Myanmar 1948 2017 to Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

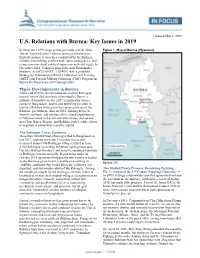

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Report (The UK Government's Response to the Myanmar Crisis)

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The UK Government’s Response to the Myanmar Crisis Fourth Report of Session 2021–22 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 July 2021 HC 203 Published on 16 July 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Tom Tugendhat MP (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) (Chair) Chris Bryant MP (Labour, Rhondda) Neil Coyle MP (Labour, Bermondsey and Old Southwark) Alicia Kearns MP (Conservative, Rutland and Melton) Stewart Malcolm McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow South) Andrew Rosindell MP (Conservative, Romford) Bob Seely MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Henry Smith MP (Conservative, Crawley) Royston Smith MP (Conservative, Southampton, Itchen) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Claudia Webbe MP (Independent, Leicester East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. -

Yangon Region Gov't, HK-Taiwan Consortium Ink Industrial Zone Deal

Business Yangon Region Gov’t, HK-Taiwan Consortium Ink Industrial Zone Deal Yangon Region Minister for Planning and Finance U Myint Thaung delivers the opening speech at a press conference at the Yangon Investment Forum 2019. / The Global New Light of Myanmar By THE IRRAWADDY 29 April 2019 YANGON—The Yangon regional government will sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with a consortium of Hong Kong and Taiwan companies next month to develop an international-standard industrial zone in Htantabin Township in the west of the commercial capital. Worth an estimated US$500 million (761.2 billion kyats) the Htantabin Industrial Zone will be implemented on more than 1,000 acres and is expected to create more than 150,000 job opportunities, said Naw Pan Thinzar Myo, Yangon Region Karen ethnic affairs minister, at a press conference on Friday. The regional government and the Hong Kong-Taiwan consortium, Golden Myanmar Investment Co., are scheduled to sign the MoU at the 2nd Yangon Investment Fair on May 10, which will showcase about 80 projects across Yangon Region in an effort to drum up local and foreign investment. It is expected to take about nine years to fully implement the Htantabin Industrial Zone. The MoU is the first to be implemented among 11 industrial zones planned by the Yangon regional government in undeveloped areas on the outskirts of Yangon. A map of the Htantabin Industrial Zone / Invest Myanmar Summit website At the country’s first Investment Fair in late January, the Yangon government showcased planned international-standard industrial zones in 11 townships: Kungyangon, Kawhmu, Twantay, Thingyan, Kyauktan, Khayan, Thongwa, Taikkyi, Hmawbi, Hlegu and Htantabin. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Updated May 17, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Summary Despite a campaign pledge that they “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners,” Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some political prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for alleged violations of Burmese laws. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of April 2019. During its three years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma’s political prisoners on six occasions. Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners. On May 23, 2017, former President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 89 political prisoners. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners. In April and May 2019, he pardoned more than 23,000 prisoners, of which the AAPP(B) considered 20 as political prisoners. Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma’s laws to suppress the opinions of its political opponents and restrict press freedoms. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57