYRUL, Tomasz PEŁECH-PILICHOWSKI, Legislating in hypertext . 27 Joanna CZAPLIŃSKA, “It was an awful mistake with that girl. Advise me what to do.” On Jaroslav Hašek’s bigamy . -

Morris, Adelaide

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Faculty of Arts Ti ricordo questo uomo? : A creative and critical investigation into crossing cultures, countries, and identities Adelaide Morris ORCID orcid.org/0000-0002-5250-1945 Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publicly available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0hq1924k Author Zelechowski, Jamie Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Germanic Languages by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski 2017 © Copyright by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski Doctor of Philosophy in Germanic Languages University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Todd S. Presner, Co-Chair Professor Roman Koropeckyj, Co-Chair My dissertation investigates the cinematic representation of forced migration (due to the border changes enacted by the Yalta and Potsdam conferences in 1945) in East Germany, West Germany, and Poland, from 1945–1970. My thesis is that, while the representations of these forced migrations appear infrequently in feature film during this period, they not only exist, but perform an important function in the establishment of foundational national narratives in the audiovisual sphere. Rather than declare the existence of some sort of visual taboo, I determine, firstly, why these images appear infrequently; secondly, how and to what purpose(s) existing representations are mobilized; and, thirdly, their relationship to popular and official discourses. -

Early Testimonies of Jewish Survivors of World War II

Tragedy and Triumph Early Testimonies of Jewish Survivors of World War II Compiled and Translated by Freda Hodge ABOUT THIS BOOK In this collection Freda Hodge retrieves early voices of Holocaust survivors. Men, women and children relate experiences of deportation and ghetto isation, forced labour camps and death camps, death marches and liber ation. Such eyewitness accounts collected in the immediate postwar period constitute, as the historian Feliks Tych points out, the most important body of Jewish documents pertaining to the history of the Holocaust. The fresh ness of memory makes these early voices profoundly different from, and historically more significant than, later recollections gathered in oral history programs. Carefully selected and painstakingly translated, these survivor accounts were first published between 1946 and 1948 in the Yiddish journal Fun Letzten Khurben (‘From the Last Destruction’) in postwar Germany, by refugees waiting in ‘Displaced Persons’ camps, in the American zone of occupation, for the arrival of travel documents and visas. These accounts have not previously been available in English. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Freda Hodge holds degrees in English, Linguistics and Jewish Studies, and has taught at universities and colleges in South Africa and Australia. Fluent in Hebrew as well as Yiddish, she works at the Holocaust Centre in Melbourne conducting interviews with survivors and families. Copyright Information Tragedy and Triumph: Early Testimonies of Jewish Survivors of World War II Compiled and translated by Freda Hodge © Copyright 2018 All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. -

The Book of the Righteous of the Eastern Borderlands 1939−1945

THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 About the Ukrainians who rescued Poles subjected to extermination by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army Edited by Romuald Niedzielko THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 About the Ukrainians who rescued Poles subjected to extermination by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army Edited by Romuald Niedzielko Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation Graphic design Krzysztof Findziński Translation by Jerzy Giebułtowski Front cover photograph: Ukrainian and Polish inhabitants of the Twerdynie village in Volhynia. In the summer of 1943 some local Ukrainians were murdering their Polish neigh- bors while other Ukrainians provided help to the oppressed. Vasyl Klishchuk – one of the perpetrators, second from the right in the top row. Stanisława Dzikowska – lying on ground in a white scarf, one of the victims, murdered on July 12, 1943 with her parents and brothers (photo made available by Józef Dzikowski – Stanisława’s brother; reprinted with the consent of Władysław and Ewa Siemaszko from their book Ludobójstwo dokonane przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich na ludności polskiej Wołynia 1939–1945, vol. 1–2 [Warsaw, 2000]) Copyright by Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ISBN 978-83-7629-461-2 Visit our website at www.ipn.gov.pl/en and our online bookstore at www.ipn.poczytaj.pl. CONTENTS Introduction . 7 1 Volhynia Voivodeship . 23 2 Polesie Voivodeship . -

Issues of Land Reform and Poland's Post-War Borders in The

Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej ■ LI-SI(2) Adrian Karolak MBP Łódź-Widzew Issues of land reform and Poland’s post-war borders in the broadcasts of Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station Outline of contents: Between 1941 and 1942, one general radio station, and 16 secret for- eign-language (national) stations operated from Soviet territory; among them was the Polish- -language Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station, which began operations in August 1941, and functioned until 22 August 1944. According to the broadcasters, the land reform should consist in expropriating the owners of large landholdings, and distributing their possessions among peasants and farm labourers. As regards the Poland’s future borders, the broadcasters presented the position of their political superiors, according to whom the eastern voivodeships of the Polish Republic should be transferred to the Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian Soviet Republics. Keywords: Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station, Communist International (Comintern), Polish communists, Polish post-war borders, land reform During its three-year existence, the Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station addressed many subjects relevant to Polish citizens who found themselves under German occupation. Among the key issues discussed, two merit special attention: the land reform and Poland’s post-war borders. The main idea behind the planned socio-economic changes was, according to the Polish left, the need to cut ties with a bygone reality, strange to the “simple” man (peasants and workers). This can be concluded from the station’s broadcasts. Their authors claimed that the relations of property prevailing in the Polish countryside in the interwar period were incompatible with the needs of the peasants. -

PZH 19 Dodruk

Piotrkowskie Zeszyty Historyczne, t. 19 (2018), z. 1 Katarzyna Kaczmarek (Instytut Historii Uniwersytetu Opolskiego) Do szkoły nie poszedłem, bo wybuchła wojna . Zapis autobiograficzny mieszkańca Kresów Wschodnich Tadeusza Słobodziana W niniejszym opracowaniu została podjęta próba ukazania sytu- acji dzieci podczas II wojny światowej na terenie wsi Zniesienie 1. Jako zasadniczy materiał źródłowy została wykorzystana relacja 2 Tadeusza Słobodziana 3. Dla uzupełnienia materiału źródłowego odwołano się także do relacji osobistej innych mieszkańców tej wsi i jej okolic. W tym względzie cenne są wspomnienia Wojciecha Pleszczaka 4. Wybuch wojny zmienił życie mieszkańców II Rzeczypospolitej. Okupację radziecką oraz niemiecką cechowały represje, prześladowa- nia, czystki etniczne dokonane przez oddziały Ukraińskiej Powstań- czej Armii (UPA), aresztowania, wywózki oraz deportacje ludności cywilnej. W niniejszym artykule przedstawiona została sytuacja dzieci podczas wojny przez pryzmat wspomnień jednego z nich – Tadeusza Słobodziana. Zniesienie położone było pośród lasów i pól Tarnopolszczyzny w uzdrowiskowej kotlinie leśnej, kilometr od rzeki Seret 5. Wieś liczyła około 454 mieszkańców, w tym narodowości polskiej były 423 osoby, ukraińskiej – 31. Łącznie 114 rodzin: 107 polskich i 7 ukraińskich. Większość mieszkańców utrzymywała się z małych skrawków własnej ziemi i z sezonowej pracy na folwarku, w lesie, w kamieniołomie, jak również u bogatszych sąsiadów. Na terenie Zniesienia znajdował się jeden mały murowany kościół, niewielki sklep spożywczy, -

Україна Європа Світ Ukraine Europe World

УКРАЇНА ЄВРОПА СВІТ UKRAINE EUROPE WORLD Міжнародний збірник наукових праць Серія: Історія, міжнародні відносини The International Collection of Scientific Works Series: History, International Relations Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University UKRAINE EUROPE WORLD The International Collection of Scientific Works Series: History, International Relations Founded in 2008 Issue 22 Ternopil – 2019 Міністерство освіти і науки України Тернопільський національний педагогічний університет імені Володимира Гнатюка УКРАЇНА ЄВРОПА СВІТ Міжнародний збірник наукових праць Серія: Історія, міжнародні відносини Заснований 2008 р. Випуск 22 Тернопіль – 2019 Ukraine–Europe–World. The International Collection of Scientific Works. Series: History, International Relations / Editor-in-chief L. M. Alexiyevets. – Is. 22. – Ternopil: Publishing House of Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, 2019. – 180 p. Approved to be published by the Scientific Council of Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, Record of proceedings № 13 (June 25, 2019). Editorial Advisory Board: Yu. M. Alexeyev, Doctor of History, Professor, Kyiv Slavic University, L. M. Alexiyevets, Doctor of History, Professor, Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University (editor-in- chief), M. M. Alexiyevets, Doctor of History, Professor, Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, V. Balyuk, Doctor (habilitated) of Political Science, Professor, M. Kyuri- Sklodovska University in Lublin, Polish Republic, M. V. Barmak, Doctor of History, Professor, Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, V. Bonusyak, Doctor (habilitated) of History, Professor, Zheshov University, Polish Republic, B. B. Buyak, Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, S. V. Vidnyanskyi, Doctor of History, Professor, Institute of History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NAS of Ukraine), Yu. -

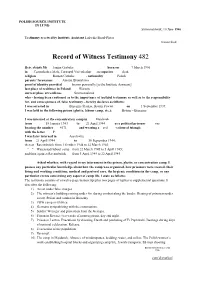

Record of Witness Testimony 482

POLISH SOURCE INSTITUTE IN LUND Strömsnäsbruk, 10 June 1946 Testimony received by Institute Assistant Ludwika Broel-Plater transcribed Record of Witness Testimony 482 Here stands Ms Janina Grabska born on 7 March 1906 in Czarnokońce Małe, Tarnopol Voivodeship , occupation clerk religion Roman Catholic , nationality Polish parents’ forenames Antoni, Bronisława proof of identity provided known personally [to the Institute Assistant] last place of residence in Poland Warsaw current place of residence Strömsnäsbruk who – having been cautioned as to the importance of truthful testimony as well as to the responsibility for, and consequences of, false testimony – hereby declares as follows: I was arrested in Brzeziny Śląskie, Bytom Powiat on 1 September 1939. I was held in the following prison (ghetto, labour camp, etc.): Bytom – Brzeziny. I was interned at the concentration camp in Majdanek from 18 January 1943 to 21 April 1944 as a political prisoner yes bearing the number 4571 and wearing a red -coloured triangle with the letter P. I was later interned in Auschwitz from 21 April 1944 to 30 September 1944; then at Ravensbrück from 1 October 1944 to 22 March 1945; ″ ″ Watenstedt labour camp from 22 March 1945 to 5 April 1945; and then again at Ravensbrück from 5 April 1945 to 22 April 1945. Asked whether, with regard to my internment in the prison, ghetto, or concentration camp, I possess any particular knowledge about how the camp was organized, how prisoners were treated, their living and working conditions, medical and pastoral care, the hygienic conditions in the camp, or any particular events concerning any aspect of camp life, I state as follows: The testimony consists of a twelve-page manuscript plus two pages of replies to supplemental questions.