Viennese Piano Technique of the 1820S and Implications for Today's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

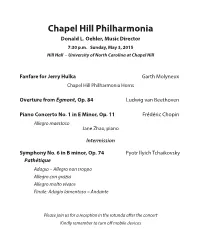

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

HUMMEL Mozart’S Symphonies Nos

HUMMEL Mozart’s Symphonies Nos. 38 ‘Prague’, 39 and 40 Arranged for Flute, Violin, Cello and Piano Uwe Grodd • Friedemann Eichhorn Martin Rummel • Roland Krüger Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) his privy council, after acceding to the throne in 1775, was pirated copies of his original manuscripts were always a Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) that of poet, artist and politician Johann Wolfgang von threat. Hummel was suspicious of editions published on the Goethe. The court theatre immediately became the central continent. In a letter to a friend he wrote: “How come … Mozartʼs Symphonies Nos. 38 ʻPragueʼ, 39 and 40 focus of city life and the addition of the new Hoftheater in you do not find a single note from an honourable German arranged by Hummel for flute, violin, cello and piano 1791 ensured the predominance of music. Hummelʼs publisher?” The editions for this recording were made using dedication of his arrangement of the Prague Symphony Hummelʼs English publications from Chappell and Co In 1786, at the age of eight, Hummel went to live and study aus dem Serail. Hummelʼs lack of diplomacy, however, reads “This Symphony is respectfully dedicated to His (1823-4) for which J. R. Schultz acted as intermediary in with Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in Vienna. During his two combined with his disregard of dress codes, “loud and Excellency Baron von Goethe, Minister of State to His London. While England and France had regulations years as a lodger in the familyʼs apartment in the pushy” manner and devotion to his own performing career Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Saxe Weimar by J. -

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’S Op

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Op. 94 for Viola and Orchestra A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2018 by Fan Yang B. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2008 M. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2010 D. M. A. Candidacy, University of Cincinnati, 2013 Abstract The Potpourri for Viola and Orchestra, Op. 94 by Johann Nepomuk Hummel is available in a heavily abridged edition, entitled Fantasy, which causes confusions and problems. To clarify this misperception and help performers choose between the two versions, this document identifies the timeline and sources that exist for Hummel’s Op. 94 and compares the two versions of this work, focusing on material from the Potpourri missing in the Fantasy, to determine in what ways it contributes to the original work. In addition, by examining historical definitions and composed examples of the genre as well as philosophical ideas about the faithfulness to a work—namely, idea of the early nineteenth-century work concept, Werktreue—as well as counter arguments, this research aims to rationalize the choice to perform the Fantasy or Potpourri according to varied situations and purposes, or even to suggest adopting or adapting the Potpourri into a new version. Consequently, a final goal is to spur a reconsideration of the potpourri genre, and encourage performers and audiences alike to include it in their learning and programming. -

Copyright by Denise Parr-Scanlin 2005

Copyright by Denise Parr-Scanlin 2005 The Treatise Committee for Denise Parr-Scanlin Certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: Beethoven as Pianist: A View Through the Early Chamber Music Committee: K.M. Knittel, Supervisor Anton Nel, Co-Supervisor Nancy Garrett Robert Mollenauer David Neumeyer David Renner Beethoven as Pianist: A View Through the Early Chamber Music by Denise Parr-Scanlin, B.M., M.F.A. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my mother and first piano teacher, Daisy Elizabeth Liles Parr Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the kind assistance of my treatise committee, Dr. Kay Knittel, Dr. Anton Nel, Professor Nancy Garrett, Dr. Robert Mollenauer, Dr. David Neumeyer, and Professor David Renner. I especially thank Dr. Kay Knittel for her expert guidance throughout the project. I also thank Janet Lanier for her assistance with the music examples and my husband, Paul Scanlin, for his constant support and encouragement v Beethoven as Pianist: A View Through the Early Chamber Music Publication No._____________ Denise Parr-Scanlin, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2005 Supervisors: K.M. Knittel, Anton Nel Our inability to reconstruct what Ludwig van Beethoven must have sounded like as a pianist is one of the more vexing questions of music history. Unreliable sources and his short performing career, in addition to a lack of virtuoso public pieces, have contributed to this situation. -

LOUIS SPOHR and the METRONOME a Contribution to Early Nineteenth-Century Performance Practice

LOUIS SPOHR AND THE METRONOME A contribution to early nineteenth-century performance practice by I)r. Martin WulfhorstO This article was previously published in Henryk Wieniawski: Composer and Virtuoso in the Musical Culture of the XIX and XX Centuries, ed. Maciej Jabloriski and Danuta Jasiislra, Poznai: Rltytmos, 2001, pp. i,89-205, ISBN $-9A8462-6-8. N 1763 James Watt developedthe steam engine, in1767 James Hargreaves constructed the spinning jenny and in 1768 Richard Arkwright introduced the spinning frame (Devms 1997: page 680, see bibliography below). Machines triggered a transformation of all economic and social structures that proved more radical than was ever believed possible and it was only natr,ral that musicians too showed a keen interest in various mechanical devices. The Viennese mechanic Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (1772-1838), for instance, invented a Panharmonikon, for which Beethoven composed Wellingtons Sieg oder Die Schlacht bei Vittoria Op.91in 1813 (ANoN. 1813a). But whereas such attempts to replace human per{ormers with machines were shortlived, another mechanical device invented at about the same time and associated with the name of Maelzel has exerted a profound impact on performances to the present day - the metronome. The success of the mechanical metronome stemmed from the fact that its invention coincided with the advent of the modern aesthetics of mwical interpretation, which subordinated the performance to the composition, left fewer and fewer aspects of the composition to the discretion of the player, singer or conductor, and led composers to search for new methods and tools to speci$ their intentions as clearly and precisely as possible. -

Ghost Trio, As Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Op

Reiselust Werke von Beethoven, Spohr und Mendelssohn Eldering Ensemble Reiselust Werke von Beethoven, Spohr und Mendelssohn Eldering Ensemble Simon Monger Violine Jeanette Gier Violoncello Sandra Urba Klavier Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Trio für Klavier, Violine und Violoncello Nr. 5 D-Dur op. 70 Nr. 1 Geistertrio (1808) 01 I. Allegro vivace e con brio .......................................(09'57) 02 II. Largo assai ed espressivo ......................................(10'04) 03 III. Presto .......................................................(07'56) Louis Spohr (1784–1859) Duetto für Pianoforte und Violine op. 96 Reisesonate Nachklänge einer Reise nach Dresden und in die Sächsische Schweiz (1836) 04 I. Reiselust: Allegro ..............................................(08'11) 05 II. Reise: Scherzo ................................................(06'01) 06 III. Katholische Kirche: Andante maestoso – Larghetto ............(06'00) 07 IV. Sächsische Schweiz: Rondo Allegretto .........................(05'59) Weltersteinspielung der neuen Urtextausgabe (Uta Pape), Edition Dohr Köln Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) Trio für Violine, Violoncello und Klavier Nr. 2 c-Moll op. 66 (1845) 08 I. Allegro energico e con fuoco ....................................(10'14) 09 II. Andante espressivo ...........................................(07'02) 10 III. Scherzo. Molto allegro quasi presto ...........................(03'28) 11 IV. Finale. Allegro appassionato ..................................(07'15) Gesamtspielzeit ........................................................(82'15) -

A Master's Recital in Piano

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2013 A master's recital in piano Brittany K. Lensing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2013 Brittany K. Lensing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lensing, Brittany K., "A master's recital in piano" (2013). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 127. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/127 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTER’S RECITAL IN PIANO An Abstract of a Recital Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Brittany K. Lensing University of Northern Iowa December 2013 This Study by: Brittany K. Lensing Entitled: A MASTER’S RECITAL IN PIANO has been approved as meeting the thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Music ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Dmitri Vorobiev, Chair, Thesis Committee ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Theresa Camilli, Thesis Committee Member ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Professor Sean Botkin, Thesis Committee Member ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Michael J. Licari, Dean, Graduate College RECITAL APPROVAL FORM This Recital Performance By: Brittany K. Lensing Entitled: A MASTER’S RECITAL IN PIANO Date of Recital: September 20, 2013 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel Piano Concerto Op

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (b. Bratislava, 14. November 1778 – d. Weimar, 17. Oktober 1837) Piano Concerto op.113 (1827) Beethoven’s VIP friend: Johann Nepomuk Hummel and his fifth Piano Concerto, op. 113 (1827) If there is one composer among Beethoven’s contemporaries that deserves to be better known and has – rightfully – received growing interest from performers and musicologists, then it is certainly Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Eight years Beethoven’s junior (born in 1778), Hummel was a child prodigy, he studied piano with Mozart and lived with the Mozart family for two years. He later succeeded Haydn as a Kapellmeister in Esterházy, and was the dedicatee of Schubert’s three last piano sonatas (D 958-960, 1828). He befriended Goethe and Beethoven, was a pall-bearer at the latter’s funeral, and played at his memorial concert. Indeed, there is no lack of celebrities and Very Important Composers in Hummel’s biography. More importantly, Hummel was a Very Important Pianist himself, boasting a reputation as one of the finest and most influential piano virtuosos of his generation. By the time he composed his Fifth Piano Concerto in 1827, the year of Beethoven’s death, Hummel was a firmly established authority as a piano virtuoso, teacher, and composer. Following Kapellmeister functions in Esterhazy (1804-11) and Stuttgart (1816-18), he was appointed at Weimar in 1819 and was to remain there until his death in 1837. His solid reputation was underpinned by his extensive touring career as a pianist and conductor, and by the publication of his own piano method, the Ausführlich theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano-forte Spiel (Extensive theoretical and practical method of playing the pianoforte, 1828), an impressive tome of more than 450 pages dedicated to the Russian Emperor Nicolas I.