"A Performer's View: Libraries in My Life" in "Music Librarianship in America, Part 4: Music Librarians and Performance"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 68, 1948-1949

W fl'r. r^S^ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON ^r /^:> ,Q 'iiil .A'^ ^VTSOv H SIXTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1948-1949 Carnegie Hall, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra [Sixty-eighth Season, 1948-1949] SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond Allard Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Ralph Masters Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Roll and Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga Emil Kornsand Boaz Piller George Zazofsky George Humphrey Horns Paul Cherkassky Louis Arti^res Harry Dubbs Charles Van Wynbergen Willem Valkenier James Stagliano Vladimir ResnikofiE Hans Werner Principals Joseph Leibovici Jerome Lipson Harry Shapiro Siegfried Gerhardt Einar Hansen Harold Meek Daniel Eisler Violoncellos Paul Keaney Norman Carol Walter Macdonald Carlos P infield Samuel Mayes Osbourne McConathy Alfred Zighera Paul Fedorovsky Harry Dickson Jacobus Langendoen Trumpets Mischa Nieland Minot Beale Georges Mager Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Voisin Karl Zeise Clarence Knudson Prijicipals Pierre Mayer Josef Zimbler Marcel La fosse Manuel Zung Bernard Parronchi Harry Herforth Samuel Diamond Enrico Fabrizio Ren^ Voisin Leon MarjoUet Victor Manusevitch Trombones James Nagy Flutes Jacob Raichman Leon Gorodetzky Georges Laurent Lucien Hansotte Raphael Del Sordo James Pappoutsakis John Coffey Melvin Bryant Phillip Kaplan Josef Orosz John Murray Lloyd Stonestreet Piccolo Tuba Henri Erkelens George Madsen -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

13CPS Coeds Vie Fbr Miss Taicoma Tffcti . K'ii•I

r . tfFcTi . k'ii•i ii 114 LI4T 11 I I Eastman, Carmichael Comeau Also Victorious A record turnout went to the polls Thursday and Fri. lay and found themselves a new president in Dick Water- man. Waterman, a junior from Seattle. received 329 votes, in one of the closest races on the ballot. His opponent, Ran- (ly Smith, trailed with 284. paired up in final elections, Deg- Assisting Waterman in h I s man defeating Miss Royall for the presidential duties next year will sophomore representative past be Howie Eastman, junior from last year. Renton. Eastman became first Next year's sophomore class vice president by polling 323 representative will be Gail Po- votes, while his opponent, Toni kela, freshman from Fede'al Beardemphi gathered 271. Way. Miss Pokefa defeated In the race for second vice Dave Purchase by receiving president, Chuck Comeau came 358 votes to his 241. out on top by receiving 332 All five proposed amendments votes. Comeau, a junior ' from to the constitution passed by an Mercer Island, defeated Ken overwhelming margin. McGill, who received 269 votes. Proposition one, called for au The executive secretary post amendment to the ASCPS Con- went to Jackie Carmichael, junior stitution providing for the ap- from Nanimo, B. C. Miss Car- pointment of an election commit- michael had 318 votes while her tee by the ASCPS President at opponent, Carol Weeks, had 275. the beginning of his term of of- In the May Queen contest, fice, and outlining the organize- Linda Sticklin, senior from tion and duties of that committee. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

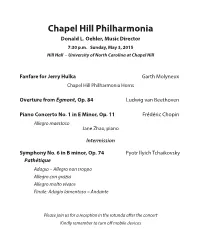

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 67, 1947-1948, Subscription

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SIXTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1947-1948 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1948, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Lewis Perry N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager 1281 [ ] © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © Only © © © © © © you can © © © © © © decide © © © © © © © © © © © Whether your property is large or small, it rep- © © resents the security for your family's future. Its ulti- © © © © mate disposition is a matter of vital concern to those © © you love. © © © © To assist you in considering that future, the Shaw- © © mut Bank has a booklet: "Should I Make a Will?" © © It outlines facts that everyone with property should © © © © know, and explains the many services provided by © © this Bank as Executor and Trustee. © © © © Call at any of our 2 J convenient 'offices, write or telephone © © for our booklet: "Should I Make a Will?" © © © © © © © © © The V^tional © © © © © Shawmut Bank © © 40 Water Street^ Boston © © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © © Capital $10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © "Outstanding Strength"for 112 Years © © [ 1282 ] ! SYMPHONIANA Can you score 1 The "Missa Solemnis" 00? Peabody Award for Broadcasts Honor to Chaliapin New England Opera Theatre Finale FASHION THE 'MISSA SOLEMNIS" QUIZ Instead of trying to describe the mighty Mass in D major, to be per- 1. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1993

a«apB««t6«ii«giiiflmaii! iiaH«:^aatta«li'i|iaHpsjili«2liii«iw;ilo^ .^ 7oo/i ofExcellence '- 4? In every discipline, ,% '*% outstanding performance springs ?•*{. from the combination of skill, A^^^'" <^^ vision and commitment. t.%^ As a technology leader, GE Plastics is dedicated to the development of advanced materials: <k engineering thermoplastics, silicones, superabrasives and circuit board substrates. Like the lively arts that thrive in this inspiring environment, we enrich life's quality through creative excellence. GE Plastics Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Eleventh Season, 1992-93 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President J. Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B.Arnold, Jr. Nina L. Doggett R. Willis Leith, Jr. Peter A. Brooke Dean Freed Mrs. August R. Meyer James F. Cleary Avram J. Goldberg Molly Beals Millman John F. Cogan,Jr. Thelma E. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman Julian Cohen Julian T. Houston Peter C. Read William F. Connell Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Richard A. Smith William M. Crozier, Jr. Allen Z. Kluchman Ray Stata Deborah B. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Archie G. Epps Irving W. Rabb Philip K.Allen Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Allen G. Barry Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George Lee Sargent I>eo L. Beranek Mrs. George I. Kaplan Sidney Stoneman Mrs. John M. Bradley Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Abram T Gollier Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John L. Thorndike Nelson J. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries.