Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography BOOKS Archambault, R. D. (ed.), Philosophical Ana(ysis and Education, London, 1965. Armytage, W. H. G., Heavens Below, London, 1961. Arnold-Brown, A., Unfolding of Character: the impact of Gordonstoun, London, 1962. Badley, J. H., Memories and Reflections, London, 1955. Bedales: a pioneer School, London, 1923. A Schoolmaster's Testament, Oxford, 1937. Bazeley, E. T., Homer Lane and the Little Commonwealth, London, 1928 and 1948. Besant, Annie, Gospel of Atheism, 1877. Blavatsky, Helena, The Secret Doctrine, London, 1931. Blewitt, T. (ed.), The Modern Schools Handbook, London, 1934. Bonham-Carter, V., Darlington Hall, London, 1958. History of Bootham School, I82j-I92J, London, 1926. Boyd, W., and Rawson, W., The Story of the New Education, London, 1965. Brath, S. de, The Foundations of Success: a Plea for a Rational Education, 1896. British Economy: Kry Statistics I900-I964, Cambridge. Carpenter, E., Towards Democrary, 1883 and 1902. Child, H. A. T. (ed.), The Independent Progressive School, London, 1962. Cook, E. T., and Wedderburn, A., The Works of John Ruskin, London, 1905. Cremin, L.A., Transformation of the School, New York, 1961. Cresswell, D., Margaret McMillan: a Memoir, London, 1948. Culverwell, E. P., Montessori Principles and Practice, London, 1913. Curry, W. B., The School, London, 1934. Education for Sanity, London, 1947· Demolins, E., Anglo-Saxon Superiority: to what is it due?, London, 1898. L' Education nouvelle, Librairie de Paris, 1901. Dewey, Evelyn, The Dalton Laboratory Plan, London, 1924. Dewey, J., The School and Society, New York, 1899· My Pedagogic Creed, New York, 1897. The Child and the Curriculum, New York, 1902. Moral Principles in Education, New York, 1909. -

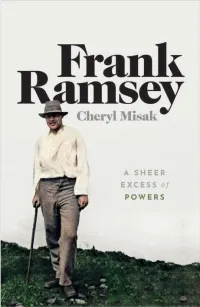

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Catz-The-Year-2010.Pdf

Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page c The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2010 Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page d Master and Fellows 2010 MASTER RobertALeese, MA (PhD Durh) Marc Lackenby, MA (PhD Camb) Peter P Edwards, MA (BSc, PhD Christoph Reisinger, (Dipl Linz, Professor Roger W Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Pure Mathematics Salf), FRS Dr phil Heidelberg) Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, FRAeS Mathematics Leathersellers’ Fellow Professor of Inorganic Chemistry Tutor in Mathematics Director of the Smith Institute Professor of Mathematics (Leave M10-T11) FELLOWS Timothy J Bayne, (BA Otago, Sudhir Anand, MA, DPhil Louise L Fawcett, MA, DPhil (BA Marc E Mulholland, MA (BA, Patrick S Grant, MA, DPhil (BEng PhD Arizona) Tutor in Economics Lond) MA, PhD Belf) Nott) FREng Tutor in Philosophy Harold Hindley Fellow Tutor in Politics Wolfson Fellow Cookson Professor of Materials Professor of Quantitative Wilfrid Knapp Fellow Tutor in History Robert E Mabro, CBE, MA (BEng Economic Analysis (Leave M10-T11) Dean Justine N Pila, MA (BA, LLB, PhD Alexandria, MSc Lond) (Leave M10) Melb) Fellow by Special Election Susan C Cooper, MA (BA Collby Gavin Lowe, MA, MSc, DPhil Tutor in Law Richard J Parish, MA, DPhil (BA Maine, PhD California) Tutor in Computer Science College Counsel Kirsten E Shepherd-Barr, MA, Newc) Professor of Experimental Physics Professor of Computer Science DPhil (Grunnfag Oslo, BA Yale) Tutor in French (Leave T11) Bart B van Es, (BA, MPhil, PhD Tutor in English Philip -

Preparatory Schools 2018 a Guide to 1500 Independent Preparatory and Junior Schools in the United Kingdom 1 Providing Education for 2 ⁄2 to 13-Year-Olds

JOHN CATT’S Preparatory Schools 2018 A guide to 1500 independent preparatory and junior schools in the United Kingdom 1 providing education for 2 ⁄2 to 13-year-olds 21ST EDITION The UK’s Leading Supplier of School and Specialist Minibuses • Fully Type Approved 9 - 17 Seat Choose with confidence, our knowledge and School Minibuses support make the difference • All The Leading Manufacturers • D1 and B Licence Driver Options 01202 827678 • New Euro Six Engines, Low Emission redkite-minibuses.com Zone (LEZ) Compliant [email protected] • Finance Option To Suit all Budgets • Nationwide Service and Support FORD PEUGEOT VAUXHALL APPROVED SUPPLIERS JOHN CATT’S Preparatory Schools 2018 21st Edition Editor: Jonathan Barnes Published in 2018 by John Catt Educational Ltd, 12 Deben Mill Business Centre, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 1BL UK Tel: 01394 389850 Fax: 01394 386893 Email: [email protected] Website: www.johncatt.com © 2017 John Catt Educational Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Database right John Catt Educational Limited (maker). Extraction or reuse of the contents of this publication other than for private non-commercial purposes expressly permitted by law is strictly prohibited. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors, and are not necessarily those of the publishers or the sponsors. We cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Designed and typeset by John Catt Educational Limited. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Dora and Bertrand Russell and Beacon Hill School

DORA AND BERTRAND RUSSELL AND BEACON HILL SCHOOL D G History / Carleton U. Ottawa, , Canada _@. This essay examines Beacon Hill School, founded in by Bertrand and Dora Russell. I consider the roles of the school’s two founders and the significance of the school as an educational and social experiment, situating its history in the context of the development of progressive education and of modernist ideas about marriage and childrearing in the first half of the twentieth century. Although Bertrand Russell played a crucial role in founding Beacon Hill, it was primarily Dora Russell’s project, and it was exclusively hers from until the school ceased to exist in . or more than a century, progressive ideas about children, child- rearing and education have gone in and out of favour. In the s a “free school” movement flourished in North America and F ff in Britain, and in Britain progressive ideas had a significant e ect on the State school system. Today, in contrast, progressive ideas are largely out Luminaries of the Free School movement of the s and s included A. S. Neill, John Holt, Jonathan Kozol and Ivan Illich. On the movement in Britain, see David Gribble, Real Education: Varieties of Freedom (Bristol: Libertarian Education, ). For the .. see Ron Miller, Free Schools, Free People: Education and Democracy After the s (Albany, ..: State U. of New York P., ). Colin Ward, for many years editor of Anarchy, has written much insightful and inspiring work on freedom and education in a British context, and fostered discussion in the s through Anarchy.His russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies n.s. -

HPS: Annual Report 2002-03

Contents The Department Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 Staff and affiliates .................................................................................................................... 3 Visitors and students ................................................................................................................ 4 Comings and goings................................................................................................................. 5 Roles and responsibilities......................................................................................................... 6 Prizes, projects and honours..................................................................................................... 7 Seminars and special lectures...................................................................................................8 Students Student statistics..................................................................................................................... 10 Part II dissertation titles ......................................................................................................... 11 Part II primary sources essay titles......................................................................................... 12 MPhil essay and dissertation titles ......................................................................................... 15 PhD theses............................................................................................................................. -

Comparisons in Early Years Education: History, Fact, and Fiction. ISSN ISSN-1524-5039 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 19P.; in ECRP Volume 2, Number 1; See PS 028 521

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 852 PS 028 524 AUTHOR Drummond, Mary Jane TITLE Comparisons in Early Years Education: History, Fact, and Fiction. ISSN ISSN-1524-5039 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 19p.; In ECRP Volume 2, Number 1; see PS 028 521. This is an edited version of the fourth W.A.L. Blyth Lecture, given at the University of Warwick, March 10, 1998. It was first published as an Occasional Paper by the Centre for Research in Elementary & Primary Education, 1999. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v2n1/print/drummond.html. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) -- Opinion Papers (120) JOURNAL CIT Early Childhood Research & Practice; v2 n1 Spr 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Early Childhood Education; Educational Environment; Educational History; *Educational Innovation; *Educational Philosophy; Educational Principles; Foreign Countries; Imagination; Teacher Student Relationship; *Teaching Methods; Values IDENTIFIERS Alcott (Bronson); Alcott (Louisa May); England; *Isaacs (Susan); Malting House School (England) ABSTRACT This article discusses the characteristics of three schools and considers what lessons modern educators might learn from them. The first school described is the Malting House school, where Susan Isaacs taught for several years. The Malting House school, which existed from 1924 to 1929 in Cambridge, England, teaches the lesson of looking, with attention, at everything that children do. The second school discussed is a present-day primary classroom in Hertfordshire, England, taught by Annabelle Dixon. This classroom demonstrates the relationship between an educator's core values and her pedagogical practices. The third school discussed is Louisa May Alcott's fictional school, Plumfield. -

The Great Educators Doctrines of the Great Educators

Doctrines of the Great Educators Doctrines of the Great Educators Robert R. Rusk and J ames Scotland FIFTH EDITION St. Martin's Press New York © R.R. Rusk 1965, 1969 © New material, James Scotland 1979 All rights reserved. For information, write: St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Printed in Great Britain Fifth edition first published in the United States of America in 1979 Reprinted 1987 ISBN 978-0-333-23221-7 ISBN 978-1-349-16075-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-16075-4 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Rusk, Robert Robertson, 1879-1972. Doctrines of the great educators. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Education-History 2. Educators I. Scotland, James, joint author. II. Title LA13.R85 1979 370.1 78-12874 ISBN 978-0-312-21491-3 ISBN 978-0-312-21492-0 pbk. Contents Preface vii 1 'The Great Educators' 1 2 Plato 7 3 Quintilian 35 4 Loyola 46 5 Comenius 62 6 Locke 80 7 Rousseau 100 8 Pestalozzi 136 9 Herbart 155 10 Froebel 178 11 Montessori 193 12 Dewey 215 13 The Twentieth Century 233 Notes and References 247 Bibliography 293 Index 303 Preface to the Fifth Edition Dr Robert Rusk died in 1972, at the age of ninety-three, his energy undimmed. This book went through four editions and seventeen impressions during his lifetime, and it has been reprinted three times since his death. It is a classic of educational exposition. For this new edition I have made some alterations, omissions and additions. -

Professional Amnesia: a Suitable Case for Treatment

FORUM, Volume 47, Number 2 & 3, 2005 Professional Amnesia: a suitable case for treatment MARY JANE DRUMMOND ABSTRACT Early Years educators have always had a particularly secure feel for what lies at the heart of vibrant education, for ‘a principled understanding of learning’. Here Mary Jane Drummond reminds the reader, not only that professional knowledge exists outside ring binders, but that, prior to their emergence, we did know some very important things we would do well to return to. In reconnecting to the richness and depth of twentieth-century pioneers she reminds the reader how things might yet be. All the writers she cites emphasise that children’s ‘most urgent need is freedom to grow and think,’ an insight that it as is true for teachers as it is for children: the time is ripe for some critical remembering. The trouble started back in 1987. Without invoking a golden age, or glorifying the mythical Plowden years, my argument is that in the years before the Education Reform Act of 1988, by and large, teachers did their own thinking, turning to a variety of sources to enrich their understanding and help them make a case for their principled pedagogical decisions. But soon after the arrival of the DES National Curriculum consultation document, and the opening of the flood-gates to a never-ending stream of official publications, the first signs of professional amnesia appeared in our midst. Slowly but surely the early years community, and our colleagues higher up the primary school, began to act as if professional knowledge were only to be found in ring folders, of all degrees of glossiness; these were soon supplemented by training packs with videos and all manner of other pronouncements from authoritative bodies. -

Secondary & Primary School Names

Primary & Secondary School Names Thank you to all of the brave survivors who are sharing their testimonies with us. Author: Everyone’s Invited England A Abberley Hall School - Worcestershire, England AKS Lytham - Lytham St Annes, England Allestree Woodlands School - Derby, England Abbey College - Ramsey, England Albany Comprehensive School - Bell Lane, Enfield, Alleyne's Academy - Staffordshire, England England Abbey Gate College - Saighton, Cheshire, England Alleyn's School - Dulwich, London, England Alcester Grammar School - Warwickshire, England Abbey Grange Church of England Academy - Leeds, Alpington Primary School - Norfolk, England England Aldenham School - Hertfordshire, England Alsager High School - Cheshire, England Abbey School - Faversham, Kent, England Alderbrook School - Solihull, England Alsop High School - Liverpool, England Abbeyfield School - Chippenham, England Alderley Edge School - Cheshire, England Alton College (now Alton Campus) - Hampshire, Abbot Beyne School - Burton Upon Trent, Alderman Cape Secondary Modern School - England Staffordshire, England Durham, England Alton Park School - Clacton On Sea, Essex, England Abingdon and Witney College - Abingdon, Oxon, Aldridge School - West Midlands, England Alton School - Hampshire, England England Aldwark Manor School (now closed) - North Altrincham Grammar School For Boys - Greater Abingdon Boys School - Oxfordshire, England Yorkshire, England Manchester, England Abingdon Prep School - Oxfordshire, England Aldwickbury School - Hertfordshire, England Altrincham Grammar -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Da es bislang keine brauchbare Literaturliste zum Thema Kinderrepubliken gibt, wurde das Literaturverzeichnis bewußt umfangreich angelegt und ent hält nicht nur die zitierte Literatur, sondern auch am Rande interessanten Titel sowie solche, die zu nicht in dieser Arbeit enthaltenen, aber ursprüng• lich geplanten und begonnenen Kapiteln gehören. Generell wurde nach Autoren- oder Herausgebernamen sortiert, Namens bestandteile wie von, van, de etc. wurden generell an den Vomamen ange hängt. Werke ohne Autor oder Herausgeber sind unter ihrem Titel einsor tiert. Im Zweifelsfall sind sie erkennbar am fehlenden Doppelpunkt hinter dem eingeklammerten Erscheinungsjahr. Bei der Zeitschriftenzitation folgt auf Autor, Aufsatztitel und Zeitschrif tentitel teilweise in Klammem der Erscheinungsort, danach folgen Band nummer oder Jahrgangsnummer, Punkt, Erscheinungsjahr, Komma, Heftnummer oder Erscheinungsdatum, Doppelpunkt, Seitenzahlen. Die Trennzeichen (Punkt, Komma, Doppelpunkt) stehen auch dann, wenn die Angabe dazwischen fehlt. Beispiel: Abbott, Lyman (1908): A Republic in the Republic. In: Outlook (New Y ork) 88.1908,: 350-354. Erwähnenswert ist noch, daß die 1925/26 von Alice und Otto Rühle in Dresden herausgegebene Zeitschrift Das Proletarische Kind nicht identisch ist mit der von Edwin Hoemle in Berlin herausgegebenen gleichnamigen Zeitschrift (Untertitel: Mitteilungsblatt für Leiter und Freunde kommunisti scher Jugendgruppen). Einige der genannten Raubdrucke aus der Schriften reihe Archiv antiautoritiire Erziehung konnte ich beziehen über den Pack papier-Versand, 4500 Osnabrück, Postfach. 662 Abbott, Lyman (1908): A Republic in the Republic. In: Outlook (New Y ork) 88.1908,: 350-354. Adams, John (Ed. 1924): Educational Movements and Methods. London: Harrap 1924. Adlboch, Walter (1951): Father Flanagans Boys Town. In: Jugendwohl (Freiburg!Breisgau) 32.1951,11: 306-313.