Cadenzas Written for the First Movement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recasting Gender

RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Shelley Smith August, 2009 RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN Shelley Smith Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. James Lynn _________________________________ _________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________________ _________________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. THE SHAPING OF A FEMINIST VERNACULAR AND ITS APPLICATION TO 19TH-CENTURY MUSIC ..............................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 The Evolution of Feminism .....................................................................................3 19th-Century Gender Ideologies and Their Encoding in Music ...............................................................................................................8 Soundings of Sex ...................................................................................................19 II. ROBERT & CLARA SCHUMANN: EMBRACING AND DEFYING TRADITION -

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Concert Program

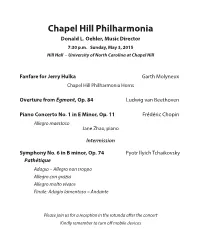

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

Studio N. 114-2020/C

Consiglio Nazionale del Notariato Studio n.114-2020/C IL CONTENUTO ATIPICO DEL TESTAMENTO di Vincenzo Barba (Approvato dalla Commissione Studi Civilistici il 13 ottobre 2020) Abstract Lo studio, movendo da una analisi storica della nozione di testamento intende dimostrare le sue straordinarie potenzialità, precisando che non è l’unico atto di ultima volontà. Si chiarisce che con il testamento la persona può regolare non solo i suoi interessi patrimoniali, ma anche tutti gli interessi non patrimoniali, anche oltre i casi previsti dalla legge. La distinzione tra contenuto tipico e atipico del testamento è servita storicamente per distinguere tra disposizioni patrimoniali e no; essa tuttavia non può servire, nella contemporaneità, né per definire il concetto di testamento, né per individuare la disciplina applicabile. Questa distinzione non serve per escludere la rilevanza testamentaria della regolamentazione degli interessi non patrimoniali, ma per affermare la possibilità di regolamentare questi interessi non soltanto con il testamento, ma anche con l’atto di ultima volontà, diverso dal testamento. Leggendo insieme gli artt. 587 e 588 Cod. civ. non può dirsi che il testamento è limitato al contenuto attributivo, ossia quello che si risolve nell’istituzione di erede o nel legato, ma che il testamento è l’atto regolativo della successione a causa di morte della persona e che al solo testamento è riservata la possibilità di contenere istituzioni di erede o di legato. Con intesa che tutti gli altri profili successori della persona e, in specie quelli non patrimoniali, e comunque, quelli non incidenti sulla delazione possono essere regolati anche con atti di ultima volontà diversi dal testamento, la cui forma deve essere valutata, salvo che non sia espressamente preveduta dalla legge, in ragione degli interessi che l’atto compone e della sua funzione. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

9914396.PDF (12.18Mb)

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Ifigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnaticn Compare 300 North Zeeb Road, Aim Arbor NO 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with indistinct print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THREE SACRED CHORAL/ ORCHESTRAL WORKS BY ANTONIO CALDARA: Magnificat in C. -

Franz Schubert: Inside, out (Mus 7903)

FRANZ SCHUBERT: INSIDE, OUT (MUS 7903) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2017 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Thursdays, 2:00–4:50 M&DA 273 office hours Fridays, 9:30–10:30 prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Blake Howe / Franz Schubert – Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the life, works, and times of Franz Schubert (1797–1828), one of the most important composers of the nineteenth century. We begin by attempting to understand Schubert’s character and temperament, his life in a politically turbulent city, the social and cultural institutions that sponsored his musical career, and the circles of friends who supported and inspired his artistic vision. We turn to his compositions: the influence of predecessors and contemporaries (idols and rivals) on his early works, his revolutionary approach to poetry and song, the cultivation of expression and subjectivity in his instrumental works, and his audacious harmonic and formal practices. And we conclude with a consideration of Schubert’s legacy: the ever-changing nature of his posthumous reception, his impact on subsequent composers, and the ways in which modern composers have sought to retool, revise, and refinish his music. COURSE MATERIALS Reading assignments will be posted on Moodle or held on reserve in the music library. Listening assignments will link to Naxos Music Library, available through the music library and remotely accessible to any LSU student. There is no required textbook for the course. However, the following texts are recommended for reference purposes: Otto E. -

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp.