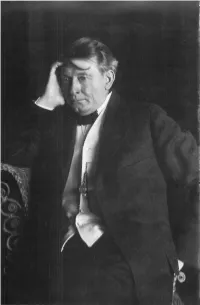

Joel Chandler Harris (Uncle Remus) Sketches from His Life and Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agrarian-Rebel-Biogr

C. VANN WOODWARD TOM WATSON Agrarian Rebel THE BEEHIVE PRESS SAVANNAH • GEORGIA Contents I The Heritage I II Scholar and Poet IO III "Ishmael" in the Backwoods 27 IV The "New Departure" 44 V Preface to Rebellion 62 VI The Temper of the 'Eighties 7i VII Agrarian Law-making 81 VIII Henry Grady's Vision 96 IX The Rebellion of the Farmers no X The Victory of 1890 125 XI "I Mean Business" 143 XII Populism in Congress 163 XIII Race, Class, and Party 186 XIV Populism on the March 210 XV Annie Terrible 223 XVI The Silver Panacea 240 XVII The Debacle of 1896 261 XVIII Of Revolution and Revolutionists 287 XIX From Populism to Muckraking 307 XX Reform and Reaction 320 XXI "The World is Plunging Hellward" 343 XXII The Shadow of the Pope 360 XXIII The Lecherous Jew 373 XXIV Peter and the Armies of Islam 390 XXV The Tertium Quid 411 Bibliography 422 Index i V Preface to the 1973 Reissue THE reissue OF an unrevised biography thirty-five years after its original publication raises some questions about the effect that history has on historical writing as well as the effect that changing fashions of historical writing have on history written according to earlier fashions. Among the many historical events of the last three decades that have altered the perspective from which this book was writ ten, perhaps the most outstanding has been the movement for political and civil rights of the black people. All that was still in the unforeseeable future in 1938. At that time the Negro was still thoroughly disfranchised in the South, and no white South ern politician dared speak out for the political or civil rights of blacks. -

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell Collection, 1922-1991

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Mitchell, Margaret. Title: Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 265 Extent: 3.75 linear feet (8 boxes), 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and AV Masters: .5 linear feet (1 box, 1 film, 1 CLP) Abstract: Papers of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell including correspondence, photographs, audio-visual materials, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Requests to publish original Mitchell material should be directed to: GWTW Literary Rights, Two Piedmont Center, Suite 315, 3565 Piedmont Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30305. Related Materials in Other Repositories Margeret Mitchell family papers, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia and Margaret Mitchell collection, Special Collections Department, Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. Source Various sources. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Manuscript Collection No. -

Southern Ambivalence: the Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris William R. Bell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, William R., "Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625262. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mr8c-mx50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Southern Ambivalence: h The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William R. Bell 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626489 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626489 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Atlanta and The Permanent Things William F. Campbell, Secretary, The Philadelphia Society Part One: Gone With the Wind The Regional Meetings of The Philadelphia Society are linked to particular places. The themes of the meeting are part of the significance of the location in which we are meeting. The purpose of these notes is to make our members and guests aware of the surroundings of the meeting. This year we are blessed with the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, and in particular The Georgian Terrace Hotel. Our hotel is filled with significant history. An overall history of the hotel is found online: http://www.thegeorgianterrace.com/explore-hotel/ Margaret Mitchell’s first presentation of the draft of her book was given to a publisher in the Georgian Terrace in 1935. Margaret Mitchell’s house and library is close to the hotel. It is about a half-mile walk (20 minutes) from the hotel. http://www.margaretmitchellhouse.com/ A good PBS show on “American Masters” provides an interesting view of Margaret Mitchell, “American Rebel”; it can be found on your Roku or other streaming devices: http://www.wgbh.org/programs/American-Masters-56/episodes/Margaret-Mitchell- American-Rebel-36037 The most important day in hotel history was the premiere showing of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and Olivia de Haviland stayed in the hotel. Although Vivien Leigh and her lover, Lawrence Olivier, stayed elsewhere they joined the rest for the pre-Premiere party at the hotel. Our meeting will be deliberating whether the Permanent Things—Truth, Beauty, and Virtue—are in fact, permanent, or have they gone with the wind? In the movie version of Gone with the Wind, the opening title card read: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.. -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Joel Chandler Harris, Interpreter of the Negro Soul

JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS, LXTERPRETER OF THE NEGRO SOUL BY J. V. NASH THE most enduring of all literature springs from popular folk- lore. It is more than poetry or prose ; it is philosophy, science, psychology, religion, history, ethics. It reflects the groping and aspir- ing soul of a people, in all its manifold reactions to its environment. It is the key which long generations of humble folk have been pain- fully forging, with which to unlock the mysterious door which opens into the Unseen. This unpretending folklore is usually kept alive by word of mouth for many generations before a literary genius discovers it, gathers it together, separates the chaff from the wheat, and gives to the world the harvest of golden grain. For many vears there had been lying unrecognized in America a rich accumulation of folklore in the traditions, the songs, the tales, the proverbs, an.d the quaint philosophy of the plantation Negroes of the South. AVith the breaking up of the old patriarchal life and the advent of modern industrialism, this unique folklore was threatened with a speedy extinction. Doubtless it would have largely faded into oblivion, were it not for the fact that during the 'Seventies and 'Eighties there happened to be sitting at a desk in the office of the Atlanta Constitution the one man who possessed the tempermental qualifications to interpret this folklore, and the ability as a writer to mold it into literature of universal appeal. So it came to pass that this neglected store of plantation folklore was given at last to the world in a series of inimitable stories which for more than forty years have been the delight of children, and of all who are youthful in spirit, wherever the English language is spoken. -

Uncle Remus, Brer Rabbit, and Bugs Bunny

Brian T. Murphy ENG 220-CAH: Mythology and Folklore (Honors) Fall 2019 Trickster Tales: Uncle Remus, Brer Rabbit, and Bugs Bunny “Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit: Background Reading” ........................... 1 “The Wonderful Tar Baby Story” and Cognates by Joel Chandler Harris .................................................................... 3 by Julius Lester ................................................................................. 4 “The Rabbit and the Tar Wolf” (Cherokee) ..................................... 5 “Anansi and the Tar-baby” (Jamaica) .............................................. 6 “The Substitute” (Jamaica) ............................................................... 6 “The Brier Patch” by Joel Chandler Harris .................................................................... 7 by Julius Lester ................................................................................. 8 “Brer Rabbit in Africa” ............................................................................. 9 “Bugs Bunny: The Trickster, American Style” ...................................... 13 www.Brian-T-Murphy.com/Eng220.htm Background Reading (from Laura Gibbs, Mythology and Folklore of the World) Joel Chandler Harris, a journalist, a Southerner, a white man, published his first Brer Rabbit story in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper in 1879, fourteen years after the end of the Civil War. Harris had heard the Brer Rabbit stories all his life, having grown up as a poor white child in Putnam County, Georgia (his father deserted the -

The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man

Excerpted, and illustrations added, by the National Humanities Center for use in a Professional Development Seminar Library of Congress JAMES WELDON JOHNSON The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man 1912 (published anonymously) 1927, 2nd ed. (published under Johnson’s name) Excerpts: the cake walk spirituals (“Jubilee songs”) the stereotypical image of the Negro Punctuation and spelling follow the 1912 edition. 1896 Some minor wording was changed in the 1927 edition. Illustrations added; not in Autobiography. ¸ On first viewing the cake walk at an African American public ball in Jacksonville, Florida [I]t was at one of these balls that I first saw the cake-walk. There was a contest for a gold watch, to be awarded to the hotel head-waiter receiving the greatest number of votes. There was some dancing while the votes were being counted. Then the floor was cleared for the cake-walk. A half-dozen guests from some of the hotels took seats on the stage to act as judges, and twelve or fourteen couples began to walk for a “sure enough” highly decorated cake, which was in plain evidence. The spectators crowded about the space reserved for the contestants and watched them with interest and excitement. The couples did not walk around in a circle, but in a square, with the men on the inside. The fine points to be considered were the bearing of the men, the precision with which they turned the corners, the grace of the women, and the ease with which they swung around the pivots. The men walked with stately and soldierly step, and the women with considerable grace. -

Fanon As Reader of African American Folklore

Fanon as Reader of African American Folklore by Paulette Richards Independent Scholar Atlanta, Georgia, USA [email protected] Abstract This essay explores Fanon’s overt and covert uses of African American folk hero, Brer Rabbit in Black Skin White Masks by following up on Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s call for “properly contextualized readings of Fanon’s opus in relation to other germinal works of his era.” Examining Fanon’s relationship to Black American culture as distilled in the pages of Les temps modernes exposes some interesting anomalies in his identity politics vis-à-vis Black America. His manipulation of “The Malevolent Rabbit” trope identified by Bernard Wolfe creates a complex dialogue between oral and print sources which enabled him to employ rhetorical strategies derived from the folk culture of Africans in the Americas to plead his case before the white metropolitan audience even as he resisted earlier Négritude writers’ pretentions to pan- diasporic identity. Introduction In his 1991 essay, “Critical Fanonism,” Henry Louis Gates, Jr. called for “properly contextualized readings of Fanon’s opus in relation to other germinal works of his era.” 1 This study will therefore take Gates’ methodological cue and focus on Fanon’s relationship to Black American culture as distilled in the pages of Les temps modernes . Over the first ten years of its existence from 1946-56 the writers who contributed to Les temps modernes frequently offered critical analyses of contemporary American society. The combined August/September issue for 1946 was devoted exclusively to consideration of the USA, its situations, myths, and people. 126 The Journal of Pan African Studies , vol.4, no.7, November 2011 The articles in this issue include excerpts from James Weldon Johnson’s American Book of Negro Spirituals as well as extensive selections from St. -

Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings

UDC 821.111(73).09 Харис Џ. Ш. Jennifer Kilgore-Caradec* University of Caen, Normandy Catholic University of Paris, France UNCLE REMUS, HIS SONGS AND HIS SAYINGS Abstract In spite of the fact that Joel Chandler Harris was a white author from the antebellum South, his Uncle Remus stories may be credited with preserving authentic African American speech patterns of the nineteenth century. Harris had befriended a slave, George Terrell, while working on the Turner plantation as an apprentice printer shortly before the Civil War. Terrell was a father-figure to Harris, who recalled stories he had told when he created the character of Uncle Remus. The stories arise from African folklore, and make a link between African tales. Hence we find the true African roots of the contemporary Bugs Bunny.. Although the stories were sometimes used by whites to further racism, especially in a Hollywood production of 1946,and although Harris himself sometimes looked back nostalgically to the time of slavery, in fact these stories replete with trickster characters cannot be seen as anything less than African-American empowerment tales. They have rightfully been recovered by African Americans ranging from James Weldon Johnson in 1917 to jazz musicians and contemporary African American story tellers such as Diane Ferlatte. It also becomes clear that many African American writers who emphasize the oral tradition in their works may owe something to Joel Chandler Harris. Key words: Joel Chandler Harris, Brer Rabbit, Uncle Remus, eatonton, Georgia, Dialect Folk Tales, African American Culture and Heritage, M, rk Twain, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Songs from the South (1946), Alain Locke, Langston Hughes, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Diane Ferlatte, William Morris, James Weldon Johnson, eddie Vinson, Roy Buchanan, Wynton Marsalis * E-mail address: [email protected] 35 Belgrade BELLS Joel Chandler Harris first published Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings in 1880. -

Joel Chandler Harris: Aesop of the South

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Theses Theses, Dissertations & Graduate Projects 1964 Joel Chandler Harris: Aesop of the South Thomas Adams Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/etds_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Thomas, "Joel Chandler Harris: Aesop of the South" (1964). Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/etds_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations & Graduate Projects at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jnstructional Materials Cen ter \Jacksonville State Coll ege JOEL CHANDL ER HARRI S - AESOP OF THE S (·UTH by Thomas Adams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements f or the deg ree of master of science in education at the J a cksonville State College JBcks o nvilie, Alabama 1964 I ) I,• TOP IC OUT:D.iIN E I. Influ ence of his early life A. Fanily bac kgr ound B. Environmental influence of Eata ton C. Apprenticeship at Turnwold D. Influence of fri ends a n d acquaintances II. His productive years A. EffoDts in journalism B. Impact of " paragraphing" C. The Savannah days D. The Atlanta years I I I . His Works A. The Uncle Remus stories ) B. Essays and novels C. P olitical writing s D. Unpublished works IV. Various interpretations of Harris A. Julia Collier Harris B. -

Georgia Women of Achievement Honorees Name Year City Andrews

Georgia Women of Achievement Honorees Name Year City Andrews, Eliza Frances (Fanny) 2006 Washington Southern writer (1840-1931) incl 2 botany books Andrews, Ludie Clay 2018 Milledgeville 1st black registered nurse in Georgia, founder of Grady nursing school for colored nurses. Anthony, Madeleine Kiker 2003 Dahlonega community activist for Dahlonega Atkinson, Susan Cobb Milton 1996 Newnan influenced her governor-husband to fund grants for women to attend college; successfully petitioned legislature to create what would be Georgia College & St Univ at Milledgeville; appointed postmistress of Newnan by Pres TRoosevelt. Bagwell, Clarice Cross 2020 Cumming Trailblazer in Georgia education; Bagwell School of Education at KSU Bailey, Sarah Randolph 2012 Macon eductor, civic leader, GS leader Bandy, Dicksie Bradley 1993 Dalton entrepreneur - carpet industry; initiated economic revitalization of NW Georgia aftr Great Depression via homemade tufted bedspreads; philanthropist; benefactor to Cherokee Nation Barrow, Elfrida de Renne 2008 Savannah author, poet Beasley, Mathilda 2004 Savannah black Catholic nun who ran a school for black children Berry, Martha McChesney 1992 Rome educator, founder Berry College Black, Nellie Peters 1996 Atlanta social & civic leader; pushed for womens' admittance to UGA; aligned with Pres TRoosevelt re agricultural diversification & Pres Wilson re conservation. Bosomworth, Mary Musgrove 1993 Savannah cultural liaison between colonial Georgia & her Native American community Bynum, Margaret O 2007 Atlanta 1st FT consultant