'All You Can Eat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REYNOLDS, Brian

BRIAN J. REYNOLDS DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY https://vimeopro.com/user5249916/brian-j-reynolds-director-of-photography TELEVISION DOLLY PARTON’S HEARTSTRINGS: Netflix Prod: Patrick Sean Smith, Sam Haskell, Dir: Joe Lazarov THESE OLD BONES (Anthology Feature) Dolly Parton, Hudson Hickman DO UNTO OTHERS (MOW) Lifetime Prod: Julie Jarrett-Insogna, Stefanie Ziev Dir: Seth Jarret DOLLY PARTON’S (MOW) NBC/Warner Bros. Prod: Sam Haskell, Hudson Hickman Dir: Stephen Herek CIRCLE OF LOVE COAT OF MANY COLORS (MOW) NBC/Warner Bros. Prod: Sam Haskell, Hudson Hickman Dir: Stephen Herek MANHATTAN LOVE STORY (Season 1) ABC Prod: Jeff Lowell, Peter Traugott, Robin Schwartz Dir: Michael Fresco 90210 (Seasons 4 & 5) CBS/The CW Prod: Michael Pendell, Patricia Carr, Lara Olsen Dir: Various UNITED STATES OF TARA (Eps. 305-308) DreamWorks/Showtime Prod: Darryl Frank, Dan Kaplow Dir: Various THE GOOD GUYS (Pilot & Series) Fox TV Studios/FOX Prod: Matt Nix Dir: Tim Matheson BETTER OFF TED (Season 2) 20th Century Fox/ABC Prod: Marc Solakian, Michael Shipley Dir: Michael Fresco LIMELIGHT (Pilot) Warner Bros./ABC Prod: K.J. Steinberg, McG Dir: David Semel THE CLOSER (Seasons 1-4) Warner Bros./TNT Prod: Michael Robin, Greer Shephard Dir: Michael Robin CLEANER (Pilot) CBS Paramount/A&E Prod: Jonathan Prince, Robert Paul Munic Dir: David Semel TRUST ME (Pilot) Warner Horizon/TNT Prod: Hunt Baldwin, John Coveny Dir: Michael Robin THE VIRGIN OF AKRON OHIO (Pilot) Fox TV Studios/Lifetime Prod: Cary Brokaw, Jordan Budde Dir: Randall Zisk IMPERFECT UNION (Pilot) TNT Prod: -

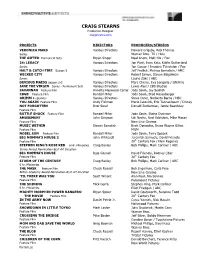

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer Craigstearns.Com

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer craigstearns.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS VERONICA MARS Various Directors Howard Grigsby, Rob Thomas Series Warner Bros. TV / Hulu THE GIFTED Permanent Sets Bryan Singer Neal Ahern, Matt Nix / Fox 24: LEGACY Various Directors Jon Paré, Evan Katz, Kiefer Sutherland Series Jon Cassar / Imagine Television / Fox HALT & CATCH FIRE Season 3 Various Directors Jeff Freilich, Melissa Bernstein / AMC WICKED CITY Various Directors Robert Simon, Steven Baigelman Series Laurie Zaks / ABC DEVIOUS MAIDS Season 2-3 Various Directors Marc Cherry, Eva Longoria / Lifetime JANE THE VIRGIN Series - Permanent Sets Various Directors Lewis Abel / CBS Studios SAVANNAH Feature Film Annette Haywood-Carter Jody Savin, Jay Sedrish CBGB Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Brad Rosenberger GRIMM 8 episodes Various Directors Steve Oster, Norberto Barba / NBC YOU AGAIN Feature Film Andy Fickman Mario Iscovich, Eric Tannenbaum / Disney NOT FORGOTTEN Dror Soref Donald Zuckerman, Jamie Beardsley Feature Film BOTTLE SHOCK Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Elaine Dysinger AMUSEMENT John Simpson Udi Nedivi, Neal Edelstein, Mike Macari Feature Film New Line Cinema MUSIC WITHIN Steven Sawalich Brett Donowho, Bruce Wayne Gillies Feature Film MGM NOBEL SON Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Terry Spazek BIG MOMMA’S HOUSE 2 John Whitesell Jeremiah Samuels, David Friendly th Feature Film 20 Century Fox / New Regency STEPHEN KING’S ROSE RED 6 Hr. Miniseries Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC Emmy Award Nomination-Best Art Direction BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE Raja Gosnell David Friendly, Rodney Liber th Feature Film 20 Century Fox STORM OF THE CENTURY Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC 6 hr. -

Examining Television Narrative Structure

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2002 Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure M. J. Porter D. L. Larson Allison Harthcock Butler University, [email protected] K. B. Nellis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/9/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure. This is an electronic version of an article published in Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. The print edition of Journal of Popular Film and Television is available online at: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/VJPF Television's narratives serve as our society's major storyteller, reflecting our values and defining our assumptions about the nature of reality (Fiske and Hartley 85). On a daily basis, television viewers are presented with stories of heroes and villains caught in the recurring turmoil of interrelationships or in the extraordinary circumstances of epic situations. -

Criminal Minds: Haunted

“Haunted” Written by Erica Messer Directed by Jon Cassar © 2009 ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. PRODUCTION #502 Episode Ninety-Three Final Draft(PINK) July 29, 2009 Copyright © 2009 ABC Studios All Rights Reserved CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” Script Revision History DATE COLOR PAGES 7/25/2009 BLUE CAST, SET, 1-63 7/29/2009 PINK CAST, SET, 1-64 CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” CAST LIST ROSSI HOTCH PRENTISS MORGAN REID JENNIFER GARCIA DARRIN CALL YOUNG CALL PHARMACIST STOCK BOY * LOCAL REPORTER LIEUTENANT KEVIN MITCHELL DR. CHARLES CIPOLLA PATIENT YOUNG TOMMY WOMAN THOMAS (TOMMY) ANDERSON BILL JARVIS YOUNG BILL JARVIS FEATURED EXTRAS BANK GUARD CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIORS BAU JET BAU JET – DAY (STOCK) * BAU Runway High Tech Room Rossi’s Office COUNTRY ROAD - DAY PHARMACY LOUISVILLE STREET – DAY Counter Alley Aisles JARVIS HOUSE - DAY HOTCH’S APARTMENT KENTUCKY – DAY (STOCK) LOUISVILLE METRO P.D. MACHINE SHOP – DAY * CIPOLLA’S OFFICE LOUISVILLE METRO P.D. – DAY CIPOLLA’S OFFICE – DAY STREET – DAY DARRIN CALL’S APARTMENT CURBSIDE – DAY TOMMY ANDERSON’S HOUSE STERNER ORPHANAGE – DAY JARVIS HOUSE HITCHENS AVENUE - DAY MOVING SHOTS BAU SUV – Hotch & Morgan MINIVAN – Call & Ryan CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” TIME SPAN This episode takes place over 1 day. Teaser: Day 1 Act One: Day 1 Act Two: Day 1 Act Three: Day 1 Act Four: Day 1, Night 1 CRIMINAL MINDS "Haunted" PINK 7/29/09 1. -

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2011 Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

The West Wing Weekly 5.04: “Han” Guest: Paula Yoo

The West Wing Weekly 5.04: “Han” Guest: Paula Yoo [Frédéric Chopin – Prelude in E-minor (Op.28, No.4) excerpt] HRISHI: Here we go. JOSH: Hi guys. Wipe away those tears and listen to The West Wing Weekly. There's hope, there's always hope. [laughter] I'm Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: For those of you wondering, I was playing left hand, [Hrishi laughs] and Hrishi was playing right hand. HRISHI: Today, we're talking about “Han.” It's episode 4 of season 5 of The West Wing. JOSH: This episode was written by Peter Noah. Peter Noah would later go on to many things, including being a consulting producer on, I believe, 40 episodes of Scandal. He's a great writer, and story credit for this episode goes to Peter Noah and Mark Goffman. That's Peter Noah & Mark Goffman and, A-N-D, Paula Yoo. The direction is by the always-magnificent Christopher Misiano. The episode first aired on October 22nd, 2003. HRISHI: In this episode, a North Korean pianist comes to the White House for a performance, but things get complicated when he tells the president he wants to defect. C.J.'s for it, but everyone else is pretty much against it, and the president has to weigh both arguments. Meanwhile, Will is having a hard time writing an inspiring speech about the nomination and confirmation of vice president-to-be Bob Russell. Josh is battling one congressman who plans to be a holdout vote against the nomination. Toby wants to get away from speechwriting, but every time he thinks he's out, they keep pulling him back in. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

James Immekus

MANAGEMENT 101 JAMES IMMEKUS FILM UNBROKEN 2: PATH TO REDEMPTION Co-Star Dir Harold Cronk FRIENDED TO DEATH Lead Dir. Sarah Smick THE CARETAKER Lead Dir. Bryce Olson BOXBOARDERS! Lead Dir. Rob Hedden SPARE CHANGE Co-Star Dir. Arturo Guzman, Jon Talbert TELEVISION GOOD GIRLS Guest Star NBC, Dylan K. Massin THE GOOD DOCTOR Guest Star ABC, Mike Listo ONCE UPON A TIME Recurring ABC, Ferland, Goddard, Underwood SUPERNATURAL Guest Star CW, Jerry Wanek CRIMINAL MINDS Guest Star CBS, Michael Lange VEGAS Guest Star CBS, Duane Clark EMILY OWENS M.D. Guest Star CW, Jamie Babbit THE GLADES Guest Star A&E, Kelly Makin CSI Guest Star CBS, Louis Milito IN PLAIN SIGHT Guest Star USA, Anton Cropper JUSTIFIED Guest Star F/X, Michael Watkins LIE TO ME Guest Star FOX, Elodie Keene MAD MEN Guest Star AMC, Lesli Linka Glatter GREY’S ANATOMY Guest Star ABC, Rob Corn THE CLEANER Guest Star A&E, David Semel GHOST WHISPERER Guest Star CBS, Steven Robman SHARK Guest Star CBS, Paul Holahan MEDIUM Guest Star NBC, Miguel Sandoval BONES Guest Star FOX, Dwight Little WITHOUT A TRACE Guest Star CBS, Peter Markle HOUSE Guest Star FOX, Dan Attias COLD CASE Guest Star CBS, Paris Barclay CHARMED Guest Star WB, Michael Grossman DRAKE & JOSH Guest Star Nickelodeon, Steve Hoefer NUMB3RS Co-Star CBS, Tim Matheson THEATRE HOUSE OF BLUE LEAVES Ronnie Mark Taper Forum (CTG), Nicki Martin FINDING THE SUN Fergus Goodman Theatre, Eric Rosen WILDER Wilder CATF, Lisa Portes MARVIN’S ROOM Hank Interact Theatre Co. Dave Floric WEB SERIES CANTRIPS Recurring GeekandSundry, Canaan Triplett HITTING THE BREAKS Recurring Pureflix, Gabriel Sabloff TRAINING BFA Acting DePaul University Theatre School (Goodman School of Drama) Comedy Improv Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB) SPECIAL SKILLS Improv (Viola Spolin), Certified Acting Combatant of the Society of American Fight Directors, Percussionist, Didgeridoo, Dialects Theatrical Agent | HRI (310) 295-0775 Commercial Agent | AKA (323) 965-5600 Management 101 (818) 753-5200 • [email protected] . -

Jos Viramontes Resume

Jos Viramontes SAG-AFTRA TELEVISION THE BRAVE Guest Star NBC / Mikael Salomon GREY’S ANATOMY Recurring ABC / Kevin McKidd MAJOR CRIMES Recurring TNT / Patrick Duffy FAMOUS IN LOVE Recurring FREEFORM / Tanya Hamilton NCIS: LOS ANGELES Guest Star CBS / Terrence O’Hara BATTLE CREEK Guest Star CBS / Richard Lewis ALMOST HUMAN Guest Star FOX / Michael Offer SOUTHLAND Guest Star TNT / Jimmy Muro JANE BY DESIGN Guest Star ABC Family / Lev L Spiro BONES Guest Star FOX / Milan Cheylov LIE TO ME Guest Star FOX / Lesli Linka Glatter CSI Guest Star CBS / Andrew Bernstein ELI STONE Guest Lead ABC / Michael Schultz JOURNEYMAN Guest Star NBC / Alex Graves SHARK Guest Star CBS / Seith Mann THE SHIELD Guest Star FX / Guy Ferland LONELY GIRL 15 Recurring Webseries / Marcello Darciano CSI: NY Co-Star CBS / Oz Scott ER Co-Star NBC / Lesli Linka Glatter CLOSE TO HOME Co-Star CBS / Karen Gaviola FILM BRIGHT Supporting David Ayer THE WOMAN WHO SLIPPED BETWEEN BLOOD AND SAND Lead Kevin Thomas FAUX Supporting Oui Films JOYFUL PARTAKING Supporting Puzzle Box Productions MONEY BUYS HAPPINESS Supporting Millennium Films THEATRE - Partial Oregon Shakespeare Festival KING LEAR Edmund Jim Edmondson MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING Claudio Laird Williamson THE ROYAL FAMILY Anthony, McDermott Peter Amster ROMEO AND JULIET Romeo, Tybalt Loretta Greco RICHARD II Aumerle Libby Appel THE WINTER’S TALE Florizel Michael Edwards AS YOU LIKE IT Oliver Penny Metropulos SATURDAY, SUNDAY, MONDAY Rocco Libby Appel TWO SISTERS AND A PIANO Victor Manuel Andrea Frye THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR -

Directors Guild of America Creative Rights Handbook 2011 - 2014

DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA CREATIVE RIGHTS HANDBOOK 2011 - 2014 Los Angeles, CA (310) 289-2000 New York, NY (212) 581-0370 Chicago, IL (312) 644-5050 www.dga.org Taylor Hackford, President • Jay D. Roth, National Executive Director Dear Colleague, As Co-Chairs of the DGA Creative Rights Committee, we spend a lot of time talking to Directors about their Theatrical Creative Rights work problems. Often we nd that trouble begins with Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS those who are unclear about or unaware of creative Jonathan Mostow Steven Soderbergh rights protections they already have as members of the Co-Chair Co-Chair Directors Guild of America. David Ayer Taylor Hackford Donald Petrie CREATIVE RIGHTS CHECKLISTS Some DGA Directors have voiced frustration over Michael Bay John Lee Hancock Sam Raimi Checklists of DGA Directors’ creative rights, practices in the editing room; they did not know John Carpenter Curtis Hanson Brett Ratner codied in this handbook that the DGA Basic Agreement protects them from .…..................….…….…….…….…….….3 interference when they are preparing their cut. Some omas Carter Mary Lambert Jay Roach television Directors have expressed concern about being Martha Coolidge Jonathan Lynn Tom Shadyac excluded from the looping and dubbing process; they Wes Craven Michael Mann Brad Silberling were unaware that they, like feature Directors, have SUMMARY OF CREATIVE RIGHTS Andy Davis Frank Marshall Penelope Spheeris the right to participate in both. And many Directors A summary of a Director’s creative rights did not realize that, because they are Guild members, Roger Donaldson McG Betty omas under the Directors Guild of America Basic they have a right to additional cutting time if necessary David Fincher E.