The Role of in Vitro Maturation in Fertility Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Vitro Fertilization for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

CLINICAL OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY Volume 64, Number 1, 39–47 Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. In Vitro Fertilization for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome JESSICA R. ZOLTON, DO,* and SAIOA TORREALDAY, MD† *Program in Reproductive Endocrinology and Gynecology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health; and †Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland Abstract: In vitro fertilization is indicated for infertile treatment for infertility. Guidelines indi- women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) after cate that IVF should be offered after failed unsuccessful treatment with ovulation induction agents or in women deemed high-risk of multiple gestations ovulation induction with oral agents or 1 who are ideal candidates for single embryo transfers. gonadotropin treatment. However, due to PCOS patients are at increased risk of ovarian hyper- the risk of twins and higher order multi- stimulation syndrome; therefore, attention should be ples, which is more commonly seen when made in the choice of in vitro fertilization treatment gonadotropin medications are utilized, protocol, dose of gonadotropin utilized, and regimen to achieve final oocyte maturation. Adopting these strat- IVF may be considered after failed ovula- egies in addition to close monitoring may significantly tion induction with clomiphene citrate or reduce the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome risk. letrozole.2 In addition, PCOS patients are Future developments may improve pregnancy out- ideal candidates for consideration of elec- comes and decrease complications in PCOS women tive single embryo transfer to mitigate the undergoing fertility treatment. Key words: infertility, in vitro fertilization, polycystic risk of multiple pregnancies while under- ovarian syndrome, ovarian hyperstimulation syn- going IVF. -

Oocyte Cryopreservation for Fertility Preservation in Postpubertal Female Children at Risk for Premature Ovarian Failure Due To

Original Study Oocyte Cryopreservation for Fertility Preservation in Postpubertal Female Children at Risk for Premature Ovarian Failure Due to Accelerated Follicle Loss in Turner Syndrome or Cancer Treatments K. Oktay MD 1,2,*, G. Bedoschi MD 1,2 1 Innovation Institute for Fertility Preservation and IVF, New York, NY 2 Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation, Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY abstract Objective: To preliminarily study the feasibility of oocyte cryopreservation in postpubertal girls aged between 13 and 15 years who were at risk for premature ovarian failure due to the accelerated follicle loss associated with Turner syndrome or cancer treatments. Design: Retrospective cohort and review of literature. Setting: Academic fertility preservation unit. Participants: Three girls diagnosed with Turner syndrome, 1 girl diagnosed with germ-cell tumor. and 1 girl diagnosed with lymphoblastic leukemia. Interventions: Assessment of ovarian reserve, ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval, in vitro maturation, and mature oocyte cryopreservation. Main Outcome Measure: Response to ovarian stimulation, number of mature oocytes cryopreserved and complications, if any. Results: Mean anti-mullerian€ hormone, baseline follical stimulating hormone, estradiol, and antral follicle counts were 1.30 Æ 0.39, 6.08 Æ 2.63, 41.39 Æ 24.68, 8.0 Æ 3.2; respectively. In Turner girls the ovarian reserve assessment indicated already diminished ovarian reserve. Ovarian stimulation and oocyte cryopreservation was successfully performed in all female children referred for fertility preser- vation. A range of 4-11 mature oocytes (mean 8.1 Æ 3.4) was cryopreserved without any complications. All girls tolerated the procedure well. -

First Unaffected Pregnancy Using Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis for Sickle Cell Anemia

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION First Unaffected Pregnancy Using Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis for Sickle Cell Anemia Kangpu Xu, PhD Context Sickle cell anemia is a common autosomal recessive disorder. However, pre- Zhong Ming Shi, MD implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) for this severe genetic disorder previously has not been successful. Lucinda L. Veeck, MLT, DSc Objective To achieve pregnancy with an unaffected embryo using in vitro fertiliza- Mark R. Hughes, MD, PhD tion (IVF) and PGD. Zev Rosenwaks, MD Design Laboratory analysis of DNA from single cells obtained by biopsy from em- ICKLE CELL ANEMIA IS ONE OF THE bryos in 2 IVF attempts, 1 in 1996 and 1 in 1997, to determine the genetic status of each embryo before intrauterine transfer. most common human autoso- mal recessive disorders. It is Setting University hospital in a large metropolitan area. caused by a mutation substitut- Patients A couple, both carriers of the recessive mutation for sickle cell disease. Sing thymine for adenine in the sixth Interventions Standard IVF treatment, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, embryo bi- codon (GAG to GTG) of the gene for the opsy, single-cell polymerase chain reaction and DNA analyses, embryo transfer to uterus, b-globin chain on chromosome 11p, pregnancy confirmation, and prenatal diagnosis by amniocentesis at 16.5 weeks’ ges- thereby encoding valine instead of glu- tation. tamic acid in the sixth position of the Main Outcome Measure DNA analysis of single blastomeres indicating whether globin chain. The frequency of sickle cell embryos carried the sickle cell mutation, allowing only unaffected or carrier embryos trait (carrier status) among the African to be transferred. -

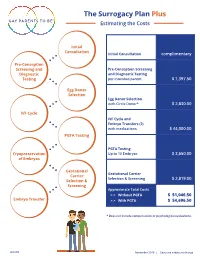

The Surrogacy Plan Plus Estimating the Costs

The Surrogacy Plan Plus Estimating the Costs Initial Consultation Initial Consultation complimentary Pre-Conception Screening and Pre-Conception Screening Diagnostic and Diagnostic Testing Testing per intended parent $ 1,397.50 Egg Donor Selection Egg Donor Selection with Circle Donor* $ 2,830.00 IVF Cycle IVF Cycle and Embryo Transfers (2) with medications $ 44,000.00 PGTA Testing PGTA Testing Cryopreservation Up to 10 Embryos $ 3,650.00 of Embryos Gestational Gestational Carrier Carrier Selection & Screening $ 2,819.00 Selection & Screening Approximate Total Costs > > Without PGTA $ 51,046.50 Embryo Transfer > > With PGTA $ 54,696.50 * Does not include compensation or psychological evaluations. SPP/CD November 2019 | Costs are subject to change The Surrogacy Plan Plus The Surrogacy Plan Plus is available to individuals and couples who want to build a family using a gestational carrrier. In this process, eggs from an egg donor are retrieved and combined with sperm to create embryos. One or two embryos are then transferred into the uterus of the gestational carrier to achieve a pregnancy. How the Surrogacy Plan Plus Works The Surrogacy Plan Plus includes: cycle medication for the oocyte donor and gestational carrier, anesthesia for the retrieval of oocytes, oocyte donor cycle monitoring completed at RMACT, oocyte retrieval, embryology laboratory charges, A simpler approach cryopreservation of embryos, cycle monitoring for the last ultrasound and blood tests to treatment that prior to embryo transfer, embryo transfer into the gestational carrier, and the first year of embryo and specimen storage. If the donor cycle is cancelled prior to retrieval, helps you control the Surrogacy Plan Plus covers the cancellation cost, as well as the cost to rescreen costs with the the same or alternate donor. -

Infertility Services

Medical Policy Assisted Reproductive Services/Infertility Services Document Number: 002 *Commercial and Qualified Health Plans MassHealth Authorization required X No notification or authorization Not covered X *Not all commercial plans cover this service, please check plan’s benefit package to verify coverage. Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Coverage Guidelines ..................................................................................................................................... 2 MassHealth, and Certain Custom Plans ........................................................................................................ 2 Covered Services/Procedures ....................................................................................................................... 3 General Eligibility Coverage Criteria ............................................................................................................. 3 SERVICE -SPECIFIC INFERTILITY COVERAGE FOR MEMBERS WITH UTERI and OVARIES ............................... 5 Artificial Insemination (AI)/Intrauterine Insemination (IUI) ......................................................................... 5 Conversion from IUI to In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) ........................................................................................ 6 In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) for Infertility ....................................................................................................... -

Cryopreserved Oocyte Versus Fresh Oocyte Assisted Reproductive Technology Cycles, United States, 2013

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Fertil Steril Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2018 January 01. Published in final edited form as: Fertil Steril. 2017 January ; 107(1): 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.002. Cryopreserved oocyte versus fresh oocyte assisted reproductive technology cycles, United States, 2013 Sara Crawford, Ph.D.a, Sheree L. Boulet, Dr.P.H., M.P.H.a, Jennifer F. Kawwass, M.D.a,b, Denise J. Jamieson, M.D., M.P.H.a, and Dmitry M. Kissin, M.D., M.P.H.a aDivision of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia bDivision of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia Abstract Objective—To compare characteristics, explore predictors, and compare assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycle, transfer, and pregnancy outcomes of autologous and donor cryopreserved oocyte cycles with fresh oocyte cycles. Design—Retrospective cohort study from the National ART Surveillance System. Setting—Fertility treatment centers. Patient(s)—Fresh embryo cycles initiated in 2013 utilizing embryos created with fresh and cryopreserved, autologous and donor oocytes. Intervention(s)—Cryopreservation of oocytes versus fresh. Main Outcomes Measure(s)—Cancellation, implantation, pregnancy, miscarriage, and live birth rates per cycle, transfer, and/or pregnancy. -

Social Freezing: Pressing Pause on Fertility

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Social Freezing: Pressing Pause on Fertility Valentin Nicolae Varlas 1,2 , Roxana Georgiana Bors 1,2, Dragos Albu 1,2, Ovidiu Nicolae Penes 3,*, Bogdana Adriana Nasui 4,* , Claudia Mehedintu 5 and Anca Lucia Pop 6 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Filantropia Clinical Hospital, 011171 Bucharest, Romania; [email protected] (V.N.V.); [email protected] (R.G.B.); [email protected] (D.A.) 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 37 Dionisie Lupu St., 020021 Bucharest, Romania 3 Department of Intensive Care, University Clinical Hospital, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 37 Dionisie Lupu St., 020021 Bucharest, Romania 4 Department of Community Health, “Iuliu Hat, ieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 6 Louis Pasteur Street, 400349 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 5 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nicolae Malaxa Clinical Hospital, 020346 Bucharest, Romania; [email protected] 6 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Food Safety, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 6 Traian Vuia Street, 020945 Bucharest, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.N.P.); [email protected] (B.A.N.) Abstract: Increasing numbers of women are undergoing oocyte or tissue cryopreservation for medical or social reasons to increase their chances of having genetic children. Social egg freezing (SEF) allows women to preserve their fertility in anticipation of age-related fertility decline and ineffective fertility treatments at older ages. The purpose of this study was to summarize recent findings focusing on the challenges of elective egg freezing. -

Quadrupling Efficiency in Production of Genetically Modified Pigs Through

Quadrupling efficiency in production of genetically PNAS PLUS modified pigs through improved oocyte maturation Ye Yuana,b,1,2,3, Lee D. Spatea,1, Bethany K. Redela, Yuchen Tiana,b, Jie Zhouc, Randall S. Prathera, and R. Michael Robertsa,b,2 aDivision of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211; bBond Life Sciences Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211; and cDepartment of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s Health, University of Missouri School of Medicine, Columbia, MO 65212 Contributed by R. Michael Roberts, May 23, 2017 (sent for review March 15, 2017; reviewed by Marco Conti and Pablo Juan Ross) Assisted reproductive technologies in all mammals are critically Once cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) are removed from the dependent on the quality of the oocytes used to produce embryos. follicular environment and placed into culture, a proportion of the For reasons not fully clear, oocytes matured in vitro tend to be much oocytes usually resume meiosis spontaneously. This promiscuous less competent to become fertilized, advance to the blastocyst stage, progression to metaphase II most probably occurs as the result of a and give rise to live young than their in vivo-produced counterparts, reduced influx of cGMP from the surrounding cumulus cells into particularly if they are derived from immature females. Here we show the oocyte. cGMP maintains high intracellular cAMP concentra- that a chemically defined maturation medium supplemented with tions by inhibiting the phosphodiesterase responsible for cAMP three cytokines (FGF2, LIF, and IGF1) in combination, so-called “FLI hydrolysis (15–17). An inappropriate drop in the concentrations of medium,” improves nuclear maturation of oocytes in cumulus–oocyte the cyclic nucleotides that control meiotic resumption causes un- complexes derived from immature pig ovaries and provides a twofold synchronized nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of the oocytes, increase in the efficiency of blastocyst production after in vitro fertil- thereby compromising their proper development (18). -

In Vitro Maturation of Oocytes Derived from the Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos)

Journal of Reproduction and Development, Vol. 53, No. 3, 2007 —Research Note— In Vitro Maturation of Oocytes Derived from the Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos) Xi-Jun YIN1), Hyo-Sang LEE1), Eu-Gene CHOI1), Xian-Feng YU1), Gye-Young PARK1), Inhyu BAE1), Chul-Ju YANG1), Dong-Hwan OH1), Nam-Hung KIM2) and Il-Keun KONG1) 1)Department of Animal Science and Technology, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, JeonNam 540-742 and 2)Department of Animal Sciences, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Chungbuk 361-763, Korea Abstract. This study was conducted to determine whether meiotic maturation could be induced in ovarian oocytes from the American brown bear (Ursus arctos), a model for gamete “rescue” techniques for endangered ursids. The bears were euthanized, and their ovaries were transported to the laboratory within 4 h. The mean ovarian size was 2.4 × 1.8 cm (range: 2.0–3.3 × 1.5–2.2 cm). The ovaries obtained from the 2 brown bears yielded 97 oocytes (48.5/female), and 88 (90.7%) of them were morphologically classified as normal quality. Oocytes were in vitro matured at 38.5 C in 5% CO2 for 24 or 48 h in TCM-199 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 µg/ml estradiol-17β, and 10 µg/ml FSH. In Exp. 1, morphologic evaluation of matured oocytes was conducted by measuring the diameters of oocytes with a zona pellucida (ZP) or cytoplasm without a ZP. In Exp. 2, activation was induced by applying two 20 µsec DC pulses of 2.0 kV/cm delivered by an Electro Cell Fusion Generator. -

Let She Who Has the Womb Speak: Regulating the Use of Human Oocyte Cryopreservation to the Detriment of Older Women

Arkansas Law Review Volume 72 Number 3 Article 2 February 2020 Let She Who has the Womb Speak: Regulating the use of Human Oocyte Cryopreservation to the Detriment of Older Women Browne C. Lewis Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Browne C. Lewis, Let She Who has the Womb Speak: Regulating the use of Human Oocyte Cryopreservation to the Detriment of Older Women, 72 Ark. L. Rev. 597 (2020). Available at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr/vol72/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LET SHE WHO HAS THE WOMB SPEAK: REGULATING THE USE OF HUMAN OOCYTE CRYOPRESERVATION TO THE DETRIMENT OF OLDER WOMEN Browne C. Lewis INTRODUCTION “Inequality starts in the womb.”1 When it comes to childbearing, advances in assisted reproductive technology (ART) may negate the veracity of this quote. In her autobiography Becoming,2 former First Lady Michelle Obama discusses her struggles with infertility.3 Mrs. Obama’s difficulty getting pregnant may have stemmed from the fact that she postponed motherhood to focus on her career as a high-powered attorney.4 At that time, for Mrs. Obama and women of her generation, the focus was on pregnancy prevention instead of procreation preservation.5 Women feared being placed on the “mommy track,”6 so they waited to have children until after they had achieved success in their careers.7 Some of those women paid B.A., Grambling State University, M.P.P., Humphrey Institute; J.D., University of Minnesota School of Law; University of Houston Law Center. -

Specific Protocols of Controlled Ovarian Stimulation for Oocyte Cryopreservation in Breast Cancer Patients

OVARIAN STIMULATION IN BREAST CANCERORIGINAL PATIENTS, CavagnaARTICLE et al. Specific protocols of controlled ovarian stimulation for oocyte cryopreservation in breast cancer patients † F. Cavagna MD,* A. Pontes MD, M. Cavagna MD,* A. Dzik MD,* N.F. Donadio MD,* R. Portela BSc,* M.T. Nagai MD,* and L.H. Gebrim MD* ABSTRACT Background Fertility preservation is an important concern in breast cancer patients. In the present investigation, we set out to create a specific protocol of controlled ovarian stimulation (cos) for oocyte cryopreservation in breast cancer patients. Methods From November 2014 to December 2016, 109 patients were studied. The patients were assigned to a specific random-start ovarian stimulation protocol for oocyte cryopreservation. The endpoints were the numbers of oocytes retrieved and of mature oocytes cryopreserved, the total number of days of ovarian stimulation, the total dose of gonadotropin administered, and the estradiol level on the day of the trigger. Results Mean age in this cohort was 31.27 ± 4.23 years. The average duration of cos was 10.0 ± 1.39 days. The mean number of oocytes collected was 11.62 ± 7.96 and the mean number of vitrified oocytes was 9.60 ± 6.87. The mean estradiol concentration on triggering day was 706.30 ± 450.48 pg/mL, and the mean dose of gonadotropins administered was 2610.00 ± 716.51 IU. When comparing outcomes by phase of the cycle in which cos was commenced, we observed no significant differences in the numbers of oocytes collected and vitrified, the length of ovarian stimulation, and the estradiol level on trigger day. -

Oocyte Warming and Insemination Consent Form

Oocyte Warming and Insemination Process, Risk, and Consent While embryos and sperm have been frozen and thawed with good results for many years, eggs have proved much more difficult to manage. Newer egg freezing methods have been more successful, at least in younger women, the main population in which the techniques have been studied. Egg freezing takes place by one of two methods: a slow freeze protocol, or a different “flash freeze” method known as vitrification. USF IVF uses the newer vitrification technology exclusively. There are two sources of frozen eggs. Some women may have chosen to have had their eggs frozen for the purpose of fertility preservation at some time prior to warming. Other women may have obtained frozen eggs donated by an egg donor. This consent reviews the Oocyte warming process from start to finish, including the risks that this treatment might pose to you and your offspring. While best efforts have been made to disclose all known risks, there may be risks of oocyte freezing, subsequent warming, and the IVF process, that are not yet clarified or even suspected at the time of this writing. Oocyte warming and subsequent embryo transfer typically includes the following steps or procedures: Medications to prepare the uterus to receive embryos Oocyte warming Insemination of eggs that have survived warming with sperm, using intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) Culture of any resulting fertilized eggs (embryos) Placement (transfer) of one or more embryos into the uterus Support of the uterine lining with hormones to permit and sustain pregnancy In certain cases, these additional procedures can be employed: Assisted hatching of embryos to potentially increase the chance of embryo attachment (implantation) Cryopreservation (freezing) of embryos Is pregnancy achieved as successfully with frozen eggs as with fresh eggs? As mentioned, most studies have looked at success rates using either donor eggs or women who produced larger numbers of eggs.