APSA Presidential Address: the Public Role of Political Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016 Professor: Office: Office Phone: Office Hours: Email: Course Description and Learning Outcomes Comparative politics is perhaps the broadest field of political science. This course will introduce students to the major theoretical approaches employed in comparative politics. The major debates and controversies in the field will be examined. Although some associate comparative politics with “the comparative method,” those conducting research in the area of comparative politics use a multitude of methodologies and pursue diverse topics. In this course, students will analyze and discuss the theoretical approaches and methods used in comparative politics. Course Requirements Class participation and attendance. Students must come to class prepared, having completed all of the required reading, and ready to actively discuss the material at hand. Each student must submit comments/questions on the assigned readings for six classes (not including the class you help facilitate). Please e-mail them to me by noon on the day of class. Students are expected to attend each class. Missing classes will have a deleterious effect on this portion of the grade. Arriving late, leaving early, or interrupting class with a phone or other electronic device will also result in a drop in the student’s grade. Students are not allowed to sleep, read newspapers or anything else, listen to headphones, TEXT, or talk to others during class. You must turn off all electronic devices during class. Any exceptions must be cleared with me in advance. Laptop computers and iPads are allowed for taking notes ONLY. I reserve the right to ban laptops, iPads, and so forth. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

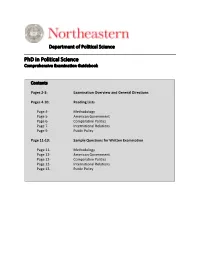

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

US Racial Politics II New Deal to the Present

U.S. Racial Politics: New Deal to the Present Political Science 449/549 CRN: 37625 Professor: Joseph Lowndes Office: PLC 919 email: [email protected] Graduate Employee: Course description: In this course, we will examine the ways that race shaped the major political dynamics in the United States from the Great Depression to the present. Materials: There are two books for this course, available in the bookstore. The books are The Unsteady March, by Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith; and When Affirmative Action Was White, by Ira Katznelson. PS 5549 will have one additional text: Lowndes, Novkov and Warren, eds. Race and American Political Development. All other readings will be available on Canvas. Requirements for 449: This is a heavy reading course 1. Seven in-class quizzes. These quizzes will assess your comprehension of the assigned reading, lectures and class discussions. Your lowest two scores will be dropped. No make-up quizzes are possible. (50% of final grade) 2. Midterm in-class exam (25% of final grade) 3. Final exam (25% of final grade) 4. Participation: Students will be expected to attend class and participate in class discussions. Constructive, informed, respectful participation that contributes directly to conversations about the course material will raise borderline grades; lack of participation may result in lower grades. Requirements for 549: Research paper 18-20 pages, due Wednesday of Finals Week. Meet with me by 4th week with thesis topic to discuss. Policies: Students with disabilities. If you have a documented disability and anticipate needing accommodations in this course, please make arrangements to meet with the professor soon. -

Introduction to American Political Culture

Bellevue College INTRODUCTION TO AMERICAN POLITICAL CULTURE Political Science 160/Cultural & Ethnic Studies 160 Item 5361 A (POLS 160) or 5638 (CES 160) (Five Credits)1 Winter 2011 (Jan. 3-March 22), 11:30 a.m.-12:20 p.m. (L-221) Dr. T. M. Tate (425) 564-2169 [email protected] Office: D-200C Office Hours: See MyBC course site Pre-requisite: None Course Description This course treats the ways in which American cultural patterns influence and shape political outcomes and public policy. Study of the political culture may shed light on the nature of the political struggles and on the policy process in general. Political outcomes in the United States are not random but are structured and connected by certain enduring values. We seek answers to questions such as: How do Americans thinks about government, political institutions, social welfare, and the market? What are the origins and sources of American political culture? How has it changed over time, and what factors account for this change? How is American political culture distinctive, and how is it being reshaped in a time of globalization? In the process of this broad inquiry, we necessarily treat concepts such as democracy, liberty, individualism, American “exceptionalism,” political community, and political culture itself. Learning Outcomes On completion of this course, you should be able to: Explain the concept of political culture and its relevance to contemporary political society. 1 One credit hour of this course is online via MyBC. Identify the core values in American political culture and understand their influences on political life. Demonstrate how the political culture influences and shapes American politics and the policy process. -

Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium)

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 7 Issue 2 Article 2 Spring 2000 Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium) Linda Bosniak Rutgers Law School-Camden Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Bosniak, Linda (2000) "Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium)," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol7/iss2/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Citizenship Denationalized LINDA BOSNIAK° INTRODUCTION When Martha Nussbaum declared herself a "citizen of the world" in a recent essay, the response by two dozen prominent intellectuals was overwhelmingly critical.' Nussbaum's respondents had a variety of complaints, but central among them was the charge that the very notion of world citizenship is incoherent. For citizenship requires a formal governing polity, her critics asserted, and clearly no such institution exists at the world level. Short of the establishment of interplanetary relations, a world government is unlikely to take form anytime soon. A good thing too, they added, since such a regime would surely be a tyrannical nightmare.2 * Professor of Law, Rutgers Law School-Camden; B.A., Wesleyan University; M.A., University of California, Berkeley; J.D., Stanford University. -

Weatherhead Center for International Affairs

WEATHERHEAD CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS H A R V A R D U N I V E R S I T Y two2004-2005 thousand four – two thousand five ANNUAL REPORTS two2005-2006 thousand five – two thousand six 1737 Cambridge Street • Cambridge, MA 02138 www.wcfia.harvard.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 PEOPLE Visiting Committee 4 Executive Committee 4 Administration 6 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES Small Grants for Faculty Research Projects 8 Medium Grants for Faculty Research Projects 9 Large Grants for Faculty Research Projects 9 Large Grants for Faculty Research Semester Leaves 9 Distinguished Lecture Series 11 Weatherhead Initiative in International Affairs 12 CONFERENCES 13 RESEARCH SEMINARS Challenges of the Twenty-First Century 34 Communist and Postcommunist Countries 35 Comparative Politics Research Workshop 36 Comparative Politics Seminar 39 Director’s Faculty Seminar 39 Economic Growth and Development 40 Harvard-MIT Joint Seminar on Political Development 41 Herbert C. Kelman Seminar on International Conflict Analysis and Resolution 42 International Business 43 International Economics 45 International History 48 Middle East 49 Political Violence and Civil War 51 Science and Society 51 South Asia 52 Transatlantic Relations 53 U.S. Foreign Policy 54 RESEARCH PROGRAMS Canada Program 56 Fellows Program 58 Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies 65 John M. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies 74 Justice, Welfare, and Economics 80 Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival 82 Religion, Political Economy, and Society 84 Student Programs 85 Transnational Studies Initiative 95 U.S.-Japan Relations 96 PUBLICATIONS 104 ANNUAL REPORTS 2004–2005 / 2005–2006 - 1 - INTRODUCTION In August 2005, the Weatherhead Center moved In another first, the faculty research semester to the new Center for Government and leaves that the Center awarded in spring 2005 International Studies (CGIS) complex. -

Toward a More Democratic Congress?

TOWARD A MORE DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS? OUR IMPERFECT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION: THE CRITICS EXAMINED STEPHEN MACEDO* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 609 I. SENATE MALAPPORTIONMENT AND POLITICAL EQUALITY................. 611 II. IN DEFENSE OF THE SENATE................................................................ 618 III. CONSENT AS A DEMOCRATIC VIRTUE ................................................. 620 IV. REDISTRICTING AND THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE REFORM? ................ 620 V. THE PROBLEM OF GRIDLOCK, MINORITY VETOES, AND STATUS- QUO BIAS: UNCLOGGING THE CHANNELS OF POLITICAL CHANGE?.... 622 CONCLUSION................................................................................................... 627 INTRODUCTION There is much to admire in the work of those recent scholars of constitutional reform – including Sanford Levinson, Larry Sabato, and prior to them, Robert Dahl – who propose to reinvigorate our democracy by “correcting” and “revitalizing” our Constitution. They are right to warn that “Constitution worship” should not supplant critical thinking and sober assessment. There is no doubt that our 220-year-old founding charter – itself the product of compromise and consensus, and not only scholarly musing – could be improved upon. Dahl points out that in 1787, “[h]istory had produced no truly relevant models of representative government on the scale the United States had already attained, not to mention the scale it would reach in years to come.”1 Political science has since progressed; as Dahl also observes, none of us “would hire an electrician equipped only with Franklin’s knowledge to do our wiring.”2 But our political plumbing is just as archaic. I, too, have participated in efforts to assess the state of our democracy, and co-authored a work that offers recommendations, some of which overlap with * Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values; Director of the University Center for Human Values, Princeton University. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H.