2/19Th Battalion AIF, 8Th Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

British 8Th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Centre for First World War Studies British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-18 by Alun Miles THOMAS Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law January 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increasingly sophisticated debate take place with regard to the armies on the Western Front during the Great War. Some argue that the British and Imperial armies underwent a ‘learning curve’ coupled with an increasingly lavish supply of munitions, which meant that during the last three months of fighting the BEF was able to defeat the German Army as its ability to conduct operations was faster than the enemy’s ability to react. This thesis argues that 8th Division, a war-raised formation made up of units recalled from overseas, became a much more effective and sophisticated organisation by the war’s end. It further argues that the formation did not use one solution to problems but adopted a sophisticated approach dependent on the tactical situation. -

Malayan Campaign 1941-42 Lessons for ONE SAF

POINTER MONOGRAPH NO. 6 Malayan Campaign 1941-42 Lessons for ONE SAF Brian P. Farrell ■ Lim Choo Hoon ■ Gurbachan Singh ■ Wong Chee Wai EDITORIAL BOARD Advisor BG Jimmy Tan Chairman COL Chan Wing Kai Members COL Tan Swee Bock COL Harris Chan COL Yong Wui Chiang LTC Irvin Lim LTC Manmohan Singh LTC Tay Chee Bin MR Wong Chee Wai MR Kuldip Singh A/P Aaron Chia MR Tem Th iam Hoe SWO Francis Ng Assistant Editor MR Sim Li Kwang Published by POINTER: Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces SAFTI MI 500 Upper Jurong Road Singapore 638364 website: www.mindef.gov.sg/safti/pointer First published in 2008 Copyright © 2008 by the Government of the Republic of Singapore. All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Defence. Body text set in 12.5/14.5 point Garamond Book Produced by touche design CONTENTS About the Authors iv Foreword viii Chapter 1 1 Th e British Defence of Singapore in the Second World War: Implications for the SAF Associate Professor Brian P. Farrell Chapter 2 13 Operational Art in the Malayan Campaign LTC(NS) Gurbachan Singh Chapter 3 30 Joint Operations in the Malayan Campaign Dr Lim Choo Hoon Chapter 4 45 Command & Control in the Malayan Campaign: Implications for the SAF Mr Wong Chee Wai Appendices 62 ABOUT THE AUTHORS ASSOC PROF BRIAN P. FARRELL is the Deputy Head of the Dept. -

April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918)

Some World War I Veterans Connected with Jackson County, Kansas (April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918) A work in progress as of June 27, 2017, by Dan Fenton 1 Some World War I Veterans Connected with Jackson County, Kansas (April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918) Abbott, Carl.1 Carl C. Abbott, private in Company C, 40th Regiment Infantry; enlisted on June 27, 1917, at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri; discharged on March 12, 1918 on account of a physical disability at the Base Hospital, Fort Riley, Kansas. Box 1.10 Carl Clarence Abbott. “OHIO PVT CO C 40 INFANTRY WORLD WAR I” Born May 5, 1898; Died May 12, 1957. Buried in Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery, Akron, Ohio. www.findagrave.com. Abbott, Paul.1 Born in Holton, Kansas, enlisted on September 22, 1917 at Minneapolis, Minnesota; served in France as a private in Company D, 61st Infantry, wounded in right leg. Box 1.10 “August 8, 1918. Dear Mother and kids: I received your letters of July 7 yesterday. It took them just a month to get here. … We have just returned from the trenches to our rest camp, which is about three miles from the trenches. We were about 300 feet from the German trenches, but the only Germans I have seen yet, were some prisoners further inland. The trenches are about a foot above my head at most places, having lookout posts and dugouts at various points. I have been put in an automatic squad. This squad consists of two automatic rifle teams, and the corporal. Each team has one automatic rifleman and two carriers. -

THE LOSS of AMBON FTER Rabaul, Kendari and Balikpapan The

CHAPTER 1 9 THE LOSS OF AMBON FTER Rabaul, Kendari and Balikpapan the next important enemy Aobjective on the eastern flank was Ambon . Initially the Japanese had planned to take it by 6th February, but they had now advanced its plac e on the time-table . As mentioned earlier, Australia had agreed as an outcome of talk s with Netherlands East Indies staffs early in 1941 to hold troops and ai r force squadrons ready at Darwin to reinforce Ambon and Timor if th e Japanese entered the war ; and in consequence, on 17th December, th e 2/21st Battalion landed at Ambon . Part of No. 13 Squadron R.A.A.F., with Hudson bombers, had been established there since 7th December . The 2/21st Battalion, like other units of the 23rd Brigade group, ha d had a frustrating period of service. With other units of the 8th Division , it had been formed soon after the fall of France, and filled with me n eager to go overseas and fight . By March 1941 they had been training for nine months ; yet they were still in Australia . It had been a hard blow to the men of the 2/21st that three junior battalions, trained with the m at Bonegilla, had already sailed abroad. It was a disappointment when , in March, they were ordered to Darwin to spend perhaps the remainder of the war garrisoning an outpost in Australia . Good young leaders sought and obtained transfers to the Armoured Division, and the Indepen- dent Companies then being formed in great secrecy at Foster in Victoria . -

The Malaysian Military Historical Sites

The Military Historical Sites in Malaysia BATTLE OF JITRA BATTLE OF KAMPAR BUKIT KEPONG INCIDENT BATTLE OF MUAR BATTLE OF SLIM RIVER 1 THE BATTLE OF JITRA This is one of the first big scale military engagement between BATTLE OF JITRA the Japanese and British during the Malayan Campaign of the Date 11 - 13 Dec 1941. Location Jitra, British Malaya. Second World War, on 11-13 Dec 1941. Jitra was mainly held Result Japanese victory. by the 11th Indian Division which comprises mainly Indian Beligerents British Indian Division Japan Imperial Army troops. These troops were neither well equipped nor Commanders and leaders prepared and when the Japanese started attacking on 11 Dec MG David Murray-Lyon MG Takuro Matsui Units Involved 1941, they were still setting up traps and communication th th 11 Indian Division 5 Infantry Division systems. Despite this, they still put up a good fight against Casualties and losses 367+ killed 6 tanks destroyed th the well trained Japanese troops. The 11 Indian Division 1 tank damaged was pushed back quickly by the Japanese as they did not have heavy armour and artillery. The Japanese on the other hand had tanks and thus managed to overrun the Indian troops, securing their victory in Jitra. Following that they headed south towards Penang. The Battle of Jitra and the retreat to Gurun had cost the 11th India Division heavily in manpower and strength as an effective fighting force. The division had lost one brigade commander wounded (Brigadier Garrett), one battalion commander killed (Lt Col Bates) and another captured (Lt Col Fitzpatrick). -

Japan's World Heritage Miike Coal Mine

Volume 19 | Issue 13 | Number 1 | Article ID 5605 | Jul 01, 2021 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Japan’s World Heritage Miike Coal Mine – Where prisoners-of- war worked “like slaves” David Palmer English, American, Dutch and Australian. ... We were warned Abstract: Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine is World that our existence in and out of Heritage listed by UNESCO as one of Japan’s camp was governed by a “Sites of the Industrial Revolution.” The multitude of rules and Japanese government, however, has failed to regulations. ... Whenever we met tell the full story of this mine, instead one of the Australians who had promoting bland tourism. In World War II, been in the camp before our Miike was Japan’s largest coal mine, but also arrival and worked in the mine, the location of the largest Allied POW camp in we asked the same questions but Japan. Korean and Chinese forced laborers also could never get an accurate were used by Mitsui in the mine. The use of picture of what the mine was like prisoners was nothing new, as Mitsui and other down below. We only learnt we’d Japanese companies used Japanese convicts as ‘work like slaves’.” workers in the early decades of the Meiji era. The role of Australian POWs in particular reveals that there was resistance inside Miike – Private Roy Whitecross, 8th Division, even at the height of abuse by Japanese Australian Army1 wartime authorities. Japan has a responsibility under its UNESCO World Heritage agreement to tell the full history of this and other “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites. -

Wwii-Text.Pdf

a heritage trail CONTENTS. » northwest » city 01 Sarimbun Beach Landing _________p.3 27 Sook Ching Screening Centre 02 Lim Chu Kang Landing Site ________p.3 (Hong Lim Complex) _____________p.23 03 Ama Keng Village _______________p.4 28 Fort Canning Command Centre ___p.24 04 Tengah Airfield _________________p.4 29 The Cathay _____________________p.25 05 Jurong-Kranji Defence Line _______p.5 30 Kempeitai Headquarters 06 Kranji Beach Battle ______________p.6 (YMCA) _______________________p.26 07 Causeway ______________________p.7 31 Raffles Library & Museum 08 Kranji War Cemetery ____________p.8 (National Museum of Singapore) __p.27 32 Former St. Joseph’s Institution (Singapore Art Museum) _________p.28 » northeast 33 Padang _________________________p.29 09 The Singapore Naval Base ________p.9 34 Municipal Building (City Hall) _____p.29 10 Sembawang Airfield _____________p.11 35 St. Andrew’s Cathedral __________p.29 11 Seletar Airfield__________________p.11 36 Lim Bo Seng Memorial ___________p.30 12 Punggol Beach Massacre Site _____p.12 37 Cenotaph ______________________p.30 13 Japanese Cemetery Park _________p.12 38 Indian National Army Monument _p.30 39 Civilian War Memorial ___________p.31 40 Singapore Volunteer Corps » central Headquarters (Beach Road Camp) p.32 14 Battle for Bukit Timah ____________p.13 41 Kallang Airfield _________________p.32 15 Ford Factory (Memories at Old Ford Factory) ___p.14 16 Bukit Batok Memorial ____________p.15 » east 17 Force 136 & 42. The Changi Museum _____________p.35 Grave of Lim Bo Seng _____________p.16 43. Changi Prison ___________________p.35 44. Johore Battery __________________p.36 45. India Barracks __________________p.37 » south 46. Selarang Barracks _______________p.37 18 Pasir Panjang Pillbox _____________p.17 47. Robert Barracks _________________p.37 19 Kent Ridge Park _________________p.17 48. -

Chapter One- Introduction

Chapter One Introduction The story of the 2118th Battalion AIF begins in Sydney when it was formed as one of the three battalions of the 22nd Brigade, the first brigade of the 8th Division AIF. This thesis traces the battalion's development from its formation in Sydney in 1940 and training in Australia, through its posting to peaceful Malaya as support for the British garrison, the Japanese invasion and, eventually, to the battalion's withdrawal, along with all other Allied troops, to Singapore. The general withdrawal from Malaya signified Japan's victory in the Malayan Campaign. Hindsight clearly reveals that, from a military perspective, the 2118th Battalion's peace time and battle experiences in Malaya were irrelevant to the result of the campaign as well as to subsequent events; consequently, military histories often omit reference to either. From a different standpoint, however, both the social and military experiences of the 2/18th Battalion in Malaya during 1941 and early 1942 do have historical significance. The 22nd Brigade was the first large Australian contingent to go to an Asian country-the soldiers' adaptation to the different conditions and people they encountered is part of Australia's wartime experience. This thesis uses the approach of microhistory to show how the men and officers of the 2118th Battalion interacted in their everyday life, with each other and with the immediate world beyond. It contends that the men of the 2/18th Battalion had their own codes of behaviour and their own agenda according to which they initiated, co-operated or resisted. With discipline and training any military unit will function and in the 2/18th Battalion the discipline never eased. -

English Is the World Language and This Spreads the Influence of the BBC, Reuters and Britain’S Leading Universities

PROGRAM Opening Session 9:30 – 9:35 Opening Remarks Nobushige Takamizawa (President, NIDS) 9:35 – 9:40 Welcoming Remarks Hironori Kanazawa (Administrative Vice-Minister of Defense) 9:40 – 9:50 Chairman’s Remarks Junichiro Shoji (Director, Center for Military History (CMH), NIDS) Keynote Address 9:50 – 10:30 “The Influence and Meaning of the Pacific War in Global History” H.P. Willmott (Honorary Research Associate, Greenwich Maritime Institute, University of Greenwich) 10:30 – 10:45 Break Session 1: Japan and China 10:45 – 11:10 “Reconsideration of Post-War Understanding of Modern Japanese History: An Examination of War and Colonial Rule of Imperial Japan” Fumitaka Kurosawa (Professor, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University) 11:10 – 11:35 “The Pacific War in Modern Chinese History: An Examination of Conflicting Modern Historical Images” Liu Jie (Professor, Waseda University) 11:35 – 12:10 Comment and Discussion Discussant: Haruo Tohmatsu (Professor, National Defense Academy) 12:10 – 13:30 Lunch 121 Session 2: Southeast Asia and Australia 13:30 – 13:55 “Significance of the Pacific War for Southeast Asia” Kyoichi Tachikawa (Chief, Military History Division, CMH, NIDS) 13:55 – 14:20 “Old Enemies, New Friends: Australia and the Impact of the Pacific War” Peter Dennis (Emeritus Professor, The University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy) 14:20 – 14:55 Comment and Discussion Discussant: Hiroshi Noguchi (Associate Professor, Nanzan University) 14:55 – 15:10 Break Session 3: UK and US 15:10 – 15:35 “Churchill’s War; Attlee’s -

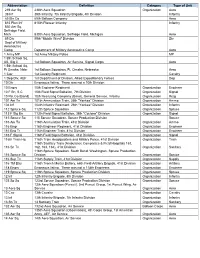

WWI Serviceman Glossary

Abbreviation Definition Category Type of Unit 239 Aer Sq 238th Aero Squadron Organization Aero 39 Inf 39th Infantry, 7th Infantry Brigade, 4th Division Infantry 65 Bln Co 65th Balloon Company Aero 815 Pion Inf 815th Pioneer Infantry Infantry 830 Aer Sq, Selfridge Field, Mich 830th Aero Squadron, Selfridge Field, Michigan Aero 89 Div 89th "Middle West" Division Div Dept of Military Aeronautics Camp Department of Military Aeronautics Camp Aero 1 Army MP 1st Army Military Police MP 1 Bln School Sq, AS, Sig C 1st Balloon Squadron, Air Service, Signal Corps Aero 1 Bln School Sq, Ft Omaha, Nebr 1st Balloon Squadron, Ft. Omaha, Nebraska Aero 1 Cav 1st Cavalry Regiment Cavalry 1 Dep Div, AEF 1st Department of Division, Allied Expeditionary Forces Dep 10 Div Erroneous listing. There was not a 10th Division 10 Engrs 10th Engineer Regiment Organization Engineer 10 F Bn, S C 10th Field Signal Battalion, 7th Division Organization Signal 10 Rct Co (Band) 10th Recruiting Company (Band), General Service, Infantry Organization Rctg 101 Am Tn 101th Ammunition Train, 26th "Yankee" Division Organization Ammo 104 Inf 104th Infantry Regiment, 26th "Yankee" Division Organization Infantry 112 Spruce Sq 112th Spruce Squadron Organization Spruce 113 F Sig Bn 113th Field Signal Battalion, 38th "Cyclone" Division Organization Signal 115 Spruce Sq 115 Spruce Squadron, Spruce Production Division Spruce 116 Am Tn 116th Ammunition Train, 41st Division Organization Ammo 116 Engr 116th Engineer Regiment, 41st Division Organization Engineer 116 Eng Tr 116th Engineer Train,