The Study of Participant Reference in Some of the Narratives in Ferdowsi’S Shahnameh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

International Mevlana Symposiuın Papers

International Mevlana Symposiuın Papers ,. Birleşmiş Minetler 2007 Eğitim, Bilim ve Kültür MevlAnA CelAleddin ROmi Kurumu 800. ~um Yıl Oönümü United Nations Educaöonal, Scientific and aoo:ı Anniversary of Cu/tura! Organlzatlon the Birth of Rumi Symposium organization commitlee Prof. Dr. Mahmut Erol Kılıç (President) Celil Güngör Volume 3 Ekrem Işın Nuri Şimşekler Motto Project Publication Tugrul İnançer Istanbul, June 20 ı O ISBN 978-605-61104-0-5 Editors Mahmut Erol Kılıç Celil Güngör Mustafa Çiçekler Katkıda bulunanlar Bülent Katkak Muttalip Görgülü Berrin Öztürk Nazan Özer Ayla İlker Mustafa İsmet Saraç Asude Alkaylı Turgut Nadir Aksu Gülay Öztürk Kipmen YusufKat Furkan Katkak Berat Yıldız Yücel Daglı Book design Ersu Pekin Graphic application Kemal Kara Publishing Motto Project, 2007 Mtt İletişim ve Reklam Hizmetleri Şehit Muhtar Cad. Tan Apt. No: 13 1 13 Taksim 1 İstanbul Tel: (212) 250 12 02 Fax: (212) 250 12 64 www.mottoproject.com 8-12 Mayıs 2007 Bu kitap, tarihinde Kültür ve yayirı[email protected] Turizm Bakanlıgı himayesinde ve Başbakanlık Tamtma Fonu'nun katkılanyla İstanbul ve Konya'da Printing Mas Matbaacılık A.Ş. düzerılenen Uluslararası Mevhiııfı Sempozyumu bildirilerini içermektedir. Hamidiye Mahallesi, Soguksu Caddesi, No. 3 Kagıtlıane - İstanbul The autlıors are responsible for tlıe content of tlıe essays .. Tei. 0212 294 10 00 "W e are the inheritors of the lig ht of Muhammad": Rumi, ada b, and Muhammadan intimacy ümid Safi 1 lran 1 WlLL begin by two stories about relations between Mawlana and his do se companions, each revealing one facet of his un derstanding of the Prophet. One day Shaykh Shas al-Din Multi (Malati?) had come to see Mawlana. -

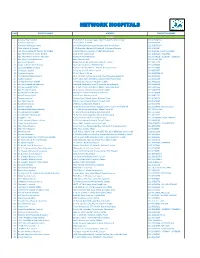

Network Hospitals

NETWORK HOSPITALS S.NO HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBERS KARACHI 1 Adamjee Eye Hospital 39-B, Block C, Adamjee Nagar, Opp. Zubaida Hospital, Dhoraji 021-34132824-6 2 Advanced Eye Clinic 17-C/1, Block 6, PECHS 021-34540999 3 Advanced Radiology Centre Behind Hamdard University Hospital, M.A. Jinnah Road 021-32783535-6 4 Afsar Memorial Hospital B-35 Khalid Bin Waleed Rd, Sector W, Gulshan-e-Maymar 021-36353124 5 Aga Khan Hospital for Women Karimabad Ayesha Manzil, at junction of Shahrah-e-Pakistan 021-3682296-3 / 021-33100006 6 Aga Khan Maternity Home Garden Gold Street, Garden East 021-33100005 / 32256903 7 Aga Khan Maternity Home Kharadar Atmaram Pritamdas Road 021-32524618 / 32542187 / 33100007 8 Aga Khan University Hospital Main Stadium Road 021 111-911-911 9 Akhter Eye Hospital Rashid Minhas Rd, 4/C Block 5 Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34811979 10 Al Ain Institute of Eye Disease Shahrah-e-Quaideen, PECHS Block 2 021-34556460 11 Al Hadeed Medical Centre Gulshan e Hadeed Phase 1 Phase 1 Bin Qasim Town 021-34713800 12 Al Rayyaz Hospital St-24, Sector 11/B, North Karachi 021-36907697 13 Altamash Hospital ST 9A / Block 1, Clifton 021-35187000-16 14 Arif Defence Medical Centre DK-1, Off 34th Commercial Street, Main Khayaban-e-Bukhari 021-35155631 15 Asghar Hospital KDA Market, KDA roundabout, Block B North Nazimabad 021-36642389 16 Ashfaq Memorial Hospital University Rd, Block 13 C Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34822261 17 Asif Eye Hospital Bahadarabad Westland Apartment, Ismail Chowrangi, Bahadurabad 021-34944530 18 Asif Eye Hospital Clifton 65-C, 24th Commercial Street, Phase II Extension, DHA 021-35385166 19 Atia General Hospital 48-A, Darakhshan Society, Kala Board, Malir 021-34400726 20 Ayesha General Hospital Gulshan-e- Hadeed C-50 Phase -3 Side Rd 021 34716608 21 Azam Town Hospital Azam Town, Mehmoodabad 021-35801741 22 Banaras Hospital Banaras Bazar Chowk, Sector 8 Orangi Town, 021-34150416 23 Bay View Hospital 205 A-ll, Saba Avenue, Zone A Phase 8, DHA 021-35246225 24 Boulevard Hospital 17th East Street, D.H.A. -

Hafeez Jalandhari - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Hafeez Jalandhari - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Hafeez Jalandhari(14 January 1900 - 21 December 1982) Abu-Al-Asar Hafeez Jalandhari (Urdu: ??? ????? ???? ????????) Pakistani writer, poet and, above all, composer of the National Anthem of Pakistan. He was born in Jalandhar, Punjab, British India on January 14, 1900. After independence of Pakistan in 1947, Hafeez Jalandhari moved to Lahore. Hafeez made up for the lack of formal education with self-study but he has the privilege to have some advise from the great Persian poet Maulana Ghulam Qadir Bilgrami. His dedication, hard work and advise from such a learned person carved his place in poetic pantheon. Hafeez Jalandhari actively participated in Pakistan Movement and used his writings to propagate for the cause of Pakistan. In early 1948, he joined the forces for the freedom of Kashmir and got wounded. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the Kashmiri Anthem, "Watan Hamara Azad Kashmir". He wrote many patriotic songs during Pakistan, India war in 1965. Hafeez Jalandhari served as Director General of morals in Pakistan Armed Forces, and very prominent position as adviser to the President, Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan and also Director of Writer's Guild. Hafeez Jalandhari's monumental work of poetry, Shahnam-e-Islam, gave him incredible fame which, in the manner of Firdowsi's Shahnameh, is a record of the glorious history of Islam in verse. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the national anthem of Pakistan composed by Ahmed Ghulamali Chagla also known as Ahmed G Chagla. He is unique in Urdu poetry for the enchanting melody of his voice and lilting rhythms of his songs and lyrics. -

Jami and Nava'i/Fani's Rewritings of Hafez's Opening Ghazal

Imitational Poetry as Pious Hermeneutics? Jami and Nava’i/Fani’s Rewritings of Hafez’s Opening Ghazal Marc Toutant To cite this version: Marc Toutant. Imitational Poetry as Pious Hermeneutics? Jami and Nava’i/Fani’s Rewritings of Hafez’s Opening Ghazal. Charles Melville. The Timurid Century, 9, I.B. Tauris, 2020, The Idea of Iran, 9781838606886. hal-02906016 HAL Id: hal-02906016 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02906016 Submitted on 23 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Imitational Poetry as Pious Hermeneutics? Jami and Nava’i/Fani’s Rewritings of Hafez’s Opening Ghazal Marc Toutant (CNRS Paris) He was the unique of the age (nadera-ye zaman) and a prodigy of the world (o‘juba-ye jahan). These are the first words with which Dowlatshah Samarqandi begins the notice he devotes to Hafez in his Tazkerat al-sho‘ara in 1486. Then he adds: ‘His excellence (fazilat) and his perfection (kamal) are endless and the art of poetry is unworthy of his rank. He is incomparable in the science of Qur’an and he is illustrious in the sciences of the exoteric (zaher) and the esoteric (baten).’1 Although Hafez died in 1389, his poetry was widely celebrated one century later, as shown by Dowlatshah’s eulogy. -

Persian 2704 SP15.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Persian 2704 Introduction to Persian Epic Instructor: Office Hours: Office: Email: No laptops, phones, or other mobile devices may be used in class. This course is about the Persian Book of Kings, Shahnameh, of the Persian poet Abulqasim Firdawsi. The Persian Book of Kings combines mythical themes and historical narratives of Iran into a mytho-historical narrative, which has served as a source of national and imperial consciousness over centuries. At the same time, it is considered one of the finest specimen of Classical Persian literature and one of the world's great epic tragedies. It has had an immense presence in the historical memory and political culture of various societies from Medieval to Modern, in Iran, India, Central Asia, and the Ottoman Empire. Yet a third aspect of this monumental piece of world literature is its presence in popular story telling tradition and mixing with folk tales. As such, a millennium after its composition, it remains fresh and rife in cultural circles. We will pursue all of those lines in this course, as a comprehensive introduction to the text and tradition. Specifically, we will discuss the following in detail: • The creation of Shahname in its historical context • The myth and the imperial image in the Shahname • Shahname as a cornerstone of “Iranian” identity. COURSE MATERIAL: • Shahname is available in English translation. -

NEWSLETTER CENTER for IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol

CIS NEWSLETTER CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 13, No.2 MEALAC–Columbia University–New York Fall 2001 Encyclopædia Iranica: Volume X Published Fascicle 1, Volume XI in Press With the publication of fascicle ISLAMIC PERSIA: HISTORY AND 6 in the Summer of 2001, Volume BIOGRAPHY X of the Encyclopædia Iranica was Eight entries treat Persian his- completed. The first fascicle of Vol- tory from medieval to modern ume XI is in press and will be pub- times, including “Golden Horde,” lished in December 2001. The first name given to the Mongol Khanate fascicle of volume XI features over 60 ruled by the descendents of Juji, the articles on various aspects of Persian eldest son of Genghis Khan, by P. Jack- culture and history. son. “Golshan-e Morad,” a history of the PRE-ISLAMIC PERSIA Zand Dynasty, authored by Mirza Mohammad Abu’l-Hasan Ghaffari, by J. Shirin Neshat Nine entries feature Persia’s Pre-Is- Perry. “Golestan Treaty,” agreement lamic history and religions: “Gnosti- arranged under British auspices to end at Iranian-American Forum cism” in pre-Islamic Iranian world, by the Russo-Persian War of 1804-13, by K. Rudolph. “Gobryas,” the most widely On the 22nd of September, the E. Daniel. “Joseph Arthur de known form of the old Persian name Encyclopædia Iranica’s Iranian-Ameri- Gobineau,” French man of letters, art- Gaub(a)ruva, by R. Schmitt. “Giyan ist, polemist, Orientalist, and diplomat can Forum (IAF) organized it’s inau- Tepe,” large archeological mound lo- who served as Ambassador of France in gural event: a cocktail party and pre- cated in Lorestan province, by E. -

Susa and Memnon Through the Ages 15 4

Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture www.dabirjournal.org Digital Archive of Brief notes & Iran Review ISSN: 2470-4040 Vol.01 No.04.2017 1 xšnaoθrahe ahurahe mazdå Detail from above the entrance of Tehran’s fire temple, 1286š/1917–18. Photo by © Shervin Farridnejad The Digital Archive of Brief Notes & Iran Review (DABIR) ISSN: 2470-4040 www.dabirjournal.org Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture University of California, Irvine 1st Floor Humanities Gateway Irvine, CA 92697-3370 Editor-in-Chief Touraj Daryaee (University of California, Irvine) Editors Parsa Daneshmand (Oxford University) Arash Zeini (Freie Universität Berlin) Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Judith A. Lerner (ISAW NYU) Book Review Editor Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Advisory Board Samra Azarnouche (École pratique des hautes études); Dominic P. Brookshaw (Oxford University); Matthew Canepa (University of Minnesota); Ashk Dahlén (Uppsala University); Peyvand Firouzeh (Cambridge University); Leonardo Gregoratti (Durham University); Frantz Grenet (Collège de France); Wouter F.M. Henkelman (École Pratique des Hautes Études); Rasoul Jafarian (Tehran University); Nasir al-Ka‘abi (University of Kufa); Andromache Karanika (UC Irvine); Agnes Korn (Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main); Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (University of Edinburgh); Jason Mokhtarain (University of Indiana); Ali Mousavi (UC Irvine); Mahmoud Omidsalar (CSU Los Angeles); Antonio Panaino (Univer- sity of Bologna); Alka Patel (UC Irvine); Richard Payne (University of Chicago); Khodadad Rezakhani (Princeton University); Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis (British Museum); M. Rahim Shayegan (UCLA); Rolf Strootman (Utrecht University); Giusto Traina (University of Paris-Sorbonne); Mohsen Zakeri (Univer- sity of Göttingen) Logo design by Charles Li Layout and typesetting by Kourosh Beighpour Contents Articles & Notes 1. -

The Scarlet Stone: Retelling the Tale of National Identity (English)

Bijan Khalili Iranshahr Magazine, Los Angeles, CA. August 21, 2015. Translated by Hooman Rahimi (EN 15038 and ISO 17100 certified translator) Los Angeles Awaiting The Scarlet Stone’s Premier “The Scarlet Stone”, Retelling the Tale of National Identity The Scarlet Stone is the title of a drama that will be brought to stage on August 29th, 2015 at UCLA’s Royce Hall. It is a show that has caught the attention of the Iranian community of art enthusiasts located in Southern California from long ago. Shahrokh Yadegari has adapted the script for The Scarlet Stone based on a poem with the same title by Siavash Kasrai. However, this work of art has gone beyond the distinguished poem of Siavash Kasrai by telling a story as long as the history of Iran itself through an amazing return to the Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, and in the process, adding in a new form to the Iranian art history in diaspora. The Scarlet Stone is an allegory of the emblem given to Tahmineh by Rostam, the Iranian mythological hero, so that if their child was born a girl, she would tie the emblem to their daughter’s hair and to his arm if the child was a boy. In this way, the warrior father could identify his child. Rostam and Sohrab is one of the most importnat stories of the Shahnameh. Alas! Rostam recognizes the scarlet stone tied to the arm of his thriving son too late --- the moment when no elixir is effective against the father’s imposed deep wound on the son’s lifeless body. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

A Vivid Research on Gundīshāpūr Academy, the Birthplace of the Scholars and Physicians Endowed with Scientific and Laudable Q

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Soial Science (SSRG-IJHSS) – Volume 7 Issue 5 – Sep - Oct 2020 A Vivid Research on Gundīshāpūr Academy, the Birthplace of the Scholars and Physicians Endowed with Scientific and laudable qualities Mahmoud Abbasi1, Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan)2 Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Medical Ethics and Law Research Center, Tehran, Iran. Abstract: Iran also known as Persia, like its neighbor Iraq, can be studied as ancient civilization or a modern nation. Ac- cording to Iranian mythology King Jamshīd introduced to his people the science of medicine and the arts and crafts. Before the establishment of Gundīshāpūr Academy, medical and semi-medical practices were exclusively the profession of a spe- cial group of physicians who belonged to the highest rank of the social classes. The Zoroastrian clergymen studied both theology and medicine and were called Atrāvān. Three types physicians were graduated from the existing medical schools of Hamedan, Ray and Perspolis. Under the Sasanid dynasty Gundīshāpūr Academy was founded in Gundīshāpūr city which became the most important medical center during the 6th and 7th century. Under Muslim rule, at Bayt al-Ḥikma the systematic methods of Gundīshāpūr Academy and its ethical rules and regulations were emulated and it was stuffed with the graduates of the Academy. Finally, al-Muqaddasī (c.391/1000) described it as failing into ruins. Under the Pahlavī dynasty and Islamic Republic of Iran, the heritage of Gundīshāpūr Academy has been memorized by founding Ahwaz Jundīshāpūr University of Medical Sciences. Keywords: Gundīshāpūr Academy, medical school, teaching hospital, Bayt al-Ḥikma, Ahwaz Jundīshāpūr University of Medical Science, and Medical ethics.