5 Skates and Rays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notoraja Martinezi Sp. Nov., a New Species of Deepwater Skate and The

Zootaxa 4098 (1): 179–190 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4098.1.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C7826AC7-6493-42D3-A0A4-89FEBB5AB3E3 Notoraja martinezi sp. nov., a new species of deepwater skate and the first record of the genus Notoraja Ishiyama, 1958 (Rajiformes: Arhynchobatidae) from the eastern Pacific Ocean FRANCISCO J. CONCHA1,2,7, DAVID A. EBERT3,4,5 & DOUGLAS J. LONG4,6 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut. 75 North Eagleville Road – Unit 3043 Storrs, CT, 06269, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Facultad de Ciencias del Mar y de Recursos Naturales, Universidad de Valparaíso. Av. Borgoño 16344, Viña del Mar, Chile. 3Pacific Shark Research Center, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, CA 95039, USA. 4Department of Ichthyology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA. 94118, USA. 5South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, Private Bag 1015, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] state.edu. 6Department of Biology, St. Mary’s College, 1928 St. Mary’s Road, Moraga, California 94575. E-mail: [email protected] 7Corresponding author Abstract A new arhynchobatid skate, Notoraja martinezi, sp. nov., is described from four specimens collected from the eastern Central Pacific from Costa Rica to Ecuador and between depths of 1256–1472 m. The new species is placed in the genus Notoraja based on the long and flexible rostrum and its proportionally long tail with respect to total length. -

Bibliography Database of Living/Fossil Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii, Holocephali) Papers of the Year 2016

www.shark-references.com Version 13.01.2017 Bibliography database of living/fossil sharks, rays and chimaeras (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii, Holocephali) Papers of the year 2016 published by Jürgen Pollerspöck, Benediktinerring 34, 94569 Stephansposching, Germany and Nicolas Straube, Munich, Germany ISSN: 2195-6499 copyright by the authors 1 please inform us about missing papers: [email protected] www.shark-references.com Version 13.01.2017 Abstract: This paper contains a collection of 803 citations (no conference abstracts) on topics related to extant and extinct Chondrichthyes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) as well as a list of Chondrichthyan species and hosted parasites newly described in 2016. The list is the result of regular queries in numerous journals, books and online publications. It provides a complete list of publication citations as well as a database report containing rearranged subsets of the list sorted by the keyword statistics, extant and extinct genera and species descriptions from the years 2000 to 2016, list of descriptions of extinct and extant species from 2016, parasitology, reproduction, distribution, diet, conservation, and taxonomy. The paper is intended to be consulted for information. In addition, we provide information on the geographic and depth distribution of newly described species, i.e. the type specimens from the year 1990- 2016 in a hot spot analysis. Please note that the content of this paper has been compiled to the best of our abilities based on current knowledge and practice, however, -

Breaking with Tradition: Redefining Measures for Diet Description with a Case Study of the Aleutian Skate Bathyraja Aleutica (Gilbert 1896)

Environ Biol Fish (2012) 95:3–20 DOI 10.1007/s10641-011-9959-z Breaking with tradition: redefining measures for diet description with a case study of the Aleutian skate Bathyraja aleutica (Gilbert 1896) Simon C. Brown & Joseph J. Bizzarro & Gregor M. Cailliet & David A. Ebert Received: 1 September 2010 /Accepted: 27 October 2011 /Published online: 16 November 2011 # Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Characterization of fish diets from stomach Aleutian skate Bathyraja aleutica from specimens content analysis commonly involves the calculation of collected from three ecoregions of the northern Gulf multiple relative measures of prey quantity (%N,%W,% of Alaska (GOA) continental shelf during June- FO), and their combination in the standardized Index of September 2005–2007. Aleutian skate were found to Relative Importance (%IRI). Examining the underlying primarily consume the commonly abundant benthic structure of dietary data matrices reveals interdependen- crustaceans, northern pink shrimp Pandalus eous and cies among diet measures, and obviates the advantageous Tanner crab Chionoecetes bairdi, and secondarily use of underused prey-specific measures to diet charac- consume various teleost fishes. Multivariate variance terization. With these interdependencies clearly realized partitioning by Redundancy Analysis revealed spa- as formal mathematical expressions, we proceed to tially driven differences in the diet to be as influential isolate algebraically, the inherent bias in %IRI, and as skate size, sex, and depth of capture. Euphausiids provide a correction for it by substituting traditional and other mid-water prey in the diet were strongly measures with prey-specific measures. The resultant new associated with the Shelikof Strait region during 2007 index, the Prey-Specific Index of Relative Importance (% that may be explained by atypical marine climate PSIRI), is introduced and recommended to replace %IRI conditions during that year. -

Age, Growth, and Sexual Maturity of the Deepsea Skate, Bathyraja

AGE, GROWTH, AND SEXUAL MATURITY OF THE DEEPSEA SKATE, BATHYRAJA ABYSSICOLA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Alaska Pacific University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science by Cameron Murray Provost April 2016 Pro Q u est Nu m b er: 10104548 All rig hts reserv e d INF O RM ATI O N T O ALL USERS Th e q u a lity of this re pro d u ctio n is d e p e n d e nt u p o n th e q u a lity of th e c o p y su b mitt e d. In th e unlik e ly e v e nt th a t th e a uth or did n ot se n d a c o m ple t e m a nuscript a n d th ere are missin g p a g es, th ese will b e n ot e d. Also, if m a t eria l h a d to b e re m o v e d, a n ot e will in dic a t e th e d e le tio n. Pro Q u est 10104548 Pu blish e d b y Pro Q u est LL C (2016). C o p yrig ht of th e Dissert a tio n is h e ld b y th e A uth or. All rig hts reserv e d. This w ork is prot e ct e d a g a inst un a uth orize d c o p yin g un d er Title 17, Unit e d St a t es C o d e Microform Editio n © Pro Q u est LL C . -

Beringraja Binoculata) and Longnose Skate (Raja Rhina)

Bomb Dating and Age Estimates of Big Skate (Beringraja binoculata) and Longnose Skate (Raja rhina) Jacquelynne King, Fisheries and Oceans Canada David Ebert, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories Craig Kastelle, Alaska Fisheries Science Center Thomas Helser, Alaska Fisheries Science Center Christopher Gburski, Alaska Fisheries Science Center Gregor Cailliet, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories ABSTRACT MATERIALS AND METHODS RESULTS Age and growth curve estimates have been produced for big skate Bomb radiocarbon analyses Big skate (Beringraja binoculata [formerly Raja binoculata]) and longnose skate 1. Big skate (n=12) and longnose skate (n=33) vertebrae were collected • the estimated birth years ranged from 1965-1970 (Raja rhina) populations in the Gulf of Alaska, British Columbia and during the early 1980s off California. These fishes were estimated to • there were no low ∆14C values for big skate California. Age estimation for these two skate species relies on growth be alive during the atmospheric testing of atomic bombs which resulted Longnose skate band counts of sectioned vertebrae. However these studies have not in the rapid increase in oceanic radiocarbon (14C). • the ∆14C values for longnose skate overlapped with mid to top portion of the produced similar results for either species, highlighting the need for age 2. Vertebrae where thin (0.7-1.0 mm) sectioned and mounted on ∆14C reference curve for Petrale sole (Fig. 3) validation. Archived large specimens of big skate and longnose skate microscope slides. • these skate were not as old as originally estimated but there were early collected in 1980 and 1981 had minimum age estimates old enough to 3. Ages were estimated based on vertebral band counts (Fig. -

By Species Items

1 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc Capture production by species items Mediterranean and Black Sea C-37 Poissons, crustacés, mollusques, etc Captures par catégories d'espèces Méditerranée et mer Noire (a) Peces, crustáceos, moluscos, etc Capturas por categorías de especies Mediterráneo y Mar Negro English name Scientific name Species group Nom anglais Nom scientifique Groupe d'espèces 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Nombre inglés Nombre científico Grupo de especies t t t t t t t Freshwater bream Abramis brama 11 495 335 336 108 47 7 10 Common carp Cyprinus carpio 11 3 1 - 2 3 4 4 Roach Rutilus rutilus 11 1 1 2 7 11 12 5 Roaches nei Rutilus spp 11 13 78 73 114 72 83 47 Sichel Pelecus cultratus 11 105 228 276 185 147 52 39 Cyprinids nei Cyprinidae 11 - - 167 159 95 141 226 European perch Perca fluviatilis 13 - - - 1 1 - - Percarina Percarina demidoffi 13 - - - - 18 15 202 Pike-perch Stizostedion lucioperca 13 3 031 2 568 2 956 3 504 3 293 2 097 1 043 Freshwater fishes nei Osteichthyes 13 - - - 17 - 249 - Danube sturgeon(=Osetr) Acipenser gueldenstaedtii 21 114 36 20 8 10 3 3 Sterlet sturgeon Acipenser ruthenus 21 - - 0 - - - - Starry sturgeon Acipenser stellatus 21 13 11 5 3 5 1 1 Beluga Huso huso 21 12 10 1 0 4 1 3 Sturgeons nei Acipenseridae 21 290 185 59 22 23 14 8 European eel Anguilla anguilla 22 917 682 464 602 642 648 522 Salmonoids nei Salmonoidei 23 26 - - 0 - - 7 Pontic shad Alosa pontica 24 153 48 15 21 112 68 115 Shads nei Alosa spp 24 2 742 2 640 2 095 2 929 3 984 2 831 3 645 Azov sea sprat Clupeonella cultriventris 24 3 496 10 862 12 006 27 777 27 239 17 743 14 538 Three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus 25 - - - 8 4 6 1 European plaice Pleuronectes platessa 31 - 0 6 7 7 5 5 European flounder Platichthys flesus 31 69 62 56 29 29 11 43 Common sole Solea solea 31 5 047 4 179 5 169 4 972 5 548 6 273 5 619 Wedge sole Dicologlossa cuneata 31 .. -

Status of the Fisheries Report an Update Through 2008

STATUS OF THE FISHERIES REPORT AN UPDATE THROUGH 2008 Photo credit: Edgar Roberts. Report to the California Fish and Game Commission as directed by the Marine Life Management Act of 1998 Prepared by California Department of Fish and Game Marine Region August 2010 Acknowledgements Many of the fishery reviews in this report are updates of the reviews contained in California’s Living Marine Resources: A Status Report published in 2001. California’s Living Marine Resources provides a complete review of California’s three major marine ecosystems (nearshore, offshore, and bays and estuaries) and all the important plants and marine animals that dwell there. This report, along with the Updates for 2003 and 2006, is available on the Department’s website. All the reviews in this report were contributed by California Department of Fish and Game biologists unless another affiliation is indicated. Author’s names and email addresses are provided with each review. The Editor would like to thank the contributors for their efforts. All the contributors endeavored to make their reviews as accurate and up-to-date as possible. Additionally, thanks go to the photographers whose photos are included in this report. Editor Traci Larinto Senior Marine Biologist Specialist California Department of Fish and Game [email protected] Status of the Fisheries Report 2008 ii Table of Contents 1 Coonstripe Shrimp, Pandalus danae .................................................................1-1 2 Kellet’s Whelk, Kelletia kelletii ...........................................................................2-1 -

Stomach Content Analysis of Short-Finned Pilot Whales

f MARCH 1986 STOMACH CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SHORT-FINNED PILOT WHALES h (Globicephala macrorhynchus) AND NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS (Mirounga angustirostris) FROM THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA BIGHT by Elizabeth S. Hacker ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT LJ-86-08C f This Administrative Report is issued as an informal document to ensure prompt dissemination of preliminary results, interim reports and special studies. We recommend that it not be abstracted or cited. STOMACH CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SHORT-FINNED PILOT WHALES (GLOBICEPHALA MACRORHYNCHUS) AND NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS (MIROUNGA ANGUSTIROSTRIS) FROM THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA BIGHT Elizabeth S. Hacker College of Oceanography Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331 March 1986 S H i I , LIBRARY >66 MAR 0 2 2007 ‘ National uooarac & Atmospheric Administration U.S. Dept, of Commerce This report was prepared by Elizabeth S. Hacker under contract No. 84-ABA-02592 for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Center, La Jolla, California. The statements, findings, conclusions and recommendations herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Marine Fisheries Service. Charles W. Oliver of the Southwest Fisheries Center served as Contract Officer's Technical Representative for this contract. ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT LJ-86-08C CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION.................. 1 METHODS....................... 2 Sample Collection........ 2 Sample Identification.... 2 Sample Analysis.......... 3 RESULTS....................... 3 Globicephala macrorhynchus 3 Mirounga angustirostris... 4 DISCUSSION.................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............. 11 REFERENCES.............. 12 i LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE 1 Collection data for Globicephala macrorhynchus examined from the Southern California Bight........ 19 2 Collection data for Mirounga angustirostris examined from the Southern California Bight........ 20 3 Stomach contents of Globicephala macrorhynchus examined from the Southern California Bight....... -

Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation of Skate Species (Rajidae)

16. Gulf of Alaska Skates by Sarah Gaichas1, Nick Sagalkin2, Chris Gburski1, Duane Stevenson1, and Rob Swanson3 1NMFS Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle WA 2ADF&G Commercial Fisheries Division, Kodiak AK 3NMFS Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Kodiak AK Executive Summary Summary of Major Changes Changes in the input data: 1. Total catch weight for GOA skates is updated with 2004 and partial 2005 data. 2. Biomass estimates from the 2005 GOA bottom trawl survey are incorporated. 3. Life history information has been updated with recent research results. 4. Information on the position of skates within the GOA ecosystem and the potential ecosystem effects of skate removals are included. Changes in assessment methodology: There are no changes to the Tier 5 assessment methodology. Changes in assessment results: No directed fishing for skates in the GOA is recommended, due to high incidental catch in groundfish and halibut fisheries. Skate biomass changed between the last NMFS GOA trawl survey in 2003 and the most recent survey in 2005, which changes the Tier 5 assessment results based on survey biomass. The recommendations for 2005 based on the three most recent survey biomass estimates for skates and M=0.10 are: Western Central GOA Eastern GOA GOA (610) (620, 630) (640, 650) Bathyraja skates Gulfwide Big skate ABC 695 2,250 599 ABC 1,617 OFL 927 3,001 798 OFL 2,156 Longnose skate ABC 65 1,969 861 OFL 87 2,625 1,148 Responses to SSC Comments SSC comments specific to the GOA Skates assessment: From the December, 2004 SSC minutes: The SSC is grateful to samplers with ADF&G who collected catch data and biological samples for Kodiak landings. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

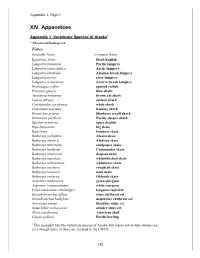

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS.