Angraecum Sesquipedale ET

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Repair and Self-Cleaning of the Lepidopteran Proboscis

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 8-2019 Self-Repair and Self-Cleaning of the Lepidopteran Proboscis Suellen Floyd Pometto Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Pometto, Suellen Floyd, "Self-Repair and Self-Cleaning of the Lepidopteran Proboscis" (2019). All Dissertations. 2452. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/2452 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SELF-REPAIR AND SELF-CLEANING OF THE LEPIDOPTERAN PROBOSCIS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ENTOMOLOGY by Suellen Floyd Pometto August 2019 Accepted by: Dr. Peter H. Adler, Major Advisor and Committee Co-Chair Dr. Eric Benson, Committee Co-Chair Dr. Richard Blob Dr. Patrick Gerard i ABSTRACT The proboscis of butterflies and moths is a key innovation contributing to the high diversity of the order Lepidoptera. In addition to taking nectar from angiosperm sources, many species take up fluids from overripe or sound fruit, plant sap, animal dung, and moist soil. The proboscis is assembled after eclosion of the adult from the pupa by linking together two elongate galeae to form one tube with a single food canal. How do lepidopterans maintain the integrity and function of the proboscis while foraging from various substrates? The research questions included whether lepidopteran species are capable of total self- repair, how widespread the capability of self-repair is within the order, and whether the repaired proboscis is functional. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae): Evidence from Five Nuclear Genes

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae): Evidence from Five Nuclear Genes Akito Y. Kawahara1*, Andre A. Mignault1, Jerome C. Regier2, Ian J. Kitching3, Charles Mitter1 1 Department of Entomology, College Park, Maryland, United States of America, 2 Center for Biosystems Research, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, College Park, Maryland, United States of America, 3 Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom Abstract Background: The 1400 species of hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) comprise one of most conspicuous and well- studied groups of insects, and provide model systems for diverse biological disciplines. However, a robust phylogenetic framework for the family is currently lacking. Morphology is unable to confidently determine relationships among most groups. As a major step toward understanding relationships of this model group, we have undertaken the first large-scale molecular phylogenetic analysis of hawkmoths representing all subfamilies, tribes and subtribes. Methodology/Principal Findings: The data set consisted of 131 sphingid species and 6793 bp of sequence from five protein-coding nuclear genes. Maximum likelihood and parsimony analyses provided strong support for more than two- thirds of all nodes, including strong signal for or against nearly all of the fifteen current subfamily, tribal and sub-tribal groupings. Monophyly was strongly supported for some of these, including Macroglossinae, Sphinginae, Acherontiini, Ambulycini, Philampelini, Choerocampina, and Hemarina. Other groupings proved para- or polyphyletic, and will need significant redefinition; these include Smerinthinae, Smerinthini, Sphingini, Sphingulini, Dilophonotini, Dilophonotina, Macroglossini, and Macroglossina. The basal divergence, strongly supported, is between Macroglossinae and Smerinthinae+Sphinginae. All genes contribute significantly to the signal from the combined data set, and there is little conflict between genes. -

Pollination and Botanic Gardens Contribute to the Next Issue of Roots

Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 17 • Number 1 • May 2020 Pollination and botanic gardens Contribute to the next issue of Roots The next issue of Roots is all about education and technology. As this issue goes to press, most botanic gardens around the world are being impacted by the spread of the coronavirus Covid-19. With many Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 16 • Number 2 • October 2019 Citizen gardens closed to the public, and remote working being required, Science educators are having to find new and innovative ways of connecting with visitors. Technology is playing an ever increasing role in the way that we develop and deliver education within botanic gardens, making this an important time to share new ideas and tools with the community. Have you developed a new and innovative way of engaging your visitors through technology? Are you using technology to engage a Botanic Gardens Conservation International Education Review Volume 17 • Number 1 • April 2020 wider audience with the work of your garden? We are currently looking for a variety of contributions including Pollination articles, education resources and a profile of an inspirational garden and botanic staff member. gardens To contribute, please send a 100 word abstract to [email protected] by 15th June 2020. Due to the global impacts of COVID-19, BGCI’s 7th Global Botanic Gardens Congress is being moved to the Australian spring. Join us in Melbourne, 27 September to 1 October 2021, the perfect time to visit Victoria. Influence and Action: Botanic Gardens as Agents of Change will explore how botanic gardens can play a greater role in shaping our future. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Amphiesmeno- Ptera: the Caddisflies and Lepidoptera

CY501-C13[548-606].qxd 2/16/05 12:17 AM Page 548 quark11 27B:CY501:Chapters:Chapter-13: 13Amphiesmeno-Amphiesmenoptera: The ptera:Caddisflies The and Lepidoptera With very few exceptions the life histories of the orders Tri- from Old English traveling cadice men, who pinned bits of choptera (caddisflies)Caddisflies and Lepidoptera (moths and butter- cloth to their and coats to advertise their fabrics. A few species flies) are extremely different; the former have aquatic larvae, actually have terrestrial larvae, but even these are relegated to and the latter nearly always have terrestrial, plant-feeding wet leaf litter, so many defining features of the order concern caterpillars. Nonetheless, the close relationship of these two larval adaptations for an almost wholly aquatic lifestyle (Wig- orders hasLepidoptera essentially never been disputed and is supported gins, 1977, 1996). For example, larvae are apneustic (without by strong morphological (Kristensen, 1975, 1991), molecular spiracles) and respire through a thin, permeable cuticle, (Wheeler et al., 2001; Whiting, 2002), and paleontological evi- some of which have filamentous abdominal gills that are sim- dence. Synapomorphies linking these two orders include het- ple or intricately branched (Figure 13.3). Antennae and the erogametic females; a pair of glands on sternite V (found in tentorium of larvae are reduced, though functional signifi- Trichoptera and in basal moths); dense, long setae on the cance of these features is unknown. Larvae do not have pro- wing membrane (which are modified into scales in Lepi- legs on most abdominal segments, save for a pair of anal pro- doptera); forewing with the anal veins looping up to form a legs that have sclerotized hooks for anchoring the larva in its double “Y” configuration; larva with a fused hypopharynx case. -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

Feeding Mechanisms of Adult Lepidoptera: Structure, Function, and Evolution of the Mouthparts

ANRV397-EN55-17 ARI 2 November 2009 12:12 Feeding Mechanisms of Adult Lepidoptera: Structure, Function, and Evolution of the Mouthparts Harald W. Krenn Department of Evolutionary Biology, University of Vienna, A 1090 Vienna, Austria; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010. 55:307–27 Key Words The Annual Review of Entomology is online at proboscis, fluid uptake, flower visiting, feeding behavior, insects ento.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085338 The form and function of the mouthparts in adult Lepidoptera and Copyright c 2010 by Annual Reviews. their feeding behavior are reviewed from evolutionary and ecological All rights reserved points of view. The formation of the suctorial proboscis encompasses a 0066-4170/10/0107-0307$20.00 fluid-tight food tube, special linking structures, modified sensory equip- Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010.55:307-327. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org by University of Vienna - Central Library for Physics on 12/07/09. For personal use only. ment, and novel intrinsic musculature. The evolution of these function- ally important traits can be reconstructed within the Lepidoptera. The proboscis movements are explained by a hydraulic mechanism for un- coiling, whereas recoiling is governed by the intrinsic proboscis mus- culature and the cuticular elasticity. Fluid uptake is accomplished by the action of the cranial sucking pump, which enables uptake of a wide range of fluid quantities from different food sources. Nectar-feeding species exhibit stereotypical proboscis movements during flower han- dling. Behavioral modifications and derived proboscis morphology are often associated with specialized feeding preferences or an obligatory switch to alternative food sources. -

Structure of the Lepidopteran Proboscis in Relation to Feeding Guild

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 00:00–00 (2015) Structure of the Lepidopteran Proboscis in Relation to Feeding Guild Matthew S. Lehnert,1,2* Charles E. Beard,2 Patrick D. Gerard,3 Konstantin G. Kornev,4 and Peter H. Adler2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University at Stark, North Canton, Ohio 44720 2Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 3Department of Mathematical Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 4Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 ABSTRACT Most butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) (Monaenkova et al., 2012). A pump in the head use modified mouthparts, the proboscis, to acquire flu- then forces the liquid up the food canal to the gut ids. We quantified the proboscis architecture of five (Eberhard and Krenn, 2005; Borrell and Krenn, butterfly species in three families to test the hypothesis 2006; Lee et al., 2014). that proboscis structure relates to feeding guild. We Feeding guilds (i.e., groups of species with simi- used scanning electron microscopy to elucidate the fine structure of the proboscis of both sexes and to quantify lar feeding habits) have long been recognized in dimensions, cuticular patterns, and the shapes and the Lepidoptera and have been associated with sizes of sensilla and dorsal legulae. Sexual dimorphism higher taxa, such as nymphalid subfamilies or was not detected in the proboscis structure of any spe- tribes (Gilbert and Singer, 1975; Krenn et al., cies. A hierarchical clustering analysis of overall pro- 2001). Adult Lepidoptera are conventionally cate- boscis architecture reflected lepidopteran phylogeny, gorized into at least two broad feeding guilds: but did not produce a distinct group of flower visitors flower visitors (nectar feeders) and nonflower visi- or of puddle visitors within the flower visitors. -

Les Sphingidae, Probables Pollinisateurs Des

Les Sphingidae, probables pollinisateurs des baobabs malgaches Philippe Ryckewaert, Onja Razanamaro, Elysée Rasoamanana, Tantelinirina Rakotoarimihaja, Perle Ramavovololona, Pascal Danthu To cite this version: Philippe Ryckewaert, Onja Razanamaro, Elysée Rasoamanana, Tantelinirina Rakotoarimihaja, Perle Ramavovololona, et al.. Les Sphingidae, probables pollinisateurs des baobabs malgaches. Cirad. Bois et forêts des tropiques, Bois et Forêts des Tropiques, pp.56-68, 2011, 307 (1). cirad-00848889 HAL Id: cirad-00848889 http://hal.cirad.fr/cirad-00848889 Submitted on 29 Jul 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BOIS ET FORÊTS DES TROPIQUES, 2011, N° 307 (1) 55 POLLINISATION / LE POINT SUR… Les Sphingidae, probables pollinisateurs des baobabs malgaches Philippe Ryckewaert1 Onja Razanamaro2, 3 Elysée Rasoamanana2, 3 Tantelinirina Rakotoarimihaja2, 4 Perle Ramavovololona2, 3 Pascal Danthu2, 5 1 Cirad Upr Hortsys Campus international de Baillarguet 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5 France 2 Cirad Urp Forêts et biodiversité BP 853, Antananarivo Madagascar 3 Université d’Antananarivo Faculté des Sciences Département de biologie et écologie végétales BP 906, Antananarivo (101) Madagascar 4 Université d’Antananarivo Faculté des Sciences Département de biologie animale BP 906, Antananarivo (101) Madagascar 5 Cirad Upr B&Sef Campus international de Baillarguet 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5 France Photo 1. -

Check List 4(2): 123–136, 2008

Check List 4(2): 123–136, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Light-attracted hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) of Boracéia, municipality of Salesópolis, state of São Paulo, Brazil. Marcelo Duarte 1 Luciane F. Carlin 1 Gláucia Marconato 1, 2 1 Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo. Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, CEP 04263-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Curso de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia), Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo. Rua do Matão, travessa 14, número 321. CEP 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Abstract: The light-attracted hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) of the Estação Biológica de Boracéia, municipality of Salesópolis, state of São Paulo, Brazil were sampled during a period of 64 years (1940-2004). A total of 2,064 individuals belonging to 3 subfamilies, 6 tribes, 23 genera and 75 species were identified. Macroglossinae was the most abundant and richest subfamily in the study area, being followed by Sphinginae and Smerinthinae. About 66 % of the sampled individuals were assorted to the macroglossine tribes Dilophonotini and Macroglossini. Dilophonotini (Macroglossinae) was the richest tribe with 26 species, followed by Sphingini (Sphinginae) with 18 species, Macroglossini (Macroglossinae) with 16 species, Ambulycini (Smerinthinae) and Philampelini (Macroglossinae) with seven species each one, and Acherontiini (Sphinginae) with only one species. Manduca Hübner (Sphinginae) and Xylophanes Hübner (Macroglossinae) were the dominant genera in number of species. Only Xylophanes thyelia thyelia (Linnaeus) and Adhemarius eurysthenes (R. Felder) were recorded year round Introduction Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) comprise Kitching 2002). Because of their capability to fly about 200 genera and 1300 species (Kitching and far away, these moths are potential long distance Cadiou 2000). -

Orchids and Their Pollinators

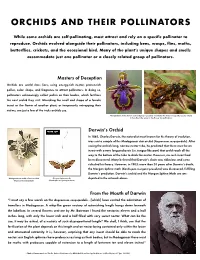

ORCHIDS AND THEIR POLLINATORS While some orchids are self-pollinating, most attract and rely on a specific pollinator to reproduce. Orchids evolved alongside their pollinators, including bees, wasps, flies, moths, butterflies, crickets, and the occasional bird. Many of the plant’s unique shapes and smells accommodate just one pollinator or a closely related group of pollinators. Masters of Deception Orchids are world class liars, using energy-rich nectar, protein-rich pollen, color, shape, and fragrance to attract pollinators. In doing so, pollinators unknowingly collect pollen on their bodies, which fertilizes the next orchid they visit. Mimicking the smell and shape of a female insect or the flower of another plant, or temporarily entrapping their victims, are just a few of the tricks orchids use. The labellum of the mirror orchid (Ophrys speculum) resembles the female wasp (Dasyscolia ciliata) to lure the male wasp to the flower for pollination. Darwin’s Orchid In 1862, Charles Darwin, the naturalist most known for his theory of evolution, was sent a sample of the Madagascar star orchid (Angraecum sesquipedale). After seeing the orchids long, narrow nectar tube, he predicted that there must be an insect with a very long proboscis (i.e. tongue-like part) that could reach all the way to the bottom of the tube to drink the nectar. However, no such insect had been discovered. Many believed that Darwin’s claim was ridiculous and some ridiculed his theory. However, in 1903, more than 20 years after Darwin’s death, the Morgan Sphinx moth (Xanthopan morganii praedicta) was discovered, fulfilling Darwin’s prediction.