The Development of Leadership Competencies for Children and Youth for Implementation in Pathfinder Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development, Acceptance, and Concerns Surrounding App-Based Services to Overcome the COVID-19 Outbreak in South Korea: Web-Based Survey Study

JMIR MEDICAL INFORMATICS Park et al Original Paper Development, Acceptance, and Concerns Surrounding App-Based Services to Overcome the COVID-19 Outbreak in South Korea: Web-Based Survey Study Jihwan Park1, PhD; Jinhyun Han2, BA; Yerin Kim3; Mi Jung Rho2, PhD 1School of Software Convergence, College of Software Convergence, Dankook University, Yongin-si, Republic of Korea 2Department of Urology, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea 3Department of Korean Language and Literature, The Anyang University of Korea, Anyang-si, Republic of Korea Corresponding Author: Mi Jung Rho, PhD Department of Urology, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital College of Medicine The Catholic University of Korea 222 Banpo-daero, Seocho-Gu Seoul, 06591 Republic of Korea Phone: 82 222585905 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Since the COVID-19 outbreak, South Korea has been engaged in various efforts to overcome the pandemic. One of them is to provide app-based COVID-19±related services to the public. As the pandemic continues, a need for various apps has emerged, including COVID-19 apps that can support activities aimed at overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic. Objective: We aimed to determine which apps were considered the most necessary according to users and evaluate the current status of the development of COVID-19±related apps in South Korea. We also aimed to determine users'acceptance and concerns related to using apps to support activities to combat COVID-19. Methods: We collected data from 1148 users from a web-based survey conducted between November 11 and December 6, 2020. -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

State of the Marine Environment Report for the NOWPAP Region (SOMER 2)

State of the Marine Environment Report for the NOWPAP region (SOMER 2) 2014 1 State of Marine Environment Report for the NOWPAP region List of Acronyms CEARAC Special Monitoring and Coastal Environmental Assessment Regional Activity Centre COD Chemical Oxygen Demand DDTs Dichloro-Diphenyl-Trichloroethane DIN, DIP Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen, Dissolved Inorganic Phosphorus DO Dissolved Oxygen DSP Diarethic Shellfish Poison EANET Acid Deposition Monitoring Network in East Asia EEZ Exclusive Economical Zone FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FPM Focal Points Meeting GDP Gross Domestic Product GIWA Global International Waters Assessment HAB Harmful Algal Bloom HCHs Hexachlorcyclohexane compounds HELCOM Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission HNS Hazardous Noxious Substances ICARM Integrated Coastal and River Management IGM Intergovernmental Meeting IMO International Maritime Organization 2 JMA Japan Meteorological Agency LBS Land Based Sources LOICZ Land-Ocean Interaction in the Coastal Zone MAP Mediterranean Action Plan MERRAC Marine Environmental Emergency Preparedness and Response Regional Activity Center MIS Marine invasive species MTS MAP Technical Report Series NGOs Nongovernmental Organizations NIES National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan NOWPAP Northwest Pacific Action Plan OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic PAHs Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons PCBs PolyChloro-Biphenyles PCDD/PCDF Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins/ Polychlorinated dibenzofurans -

Midwest University Wdc Campus 2021-2022 Catalog

2 MIDWEST UNIVERSITY WDC CAMPUS 2021-2022 CATALOG Founded in 1986 5103-A Backlick Rd. #24 Annandale, VA 22003 Office: (571) 730-4750, (703) 626-8712 Fax: (571) 730-4751 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Office Hours: Monday-Friday 8:30 a.m.- 4:30 p.m. Central Standard Time Homepage: www.midwest.edu E-mail: [email protected] Midwest University 2020-2021 This catalog is designed to help students and parents to understand the opportunities and challenges at Midwest University today. It was prepared and updated with the best information available as of current catalog printing. All information, including statements of tuition and fees, course offerings, admission and graduation requirements, is subject to change without notice or obligation. 1 Midwest University 2020-2021 Midwest University Campus - Wentzville, Missouri 2 Midwest University 2020-2021 Dedication ceremony for Dr. Jin Kyung Chung Memorial Building 2004 In loving memory of Dr. Marlin Nelson 3 Midwest University 2020-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................... 4 J-1 Exchange Visitor Program ..................................... 29 Message from the Chair of Board of Trustees ............... 5 Nondiscriminatory Policy ............................................ 30 Message from the Founder / President........................... 6 Policy for Disabled Students ....................................... 30 General Information ..................................... 7 Academic Policies and Procedures ............ 31 General Information...................................................... -

Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Published by the National Library of Korea

2014 Editorial Board Members: Copy Editors: Erica S. Chang Philip Melzer Mikyung Kang Nancy Sack Miree Ku Yunah Sung Hyokyoung Yi Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Published by the National Library of Korea The National Library of Korea 201, Banpo-daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul, Korea, 137-702 Tel: 82-2-590-6325 Fax: 82-2-590-6329 www.nl.go.kr © 2014 Committee on Korean Materials, CEAL retains copyright for all written materials that are original with this volume. ISBN 979-11-5687-075-3 93020 Handbook for Korean Studies Librarianship Outside of Korea Table of Contents Foreword Ellen Hammond ······················· 1 Preface Miree Ku ································ 3 Chapter 1. Introduction Yunah Sung ···························· 5 Chapter 2. Acquisitions and Collection Development 2.1. Introduction Mikyung Kang·························· 7 2.2. Collection Development Hana Kim ······························· 9 2.2.1 Korean Studies ······································································· 9 2.2.2 Introduction: Area Studies and Korean Studies ································· 9 2.2.3 East Asian Collections in North America: the Historical Overview ········ 10 2.2.4 Collection Development and Management ···································· 11 2.2.4.1 Collection Development Policy ··········································· 12 2.2.4.2 Developing Collections ···················································· 13 2.2.4.3 Selection Criteria ···························································· 13 2.2.4.4 -

One Less Nuclear Power Plant

One Less Nuclear Power Plant Nuclear Power One Less One Less Nuclear Power Plant energy.seoul.go.kr Climate and Environment Headquarters evn.seoul.go.kr Seoul Energy Dream Center www.seouledc.or.kr One Less Environmental Dispute Committee edc.seoul.go.kr Nuclear Since the Fukushima nuclear accident, more people leaned Seoul Environmental Impact Assessment towards phasing out of nuclear power plants. In addition, themassive blackout throughout the whole nation led to the initiation of the eims.seoul.go.kr ‘One Less Nuclear Power Plant’ in May 2012 with the aim to substitute Power Plant the amount of power produced by one nuclear power plant with new Seoul Air Quality Information and renewable energy production and energy conservation and to cleanair.seoul.go.kr proactively respond to the energy crisis and the climate change. A Hopeful Message of Seoul’s Energy Policy The initial objective was to reduce 2 million TOE of energy Seoul Air Quality Information by December 2014, but thanks to the willingness of the Seoul ecomileage.seoul.go.kr Metropolitan City paired with the participation of the citizens and corporations, we were able to meet our goal 6 months in advance. Asbestos Management Information System asbestos.seoul.go.kr Seoul No-driving Day no-driving.seoul.go.kr Seoul Flea Market fleamarket.seoul.go.kr Resource Recovery Facility rrf.seoul.go.kr “Citizens are Energy” Publisher Mayor of Seoul Metropolitan Government Produced by Climate and Environment Headquarters, One Less Nuclear Power Plant Citizens Commission · Execution Committee Issued by Seoul Metropolitan Government energy.seoul.go.kr Issued November, 2014 Issuer Environmental Policy Division (Tel. -

Korean Council for University Education Bringing Change and Innovation to Universities 2015-2016 Contents

RM 2015-10-667 Korean Council for University Education bringing change and innovation to universities 2015-2016 Contents Part 1 Introduction to the Korean Council for University Education (KCUE) KCUE’s function and role ● Overview of KCUE ● Key Projects KCUE’s key projects ● University Admission System ● Institutional Accreditation ● Information Disclosure of Higher Education Institution Part 2 Overview of Higher Education in Korea Part 3 List of Member Universities Part 4 KCUE’s MOUs Part I Introduction to the Korean Council for University Education (KCUE) KCUE’s function and role Overview of KCUE ■ The Korean Council for University Education (KCUE), as a consultation body and an intermediary between the government and the universities, seeks to promote sound development of universities through autonomous rule and mutual cooperation in the universities to bring together and represent the collective voices of universities to the government and the National Assembly; and to conduct projects commissioned by the government. That is, through the process of building consensus and cooperation between universities, the KCUE helps Korean universities make progress in their pursuit of achieving greater autonomy and fulfilling their responsibilities in response to the expectations from the government and the public. ■ The KCUE serves as a buffer between universities and the government by faithfully representing the universities’ needs and guiding the right direction for future policy development. In addition, the KCUE conducts projects commissioned by the government and supports universities. Furthermore, the KCUE submits opinions to the National Assembly in regard to enactment and amendment of laws related to university education. The KCUE periodically receives parliamentary audits of overall projects and its implementation to ensure its role as a public institution. -

Ajou-2017-Book-Of-Abstracts.Pdf

ARTIS International Symposium 105 Jonghap Hall Ajou University Suwon, South Korea 12–14 January 2017 Ajou Center for Translation and Interpreting Studies (ACTIS) Advancing Research in Translation and Intercultural Studies (ARTIS) 1 2 ARTIS@Ajou2017 Translation and Knowledge: From Knowledge Production to Collective Intelligence on the Web Book of Abstracts 105 JONGHAP HALL Ajou University Suwon, South Korea 12-14 January 2017 3 ARTIS@AJOU2017 Contact [email protected] 4 Program 5 ARTIS International Symposium Translation and Knowledge: From Knowledge Production to Collective Intelligence on the Web 12-14 January 2017 105 Jonghap Hall, Ajou University, South Korea Ajou Center for Translation and Interpreting Studies (ACTIS) Program 12 January Day one 9:00-9:30 Registration and coffee 9:30-9:45 Opening session Chair: Ji-Hae Kang (Ajou University, South Korea) Welcoming speech Man-Ghyu Pak (Dean, College of Humanities, Ajou University, South Korea) Welcome and introduction Ji-Hae Kang (Director, Ajou Center for Translation and Interpreting Studies, South Korea) 9:45-11:00 Lecture 1 Chair: Sungeun Cho (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea) Investigating Translation and Knowledge Production at the Digital Crossroads Luis Pérez-González (University of Manchester, UK) 11:00-11:30 Tea and coffee 11:30-13:00 Panel 1 Chair: Won-Jun Nam (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea) Technology and the Role of Translation in the Knowledge Production and Dissemination, What Next? Silhee Jin (Chung-Ang University, South Korea) -

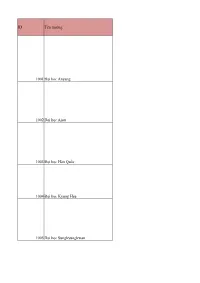

ID Tên Trường 1001 Đại Học Anyang 1002 Đại Học Ajou 1003 Đại Học

ID Tên trường 1001 Đại học Anyang 1002 Đại học Ajou 1003 Đại học Hàn Quốc 1004 Đại học Kyung Hee 1005 Đại học Sungkyungkwan 1006 Đại học Yonsei 1007 Đại học Nghệ thuật Baekseok 1008 Đại học Chosun 1009 Đại học KHOA HỌC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ 1010 Đại học Hanyang 1011 Đại học Inha. 1012 Đại học Sogang 1013 Đại học Chung-ang 1014 Đại học Hallym 1015 Đại học nữ Sookmyung Học viện khoa học và công nghệ Hàn 1016 Quốc 1017 Đại học Kwangwoon 1018 ĐH nữ Ewha 1019 Đại học Soongsil 1020 Đại học Konkuk 1021 Đại học Dongguk 1022 Đại học Kookmin 1023 Đại học Dankook 1024 Đại học Quốc gia Jeju 1025 Đại học Quốc gia Chonnam 1026 Cao đẳng Cheonan Yonam 1027 ĐH Quốc gia Chungbuk 1028 Đại học Nghệ thuật Daegu 1029 Đh Daegu Haany 1030 Đại học Daejin 1031 Đại học Daejeon 1032 Đại học nữ Dongduk 1033 Đại học Dongseo 1034 Đh Dongshin 1035 Đh nữ Duksung 1036 Đại học Chungwoon 1037 Đại học Dong-A 1038 Đại học Dong Eui 1039 Đại học Eulji 1040 Đại học Gachon 1041 Đại học Quốc gia Gangneung-Wonju 1042 Đại học Geumgang 1043 Đại học Giáo dục Quốc gia Gongju 1044 Đại học Gukje Cyber 1045 Viện Khoa học và Công nghệ Gwangju 1046 Đại học Giáo dục Quốc gia Gwangju 1047 Đại học Gyeongju Đại học Quốc gia Khoa học và Công 1048 nghệ Gyeongnam 1049 Đại học Quốc gia Gyeongsang 1050 Đại học Cheju Halla 1051 Đại học Quốc gia Hanbat 1052 Đại học Quốc tế Handong 1053 Đại học Không gian vũ trụ Hàn Quốc 1054 Đại học Quốc gia Hankyong 1055 Đại học Hannam 1056 Đại học Hansei 1057 Đại học Hanshin 1058 Đại học Hansung 1059 Đại học Hongik 1060 Đại họcGiáo dục Quốc gia Jeonju 1061 Đại học Jeonju -

I:\2016==GR Sharma Formating Jo

I J A B E R, Vol. 14, No. 5, (2016): 2893-2911 THE EFFECTS OF U-CITY SECURITY SERVICE ON CRIME RATES Hyewon Kim*, Kabsung Kim** and Joohyun Lee*** Abstract: The national economy of South Korea has grown exponentially after 1960s, resulting in the urbanization rate to soar 39.1% in 1960 to 91.5% in 2013. However, unlike the rapid quantitative growth, a slow trend in qualitative growth of cities has resulted in a number of urban problems, especially in crime. A number of recent studies have focused on the factors influencing crime rates, the spatial effects of crime, as well as cities operating Ubiquitous Security service for the purpose of crime prevention. This study aims to address the effects of Ubiquitous city (U-city) on crime rates within the metropolitan area of Seoul. The study first analyzes the geographical distribution of crime rates and then identifies the existence of spatial autocorrelation of crime rates within Seoul. Finally, the study determines whether the execution of U-Security service affects crime rates and other urban characteristics that influence crime rates. These effects are determined by applying spatial regression models, which can control the spatial effects and other effects of other urban characteristics on crime rates. The results of this analysis show that U-City security service does not have a statistically significant effect on crime rates. The study can be used to support the application of U-City security service to regions with high crime rates, and to address the needs of future studies that aim to compare crime rates before and after the application of U-City security service. -

Impact of Isoprene and HONO Chemistry on Ozone and OVOC Formation in a Semirural South Korean Forest

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 4357–4371, 2015 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/15/4357/2015/ doi:10.5194/acp-15-4357-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Impact of isoprene and HONO chemistry on ozone and OVOC formation in a semirural South Korean forest S. Kim1, S.-Y. Kim2, M. Lee3, H. Shim3, G. M. Wolfe4,5, A. B. Guenther6, A. He1, Y. Hong2, and J. Han2,* 1Department of Earth System Science, School of Physical Sciences, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA 2National Institute Environmental Research, Incheon, South Korea 3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Korean University, Seoul, South Korea 4Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA 5Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA 6Atmospheric Sciences and Global Change Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland WA, USA *now at: Department of Environmental & Energy Engineering, Anyang University, Anyang, South Korea Correspondence to: S. Kim ([email protected]) Received: 1 May 2014 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 24 June 2014 Revised: 27 March 2015 – Accepted: 27 March 2015 – Published: 29 April 2015 Abstract. Rapid urbanization and economic development atic differences in HOx distributions, especially OH levels in East Asia in past decades has led to photochemical air (up to 2.5 times), and (2) radical destruction (HO2 C HO2 or pollution problems such as excess photochemical ozone HO2 C RO2/ could be more efficient than radical recycling and aerosol formation. Asian megacities such as Seoul, (RO2 C NO), especially in the afternoon. Implications of the Tokyo, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing are surrounded by uncertainties in radical chemistry are discussed with respect densely forested areas, and recent research has consistently to ozone–VOC–NOx sensitivity and VOC oxidation product demonstrated the importance of biogenic volatile organic formation rates.