The Atlanta Historical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

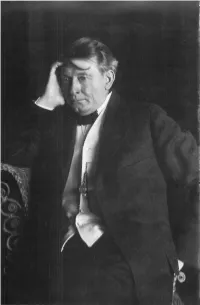

Agrarian-Rebel-Biogr

C. VANN WOODWARD TOM WATSON Agrarian Rebel THE BEEHIVE PRESS SAVANNAH • GEORGIA Contents I The Heritage I II Scholar and Poet IO III "Ishmael" in the Backwoods 27 IV The "New Departure" 44 V Preface to Rebellion 62 VI The Temper of the 'Eighties 7i VII Agrarian Law-making 81 VIII Henry Grady's Vision 96 IX The Rebellion of the Farmers no X The Victory of 1890 125 XI "I Mean Business" 143 XII Populism in Congress 163 XIII Race, Class, and Party 186 XIV Populism on the March 210 XV Annie Terrible 223 XVI The Silver Panacea 240 XVII The Debacle of 1896 261 XVIII Of Revolution and Revolutionists 287 XIX From Populism to Muckraking 307 XX Reform and Reaction 320 XXI "The World is Plunging Hellward" 343 XXII The Shadow of the Pope 360 XXIII The Lecherous Jew 373 XXIV Peter and the Armies of Islam 390 XXV The Tertium Quid 411 Bibliography 422 Index i V Preface to the 1973 Reissue THE reissue OF an unrevised biography thirty-five years after its original publication raises some questions about the effect that history has on historical writing as well as the effect that changing fashions of historical writing have on history written according to earlier fashions. Among the many historical events of the last three decades that have altered the perspective from which this book was writ ten, perhaps the most outstanding has been the movement for political and civil rights of the black people. All that was still in the unforeseeable future in 1938. At that time the Negro was still thoroughly disfranchised in the South, and no white South ern politician dared speak out for the political or civil rights of blacks. -

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

The Western Lives of American Missionary Women in China (1860-1920)

CONVERT BUT NOT CONVERTED: THE WESTERN LIVES OF AMERICAN MISSIONARY WOMEN IN CHINA (1860-1920) A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Caroline Hearn Fuchs, M.I.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 31, 2014 CONVERT BUT NOT CONVERTED: THE WESTERN LIVES OF AMERICAN MISSIONARY WOMEN IN CHINA (1860-1920) Caroline Hearn Fuchs, M.I.A. MALS Mentor: Kazuko Uchimura, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Kate Roberts Hearn was buried in a Shanghai cemetery in 1891, a short four years after her acceptance into the Women’s Missionary Service of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. In 1873, Charlotte “Lottie” Moon left for a new life in China as a single missionary woman. She served in that country for nearly 40 years, dying aboard ship on a final return voyage to the United States. Both women left their American homes expecting to convert the people of an alien land to Christianity. They also arrived in China prepared to maintain their Western rituals and comforts, which effectively separated them from the Chinese and cultivated a sense of the “Other.” In this way, missionary women came to convert, but were not converted themselves. Missionary communities, specifically missionary women, vigorously sought to maintain domestic and work lifestyles anchored in Western culture. The rise of “domesticity” in the nineteenth century gave women an influential role as a graceful redeemer, able to transform “heathens” by demonstrating civilized values of a Christian home, complete with Western elements of cleanliness, companionable marriage, and the paraphernalia of Victorian life, such as pianos in the parlor. -

Macon-Bibb County Planning & Zoning Commission

Macon-Bibb County Planning & Zoning Commission COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Community Assessment Draft – Public Review Phase February 2006 Macon-Bibb County Planning & Zoning Commissioners Theresa T. Watkins, Chariman Joni Woolf, Vice-Chairman James B. Patton Lonnie Miley Damon D. King Administrative Staff Vernon B. Ryle, III, Executive Director James P. Thomas, Director of Urban Planning Jean G. Brown, Zoning Director Dennis B. Brill, GIS/Graphics Director D. Elaine Smith, Human Resources Officer Kathryn B. Sanders, Finance Officer R. Barry Bissonette, Public Information Officers Macon-Bibb County Comprehensive Plan 2030 Prepared By: Macon-Bibb County Planning & Zoning Commission 682 Cherry Street Suite 1000 Macon, Georgia 478-751-7460 www.mbpz.org February 2006 “The opinion, findings, and conclusions in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation, State of Georgia, or the Federal Highway Administration. Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………Introduction-1 Chapter 1- General Population Overview .................................................................... 1-1 Chapter 2 - Economic Development ............................................................................ 2-1 Chapter 3 - Housing......................................................................................................... 3-1 Chapter 4 - Natural and Cultural Resources................................................................. 4-1 Chapter 5 - Community Facilities and Services........................................................... -

Vol. 32, No. 1 November 2016

Vol. 32, No. 1 November 2016 FEATURE STORY: Christian nationalism—both gaining and losing ground? There is much talk about the growth of “Christian nationalism” even as surveys and journalists report the decline of “white Christian America,” but several papers presented at the late October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Atlanta suggest that any such phenomenon is far from a monolithic or accelerating force in society. Sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Christopher Scheitle presented a paper showing that while Christian nationalism, which they define as a position linking the importance of being Christian to being American, had shown growth between 1996 and 2004, the subsequent period up to 2014 had seen decline in this ideology. Using data from the General Social Survey in 1996, 2004, and 2014, the researchers found that 30 percent of Americans held this position in 1996, while 48 percent did in 2004, but then the rate dropped back to 33 percent in 2014. They looked at other variables that seek to maintain boundaries for true Americans, such as the importance of speaking English, and did find ReligionWatch Vol. 32, No. 1 November 2016 that this sentiment followed the same episodic pattern. Whitehead and Scheitle argue that the role of patriotism and attachment to America was stronger in 2004, which was closer to 9/11, than in the earlier and later periods. Although they didn’t have data for the last two years, they speculated that these rates may be increasing again. Associated with the reports on the rise of Christian nationalism is the conflict over the role of religion in the American public square. -

The Religion Beat Gets Beat: the Rise and Fall of Stand-Alone Religion Sections in Southern Newspapers, 1983-2015

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2021 The Religion Beat Gets Beat: The Rise and Fall of Stand-alone Religion Sections in Southern Newspapers, 1983-2015 Tara Yvette Wren Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wren, Tara Yvette, "The Religion Beat Gets Beat: The Rise and Fall of Stand-alone Religion Sections in Southern Newspapers, 1983-2015" (2021). Dissertations. 1885. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1885 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELIGION BEAT GETS BEAT: THE RISE AND FALL OF STAND-ALONE RELIGION SECTIONS IN SOUTHERN NEWSPAPERS, 1983-2015 by Tara Yvette Wren A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Communication at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Vanessa Murphree, Committee Chair Dr. Christopher Campbell Dr. David Davies Dr. Cheryl Jenkins Dr. Fei Xue May 2021 COPYRIGHT BY Tara Yvette Wren 2021 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This paper explores the religious news coverage of five southern newspapers in Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Texas. The newspapers researched in this study are among those that published a stand-alone religion section. Newspapers surveyed include – The Clarion-Ledger (Mississippi), The Charlotte Observer (North Carolina), The Dallas Morning News (Texas), The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (Georgia), and The Tennessean (Tennessee). -

![Agnes Scott Alumnae Magazine [1984-1985]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4602/agnes-scott-alumnae-magazine-1984-1985-434602.webp)

Agnes Scott Alumnae Magazine [1984-1985]

iNAE m^azin: "^ #n?^ Is There Life After CoUege? AGNES SCOTT COLLEGE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE v^ %' >^*^, n^ Front Coilt; Dean julia T. Gars don her academic robe for one of the last times before she ends her 27-year ten- ure at ASC. (See page 6.) COVER PHOTO by Julie Cuhvell EDITORIAL STAFF EDITOR Sara A. Fountain ASSOCIATE EDITOR Juliette Haq3er 77 ASSISTANT EDITOR/ PHOTOGRAPHER Julie Culvvell ART DIRECTOR Marta Foutz Published by the Office of Public Affairs for Alumnae and Friends of the College. Agnes Scott College, Decatur, GA 30030 404/373-2571 Contents Spring 1984 Volume 62, Number FEATURES ARTIST BRINGS THE MOUNTAIN HOME hdieCidudi I Agnes Scott art professor Terry McGehee reflects on how her trek in the Himalayas influenced her art. IS THERE LIFE AFTER COLLEGE? Bets_'v Fancher 6 Dean Julia T Gary takes early retirement to pursue a second career as a Methodist minister. 100 YEARS. .. Bt'ts>- ¥a^^c\^er 14 John O. Hint reminisces about his life and his years at Agnes Scott. DANCE FOLK, DANCE ART DANCE, DARLING, DANCE! Julie Culudl 16 Dance historian and professor Marylin Darling studies the revival and origin of folk dance. PROHLE OF A PLAYWRIGHT Betsy Fancher 18 Pulitzer Prize-winning alumna Marsha Norman talks about theatre today and her plays. "THE BEAR" Julie Culwell 22 Agnes Scott's neo-gothic architecture becomes the back- drop for a Hollywood movie on the life of Alabama coach Paul "Bear" Bryant. LESTWEFORGET BetsyFancher 28 A fond look at the pompous Edwardian figure who con- tinues to serve the College long past his retirement. -

Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report)

MTA - Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report) *Last Name *First Name Middle *Title *Group School Name Highest Degree Prior Work Experience Initial O'Brien James J Mgr. Maint. Contract Admin. Managerial UNKNOWN UNKNOWN MTA Agency Berani Alban Supervising Engr Electrical Managerial CUNY City College Master of Engineering Self Employed Moravec Eva M Assistant General Counsel Professional Pace University White Plains Juris Doctor Dept. of Finance OATH Angel Nichola O AVPCenBusDisTolUnit Managerial NYU Stern School of Business Master of Mechanical Engi MTA Agency Khuu Howard N Assistant Controller Managerial Baruch College Master of Business Admin Home Box Office Reis Sergio Director Ops. Tolls & Fac. Sys Managerial Long Island University Bachelor of Science Tag Americas LLC Jacobs Daniel M Sr Dir Plan Inno&Pol Ana Managerial Rutgers University Master of Engineering MTA Agency Wilkins Alphonso Senior Safety Engineer Professional High School Diploma EnviroMed Services Inc. Walker Kellie Labor Counsel Professional Boston University Law Juris Doctor NYC Department of Education Mondal Mohammad S Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Foreign - Non US College/Unive Bachelor Civil Engineerin Department of Buildings Friman Paul Exec Asst General Counsel Professional New York University Juris Doctor NYS Supreme Court NY Prasad Indira G Sr Project Manager TSMS Professional Stevens Institute of Technolog Master of Science Mitsui O.S.K. NY Li Bin Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Florida International Univ Doctor of Philosophy -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

October 2019 Issue

1150 Peachtree Street, N.E., Atlanta, GA 30309 Telephone 404-870-8833 Website: www.atlwc.org Editor: Billie Harris October 2019 Issue PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Well, it is finally feeling like fall at times. The weather has been won- derful for walking and outside activities. I hope all of you have had an Membership………..….3-5 opportunity to enjoy. After summer, it is sometimes difficult to get International…...….…....6 back on schedule. The Fall 2019 Club Woman Magazine gave some tips on pitfalls for missing a deadline. Some of the pitfalls include: 1) Not Home Life……..…………..6 making a list so you can prioritize; 2) Multitasking is less productive Public Issues…… ……..6-7 than focusing on one task. Our brain is not equipped to perform two Conservation…………..7-8 tasks at a time; and 3) Time management. Not knowing how much time the task will take makes it is difficult to manage time to prioritize. ESO Book Club…………..9 Good points to consider. For members who prepare reports, it is time Women’s History…..10-11 to put reporting on your list and begin a draft report. This means of course that you will have to do multitasking since you are continuing Arts…………………………..11 with activities for CSPs, committees and offices. All members of the AWC are volunteers and provide services to indi- viduals and groups. In addition, members that are elected or appoint- ed to positions are accountable to provide services designated by their position description. Volunteering is different from paid positions in companies since there is no pay increase pending; there is just the sat- isfaction of the advocacy efforts and the differences made in lives of individuals and groups. -

Genealogy in Georgia

On our front cover Vintage scrapbook with bird on cover, from the Charles D. Switzer Public Library collection Accordion belonging to Graham Washington Jackson Sr., who played during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s funeral procession, from the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History collection Leather-bound and hand- lettered Catholic Liturgy choral book (Spain, 1580), courtesy of the Brunswick- Glynn County Library World War II bomber jacket, from the Ellen Payne Odom Genealogy Library collection Original photos of the first Oglethorpe County bookmobile and of Athens resident Mrs. Julius Y. (May Erwin) Talmadge with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library Heritage Room On our back cover (all from the Ellen Payne Odom Genealogy Library) Hand-carved sign featuring shared motto of several Highland clans, including Clan Macpherson, Clan Mackintosh and others Scrapbook with mother- of-pearl inlay cover Vintage copy of Burke’s Landed Gentry, opened to reveal crest of the Smith-Masters family of Camer (Kent), Great Britain We invite you to explore your genealogy, history and culture at Georgia’s public libraries! As family heritage and genealogy tourism grows more popular throughout the United States, it is our pleasure to spotlight several vital destinations found among Georgia’s public libraries. Researchers, students and teachers, as well as professional and amateur historians and genealogists, are certain to find unique and varied treasures in our distinctive and carefully curated collections. As you visit the libraries and history rooms spotlighted in this brochure, you will find much more than books; many of our libraries collect museum-quality art and artifacts that highlight the cultural history of Georgia and its residents.