Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

CLEMENTI: Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op

NAXOS NAXOS These four works are among the few surviving examples of Muzio Clementi’s early orchestral music. The two Symphonies, Op. 18 follow Classical models but are full of the surprise modulations and dynamic contrasts to be found in his piano sonatas. The Piano Concerto has a dazzling solo part and some delightful orchestral touches. Clementi’s Symphonies Nos. 1-4 can be heard on Naxos 8.573071 and 8.573112. CLEMENTI: DDD CLEMENTI: Muzio 8.573273 CLEMENTI Playing Time (1752-1832) 58:19 Piano Concerto in C major, Op. 33, No. 3 21:19 7 1 Allegro con spirito 9:30 Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • 2 Adagio cantabile, con grande espressione 5:27 4 7 3 Presto 6:22 3 1 3 4 Minuetto pastorale in D major, WO 36 3:57 3 2 7 Symphony in B fl at major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1787) 16:27 3 5 Allegro assai 4:57 7 6 Un poco adagio 4:37 7 Minuetto (Allegretto) and Trio 4:05 9 www.naxos.com ൿ 8 Allegro assai 2:48 Made in Germany Commento in italiano all’interno Booklet Notes in English & Symphony in D major, Op. 18, No. 2 (1787) 16:36 Ꭿ 9 Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 0 Andante 3:12 ! Minuetto (Un poco allegro) and Trio 3:19 @ Allegro assai 4:15 Bruno Canino, Piano Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Francesco La Vecchia Recorded at the Auditorium di Via Conciliazione, Rome, 28th-29th October 2012 (tracks 1-3) and at the OSR 8.573273 Studios, Rome, 27th-30th December 2012 (tracks 4-12) • Producer: Fondazione Arts Academy 8.573273 Engineer and Editor: Giuseppe Silvi • Music Assistant: Desirée Scuccuglia • Booklet notes: Tommaso Manera Release editor: Peter Bromley • Cover: Paolo Zeccara • Publishers / Editions: Editori s.r.l., Albano Laziale, Rome (tracks 1-3, edited by Pietro Spada); Suvini Zerboni, Milan (track 4); Johann André, Offenbach am Main / Public Domain (tracks 5-8); Jean-Jérôme Imbault, Paris / Public Domain (tracks 9-12) 88.573273.573273 rrrr CClementilementi • 3_EU.indd3_EU.indd 1 119/05/149/05/14 112:022:02. -

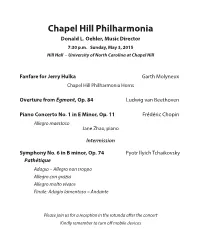

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Composed for Six-Hands Piano Alti El Piyano Için Bestelenen

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC ISSN: 2146-5193, April 2018 Volume 8 Issue 2, p. 340-363 THE FORM ANALYSIS OF “SKY” COMPOSED FOR SIX-HANDS PIANO Şirin AKBULUT DEMİRCİ Assoc. Prof. Education Faculty, Music Education Faculty. Uludag University, Turkey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8904-4920 [email protected] Berkant GENÇKAL Assoc. Prof. State Conservatory, School for Music and Drama. Anadolu University, Turkey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5792-2100 [email protected] ABSTRACT The piano, which is a solo instrument that takes part in educational process, can take role not only in instrumental education but also in chamber music education as well with the 6-hands pieces for three players that perform same composition on a single instrument. According to the international 6-hands piano literature, although the works of Alfred Schnittke's Hommage, Carl Czerny's Op.17 and 741, Paul Robinson's Pensees and Montmartre and many more are included, the Turkish piano literature has been found to have a limited number of compositions. The aim of the work is to contribute to the field by presenting musical analysis about the place and the importance of the educational use of the works composed for 6-hands which are extremely rare in the Turkish piano literature. As an example, the piece named Sky composed by Hasan Barış Gemici is considered. Analysis is supported by comparative methods in form, structuralism, rhythm, theoretical applications and performance; it also gives information about basic playing techniques. It is thought that this study carries importance in contributing to the limited number of Turkish 6-hands piano literature and researchers who will conduct research in this regard, in terms of creating resources for performers and composers who will interpret the literature. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Nicolas Namoradze Honens Prize Laureate Chamber Music / Works for Piano & Voice

NICOLAS NAMORADZE HONENS PRIZE LAUREATE CHAMBER MUSIC / WORKS FOR PIANO & VOICE K. Agócs Immutable Dreams (quintet) Bartók Piano Quintet Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major Op. 12 No. 2 Quintet for Piano and Winds Op. 16 Sonata for Piano and Horn in F Major Op. 17 Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major Op. 24 Sonata for Piano and Cello in A Major Op. 69 Sonata for Piano and Cello in D Major Op. 102 No. 2 Brahms Piano Trio in B Major Op. 8 Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25 selections from Waltzes Op. 39 Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major Op. 78 Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major Op. 99 Piano Trio in C minor Op. 101 Britten Gemini Variations for flute, violin and piano four-hands (Secondo) Cartan Introduction et Allegro for Piano and Wind Quintet Castiglioni Quickly—Variations for Chamber Ensemble Copland Appalachian Spring (chamber version for 13 players) Why do the shut me out of heaven? (voice and piano) Danzon Cubano (Piano I) Rodeo Hoe-Down (Piano I) Debussy Sonata for Piano and Violin L. 140 La Mer (transcription for piano four-hands / Secondo) Jeux (transcription for two pianos: Roques / Primo) Petite Suite (Secondo) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for two pianos / Piano I) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for piano four-hands: Ravel / Secondo) Danses sacrée et profane (transcription for two pianos / Piano II) Dvorak selections from Slavonic Dances Opp. 46 & 72 Dohnányi selections from Ruralia Hungarica Op. -

HUMMEL Mozart’S Symphonies Nos

HUMMEL Mozart’s Symphonies Nos. 38 ‘Prague’, 39 and 40 Arranged for Flute, Violin, Cello and Piano Uwe Grodd • Friedemann Eichhorn Martin Rummel • Roland Krüger Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) his privy council, after acceding to the throne in 1775, was pirated copies of his original manuscripts were always a Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) that of poet, artist and politician Johann Wolfgang von threat. Hummel was suspicious of editions published on the Goethe. The court theatre immediately became the central continent. In a letter to a friend he wrote: “How come … Mozartʼs Symphonies Nos. 38 ʻPragueʼ, 39 and 40 focus of city life and the addition of the new Hoftheater in you do not find a single note from an honourable German arranged by Hummel for flute, violin, cello and piano 1791 ensured the predominance of music. Hummelʼs publisher?” The editions for this recording were made using dedication of his arrangement of the Prague Symphony Hummelʼs English publications from Chappell and Co In 1786, at the age of eight, Hummel went to live and study aus dem Serail. Hummelʼs lack of diplomacy, however, reads “This Symphony is respectfully dedicated to His (1823-4) for which J. R. Schultz acted as intermediary in with Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in Vienna. During his two combined with his disregard of dress codes, “loud and Excellency Baron von Goethe, Minister of State to His London. While England and France had regulations years as a lodger in the familyʼs apartment in the pushy” manner and devotion to his own performing career Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Saxe Weimar by J. -

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’S Op

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Op. 94 for Viola and Orchestra A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2018 by Fan Yang B. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2008 M. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2010 D. M. A. Candidacy, University of Cincinnati, 2013 Abstract The Potpourri for Viola and Orchestra, Op. 94 by Johann Nepomuk Hummel is available in a heavily abridged edition, entitled Fantasy, which causes confusions and problems. To clarify this misperception and help performers choose between the two versions, this document identifies the timeline and sources that exist for Hummel’s Op. 94 and compares the two versions of this work, focusing on material from the Potpourri missing in the Fantasy, to determine in what ways it contributes to the original work. In addition, by examining historical definitions and composed examples of the genre as well as philosophical ideas about the faithfulness to a work—namely, idea of the early nineteenth-century work concept, Werktreue—as well as counter arguments, this research aims to rationalize the choice to perform the Fantasy or Potpourri according to varied situations and purposes, or even to suggest adopting or adapting the Potpourri into a new version. Consequently, a final goal is to spur a reconsideration of the potpourri genre, and encourage performers and audiences alike to include it in their learning and programming. -

Composers and Publishers in Clementi's London

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London Book Section How to cite: Rowland, David (2018). Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London. In: Golding, Rosemary ed. The Music Profession in Britain, 1780-1920: New Perspectives on Status and Identity. Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 32–52. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781351965750/chapters/10.4324%2F9781315265001-3 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 1 Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London David Rowland (The Open University) Clementi was in London by April 1775 and from then until shortly before his death in March 1832 he was involved with the capital’s music publishing industry, first as a composer, but also from 1798 as a partner in one of Europe’s largest and most important music-publishing firms.1 During the course of his career London’s music-publishing industry boomed and composers responded by producing regular streams of works tailored to the needs of a growing musical market. At the same time copyright law began to be clarified as it related music, a circumstance which significantly affected the relationship between composers and publishers. -

Viennese Piano Technique of the 1820S and Implications for Today's

VIENNESE PIANO TECHNIQUE OF THE 1820S AND IMPLICATIONS FOR TODAY’S PIANISTS Table of Contents • ‘…auf diese Art wird sie nichts‘ • PART 1: Viennese posture and touch • A brief summary of instructions in Viennese treatises • Understanding the Viennese fortepiano technique • The significance of early training • Mozart and Nannette • PART 2: Applying the reconstructed Viennese technique • Conclusion • Coda: 5 steps to reconstructing the Viennese piano technique of the 1820s • Endnotes Christina Kobb Christina Kobb is a Norwegian pianist and researcher, specializing in fortepiano performance. After having held the position Head of Theory at Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo, she is currently finishing her PhD at the Norwegian Academy of Music. Christina and is co-founder and editor of Music & Practice. by Christina Kobb Music & Practice, Volume 4 Scientific In this article, I will present my work on reconstructing Viennese piano technique from descriptions of posture and touch in treatises and method books of the 1820s. Prevalent in these sources, is the emphasis on correct execution of basic motions in piano playing. Since these sources were primarily targeted at children, and teachers teaching children, I will open the discussion with a letter from Mozart, where he comments on the piano playing of the eight-year-old Nannette Stein. What does Mozart’s letter tell us about his preferences regarding piano playing – for children, adults, or both? Quite notably, matters of posture and basic movements are discussed in similar ways in his letter and in piano treatises for the following generation. Why do matters of posture seem to have been so important for the piano teachers of that time? In the first part of this article, I highlight their descriptions on posture and touch, along with the reasoning throughout generations regarding the physical approach and technique of piano playing. -

Fourth International Congress for Church Music

caec1 1a Fourth International Congress for Church Music • VOLUME 88, NO. 2 , SUMMER, 1961 CAECILIA Published foiir times a year, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Second-Class Postage Paid at Omaha, Nebraska Subscription Price-$3.00 per year All articles for publication must be in the hands of the editor, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska, 30 days before month of publication. Business Manager: Norbert Letter Change of address should be sent to the circulation manager: Paul Sing, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska Postmaster: Form 3579 to Caecilia, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebr. TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial ______ ·---------------------------- --------······ ... ·------- ·-------·------·-------------------------- .. 51 The Basis of the Relationship Between Chant and Cult Dr. Basilius Ebel ______ --------------------------------------------------------------------- 58 Father William Joseph Finn, C.S.P.-William Ripley Dorr -------------------- 70 Monsignor Quigley-Mary Grace Sweeney ---------------------------------------------- 74 New York Report-James B. Welch ..... ----------------------------- ------------------·-· 76 Musical Programs at the Congress ... -------------- --------------------------------------------- 79 VOLUME 88, NO. 2 SUMMER, 1961 CAECILIA A Quarterlr ReYiew deYoted to the liturgical music apostolate. Published with ecclesiastical approval by the Society of Saint Caecilia in Spring, Summer, Autwnn and Winter. Established in 1874 by John B. Singenberger, K.C.S.G., K.C.S.S. (1849-1924). Editor _______________________ _ _____________