Tuning Modernity: Musical Knowledge and Subjectivities in Colonial India, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor: Issues of Violence and Social Justice

Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor: Issues of Violence and Social Justice Research Briefs with Policy Implications Published by: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group GC-45, Sector-III, First Floor Salt Lake City Kolkata-700106 India Web: http://www.mcrg.ac.in Printed by: Graphic Image New Market, New Complex, West Block 2nd Floor, Room No. 115, Kolkata-87 The publication is a part of the project 'Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor'. We thank all the researchers, discussants and others who participated in the project and in the project related events. We also thank the MCRG team for their support. The support of the Ford Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Content Introduction 1 Part One: Research Briefs Section I: Kolkata 5 • Taking Refuge in the City: Migrant Population and Urban Management in Post-Partition Calcutta by Kaustubh Mani Sengupta • Urban Planning, Settlement Practices and Issues of Justice in Contemporary Kolkata by Iman Kumar Mitra • Migrant Workers and Informality in Contemporary Kolkata by Iman Kumar Mitra • A Study of Women and Children Migrants in Calcutta by Debarati Bagchi and Sabir Ahmed • Migration and Care-giving in Kolkata in the Age of Globalization by Madhurilata Basu Section II: Delhi 25 • The Capital City: Discursive Dissonance of Law and Policy by Amit Prakash • Terra Firma of Sovereignty: Land, Acquisition and Making of Migrant Labour by Mithilesh Kumar • ‘Transient’ forms of Work and Lives of Migrant Workers in ‘Service’ Villages of Delhi by Ishita Dey Section III: Mumbai 35 • Homeless Migrants -

A BETTER WAY to BUILD DEMOCRACY Instructor: Doug Mcgetchin, Ph.D

Non-Violent Power in Action A BETTER WAY TO BUILD DEMOCRACY Instructor: Doug McGetchin, Ph.D. Stopping the deportation of Jewish spouses in Nazi Berlin, the liberation of India, fighting for Civil Rights in the U.S., the fall of the Berlin Wall, the ouster of Serbia’s Milosevic and the recent Arab Awakening, all have come about through non-violent means. Most people are unaware of non-violent power, as the use of force gains much greater attention in the press. This lecture explains the effectiveness of non-violent resistance by examining multiple cases of nonviolence struggle with the aim of understanding the principles that led to their success. Using these tools, you can help create a more peaceful and democratic world. Thursday, April 20 • 9:45 –11:15 am $25/member; $35/non-member Doug McGetchin, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of History at Florida Atlantic University where he specializes in the history of the international connections between modern Germany and South Asia. He is the author of “Indology, Indomania, Orientalism: Ancient India’s Rebirth in Modern Germany” (2009) and several edited volumes (2004, 2014) on German-Indian connections. He has presented papers at academic conferences in North America, Europe, and India, including the German Studies Association, the World History Association and the International Conference of Asian Scholars (Berlin). He is a recipient of a Nehru- Fulbright senior research grant to Kolkata (Calcutta), India and a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) grant to Leipzig, Germany, and has won multiple teaching awards. FOR MORE INFORMATION: Call 561-799-8547 or email [email protected] 5353 Parkside Drive, PA – 134, Jupiter, FL 33458 | www.fau.edu/llsjupiter. -

Wilson Brought out a New Edition of Mill's History of British India, in Which He Footnoted What He Thought to Be Mill's Errors

HORACE HAYMAN WILSON AND GAMESMANSHIP IN INDOLOGY NATALIE P. R. SIRKIN SHORTLY AFTER THE DEATH OF JAMES MILL) HORACE HAYMAN Wilson brought out a new edition of Mill's History of British India, In which he footnoted what he thought to be Mill's errors. Review ing these events in a recent survey of nineteenth-century Indian historians, Professor C. H. Philips comments: It is incredible that he should not have chosen to write a new history altogether, but possibly his training as a Sanskritist, which had accustomed him to the method of interpreting a text in this way, had something to do with his choice.' But why? Professor Philips might as well have asked why he did not write his own books on Hindoo law and on Muslim law instead of bringing out a new edition of Macnaghten; or why he did not collect his own proverbs, instead of editing the Hindoostanee and Persian proverbs of Captain Roebuck and Dr. Hunter; or why he did not write his own book on travels in the Himalayas, instead of editing Moorcroft's; or why he did not write his own book on Sankhya philosophy, instead of editing H. T. Colebrooke's : or why he hid not write his own book 011 archaeology in Afghanistan, instead of using Masson's materials.. To suggest Mr. Wilson might have written his OWll History of British India is to suggest that' he was a scholar and that he was interested in the subject. As to the latter, he never wrote again on the subject. As to the former, his education had not prepared him for it, Educated (as the Dictionary of National Biography reports) "in Soho Square," he then .apprenticed himself in a London .hos pital and proceeded to Calcutta as a surgeon for the East India Company. -

John Benjamins Publishing Company Historiographia Linguistica 41:2/3 (2014), 375–379

Founders of Western Indology: August Wilhelm von Schlegel and Henry Thomas Colebrooke in correspondence 1820–1837. By Rosane Rocher & Ludo Rocher. (= Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 84.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013, xv + 205 pp. ISBN 978-3-447-06878-9. €48 (PB). Reviewed by Leonid Kulikov (Universiteit Gent) The present volume contains more than fifty letters written by two great scholars active in the first decades of western Indology, the German philologist and linguist August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1767–1789) and the British Indologist Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765–1837). It can be considered, in a sense, as a sequel (or, rather, as an epistolary appendix) to the monograph dedicated to H. T. Colebrooke that was published by the editors one year before (Rocher & Rocher 2012). The value of this epistolary heritage left by the two great scholars for the his- tory of humanities is made clear by the editors, who explain in their Introduction (p. 1): The ways in which these two men, dissimilar in personal circumstances and pro- fessions, temperament and education, as well as in focus and goals, consulted with one another illuminate the conditions and challenges that presided over the founding of western Indology as a scholarly discipline and as a part of a program of education. The book opens with a short Preface that delineates the aim of this publica- tion and provides necessary information about the archival sources. An extensive Introduction (1–21) offers short biographies of the two scholars, focusing, in particular, on the rise of their interest in classical Indian studies. The authors show that, quite amazingly, in spite of their very different biographical and educational backgrounds (Colebrooke never attended school and universi- ty in Europe, learning Sanskrit from traditional Indian scholars, while Schlegel obtained classical university education), both of them shared an inexhaustible interest in classical India, which arose, for both of them, due to quite fortuitous circumstances. -

4.10.2013 > 26.01.2014 PRESS CONFERENCE a Preliminary Outline of the Programme 6 November 2012

4.10.2013 > 26.01.2014 PRESS CONFERENCE A preliminary outline of the programme 6 November 2012 - Palais d’Egmont, Brussels www.europalia.eu 1 PRACTICAL INFORMATION PRESS Inge De Keyser [email protected] T. +32 (0)2.504.91.35 High resolution images can be downloaded from our website www.europalia.eu – under the heading press. No password is needed. You will also find europalia.india on the following social media: www.facebook.com/Europalia www.youtube.com/user/EuropaliaFestival www.flickr.com/photos/europalia/ You can also subscribe to the Europalia- newsletter via our website www.europalia.eu Europalia International aisbl Galerie Ravenstein 4 – 1000 Brussels Info: +32 (0)2.504.91.20 www.europalia.eu 2 WHY INDIA AS GUEST COUNTRY? For its 2013 edition, Europalia has invited India. Europalia has already presented the rich culture of other BRIC countries in previous festivals: europalia.russia in 2005, europalia.china in 2009 and europalia.brasil in 2011. Europalia.india comes as a logical sequel. India has become an important player in today’s globalised world. Spontaneously India is associated with powerful economical driving force. The Indian economy is very attractive and witnesses an explosion of foreign investments. But India is also a great cultural power. The largest democracy in the world is a unique mosaic of peoples, languages, religions and ancient traditions; resulting from 5000 years of history. India is a land of contrasts. A young republic with a modern, liberal economy but also a land with an enormous historical wealth: the dazzling Taj Mahal, the maharajas, beautiful temples and palaces and countless stories to inspire our imagination. -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

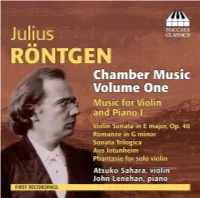

Toccata Classics TOCC0024 Notes

P JULIUS RÖNTGEN, CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME ONE – WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO I by Malcolm MacDonald Considering his prominence in the development of Dutch concert music, and that he was considered by many of his most distinguished contemporaries to possess a compositional talent bordering on genius, the neglect that enveloped the huge output of Julius Röntgen for nearly seventy years after his death seems well-nigh inexplicable, or explicable only to the kind of aesthetic view that had heard of him as stylistically conservative, and equated conservatism as uninteresting and therefore not worth investigating. The recent revival of interest in his works has revealed a much more complex picture, which may be further filled in by the contents of the present CD. A distant relative of the physicist Conrad Röntgen,1 the discoverer of X-rays, Röntgen was born in 1855 into a highly musical family in Leipzig, a city with a musical tradition that stretched back to J. S. Bach himself in the first half of the eighteenth century, and that had been a byword for musical excellence and eminence, both in performance and training, since Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatoire in the 1830s and ’40s. Röntgen’s violinist father Engelbert, originally from Deventer in the Netherlands, was a member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and its concert-master from 1873. Julius’ German mother was the pianist Pauline Klengel, sister of the composer Julius Klengel (father of the cellist-composer of the same name), who became his nephew’s principal tutor; the whole family belonged to the circle around the composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg and his wife Elisabet, whose twin passions were the revival of works by Bach and the music of their close friend Johannes Brahms. -

A NOTE from Johnstone-Music

A NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or saved on your computer. These presentations can be downloaded directly. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for Johnstone-Music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles (and neither too the writers with their generous contributions); however, we ask that the name of Johnstone-Music be mentioned if any document is reproduced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable!) comment visit the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you! SPECIAL FEATURE on JOHN FOULDS .. Birth: 2nd November 1880 - Hulme, Manchester, England Death: 25th April 1939 - Delhi, India .. .. Born into a musical family, Foulds learnt piano and cello from a young age, playing the latter in the Hallé Orchestra from 1990 with his father, who was a bassoonist in the same orchestra. He was also a member of Promenade and Theatre bands. .. Simultaneously with cello career he was an important composer of theatre music. Notable works for our instrument included a cello concerto and a cello sonata. Suffering a setback after the decline in popularity of his World Requiem (1919–1921), he left London for Paris in 1927, and eventually travelled to India in 1935 where, among other things, he collected folk music, composed pieces for traditional Indian instrument ensembles, and worked as Director of European Music for All-India Radio in Delhi. -

4) Book Reviews

Prajnan, Vol. XLIX, No. 4, 2020-21 © 2020-21, NIBM, Pune Book Reviews An Economist's Miscellany: From the Groves of Academe to the Slopes of Raisina Hill Kaushik Basu New Delhi, Oxford University Press, March 2020, pp. xxi + 332, Rs. 995 Reviewed by Prof Sanjay Basu, Faculty, National Institute of Bank Management, Pune. In his introduction to Prof. Sukhamoy Chakravarty's Writings on Development, Rakshit (1997) outlines three necessary qualities for a front ranking development economist. These are: (1) An analytical ability of a very high order (2) A Deep Knowledge of Political, Economic and Social History of Nations and (3) A keen perception of problems pertaining to both formulation of policies and their successful implementation. In addition to all these traits, this delectable anthology contains a fourth attribute – Sense of Humour. For instance, the description of a tourist guide's speech as a public good (p. 50) reminds me of quiz competitions, at which I often picked up the right answers to esoteric questions from auditorium chatter – hall collection, in our parlance. A small joke simplifies a difficult concept and the discussion flows on like a stream. Indeed, on this substantive evidence, the author deserves the moniker Tusitala (teller of tales), a là Robert Louise Stevenson, whose burial ground he visited in Samoa. An Economist's Miscellany: From the Groves of Academe to the Slopes of Raisina Hill is a collection of eighty essays in newspapers and magazines, by Prof. Kaushik Basu, between 2005 and 2019. It covers a wide range of topics – inequality, market reforms, authoritarianism, policy perspectives, travelogues, scepticism, personal reminiscences and hobbies. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration.