A Guide to Atlanta's Archives David B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

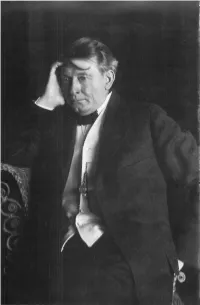

Agrarian-Rebel-Biogr

C. VANN WOODWARD TOM WATSON Agrarian Rebel THE BEEHIVE PRESS SAVANNAH • GEORGIA Contents I The Heritage I II Scholar and Poet IO III "Ishmael" in the Backwoods 27 IV The "New Departure" 44 V Preface to Rebellion 62 VI The Temper of the 'Eighties 7i VII Agrarian Law-making 81 VIII Henry Grady's Vision 96 IX The Rebellion of the Farmers no X The Victory of 1890 125 XI "I Mean Business" 143 XII Populism in Congress 163 XIII Race, Class, and Party 186 XIV Populism on the March 210 XV Annie Terrible 223 XVI The Silver Panacea 240 XVII The Debacle of 1896 261 XVIII Of Revolution and Revolutionists 287 XIX From Populism to Muckraking 307 XX Reform and Reaction 320 XXI "The World is Plunging Hellward" 343 XXII The Shadow of the Pope 360 XXIII The Lecherous Jew 373 XXIV Peter and the Armies of Islam 390 XXV The Tertium Quid 411 Bibliography 422 Index i V Preface to the 1973 Reissue THE reissue OF an unrevised biography thirty-five years after its original publication raises some questions about the effect that history has on historical writing as well as the effect that changing fashions of historical writing have on history written according to earlier fashions. Among the many historical events of the last three decades that have altered the perspective from which this book was writ ten, perhaps the most outstanding has been the movement for political and civil rights of the black people. All that was still in the unforeseeable future in 1938. At that time the Negro was still thoroughly disfranchised in the South, and no white South ern politician dared speak out for the political or civil rights of blacks. -

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell Collection, 1922-1991

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Mitchell, Margaret. Title: Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 265 Extent: 3.75 linear feet (8 boxes), 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and AV Masters: .5 linear feet (1 box, 1 film, 1 CLP) Abstract: Papers of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell including correspondence, photographs, audio-visual materials, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Requests to publish original Mitchell material should be directed to: GWTW Literary Rights, Two Piedmont Center, Suite 315, 3565 Piedmont Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30305. Related Materials in Other Repositories Margeret Mitchell family papers, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia and Margaret Mitchell collection, Special Collections Department, Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. Source Various sources. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Manuscript Collection No. -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Joel Chandler Harris (Uncle Remus) Sketches from His Life and Works

CCHA Report, 13 (1945-46), 27-42 Joel Chandler Harris (Uncle Remus) Sketches from his Life and Works by MARGARET EVERHART In the year 1862, an advertisement in a local newspaper in Georgia ran thus: “ An active, intelligent white boy 14-15 years of age, is wanted at this office to learn the printer’s business”. The war between the Northern and Southern states was still raging, the dead and wounded of both sides exemplifying the immortal words of the poet, Robert Burns – “ Man’s inhumanity to man”. The Countryman, in which the advertisement appeared, was owned by Joseph Addison Turner Esq., – lawyer, journalist, cotton planter, merchant and owner of “Turnwald Plantation”. After answering the advertisement in his own handwriting and composition, which, surprised Mr. Turner, the boy, Joel C. Harris, found himself installed as an apprentice, beginning in the humble capacity of printer’s devil. The Countryman was operated in an outhouse on the stately plantation of “Turnwald” in Putnam County, where the noise of battle scarcely penetrated the solitary pine woods, “ The Forest Primeval”. As Joel advanced in his work, operating a hand-press (an old Washington no. 2, which had seen considerable service) he also progressed in other departments, for he was a young man with ambition. It was not long before he was setting type quickly and accurately. “ He was the fastest pressman on a hand press”. Before many months, he became assi s t an t to the foreman, who was also compositor and pressman. Young Joel was happy with the life on the plantation, and felt quite at home, especially among the books of Mr. -

Georgia Women of Achievement Honorees Name Year City Andrews

Georgia Women of Achievement Honorees Name Year City Andrews, Eliza Frances (Fanny) 2006 Washington Southern writer (1840-1931) incl 2 botany books Andrews, Ludie Clay 2018 Milledgeville 1st black registered nurse in Georgia, founder of Grady nursing school for colored nurses. Anthony, Madeleine Kiker 2003 Dahlonega community activist for Dahlonega Atkinson, Susan Cobb Milton 1996 Newnan influenced her governor-husband to fund grants for women to attend college; successfully petitioned legislature to create what would be Georgia College & St Univ at Milledgeville; appointed postmistress of Newnan by Pres TRoosevelt. Bagwell, Clarice Cross 2020 Cumming Trailblazer in Georgia education; Bagwell School of Education at KSU Bailey, Sarah Randolph 2012 Macon eductor, civic leader, GS leader Bandy, Dicksie Bradley 1993 Dalton entrepreneur - carpet industry; initiated economic revitalization of NW Georgia aftr Great Depression via homemade tufted bedspreads; philanthropist; benefactor to Cherokee Nation Barrow, Elfrida de Renne 2008 Savannah author, poet Beasley, Mathilda 2004 Savannah black Catholic nun who ran a school for black children Berry, Martha McChesney 1992 Rome educator, founder Berry College Black, Nellie Peters 1996 Atlanta social & civic leader; pushed for womens' admittance to UGA; aligned with Pres TRoosevelt re agricultural diversification & Pres Wilson re conservation. Bosomworth, Mary Musgrove 1993 Savannah cultural liaison between colonial Georgia & her Native American community Bynum, Margaret O 2007 Atlanta 1st FT consultant -

The ATLANTA HISTORICAL BULLETIN

The ATLANTA HISTORICAL BULLETIN Published by the ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Vol. VIII January, 1947 No. 31 The Bulletin is the organ of the Atlanta Historical Society and is sent free to its members. All persons in terested in the history of Atlanta are invited to join the Society. Correspondence concerning contributions for the Bulletin should be sent to the Joint Editors, Stephens Mitchell, 605 Peters Building, Atlanta, or to Franklin M. Garrett, The Coca-Cola Company, Atlanta. Applications for membership and dues should be sent to the Executive Secretary, Miss Ruth Blair, at the office of the Society, 1753 Peachtree St., N. W. Single numbers of the Bulletin may be obtained from the secretary. Members of the Atlanta Historical Society, wnen making their wills, are requested to remember this organi zation. Legacies of historical books, papers, pictures and museum materials, in additon to funds, are wanted for the Society. The latter are particularly needed with which to complete payment for the new home and for its main tenance and furnishing. CurtiHB Printing Co., Inc., Atlanta ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Officers, Members of Advisory Council, and Board of Directors, 191+7 WALTER MCELREATH Honorary President for Life and Chairman, Board of Directors HENRY A. ALEXANDER President GORDON F. MITCHELL Vice-President JOHN ASHLEY JONES Treasurer FRANKLIN M. GARRETT Secretary STEPHENS MITCHELL \ _ _ _ _Joint Editors FRANKLIN M. GARRETT j RUTH BLAIR Executive Secretary Advisory Council, Term ending January, 191+8 A. G. DEVAUGHN E. KATHERINE ANDERSON JOHN ASHLEY JONES JOHN M. HARRISON A. A. MEYER MRS. P. THORNTON MARYE JOSIAH T. -

Recipes Exist in the Moment: Cookbooks and Culture in the Post-Civil War South

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Recipes Exist In The Moment: Cookbooks And Culture In The Post-Civil War South Kelsielynn Ruff University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ruff, Kelsielynn, "Recipes Exist In The Moment: Cookbooks And Culture In The Post-Civil War South" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 634. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/634 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “RECIPES EXIST IN THE MOMENT”: COOKBOOKS AND CULTURE IN THE POST-CIVIL WAR SOUTH A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by Kelsielynn Ruff August 2013 Copyright Kelsielynn Ruff 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Cookbooks manifested Southern archetypes between the late 1860s and the early 2000s. From the late 1800s through 1945, cookbooks exemplified Jim Crow with racist language, stereotyped illustrations, and marginalization of black laborers. Almost at the same time, an ideological belief that glorified the South’s loss in the Civil War and romanticized the leaders and fallen soldiers as heroes, called the Lost Cause, appeared in cookbooks. Whites used reminiscence about antebellum society, memorialization of Civil War heroes, and coded language to support Lost Cause beliefs. As the twentieth century progressed, the racial tensions morphed, and the civil rights movement came to a head. -

Capturing the Spirit of Oakland 2020 Film

YOUR GUIDE TO THE CAPTURING THE SPIRIT OF OAKLAND 2020 FILM Produced by Historic Oakland Foundation THE RESIDENTS Mary Bohnefeld Benjamin Blanton 1845-1915. Block 161, Lot 11 1845-1927. Block 59, Lot 2, Grave 5 Matron Mary Bohnefeld was born in Heidelberg, Germany Benjamin Blanton was born into slavery in Oglethorpe on July 27, 1845. At age 20, she immigrated alone to the County, Georgia around 1845. His parents were Anthony United States, moving first to New York City, where she and Celia Blanton, and Benjamin was one of ten children. supported herself through sewing. In 1866, she married He moved to Atlanta by 1875 and worked as a gardener and fellow German immigrant and Union soldier, Dietreich farmer until 1877 when he joined the Oakland Cemetery Emwald, with whom she had two children. Following the staff as a gardener and gravedigger. end of his military career, the family moved to Atlanta, While the records are unclear, Benjamin Blanton appears where Dietreich died in 1873. In 1880, Mary married to have been married three times, outliving all of his wives Charles Bohnefeld, a carpenter and undertaker in Atlanta. and most of his children. Benjamin’s life was marked by The marriage was not a happy one, and the couple divorced many personal tragedies but remained close to his sup- in 1892. After working her way up from cook to nurse at portive family. Benjamin lived out his final years in a home Grady Hospital and occasionally providing medical support he shared with his brother, John, on what was then called to the Atlanta Police Department, Mary accepted the official Hunter Street, located just outside of Oakland’s main gate. -

Untitled MS, , N.D., Rebecca Latimer Felton Papers, UGA

BLOOD AND IRONY Blood Irony Southern White Women’s &Narratives of the Civil War, – The University of North Carolina Press . © The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Designed by Kristina Kachele Set in Minion by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gardner, Sarah E. Blood and irony: Southern white women’s narratives of the Civil War, – / Sarah E. Gardner. p. cm. Based on the author’s doctoral thesis, Emory University. Includes bibliographical references and index. --- (cloth: alk. paper) . Confederate States of America—Historiography. United States—History—Civil War, –— Historiography. Southern States—Intellectual life—– . Group identity—Southern States— History. United States—History—Civil War, –—Personal narratives, Confederate. United States—History—Civil War, –— Literature and the war. American literature— Women authors—History and criticism. Women and literature—Southern States—History. Southern States—In literature. Group identity in literature. I. Title. . .''—dc Contents Acknowledgments, ix . Everywoman Her Own Historian, . Pen and Ink Warriors, –, . Countrywomen in Captivity, –, . A View from the Mountain, –, . The Imperative of Historical Inquiry, –, . Righting the Wrongs of History, –, . Moderns Confront the Civil War, –, . -

American Traditional Music in Max Steiner's Score for Gone with the Wind

AMERICAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC IN MAX STEINER'S SCORE FOR GONE WITH THE WIND Heather Grace Fisher A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC December 2010 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Per Broman ii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Film composer Max Steiner’s score for Gone with the Wind (1939) showcases a substantial amount of American traditional music from the nineteenth century. The overwhelming amount of music included in the film has left it neglected in film music studies. My analysis of the traditional music in the soundtrack will demonstrate multiple considerations of how the music works within the film. The first chapter delves into the source of the film, the novel Gone with the Wind (1936) by Margaret Mitchell. This discussion includes an analysis of the major musical moments in the novel. The second chapter examines the film production itself, especially the difficulties that Max Steiner and his fellow composers and arrangers working on the film experienced while writing the score. The final chapter investigates the historical and political context of the American traditional songs Steiner included in the soundtrack and how they function within the film. iii This work is dedicated with love and gratitude to my parents, Mike and Kathy Fisher, and my sister, Megan. Your unfailing support and encouragement mean more to me than you will ever know. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks first must go to God, the Almighty Father for all the grace He has bestowed upon me. I would also like to thank my wonderful parents and sister for all the support they have given me and for putting up with me during this process. -

Oakland Cemetery

TENNELLE STREET SE BOULEVARD Fulton Cotton Mill CSX Rail Yard Martin Luther King Loft Apartments Historic District DECATUR STREET SE King Memorial CSX RAIL LINE Transit Station Richards Mausoleum CABBAGETOWN 3 Potter’s Field north Beaumont Allen Bell Tower Greenhouse BEREAN AVENUE SE SAVANNAH STREET Ridge Bell Tower CARROLL STREET SE Visitors Center 11 and Museum BOULEVARD Shop PICKETT STREET SE 1 Greenhouse Valley African American Grounds GRANT STREET SE 2 “Out in the Rain” Fountain Margaret Mitchell 4 8 Champion Tree Bishop GASKILL STREET SE Lion of Atlanta 10 Wesley 12 13 Carrie Steele Logan Gaines 14 Selena Sloan Butler Agave BIGGERS STREET SE Maynard 5 Holbrook Confederate Memorial Jackson Original Six Acres PARKING Grounds East Hill 7 Julia Collier Harris 15 Women’s Comfort Station MLK JR. DRIVE SE Main Entrance BUS ISWALD STREET SE BOULEVARD Dr. James Nissen 6 BEREAN AVENUE SE DROP-OFF 17 Ivan Allen, Jr. OAKLAND AVENUE s ’ e ZONE Jewish n i t s u Hill Dr. Joseph Jacobs g Bobby Jones 16 u Pedestrian Entrance 9 A GRANT STREET SE MEMORIAL DRIVE MEMORIAL DRIVE MEMORIAL DRIVE to Petit Chou, to I85/I75,to Georgia State Captial e Muchacho, to Your Pie, s r r t s s u é e ’ ’ n e i f Golden Eagle, e e e r s y o o P a k t g d Farm Burger e z u i r H r r C l v z n e Grindhouse o i a u a u t a e e to I20 U L l H c B T a o M t z Killer Burger d l Y n C a o i e k a e o m z i r T a e C r o z c a M i F v a r My Friend’s My Friend’s o N P P a PARK AVENUE F o x S J BOULEVARD i t t s t ’ Growler Shop Growler i S a n c y l i p LOOMIS AVENUE l a e e r e WOOD STREET SE b HARDEN STREET GRANT STREET OAKLAND AVENUE r v h i G u e C to Grant Park and the Atlanta Zoo F CHEROKEE AVENUE p R c e o R WOODWARD AVE. -

The Atlanta Historical Journal

•<h '\^\e' The Atlanta Historical Journal WINTER 1979-80 Volume XXIII Number 4 The Atlanta Historical Journal Franklin M. Garrett Editor Emeritus Ann E. Woodall Editor Harvey H. Jackson Book Review Editor Volume XXRI, Number 4 Winter 1979/80 Copyright 1980 by Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. Atlanta, Georgia COVER: This drawing of an Agnes Scott student holding a basketball was rendered by Philip Shutze for the 1912 Silhouette. The Atlanta Historical Journal is published quarterly by the Atlanta Historical Society, P.O. Box 12423, Atlanta, Georgia, 30355. Subscriptions are available to non-members of the Society. Manuscripts, books for review, exchange journals, and subscription inquiries should be sent to the Editor. If your copy of the Journal is damaged in the mail, please call the Society for a replacement. Please notify the Society of changes in address. TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers, Trustees, Past Presidents, and Past Chairmen of the Board 4 Publications Committee, Editorial Review Board, Staff 5 Editor's Note 6 Nellie Peters Black: Turn of the Century "Mover and Shaker" By Jane Bonner Peacock 7 The Role of Women in Atlanta's Churches, 1865-1906 By Harvey K. Newman 17 "Not a Veneer or a Sham": The Early Days of Agnes Scott By Amy Friedlander 31 Woman Suffrage Activities in Atlanta By A. Elizabeth Taylor 45 Women Authors of Atlanta: A Selection of Representative Works with an Analytic Commentary By Barbara B. Reitt 55 The High Heritage By Carlyn Gaye Crannell 71 Women Architects in Atlanta, 1895-1979 By Susan Hunter Smith 85 Book Reviews 109 New Members 126 In Memoriam 127 Academic Advisory Board, "Atlanta Women from Myth to Modern Times" 128 THE ATLANTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS Stephens Mitchell Chairman Emeritus, Board of Trustees Beverly M.