Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

23 East African Railways and Harbours Administration

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Washing%on, D.C. ast Africa High Commission November 29, 195 (2) East African Railways and Harbours Administration Mr. Walter S. Rogers Institute of Current World Affairs 22 Fifth Avenue New York 6, New York Dear Mr. Rogers The public Railways and Inland Marine Service of ast Africa, a] oerated by the Railways and Harbours Administration, are by far the rlncipal means of transport of the area. In 1992 they performed some I,98,60,O ton miles of freight haulage and some 6,,898 passenger orneys over ,O99 route miles of metre gauge railway and other routes. The present role of the railway is varie. At the outlying pointB it is rovidlng access to new agrlc,tural areas and to mineral operations. Along established lines it continues to bring in the capital equipment for development and the import goods in demand by the uropean, Asian and African population; but it also is serving increasingly as an economic integrator, allowing regional agricultural specialization so that each smal bloc of territory ned not remain fully self sufficient in food grains. The comparatively cheap*haulage to the coast of larger quantities of export produce, sisal, cotton, coffee, sod-ash, is a necessary facility for the expanding economy of .East Africa. The railway also gives mobility to labor in ast Africa, facilitating the migrations necessary for agricultural purposes and for industries denendent upon large numbers of African personnel. By providing longer heavier haulge services, the railways complement their own and other motor transport service; the natural difficulties of road building and maintanance being formidable in East Africa, it is usually accepted that truck haulage routes should be ancilary to the railway. -

Kigoma Airport

The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for the Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Preliminary Design Report Environmental Impact Assessment July 2008 In Association With : Sir Frederick Snow & Partners Ltd Belva Consult Limited Corinthian House, PO Box 7521, Mikocheni Area, 17 Lansdowne Road, Croydon, Rose Garden Road, Plot No 455, United Kingdom CR0 2BX, UK Dar es Salaam Tel: +44(02) 08604 8999 Tel: +255 22 2120447 Fax: +44 (02)0 8604 8877 Email: [email protected] Fax: +255 22 2120448 Web Site: www.fsnow.co.uk Email: [email protected] The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for the Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Preliminary Design Report Environmental Impact Assessment Prepared by Sir Frederick Snow and Partners Limited in association with Belva Consult Limited Issue and Revision Record Rev Date Originator Checker Approver Description 0 July 08 Belva KC Preliminary Submission EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction The Government of Tanzania through the Tanzania Airports Authority is undertaking a feasibility study and detailed engineering design for the rehabilitation and upgrading of the Kigoma airport, located in Kigoma-Ujiji Municipality, Kigoma region. The project is part of a larger project being undertaken by the Tanzania Airport Authority involving rehabilitation and upgrading of high priority commercial airports across the country. The Tanzania Airport Authority has commissioned two companies M/S Sir Frederick Snow & Partners Limited of UK in association with Belva Consult Limited of Tanzania to undertake a Feasibility Study, Detail Engineering Design, Preparation of Tender Documents and Environmental and Social Impact Assessments of seven airports namely Arusha, Bukoba, Kigoma, Tabora, Mafia Island, Shinyanga and Sumbawanga. -

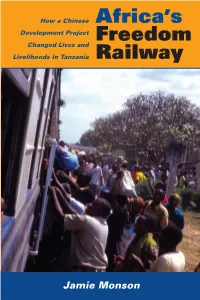

Africa's Freedom Railway

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

Rail Transport and Firm Productivity: Evidence from Tanzania

WPS8173 Policy Research Working Paper 8173 Public Disclosure Authorized Rail Transport and Firm Productivity Evidence from Tanzania Public Disclosure Authorized Atsushi Iimi Richard Martin Humphreys Yonas Eliesikia Mchomvu Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Transport and ICT Global Practice Group August 2017 Policy Research Working Paper 8173 Abstract Railway transport generally has the advantage for large-vol- Rail transport is a cost-effective option for firms. How- ume, long-haul freight operations. Africa possesses ever, the study finds that firms’ inventory is costly. This significant railway assets. However, many rail lines are cur- is a disadvantage of using rail transport. Rail operations rently not operational because of the lack of maintenance. are unreliable, adding more inventory costs to firms. The The paper recasts light on the impact of rail transportation implied elasticity of demand for transport services is esti- on firm productivity, using micro data collected in Tanza- mated at −1.01 to −0.52, relatively high in absolute terms. nia. To avoid the endogeneity problem, the instrumental This indicates the rail users’ sensitivity to prices as well as variable technique is used to estimate the impact of rail severity of modal competition against truck transportation. transport. The paper shows that the overall impact of rail The study also finds that firm location matters to the deci- use on firm costs is significant despite that the rail unit sion to use rail services. Proximity to rail infrastructure rates are set lower when the shipping distance is longer. is important for firms to take advantage of rail benefits. This paper is a product of the Transport and ICT Global Practice Group. -

Comprehensive Transport and Trade System Development Master Plan in the United Republic of Tanzania

Ministry of Transport, The United Republic of Tanzania Comprehensive Transport and Trade System Development Master Plan in the United Republic of Tanzania – Building an Integrated Freight Transport System – Final Report Volume 4 Pre-Feasibility Studies March 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY PADECO Co., Ltd. Nippon Koei Co. Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Incorporated EI JR 14-068 Note: In this study, the work for Master Plan Formulation and Pre-Feasibility Study was completed at the end of 2012 and a Draft Final Report was issued. This final report incorporates comments on the draft final report received from various concerned parties. In accordance with Tanzanian Laws, the process of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) was carried out after the issuance of the Draft Final Report in order to allow for the study to be officially recognized as a Master Plan. The results of the one year SEA have been incorporated in this report. The report contains data and information available at the end of 2012 and does not reflect changes which have taken place since then, except for notable issues and those related to the SEA. Comprehensive Transport and Trade System Development Final Report Master Plan in the United Republic of Tanzania Volume 4 Pre-Feasibility Studies Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Selection of Projects Subject to Pre-Feasibility Study ................................................ 1 1.1.1 -

The United Republic of Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for The Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Final Design Report Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment November 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized In Association With: Sir Frederick Snow & Partners Ltd Belva Consult Limited Corinthian House, PO Box 7521, Mikocheni Area, 17 Lansdowne Road, Croydon, January 2008 Rose Garden Road, Plot No 455, United Kingdom CR0 2BX, UK Dar es Salaam Tel: +44(02) 08604 8999 Tel: +255 22 2775910 Fax: +44 (02)0 8604 8877 Email: [email protected] Fax: +255 22 2775919 Web Site: www.fsnow.co.uk Email: [email protected] The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for the Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Final Design Report Environmental Impact Assessment Prepared by Sir Frederick Snow and Partners Limited in association with Belva Consult Limited Issue and Revision Record Rev Date Originator Checker Approver Description 0 July 08 Belva KC Preliminary Submission 1 Mar 09 Belva KC Final Draft Submission 2 Nov 09 Belva KC Re-scoping Submission EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction The Government of Tanzania through the Tanzania Airports Authority is undertaking a feasibility study and detailed engineering design for the rehabilitation and upgrading of the Kigoma airport, located in Kigoma-Ujiji Municipality, Kigoma region. The project is part of a larger project being undertaken by the Tanzania Airport Authority involving rehabilitation and upgrading of high priority commercial airports across the country. -

Tanzania Railways Limited (Trl)

TANZANIA RAILWAYS LIMITED (TRL) PRIORITY PROJECTS FOR FUNDING MARCH, 2016 Ministry MINISTRY OF WORK, TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATION Project Code 4292 Project Name REVITALIZATION OF TANZANIA RAILWAYS LIMITED (TRL) Project Procurement and Repair of Rolling Stock to increase capacity Objective of operating equipment and improve availability. Project owner Tanzania Railways Limited through the Government of (Implementing Tanzania (GOT) Authority) Location: Throughout the Tanzania Railways system with 2,707 kms of track running east to west (central corridor) and passing through seven regions i.e Dar es Salaam. Coast, Morogoro, Dodoma, Singida, Tabora and Shinyanga also Kigoma and Katavi. Short The project is intended to revamp railway operations of the Description central line to Kigoma and Mwanza by increasing haulage capacity of passengers and freight traffic within the country and neighboring countries of Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Eastern part of DRC. Project Railways capacity to haul large volumes including bulky Benefits traffic lowers unit cost of transportation thereby enabling sellers to set low prices to last consumers thereby contribute to poverty reduction. Increased railway throughput will reduce road transport requirement which will save the Government the cost of construction/maintaining roads. It will provide easy accessibility to various social services to the community along the project area. Enable trade facilitation between Tanzania and neighboring countries of DRC, Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda. Increase in number and -

Trends in Rail Transport in Zambia and Tanzania

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Trends in Rail Transport in Zambia and Tanzania John F. Due Professor of Economics" Ut4fiti Vol VIII No.2, 1986, Journal University of Illinois of the FacUlty of Arts and Social Sciences Urbana - Champaign University of Oar es Sal~ , Rail tr~sport in Africa began in the colonial days. The lines were built partly for milItary reasons and partly to allow exploitation of mineral deposits, export of farm products, and import of manufactured goods. Built inland from the coast, they were not designed for inter-country trade nor were they ideal' 'for internal economic development. They were built cheaply, and to a narrow gauge of 1.067 meters (3 Y2feet) in the British colonies (but not in all) and I meter in most others. After independence one major line (Tazara) was built, some ,lines were extended, and some connecting links built. On the whole, however, despite some improvements, hi manyrespectsmost systems have de- teriorated in recent decades. Itis the purpose of this paper to review the recent expsrience in detail in Zambia and Tanzania Zambia Railways Much of Zambia has never had rail service. The Zambia Railway ..: line was built by Rhodesian Railways, crossmg the Zambezi at Victoria Falls nearLiviIIg- stone in l~3, reaching Kabwe (then Broken Hill) in 1906,'andCopper Belt (then little deveioped) In 1909. -

United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Transport

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED TANZANIA INTERMODAL AND RAIL PROJECT (TIRP) REHABILITATION OF RAILWAY LINE INCLUDING TRACK RENEWAL AND BRIDGES UPGRADING BETWEEN DAR ES SALAAM AND ISAKA ALONG THE CORE CORRIDOR TO MWANZA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Prepared by Juma Kayonko, MSc Registered Environmental Expert (NEMC/EIA 0162), P.O. Box 30, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Mobile: (+255) 0787/0754 616 700 Email: [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized NOVEMBER 2013 REHABILITATION OF RAILWAY LINE INCLUDING TRACK RENEWAL AND BRIDGES UPGRADING BETWEEN DAR ES SALAAM AND ISAKA ALONG THE CORE CORRIDOR TO MWANZA ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Juma Kayonko, MSc Registered Environmental Expert (NEMC/EIA 0162), P.O. Box 30, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Mobile: (+255) 0787/0754 616700 Email: [email protected] NOVEMBER 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ______________________________________________________ ii List of Tables __________________________________________________________ vi List of Figures _________________________________________________________ vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ________________________________________ viii Acknowledgement ____________________________________________________ ix Executive Summary ____________________________________________________ x Chapter 1: Introduction ________________________________________________ 1 1.1 General Background -

World Bank Document

OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PLANNING Telegrams: "TREASURY", Dar es 1 Madaraka Street, Salaam, Tel: 2111174/6, Fax 2110326.Fax P.O. Box 9111, 41329 11468 DAR ES SALAAM; Public Disclosure Authorized Email: PJ@r nofgOt, Website: wvw.mof.go.tz TANZANIA, (All Official communications should be addressed to the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury and NOT to individuals). In reply please quote: Ref. No. CDB 340/441/01 May 31, 2017 Country Director for Tanzania, Burundi, Malawi and Somalia, World Bank Country Office, 50 Mirambo Street, DAR ES SALAAM. Public Disclosure Authorized RE: LETTER OF DEVELOPMENT POLICY FOR THE DAR ES SALAAM MARITIME GATEWAY PROJECT 1. Background The United Republic of Tanzania is the largest country in the East African Region with a land area of 947,000 square kilometres and 1,424km coastline along the Indian Ocean. It has a population of about 45 million people (census, 2012), spread throughout the country with particular concentration in Dar es Salaam. The Geographic and demographic facts of the country require a strong and well operated integrated transport system to support economic and social development Public Disclosure Authorized in the country. The transport system in Tanzania comprises a road network of over 87,000 km, a railway network of about 3,677 km of trunk lines, out of which 2,707 km are operated by TRL (former TRC) and 970 km by Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA). The transport system also includes maritime and lake transport with major seaports of Dar es Salaam (DSM), Tanga, and Mtwara and inland water transport with ports on Lake Victoria, Tanganyika and Nyasa managed by the Tanzania Ports Authority (TPA). -

Life in Tanganyika in the Fifties

Life in Tanganyika in The Fifties Godfrey Mwakikagile 1 Copyright ( c) 2010 Godfrey Mwakikagile All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. Life in Tanganyika in the Fifties Third Edition ISBN 978-9987-16-012-9 New Africa Press Dar es Salaam Tanzania 2 3 4 Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I: Chapter One: Born in Tanganyika Chapter Two: My Early Years: Growing up in Colonial Tanganyika Chapter Three: Newspapers in Tanganyika in the Fifties: A History Linked with My Destiny as a Reporter Chapter Four: Tanganyika Before Independence 5 Part II: Narratives from the White Settler Community and Others in Colonial Tanganyika in the Fifties Appendix I: Sykes of Tanzania Remembers the Fifties Appendix II: Paramount Chief Thomas Marealle Reflects on the Fifties: An Interview Appendix III: The Fifties in Tanganyika: A Tanzanian Journalist Remembers Appendix IV: Remembering Tanganyika That Was: Recollections of a Greek Settler Appendix V: Other European Immigrants Remember Those Days in Tanganyika Appendix VI: Princess Margaret in Tanganyika 6 Acknowledgements I WISH to express my profound gratitude to all the ex- Tanganyikans who have contributed to this project. It would not have taken the shape and form it did without their participation and support. I am also indebted to others for their material which I have included in the book. Also special thanks to Jackie and Karl Wigh of Australia for sending me a package of some material from Tanganyika in the fifties, including a special booklet on Princess Margaret's visit to Tanganyika in October 1956 and other items. As an ex-Tanganyikan myself, although still a Tanzanian, I feel that there are some things which these ex-Tanganyikans and I have in common in spite of our different backgrounds. -

Working System for DAR PORT EFFICIENCY

A Quarterly Magazine of Tanzania Ports Authority ISSUE No: 02 September - December, 2018 P.O. Box 9184 Dar es Salaam | Toll free: 0800110032 / 0800110047 | Email: [email protected] | www.ports.go.tz Working System for DAR PORT EFFICIENCY @tanzaniaportshq @ tanzaniaportshq @ tanzaniaportshq @TPAHQ OUR MISSION To develop and manage ports that provide world class Maritime Services and promote excelling total logistics services in Eastern Central and Southern Africa. OUR VISION To lead the regional maritime trade and logistics services to excellence. VALUE STATEMENT A Stable Systematic Caring Organization. TANZANIA PORTS AUTHORITY Bandari Tower - One Stop Centre 1/2 Sokoine Drive P.O. Box 9184, 11105 Dar es Salaam - Tanzania Tel: +255 22-2115559/2117816 Fax: +255 22 2117816 Toll Free Number: 0800-110032/110047 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.ports.go.tz CONTENTS OUR Tsh. 9 bil for construction of New Board Vision spelt out NEW VESSEL PRIORITIES 06 new passenger vessel 18 TPA Five Year record Over 500M/- spent on Social PERFORMANCE impressive 07 SOCIETY schemes 19 OUR MTWARA Bulk Liquid Cargo TPA Photos 09 GALLERY 20 TPA remits 254.2M/- DAR, Tanzania Ports hubs regional DIVIDEND to Government 11 MTWARA economy 22 ISO TPA for ISO quality Ample opportunities ahead 9001: 2015 management certification 12 TANGA (EACOP) at Tanga Port 24 Dar port readies for Courtesy to Chinese Naval LARGER HEALTH Panamax vessels Hospital Pays off 13 VESSELS 25 TPA meets local, transit MARKETING clientele 15 PROGRESS TPA soldiers on 26 LAKE Mwanza - Port Bell Route VICTORIA Revamped 17 @tanzaniaportshq @ tanzaniaportshq @ tanzaniaportshq @TPAHQ Editor’s Message stakeholders, customers and you our readers.