JRTR No.64 Special Theme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety

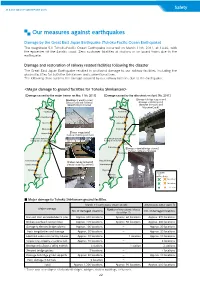

JR EAST GROUP CSR REPORT 2015 Safety Our measures against earthquakes Damage by the Great East Japan Earthquake (Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake) The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Pacific Ocean Earthquake occurred on March 11th, 2011, at 14:46, with the epicenter off the Sanriku coast. Zero customer fatalities at stations or on board trains due to the earthquake. Damage and restoration of railway related facilities following the disaster The Great East Japan Earthquake resulted in profound damage to our railway facilities, including the ground facilities for both the Shinkansen and conventional lines. The following chart outlines the damage incurred by our railway facilities due to the earthquake. <Major damage to ground facilities for Tohoku Shinkansen> 【Damage caused by the major tremor on Mar. 11th, 2011】 【Damage caused by the aftershock on April 7th, 2011】 【Breakage of electric poles】 【Damage to bridge supports and (Between Sendai and Shinkansen breakage of electric poles】 General Rolling Stock Center) (Between Ichinoseki and Mizusawa-Esashi) Shin-Aomori Shin-Aomori Hachinohe Hachinohe Iwate-Numakunai Iwate-Numakunai Morioka Morioka Kitakami Kitakami Ichinoseki 【Track irregularity】 (Sendai Station premises) Ichinoseki Shinkansen General Shinkansen General Rolling Stock Center Rolling Stock Center Sendai Sendai Fukushima Fukushima 【Damage to elevated bridge columns】 (Between Sendai and Furukawa) Kōriyama Kōriyama Nasushiobara Nasushiobara 【Fallen ceiling material】 Utsunomiya (Sendai Station platform) Utsunomiya Oyama Oyama 【Legend】 Ōmiya Ōmiya Civil engineering Tōkyō Tōkyō Electricity 50 locations 10 locations 1 location ■ Major damage to Tohoku Shinkansen ground facilities March 11 earthquake (main shock) Aftershocks (after April 7) Major damage Number of not restored places No. of damaged locations No. -

Chapter 1. Relationships Between Japanese Economy and Land

Part I Developments in Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Administration that Underpin Japan’s Economic Growth ~ Strategic infrastructure management that brings about productivity revolution ~ Section 1 Japanese Economy and Its Surrounding Conditions I Relationships between Japanese Economy and Land, Chapter 1 Chapter 1 Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Administration Relationships between Japanese Economy and Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Administration and Tourism Transport Relationships between Japanese Economy and Land, Infrastructure, Chapter 1, Relationships between Japanese Economy and Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Administration, on the assumption of discussions described in chapter 2 and following sections, looks at the significance of the effects infrastructure development has on economic growth with awareness of severe circumstances surrounding the Japanese economy from the perspective of history and statistical data. Section 1, Japanese Economy and Its Surrounding Conditions, provides an overview of an increasingly declining population, especially that of a productive-age population, to become a super aging society with an estimated aging rate of close to 40% in 2050, and a severe fiscal position due to rapidly growing, long-term outstanding debts and other circumstances. Section 2, Economic Trends and Infrastructure Development, looks at how infrastructure has supported peoples’ lives and the economy of the time by exploring economic growth and the history of infrastructure development (Edo period and post-war economic growth period). In international comparisons of the level of public investment, we describe the need to consider Japan’s poor land and severe natural environment, provide an overview of the stock effect of the infrastructure, and examine its impact on the infrastructure, productivity, and economic growth. -

(News Release) the Results of Radioactive Material Monitoring of the Surface Water Bodies Within Tokyo, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures (September-November Samples)

(News Release) The Results of Radioactive Material Monitoring of the Surface Water Bodies within Tokyo, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures (September-November Samples) Thursday, January 10, 2013 Water Environment Division, Environment Management Bureau, Ministry of the Environment Direct line: 03-5521-8316 Switchboard: 03-3581-3351 Director: Tadashi Kitamura (ext. 6610) Deputy Director: Tetsuo Furuta (ext. 6614) Coordinator: Katsuhiko Sato (ext. 6628) In accordance with the Comprehensive Radiation Monitoring Plan determined by the Monitoring Coordination Meeting, the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) is continuing to monitor radioactive materials in water environments (surface water bodies (rivers, lakes and headwaters, and coasts), etc.). Samples taken from the surface water bodies of Tokyo, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures during the period of September 18-November 16, 2012 have been measured as part of MOE’s efforts to monitor radioactive materials; the results have recently been compiled and are released here. The monitoring results of radioactive materials in surface water bodies carried out to date can be found at the following web page: http://www.env.go.jp/jishin/rmp.html#monitoring 1. Survey Overview (1) Survey Locations 59 environmental reference points, etc. in the surface water bodies within Tokyo, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures (Rivers: 51 locations, Coasts: 8 locations) Note: Starting with this survey, there is one new location (coast). (2) Survey Method ・ Measurement of concentrations of radioactive materials (radioactive cesium (Cs-134 and Cs-137), etc.) in water and sediment ・ Measurement of concentrations of radioactive materials and spatial dose-rate in soil in the surrounding environment of water and sediment sample collection points (river terraces, etc.) 2. -

Hydrological Services in Japan and LESSONS for DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

MODERNIZATION OF Hydrological Services In Japan AND LESSONS FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Foundation of River & Basin Integrated Communications, Japan (FRICS) ABBREVIATIONS ADCP acoustic Doppler current profilers CCTV closed-circuit television DRM disaster risk management FRICS Foundation of River & Basin Integrated Communications, Japan GFDRR Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery ICT Information and Communications Technology JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency JMA Japan Meteorological Agency GISTDA Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency MLIT Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism MP multi parameter NHK Japan Broadcasting Corporation SAR synthetic aperture radar UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Table of Contents 1. Summary......................................................................3 2. Overview of Hydrological Services in Japan ........................................7 2.1 Hydrological services and river management............................................7 2.2 Flow of hydrological information ......................................................7 3. Japan’s Hydrological Service Development Process and Related Knowledge, Experiences, and Lessons ......................................................11 3.1 Relationships between disaster management development and hydrometeorological service changes....................................................................11 3.2 Changes in water-related disaster management in Japan and reQuired -

Towada-Hachimantai National Park Guide Book

Towada-Hachimantai National Park Guide Book 十和田八幡平国立公園 Feel the landscapes of Northern Tohoku that change from season to season in the vast nature 四季それぞれに美しい北東北を自然の中で体感 In Japan, each of the four seasons has its own colour that allows visitors to truly feel its atmosphere. Especially in Tohoku, where winter is crucially rigorous, people wait for the arrival of spring, sing the joys of summer, and appreciate the rich harvests of autumn. There are many things in Tohoku that bring joy to people throughout the year. Towada-Hachimantai National Park is located in the mountainous area of Northern Japan, and lies upon the three prefectures of Northern Tohoku. It is composed of “Towada-Hakkoda Area” , on the northern side that consists of Lake Towada, Oirase Gorge and Hakkoda Mountains and “Hachimantai Area” , on the southern side that consists of Mt. Hachimantai, Mt. Akita-Komagatake and Mt. Iwate. Both areas are very rich in natural resources, such as forests, lakes and marshes, and a wide variety of fauna and flora. There are also many onsen spots where you can immerse your body and soul. 01 Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Hakodate Airport Oma To Tomakomai Aomori Contents ● Tohoku Shinkansen about 3hr 10 min. Tokyo Station Shin-Aomori Station Towada-Hakkoda Area Shin-Aomori Station Airplane about 1hr 20 min. Haneda Airport Misawa Airport Airplane about 1hr 15 min. Haneda Airport Aomori Airport Tohoku Shinkansen about 1hr 30 min. Sendai Station Shin-Aomori Station Hokkaido / Tohoku Shinkansen about 1hr Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Station Shin-Aomori Station Highway Bus about 4hr 50 min. Sendai Station Aomori Station Joy of Spring Iwate 04 春の歓喜 Tohoku Shinkansen about 2hr 20 min. -

Message Board for Disaster (Web 171, Etc.) Disaster Messaging

Information transmission path and collection of information The relationship among the type of evacuation information, your evacuation behavior, the type of flood forecasting of the Arakawa River, and the water level Area where the water will stay for a long time Type and mechanism of flood Urgency Types of evacuation Types of Indication of water levels In the inundation forecast Toda City There are two major types of flood: “river water flood” and Flood forecasting, etc. Evacuation behaviors of the Arakawa River Inland water flood information, etc. Arakawa River Iwabuchi Floodgate (upper) (maximum scale) predicted by “inland water flood.” to be taken by citizens River water ・ Rainwater accumulates issued by the city flood forecasting Gauging Station the MLIT based on the Kawaguchi City River water floodflood at the spot. MLIT/Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)/ High When the risk of human damage ●If you have not evacuated yet, simulation, it is assumed that N This hazard map is Information Kita City, Tokyo Evacuation order becomes extremely high due to evacuate immediately. for ・ There is a rainfall that Tokyo Metropolitan Government Weather, Precipitation, Water level, Arakawa River Flood risk many inundated areas in Kita Burst Video images of rivers, Flood forecasting, Evacuation information, etc. (emergency) a worsened situation such as the ●When conditions outside are dangerous, immediately exceeds sewerage Flood forecasting, etc. Warnings for flood protection, evacuate to a higher place in the building. flood risk water level City will be flooded for not less Sediment disaster alert occurrence of disaster River water flood drainage capacity. information A.P.+7.70m than two weeks. -

A Record of the Reconstruction from March 2011 to March 2019 a Er the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami

IWATE Moving toward Reconstruction A record of the reconstruction from March 2011 to March 2019 aer the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Sanriku Railway Rias Line All parts of the Tohoku East-West Expressway, Kamaishi Akita Line are open. Miyako-Muroran Ferry August 2019 Iwate Kamaishi Unosumai Memorial Stadium Contents Introduction Introduction 1 1 Disaster Damage and the Reconstruction Plan 2 When the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami infrastructures that we could not finish during the initial struck the Tohoku region on the Pacific coast side on March recovery period. We will also promote efforts to Build Back 11, 2011, 5,140 lives were lost in Iwate, primarily on the coast. Better in the Sanriku area, by also taking into account its 2 Status of the Reconstruction 4 I would like to express my sincere condolences to those that future, through supporting mental and emotional care of lost their loved ones, in addition to the families of the 1,114 disaster survivors, providing assistance to form new commu- 3 Support from Abroad 6 people that are still missing. nities, and revitalizing commercial activities in the forestry, With the love and feelings the victims had towards their marine, and agricultural sectors. 4 Main Initiatives So Far hometown firmly in our mind, it became our mission to In addition, as a disaster-affected prefecture, ensure the livelihood as well as the ability to learn and work we can contribute to the improvement of disaster for those affected by the disaster. It also became essential for risk reduction both in Japan and the entire world. -

A Prosperous Future Starts Here

A prosperous future starts here 100% of this paper was made using recycled paper 2018.4 (involved in railway construction) Table of Lines Constructed by the JRTT Contents Tsukuba Tokyo Area Lines Constructed by JRTT… ……………………… 2 Sassho Line Tsukuba Express Line Asahikawa Uchijuku JRTT Main Railway Construction Projects……4 Musashi-Ranzan Signal Station Saitama Railway Line Maruyama Hokkaido Shinkansen Saitama New Urban Musashino Line Tobu Tojo Line Urawa-Misono Kita-Koshigaya (between Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Transit Ina Line Omiya Nemuro Line Shinrin-Koen and Sapporo) ■ Comprehensive Technical Capacity for Railway Sapporo Construction/Research and Plans for Railway Tobu Isesaki Line Narita SKY ACCESS Line Construction… ………………………………………………6 Hatogaya (Narita Rapid Rail Acess Line) Shiki Shin-Matsudo Hokuso Railway Hokuso Line ■ Railway Construction Process… …………………………7 Takenotsuka Tobu Tojo Line Shin-Kamagaya Komuro Shin-Hakodatehokuto Seibu Wako-shi Akabane Ikebukuro Line Imba Nihon-Idai Sekisho Line Higashi-Matsudo Narita Airport Hakodate …… Kotake-Mukaihara Toyo Rapid Construction of Projected Shinkansen Lines 8 Shakujii-Koen Keisei-Takasago Hokkaido Shinkansen Aoto Nerima- Railway Line Nerima Takanodai Ikebukuro Keisei Main Line (between Shin-Aomori and Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto) Hikifune Toyo- Tsugaru-Kaikyo Line Seibu Yurakucho Line Tobu Katsutadai ■ Kyushu Shinkansen… ………………………………………9 Tachikawa Oshiage Ueno Isesaki Line Keio Line Akihabara Nishi-Funabashi Shinjuku … ………………………………… Odakyu Odawara Line Sasazuka ■ Hokuriku Shinkansen 10 Yoyogi-Uehara -

Sanriku Railway Restored to Glory

The news from Iwate as it moves toward reconstruction We are deeply grateful for the heartwarming encouragement and News from Iwate’s Reconstruction support received from both within and outside of Japan in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, which Ganbaro, Iwate! struck on March 11, 2011. The precious bonds created during this time Volume 61 will always be cherished. Let’s stick together, Iwate! (April 2014) The snow on the ground has melted, and after a long, cold winter we are finally moving into spring. Iwate Prefecture We will now bring you the news from Iwate’s reconstruction. Sanriku Railway Restored To Glory Sanriku Railway, which serves dual roles as a transportation system for the residents of Iwate’s coastal region and a key part of the region’s tourism sector, suffered significant damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. After the disaster, the portions of the railway that had suffered only minor damage were quickly able to resume operations , but it was not until April 6 of this year, a full three years after the disaster, that the whole line was rebuilt and trains could once again run on the full 107.6-km stretch of rail. Sugimoto and Arakawa “split the ball” (kusudama-wari) at the Kuji ceremony We hope that Sanriku Railway will serve as a symbol of Iwate’s Operation of North Rias Line Resumes reconstruction. The following day (April 6) saw the resumption of operations of the Operation of South Rias Line Resumes North Rias Line’s 10.5-km stretch between Omoto and Tanohata On April 5, the 15-km stretch between Kamaishi and Yoshihama stations. -

Connecting Sanriku, Connecting People

Series Topics Shimanokoshi Station was relocated and The Sanriku Railway also stops at Horinai Station, which has rebuilt after it washed away in the tsunami an elevated platform to help prevent damage from tsunami caused by the earthquake Connecting Sanriku, Connecting People The Sanriku Railway resumed limited operations just five days after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and had restored all the rail lines in the north and south sections by 2014. In March 2019, a new line will connect the ends of KATSUMI YASUKURA the north and south—Kamaishi and Miyako—covering the entire Sanriku area in Iwate Prefecture. Two railroad men share their stories of the challenges involved in restoring train operations and passing down memories of the aftermath. N March 11, 2011, says. “Our company president steadily recovered, the Sanriku the Great East decided that we had to restart Railway must have given hope to Japan Earthquake the trains as soon as possible, those struggling to rebuild their devastated the Pacific understanding that they were lives after the earthquake. Ocoast of the Tohoku region. looking for people and to obtain In 2013, the popularity of Just five days after the quake, necessary items but couldn’t use national public broadcaster however, the Sanriku Railway the national highways, which NHK’s TV drama Ama-chan, in Iwate Prefecture had restored had been buried in debris. So we which was set in areas along service between Rikuchunoda ran free train services as a part of the Sanriku Railway lines, and Kuji stations on the North reconstruction assistance.” boosted the number of visitors. -

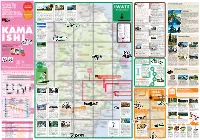

Access Guide Map KAMAISHI

UNESCO World Heritage A B C D E 7 Taro Coastal Barrier E-3 1 2 3 Earthquake Sanriku Geopark Originally seen as a symbol of disaster World Geoparks are places that allow visitors to learn about the Earth in a fun manner. Here Heritage Educational preparedness and referred to as “The Candidate Great Wall,” this barrier was completely we will introduce a number of natural assets in the Sanriku Geopark that were formed Facilities overrun by the tsunami. over the course of millennia. Visitors can gain new perspectives about our planet The Earthquake Education Network through geological science and geography. IWATE E-4 Council has 192 registered earth- 8 Tsunami Memorial Park NAKANOHAMA Prefecture quake educational facilities (as of 1 Beauty Spots that Define Sanriku orld E-2 E-3 O W He Kosode Ama Center Kitayamazaki March, 2019). These facilities aim to Originally a coastal campsite, some of the E-4 C ri Jodogahama ES ta Reopened in Spring 2015 af- Provides spectacular views destroyed facilities have been preserved g C-2 preserve the memories and records of This scenery was created through 40 million years of N e Goshono Site ter the previous facility was of 200m tall cliffs that stretch as part of this park. U the Great East Japan Earthquake and magma activity and wave erosion. Visitors can enjoy This area contains the remains of a large settle- destroyed during the Great for 8km from Kurosaki to N tsunami. The "Type 3" facilities work to this unique site from pleasure boats and small fish- ment from about 4,000 years ago. -

METROS/U-BAHN Worldwide

METROS DER WELT/METROS OF THE WORLD STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 ّ :جمهورية مرص العرب ّية/ÄGYPTEN/EGYPT/DSCHUMHŪRIYYAT MISR AL-ʿARABIYYA :القاهرة/CAIRO/AL QAHIRAH ( حلوان)HELWAN-( المرج الجديد)LINE 1:NEW EL-MARG 25.12.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmr5zRlqvHY DAR EL-SALAM-SAAD ZAGHLOUL 11:29 (RECHTES SEITENFENSTER/RIGHT WINDOW!) Altamas Mahmud 06.11.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6xG3hZccyg EL-DEMERDASH-SADAT (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 12:29 Mahmoud Bassam ( المنيب)EL MONIB-( ش ربا)LINE 2:SHUBRA 24.11.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UCJA6bVKQ8 GIZA-FAYSAL (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 02:05 Bassem Nagm ( عتابا)ATTABA-( عدىل منصور)LINE 3:ADLY MANSOUR 21.08.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7m5Z9g39ro EL NOZHA-ADLY MANSOUR (FENSTERBLICKE/WINDOW VIEWS!) 03:49 Hesham Mohamed ALGERIEN/ALGERIA/AL-DSCHUMHŪRĪYA AL-DSCHAZĀ'IRĪYA AD-DĪMŪGRĀTĪYA ASCH- َ /TAGDUDA TAZZAYRIT TAMAGDAYT TAỴERFANT/ الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطيةالشعبية/SCHA'BĪYA ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ : /DZAYER TAMANEỴT/ دزاير/DZAYER/مدينة الجزائر/ALGIER/ALGIERS/MADĪNAT AL DSCHAZĀ'IR ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵏⴻⵖⵜ PLACE DE MARTYRS-( ع ني نعجة)AÏN NAÂDJA/( مركز الحراش)LINE:EL HARRACH CENTRE ( مكان دي مارت بز) 1 ARGENTINIEN/ARGENTINA/REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA: BUENOS AIRES: LINE:LINEA A:PLACA DE MAYO-SAN PEDRITO(SUBTE) 20.02.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfUmJPEcBd4 PIEDRAS-PLAZA DE MAYO 02:47 Joselitonotion 13.05.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lJAhBo6YlY RIO DE JANEIRO-PUAN 07:27 Así es BUENOS AIRES 4K 04.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoUNwMT2DoI