Professional Amnesia: a Suitable Case for Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography BOOKS Archambault, R. D. (ed.), Philosophical Ana(ysis and Education, London, 1965. Armytage, W. H. G., Heavens Below, London, 1961. Arnold-Brown, A., Unfolding of Character: the impact of Gordonstoun, London, 1962. Badley, J. H., Memories and Reflections, London, 1955. Bedales: a pioneer School, London, 1923. A Schoolmaster's Testament, Oxford, 1937. Bazeley, E. T., Homer Lane and the Little Commonwealth, London, 1928 and 1948. Besant, Annie, Gospel of Atheism, 1877. Blavatsky, Helena, The Secret Doctrine, London, 1931. Blewitt, T. (ed.), The Modern Schools Handbook, London, 1934. Bonham-Carter, V., Darlington Hall, London, 1958. History of Bootham School, I82j-I92J, London, 1926. Boyd, W., and Rawson, W., The Story of the New Education, London, 1965. Brath, S. de, The Foundations of Success: a Plea for a Rational Education, 1896. British Economy: Kry Statistics I900-I964, Cambridge. Carpenter, E., Towards Democrary, 1883 and 1902. Child, H. A. T. (ed.), The Independent Progressive School, London, 1962. Cook, E. T., and Wedderburn, A., The Works of John Ruskin, London, 1905. Cremin, L.A., Transformation of the School, New York, 1961. Cresswell, D., Margaret McMillan: a Memoir, London, 1948. Culverwell, E. P., Montessori Principles and Practice, London, 1913. Curry, W. B., The School, London, 1934. Education for Sanity, London, 1947· Demolins, E., Anglo-Saxon Superiority: to what is it due?, London, 1898. L' Education nouvelle, Librairie de Paris, 1901. Dewey, Evelyn, The Dalton Laboratory Plan, London, 1924. Dewey, J., The School and Society, New York, 1899· My Pedagogic Creed, New York, 1897. The Child and the Curriculum, New York, 1902. Moral Principles in Education, New York, 1909. -

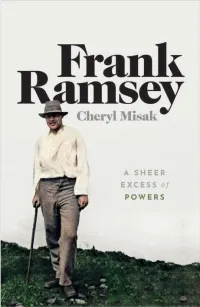

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Catz-The-Year-2010.Pdf

Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page c The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2010 Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page d Master and Fellows 2010 MASTER RobertALeese, MA (PhD Durh) Marc Lackenby, MA (PhD Camb) Peter P Edwards, MA (BSc, PhD Christoph Reisinger, (Dipl Linz, Professor Roger W Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Pure Mathematics Salf), FRS Dr phil Heidelberg) Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, FRAeS Mathematics Leathersellers’ Fellow Professor of Inorganic Chemistry Tutor in Mathematics Director of the Smith Institute Professor of Mathematics (Leave M10-T11) FELLOWS Timothy J Bayne, (BA Otago, Sudhir Anand, MA, DPhil Louise L Fawcett, MA, DPhil (BA Marc E Mulholland, MA (BA, Patrick S Grant, MA, DPhil (BEng PhD Arizona) Tutor in Economics Lond) MA, PhD Belf) Nott) FREng Tutor in Philosophy Harold Hindley Fellow Tutor in Politics Wolfson Fellow Cookson Professor of Materials Professor of Quantitative Wilfrid Knapp Fellow Tutor in History Robert E Mabro, CBE, MA (BEng Economic Analysis (Leave M10-T11) Dean Justine N Pila, MA (BA, LLB, PhD Alexandria, MSc Lond) (Leave M10) Melb) Fellow by Special Election Susan C Cooper, MA (BA Collby Gavin Lowe, MA, MSc, DPhil Tutor in Law Richard J Parish, MA, DPhil (BA Maine, PhD California) Tutor in Computer Science College Counsel Kirsten E Shepherd-Barr, MA, Newc) Professor of Experimental Physics Professor of Computer Science DPhil (Grunnfag Oslo, BA Yale) Tutor in French (Leave T11) Bart B van Es, (BA, MPhil, PhD Tutor in English Philip -

Preparatory Schools 2018 a Guide to 1500 Independent Preparatory and Junior Schools in the United Kingdom 1 Providing Education for 2 ⁄2 to 13-Year-Olds

JOHN CATT’S Preparatory Schools 2018 A guide to 1500 independent preparatory and junior schools in the United Kingdom 1 providing education for 2 ⁄2 to 13-year-olds 21ST EDITION The UK’s Leading Supplier of School and Specialist Minibuses • Fully Type Approved 9 - 17 Seat Choose with confidence, our knowledge and School Minibuses support make the difference • All The Leading Manufacturers • D1 and B Licence Driver Options 01202 827678 • New Euro Six Engines, Low Emission redkite-minibuses.com Zone (LEZ) Compliant [email protected] • Finance Option To Suit all Budgets • Nationwide Service and Support FORD PEUGEOT VAUXHALL APPROVED SUPPLIERS JOHN CATT’S Preparatory Schools 2018 21st Edition Editor: Jonathan Barnes Published in 2018 by John Catt Educational Ltd, 12 Deben Mill Business Centre, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 1BL UK Tel: 01394 389850 Fax: 01394 386893 Email: [email protected] Website: www.johncatt.com © 2017 John Catt Educational Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Database right John Catt Educational Limited (maker). Extraction or reuse of the contents of this publication other than for private non-commercial purposes expressly permitted by law is strictly prohibited. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors, and are not necessarily those of the publishers or the sponsors. We cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Designed and typeset by John Catt Educational Limited. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Mcenroe, Francis John (1986) Psychoanalysis and Early Education

McEnroe, Francis John (1986) Psychoanalysis and early education : a study of the educational ideas of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), Anna Freud (1895-1982), Melanie Klein (1882-1960), and Susan Isaacs (1885- 1948). PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2094/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EARLY EDUCATION :A STUDY OF THE EDUCATIONAL IDEAS OF SIGMUND FREUD (1856-1939), ANNA FREUD (1895-1982), MELANIE KLEIN (1882-1960), AND SUSAN ISAACS (1885-1948). Submitted by Francis John NIcEnroe, M. A., M. Ed., for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Education. Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow. September, 1986. 11 But there is one topic which I cannot pass over so easily - not, however, because I understand particularly much about it or have contributed very much to it. Quite the contrary: I have scarcely concerned myself with it at all. I must mention it because it is so exceedingly important, so rich in hopes for the future, perhaps the most important of all the activities of analysis. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of drama in education 1902-1944: an account of the developing awareness of the educational possibilities of drama with particular reference to English schools Cox, Timothy James How to cite: Cox, Timothy James (1970) The development of drama in education 1902-1944: an account of the developing awareness of the educational possibilities of drama with particular reference to English schools, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10061/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 TLE DEVELOPMENT OF DRAMA IN Ei)U CATION 1902-1944 An account of the developing awareness of the educational possibilities of drama with particular reference to English schools. A TNESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF DURIiAM by Timothy James Cox The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Dora and Bertrand Russell and Beacon Hill School

DORA AND BERTRAND RUSSELL AND BEACON HILL SCHOOL D G History / Carleton U. Ottawa, , Canada _@. This essay examines Beacon Hill School, founded in by Bertrand and Dora Russell. I consider the roles of the school’s two founders and the significance of the school as an educational and social experiment, situating its history in the context of the development of progressive education and of modernist ideas about marriage and childrearing in the first half of the twentieth century. Although Bertrand Russell played a crucial role in founding Beacon Hill, it was primarily Dora Russell’s project, and it was exclusively hers from until the school ceased to exist in . or more than a century, progressive ideas about children, child- rearing and education have gone in and out of favour. In the s a “free school” movement flourished in North America and F ff in Britain, and in Britain progressive ideas had a significant e ect on the State school system. Today, in contrast, progressive ideas are largely out Luminaries of the Free School movement of the s and s included A. S. Neill, John Holt, Jonathan Kozol and Ivan Illich. On the movement in Britain, see David Gribble, Real Education: Varieties of Freedom (Bristol: Libertarian Education, ). For the .. see Ron Miller, Free Schools, Free People: Education and Democracy After the s (Albany, ..: State U. of New York P., ). Colin Ward, for many years editor of Anarchy, has written much insightful and inspiring work on freedom and education in a British context, and fostered discussion in the s through Anarchy.His russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies n.s. -

Book Reviews

FORUM Volume 52, Number 3, 2010 www.wwwords.co.uk/FORUM Book Reviews The Pendulum Swings: transforming school reform BERNARD BARKER, 2010 Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books 220 pages, £18.99 (paperback), ISBN 978-1-85856-468-5 This is a provocative and challenging book by a teacher and educationist whose work I have always much admired. I was inspired by the concept of a ‘common education’ that he articulated in his 1986 book Rescuing the Comprehensive Experience, and I was glad that he went on to develop his views on the aims of a ‘comprehensive’ education in a chapter he wrote for the first Bedford Way Paper I ever edited for the Institute of Education, Redefining the Comprehensive Experience, published a year later. In this new book, he uses a fascinating combination of statistical data, detailed case-studies and personal anecdotes to mount a devastating critique of government education policy since 1988 and to make the case for a set of imaginative ideas for transforming school reform. All this makes for exciting reading; but I find that I part company with Bernard Barker on two issues: the first concerns his views on the limited role that schools can play in effecting social change and enhancing life-chances; and the second relates to his somewhat optimistic contention that we are about to see a rejection of the dehumanising ideas that have dominated education policy- making for at least the last 30 years. The central thesis of the book is that the following five illusory beliefs have underpinned both Conservative and New Labour school reform policies since 1988: 1. -

HPS: Annual Report 2002-03

Contents The Department Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 Staff and affiliates .................................................................................................................... 3 Visitors and students ................................................................................................................ 4 Comings and goings................................................................................................................. 5 Roles and responsibilities......................................................................................................... 6 Prizes, projects and honours..................................................................................................... 7 Seminars and special lectures...................................................................................................8 Students Student statistics..................................................................................................................... 10 Part II dissertation titles ......................................................................................................... 11 Part II primary sources essay titles......................................................................................... 12 MPhil essay and dissertation titles ......................................................................................... 15 PhD theses............................................................................................................................. -

Comparisons in Early Years Education: History, Fact, and Fiction. ISSN ISSN-1524-5039 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 19P.; in ECRP Volume 2, Number 1; See PS 028 521

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 852 PS 028 524 AUTHOR Drummond, Mary Jane TITLE Comparisons in Early Years Education: History, Fact, and Fiction. ISSN ISSN-1524-5039 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 19p.; In ECRP Volume 2, Number 1; see PS 028 521. This is an edited version of the fourth W.A.L. Blyth Lecture, given at the University of Warwick, March 10, 1998. It was first published as an Occasional Paper by the Centre for Research in Elementary & Primary Education, 1999. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v2n1/print/drummond.html. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) -- Opinion Papers (120) JOURNAL CIT Early Childhood Research & Practice; v2 n1 Spr 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Early Childhood Education; Educational Environment; Educational History; *Educational Innovation; *Educational Philosophy; Educational Principles; Foreign Countries; Imagination; Teacher Student Relationship; *Teaching Methods; Values IDENTIFIERS Alcott (Bronson); Alcott (Louisa May); England; *Isaacs (Susan); Malting House School (England) ABSTRACT This article discusses the characteristics of three schools and considers what lessons modern educators might learn from them. The first school described is the Malting House school, where Susan Isaacs taught for several years. The Malting House school, which existed from 1924 to 1929 in Cambridge, England, teaches the lesson of looking, with attention, at everything that children do. The second school discussed is a present-day primary classroom in Hertfordshire, England, taught by Annabelle Dixon. This classroom demonstrates the relationship between an educator's core values and her pedagogical practices. The third school discussed is Louisa May Alcott's fictional school, Plumfield. -

A British Childhood? Some Historical on Reflections Continuities and Discontinuities in the Culture of Anglophone Childhood

A British Childhood? Some Historical Reflections on Continuities and Discontinuities in the Culture of Anglophone Childhood Anglophone of Culture the in Discontinuities and Continuities Reflections on Historical Some Childhood? British A A British Childhood? Some Historical Reflections on Continuities and Discontinuities in the Culture of Anglophone Childhood • Pam Jarvis Edited by Pam Jarvis Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Genealogy www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy A British Childhood? Some Historical Reflections on Continuities and Discontinuities in the Culture of Anglophone Childhood A British Childhood? Some Historical Reflections on Continuities and Discontinuities in the Culture of Anglophone Childhood Special Issue Editor Pam Jarvis MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Pam Jarvis Leeds Trinity University UK Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Genealogy (ISSN 2313-5778) in 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy/special issues/ britishchildhood) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-934-6 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-935-3 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Pam Jarvis. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications.