Untitled MS, , N.D., Rebecca Latimer Felton Papers, UGA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agrarian-Rebel-Biogr

C. VANN WOODWARD TOM WATSON Agrarian Rebel THE BEEHIVE PRESS SAVANNAH • GEORGIA Contents I The Heritage I II Scholar and Poet IO III "Ishmael" in the Backwoods 27 IV The "New Departure" 44 V Preface to Rebellion 62 VI The Temper of the 'Eighties 7i VII Agrarian Law-making 81 VIII Henry Grady's Vision 96 IX The Rebellion of the Farmers no X The Victory of 1890 125 XI "I Mean Business" 143 XII Populism in Congress 163 XIII Race, Class, and Party 186 XIV Populism on the March 210 XV Annie Terrible 223 XVI The Silver Panacea 240 XVII The Debacle of 1896 261 XVIII Of Revolution and Revolutionists 287 XIX From Populism to Muckraking 307 XX Reform and Reaction 320 XXI "The World is Plunging Hellward" 343 XXII The Shadow of the Pope 360 XXIII The Lecherous Jew 373 XXIV Peter and the Armies of Islam 390 XXV The Tertium Quid 411 Bibliography 422 Index i V Preface to the 1973 Reissue THE reissue OF an unrevised biography thirty-five years after its original publication raises some questions about the effect that history has on historical writing as well as the effect that changing fashions of historical writing have on history written according to earlier fashions. Among the many historical events of the last three decades that have altered the perspective from which this book was writ ten, perhaps the most outstanding has been the movement for political and civil rights of the black people. All that was still in the unforeseeable future in 1938. At that time the Negro was still thoroughly disfranchised in the South, and no white South ern politician dared speak out for the political or civil rights of blacks. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Adult Education in Civil War Richmond January 1861-April 1865

ADULT EDUCATION IN CIVIL WAR RICHMOND JANUARY 1861-APRIL 1865 JOHN L. DWYER Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Adult and Continuing Education Harold W. Stubblefield, Chair Alan W. Beck Thomas C. Hunt Ronald L. McKeen Albert K. Wiswell March 19, 1997 Falls Church, Virginia Keywords: Adult Education. Richmond. Civil War Copyright 1997. John L. Dwyer ADULT EDUCATION IN CIVIL WAR RICHMOND January 1861-April 1865 by John L. Dwyer Committee Chairperson: Harold W. Stubblefield Adult and Continuing Education (ABSTRACT) This study examines adult education in Civil War Richmond from January 1861 to April 1865. Drawing on a range of sources (including newspapers, magazines, letters and diaries, reports, school catalogs, and published and unpublished personal narratives), it explores the types and availability of adult education activities and the impact that these activities had on influencing the mind, emotions, and attitudes of the residents. The analysis reveals that for four years, Richmond, the Capital of the Confederacy, endured severe hardships and tragedies of war: overcrowdedness, disease, wounded and sick soldiers, food shortages, high inflationary rates, crime, sanitation deficiencies, and weakened socio-educational institutions. Despite these deplorable conditions, the examination reveals that educative systems of organizations, groups, and individuals offered the opportunity and means for personal development and growth. The study presents and tracks the educational activities of organizations like churches, amusement centers, colleges, evening schools, military, and voluntary groups to determine the type and theme of their activities for educational purposes, such as personal development, leisure, and recreation. -

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell Collection, 1922-1991

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Mitchell, Margaret. Title: Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 265 Extent: 3.75 linear feet (8 boxes), 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and AV Masters: .5 linear feet (1 box, 1 film, 1 CLP) Abstract: Papers of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell including correspondence, photographs, audio-visual materials, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Requests to publish original Mitchell material should be directed to: GWTW Literary Rights, Two Piedmont Center, Suite 315, 3565 Piedmont Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30305. Related Materials in Other Repositories Margeret Mitchell family papers, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia and Margaret Mitchell collection, Special Collections Department, Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. Source Various sources. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Manuscript Collection No. -

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics The Georgia Historical Society offers educational materials for teachers to use as resources in the classroom. Explore this document to find highlighted materials related to Georgia and women’s history on the GHS website. In this document, explore the Georgia Historical Society’s educational materials in two sections: Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics. Both sections highlight some of the same materials that can be used for more than one classroom standard or topic. Female Historical Figures There are many women in Georgia history that the Georgia Historical Society features that can be incorporated in the classroom. Explore the readily-available resources below about female figures in Georgia history and discover how to incorporate them into lessons through the standards. Abigail Minis SS8H2 Analyze the colonial period of Georgia’s history. a. Explain the importance of the Charter of 1732, including the reasons for settlement (philanthropy, economics, and defense). c. Evaluate the role of diverse groups (Jews, Salzburgers, Highland Scots, and Malcontents) in settling Georgia during the Trustee Period. e. Give examples of the kinds of goods and services produced and traded in colonial Georgia. • What group of settlers did the Minis family belong to, and how did this contribute to the settling of Georgia in the Trustee Period? • How did Abigail Minis and her family contribute to the colony of Georgia economically? What services and goods did they supply to the market? SS8H3 Analyze the role of Georgia in the American Revolutionary Era. c. Analyze the significance of the Loyalists and Patriots as a part of Georgia’s role in the Revolutionary War; include the Battle of Kettle Creek and Siege of Savannah. -

"A Call to Honor" : Rebecca Latimer Felton and White Supremacy Open PDF in Browser

33% 4|HH||W|HHHI“WUIN}WWWMHWIlHIHI ‘l'HESIS ;,L llllllllllillllllIllllllllllllllllllllllllUllllllllllllllllll 200. O 3129 02 07415 LtfiRARY Michigan State University This is to certify that the thesis entitled "A CALL 'm m" : 113:3th TATIMER Harmon AND WHITE SUPREMACY presented by MARY A. HESS has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for __M.A._.degree in m Major professor Date __Janna.r§z_1,_1_999_ 0-7639 MS U is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Institution PLACE IN RETURN Box to remove this checkout from your record. I To AVOID PINS return on or before date due. MAY BE RECAU£D with earlier due date if requested. DATE DUE DATE DUE _ DATE DUE moo WWW“ "A CALL TO HONOR": REBECCA LATIMER FELTON AND WHITE SUPREMACY BY Mary A. Hess A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History 1999 ABSTRACT "A CALL TO HONOR": REBECCA LATIMER FELTON AND WHITE SUPREMACY BY Mary A. Hess Rebecca Latimer Felton, suffragist and reformer, was a fervent advocate of white supremacy and a believer in the use of lynching as social control. Her status as an elite white woman of the New South, the wife of a Georgia politician who served two terms in the U.S.Congress, as well as the protege of Populist leader Tom Watson, allowed her unusual access to public platforms and the press. Felton, a woman of extraordinary abilities, relished her power in Georgia politics and remained a force until her death. She was appointed as interim U.S. -

1906 Catalogue.Pdf (7.007Mb)

ERRATA. P. 8-For 1901 Samuel B. Thompson, read 1001 Samuel I?. Adams. ' P. 42—Erase Tin-man, William R. P. 52—diaries H. Smith was a member of the Class of 1818, not 1847. : P. 96-Erase star (*) before W. W. Dearing ; P. 113 Erase Cozart, S. W. ' P. 145—Erase Daniel, John. ' j P. 1GO-After Gerdine, Lynn V., read Kirkwood for Kirkville. I P. 171—After Akerman, Alfred, read Athens, (Ja., for New Flaven. ; P. 173—After Pitner, Walter 0., read m. India Colbort, and erase same ' after Pitner, Guy R., on p. 182. • P. 182-Add Potts, Paul, Atlanta, Ga. , ! CATALOGUE TRUSTEES, OFFICERS, ALUMNI AND MATRICULATES UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, AT ATHENS, GEORGIA, FROM 1785 TO 19O<». ATHENS, OA. : THF, E. D. STONK PRESS, 190G. NOTICE. In a catalogue of the alumni, with the meagre information at hand, many errors must necessarily occur. While the utmost efforts have been made to secure accuracy, the Secretary is assurer) that he has, owing to the impossibility of communicating with many of the Alumni, fallen far short of attaining his end. A copy of this catalogue will be sent to all whose addresses are known, and they and their friends are most earnestly requested to furnish information about any Alumnus which may be suitable for publication. Corrections of any errors, by any person whomsoever, are re spectfully invited. Communications may be addressed to A. L. HULL, Secretary Board of Trustees, Athens, Ga. ABBREVIATIONS. A. B., Bachelor of Arts. B. S., Bachelor of Science. B. Ph., Bachelor of Philosophy. B. A., Bachelor of Agriculture. -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

·Srevens Thomson Mason I

·- 'OCCGS REFERENCE ONL"t . ; • .-1.~~~ I . I ·srevens Thomson Mason , I Misunderstood Patriot By KENT SAGENDORPH OOES NOi CIRCULATE ~ NEW YORK ,.. ·E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY, INC. - ~ ~' ' .• .·~ . ., 1947 1,- I ' .A .. ! r__ ' GENEALOGICAL NOTES FROM JoHN T. MAsoN's family Bible, now in the Rare Book Room in the University of Michigan Library, the following is transcribed: foHN THOMSON MASON Born in r787 at Raspberry Plain, near Leesburg, Virginia. Died at Galveston, Texas, April r7th, 1850, of malaria. Age 63. ELIZABETH MOIR MASON Born 1789 at Williamsburg, Virginia. Died in New York, N. Y., on November 24, 1839. Age 50. Children of John and Elizabeth Mason: I. MARY ELIZABETH Born Dec. 19, 1809, at Raspberry Plain. Died Febru ary 8, 1822, at Lexington, Ky. Age 12. :2. STEVENS THOMSON Born Oct. 27, l8II, at Leesburg, Virginia. Died January 3rd, 1843. Age 3x. 3. ARMISTEAD T. (I) Born Lexington, Ky., July :i2, 1813. Lived 18 days. 4. ARMISTEAD T. (n) Born Lexington, Ky., Nov. 13, 1814. Lived 3 months. 5. EMILY VIRGINIA BornLex ington, Ky., October, 1815. [Miss Mason was over 93 when she died on a date which is not given in the family records.] 6. CATHERINE ARMis~ Born Owingsville, Ky., Feb. 23, 1818. Died in Detroit'"as Kai:e Mason Rowland. 7. LAURA ANN THOMPSON Born Oct. 5th, l82x. Married Col. Chilton of New York. [Date of death not recorded.] 8. THEODOSIA Born at Indian Fields, Bath Co., Ky., Dec. 6, 1822. Died at. Detroit Jan. 7th, 1834, aged II years l month. 9. CORNELIA MADISON Born June :i5th, 1825, at Lexington, Ky. -

2010 Virginia Women in History Program Honors Eight Outstanding Women Contact: Janice M

2010 Virginia Women in History Program Honors Eight Outstanding Women Contact: Janice M. Hathcock For Immediate Release 804-692-3592 A ground-breaking architect, a renowned folk artist, a patron of the arts, and a rockabilly singer known as the "female Elvis” are among eight Virginia women recognized by the Library of Virginia as part of its Virginia Women in History program. The eight being honored this year are: • Jean Miller Skipwith (1748–1826), book collector, Mecklenburg County • Kate Mason Rowland (1840–1916), historian, Richmond • Mollie Wade Holmes Adams (1881–1973), Upper Mattaponi craftsman, King William County • Queena Stovall (1888–1980), folk painter, Lynchburg • Ethel Madison Bailey Furman (1893–1976), architect, Richmond • Edythe C. Harrison (1934–), patron of the arts, Norfolk • Marian Van Landingham (1937– ), founder of the Torpedo Factory Art Center and former member of the House of Delegates, Alexandria • Janis Martin (1940–2007), rockabilly singer, Sutherlin (east of Danville) The 2010 honorees also will be celebrated at an awards ceremony hosted by May-Lily Lee of Virginia Cu rrents at the Library on Thursday, March 25 at 6:00 PM. Seating is a on first come, first seated basis. A reception will follow the program. Please call 804-692-3900 by March 22 to let us know that you will be attending. The eight also are featured on this year's handsome Virginia Women in History poster, issued in celebration of Women's History Month, and in the Library’s 2010 Virginia Women in History panel exhibition, on display in the lobby of the Library of Virginia in March. -

354 Notes NOTES· 355 the Private Civil War: Popular Thought During the Sectional Conflict (Baton Rouge, 1988)

354 Notes NOTES· 355 The Private Civil War: Popular Thought During the Sectional Conflict (Baton Rouge, 1988). 4. In the first year of its publication, the novel sold 300,000 copies and within a 11. Orville Vernon Burton, In My Father's House are Many Mansions: Family decade it had sold more than 2 million copies. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of and Community in Edgefield, South Carolina (Chapel Hill, 1985); Steven Hahn, The Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, 1988), 88-89. Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia 5. As cited in McPherson, ibid., 90. According to McPherson, Lincoln consulted Up-country, 1850-1890 (New York, 1983); J. William Harris, Plain Folk and Stowe's work, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, when he was confronting the problem of Gentry in a Slave Society: White Liberty and Black Slavery in Augusta's Hinterlands slavery in the summer of 1862 (89). (Middletown, Conn., 1985); Wayne K. Durrill, War of Another Kind: A Southern 6. Chesnut discusses Stowe's work on twenty separate occasions in her diary. Community in the Great Rebellion (New York: 1990). Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Chesnut's Civil War, C. Vann Woodward, ed. (New 12. Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the Haven and London, 1981), 880. American Civil War (New York, 1989); Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft 7. Of course the middle-class northern household was supported by the labor Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (New York, 1990). -

Georgia Power Company Has Been Serving Georgians Since the 1880S

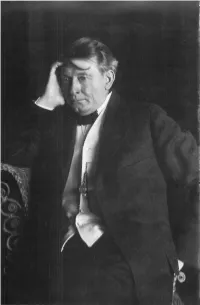

BUSINESS HISTORY PROFILE Georgia Power Company has been serving Georgians since the 1880s. From a small electric company supplying electricity primarily to Atlanta residents, Georgia Power has grown to become the state’s leading power provider. Not just a producer of electricity, Georgia Power lives up to its longtime motto “A Citizen Wherever We Serve” by creating jobs, bringing new industry to the state, and running one of the largest corporate foundations in Georgia. The people of Atlanta took the initiative to organize the first Georgia Power Company, the Georgia Electric Light Company of Atlanta (GELCA). In 1883, the company built a 940-kilowatt generating plant on Marietta and Spring Streets, installed 22 electric streetlights, and received a franchise that allowed it to provide electricity to Atlanta residents. At first, GELCA primarily provided electricity for street lighting and street Top: Henry M. Atkinson, founder of railway transportation. After Atlanta banker Henry M. Atkinson took control of the Georgia Electric Light Company. Bottom: company in 1891, GELCA expanded to include a new steam electric generating plant on Preston S. Arkwright, first president of Georgia Railway and Electric Company. Davis Street. He also shortened the company name to Georgia Electric Light Company. Left: Generators at Tallulah Falls hydroelectric plant. Although the Davis Street Plant was generating 11,000 kilowatts of power and serving about 400 customers, the demand for electricity continued to increase. Atkinson recognized this demand and decided to expand the company. He and rival Joel Hurt, a streetcar entrepreneur, competed to gain control of Atlanta’s small electric, streetcar, and steam-heat businesses.