Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’S Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2014-2015

23 Season 2014-2015 Wednesday, January 28, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 30, at 2:00 Saturday, January 31, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Kirill Gerstein Piano Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 I. Allegro con brio II. Andante con moto III. Allegro— IV. Allegro Intermission Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 102 I. Allegro II. Andante III. Allegro Shostakovich/from Suite from The Gadfly, Op. 97a: arr. Atovmyan I. Overture: Moderato con moto III. People’s Holiday: [Allegro vivace] VII. Prelude: Andantino XI. Scene: Moderato This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The January 28 concert is sponsored by MEDCOMP. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us immediately following the January 30 concert for a Chamber Postlude, featuring members of The Philadelphia Orchestra. Brahms Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60 I. Allegro non troppo II. Scherzo: Allegro III. Andante IV. Finale: Allegro lomodo Mark Livshits Piano Kimberly Fisher Violin Kirsten Johnson Viola John Koen Cello 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Mozart-Rezeption in Franz Danzis Der Berggeist1 Adrian Kuhl

»Feingefühlte Charakteristik« Mozart-Rezeption in Franz Danzis Der Berggeist1 Adrian Kuhl I In der Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung erschien am 25. März 1804 ein Artikel über Wolfgang Amadeus Mozarts Opern, in dem der anonyme Autor über Charakteristika von dessen Musiktheater reflektiert: Was aber den meisten Menschen entgeht, ist die feingefühlte Charakteristik, nicht allein der einzelnen Personen, sondern der ganzen Handlung einer jeden Oper. Im Don Juan die Mischung von Erhabenheit und Leichtsinn; im Figaro die joviale Haltung des Ganzen; in der Zauberflöte Munterkeit gepaart mit Würde und feyerlichem Ernste; in Così fan tutte die sanften Halbtinten der feinern Welt- verhältnisse, diese süsse Schwärmerey, die von der Ouvertüre bis zum letzten Ak- kord des Schlusschors das schönste, in allen Theilen harmonischste Ganze ausma- chen, das irgend ein Künstler je hervorzubringen vermochte, in der Entführung aus dem Serail diese Nationalcharakteristik in der erhabensten Darstellung – was überhaupt ein Vorzug Mozart’s, und nur bey ihm in der Grösse anzutreffen ist: diese Einheit des Charakters – wer hat das je gefühlt, bemerkt, bewundert? Wenn aber ein jedes seiner theatralischen Werke das grosse, seltene Verdienst der Einheit und Charakteristik, das Gepräge des feinsten Menschenkenners an der Stirne trägt: welchem soll ich den Vorzug geben?2 1 Der folgende Beitrag basiert auf Teilen meines Vortrags bei der Tagung Mozartvariationen. Franz Danzi und die Mozartverehrung im ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert, die am 15. Juni 2013 anlässlich des 250. Geburtstages des Komponisten von der Forschungsstelle »Geschichte der Südwestdeutschen Hofmusik im 18. Jahrhundert« der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissen- schaften in Schwetzingen ausgerichtet wurde. 2 [Franz Danzi]: »An meinen Freund«, in: Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 6 (1804), No. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

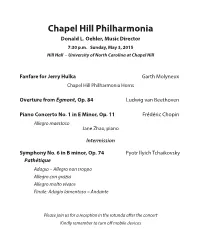

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

Was Schön, Was Herrlich Heißen Kann ...«

»... alles, was schön, was herrlich heißen kann ...« Kammermusikkonzert »Kleine Serenade« Im Rahmen des Themenjahres 2020 »Unendlich schön. Monumente für die Ewigkeit« Schlossgarten Schwetzingen am Minervatempel 19 Uhr, 26. August 2020 PROGRAMM CARLO GIUSEPPE TOESCHI (1731–1788) Flötenquartett in C-Dur aus: Six simphonies ou quatuors dialogués, Paris [ca. 1764] Allegro grazioso – Menuetto FERDINAND FRÄNZL (1767–1833) Flötenquartett in D-Dur aus: Deux Quatuors [...] op. 10, Augsburg [ca. 1810] Allegro – Andante – Allegretto FRANZ DANZI (1763-1826) Flötenquartett in d-Moll aus: Trois Quatuors […] op. 56, Offenbach (1819) Allegretto – Andantino – Allegretto Menuetto – Allegretto Manches schöne Bauwerk überdauert seine Zeit und wird von der Nachwelt immer noch bewundert. Carl Theodor von der Pfalz hat sich nicht nur mithilfe der Bau- oder Kunstwerke Denkmäler errichten lassen, sondern ging als Begründer der berühmten kurpfälzischen Hofkapelle in die Musikgeschichte ein. Die Virtuosen und Komponisten seiner Hofmusik waren europaweit bekannt und leisteten gewichtige Beiträge vornehmlich auf dem Gebiet der Instrumentalmusik. Ihre Sinfonien und Konzerte hätte man mit einem antiken Minerva- oder Apollo-Tempel vergleichen können. Selbst in kleineren Dimensionen wie in den Werken für kammermusikalische Besetzungen waren sie mitunter federführend. Als die Quartettbesetzung mit einer Flöte, genannt Flötenquartett, ab den 1760er Jahren immer populärer wurde, erfreute sich diese Modeerscheinung auch in Mannheim großer Beliebtheit. Der Konzertmeister und ab 1773 der Kabinettmusikdirektor Carlo Giuseppe Toeschi komponierte – höchstwahrscheinlich ursprünglich für die Musizierstunden seines Dienstherren Carl Theodor – ca. 30 Flötenquartette, die vornehmlich in Paris publiziert wurden. Toeschi wurde zum Vorreiter auf diesem Gebiet, obwohl noch andere Musikerkollegen wie Christian Cannabich, Ignaz Fränzl oder Jean Baptist Wendling Flötenquartette schrieben. Selbst als die Hofkapelle nach München umsiedelte, wurde diese Tradition fortgeführt.