Thesis Final Electronic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Spring 2013 8:00 P.M

Friday, May 17 Grant from the Southeastern Minnesota Spring 2013 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Arts Council. Carleton Symphony Band Concert This activity is made possible by the voters of Ronald Rodman, director Sunday, April 7 Minnesota through a grant from the South- 3:00 p.m. Concert Hall The Symphony Band wraps up the aca- eastern Minnesota Arts Council thanks to a Faculty Recital demic year with a concert celebrating the legislative appropriation from the arts & cultural “Exploring Organ Music: A Survey of graduating seniors. Christophe Dethier heritage fund. Manualiter Organ Music: Program III” ‘13 will be featured as clarinet soloist Lawrence Archbold, organ performing Weber’s Concertino. Other Thursday, May 30 pieces on the program include Mendels- 12:10 p.m. Concert Hall This concert is the third in a third series sohn’s Fingal’s Cave Overture, Tichelli’s Student Chamber Recital I of “Exploring Organ Music” recitals Blue Shades, Four Scottish Dances by Nicola Melville, coordinator presented by Lawrence Archbold, the Enid Malcolm Arnold, and music from the and Henry Woodward College Organist. film, The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey Friday, May 31 “A Survey of Manualiter Organ Music: by Howard Shore. 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Program III” features an all-French pro- Carleton Orchestra Concert gram with music by ten composers from Timothy Semanik, director three centuries, c.1650 to c.1950, includ- Saturday, May 18 ing Couperin, Franck, and Messiaen. 8:00 p.m. Chapel Guest Artist Concert The Carleton Orchestra’s Spring Concert will include Johannes Brahms’ Second Friday, April 19 The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Symphony as well as performances by this 8:00 p.m. -

Song/Casting: Combining Podcasts and Songs to Create a Hybrid Medium

Nate Sahr 1 Song/Casting: Combining Podcasts and Songs to Create a Hybrid Medium A Thesis Presented to the Honors Tutorial College, Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Media Arts & Studies By Nate Sahr May 2021 Nate Sahr 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction – What is a Songcast? 4 The Hypothetical Songcast: Preliminary Research & Codification 9 Storytelling in Podcasts 10 Storytelling in Songs 12 Parasocial Relationships 14 Music 16 The Actual Songcast: Creative Process 17 Evaluating my Songcast 30 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 34 Nate Sahr 3 Abstract In my creative project and associated paper, I explore a hybrid medium, songcasting, that combines the most compelling elements of podcasts with the most compelling elements of songs. For the creation of this specific songcast, I interviewed 7 talented storytellers to capture audio recordings of them telling stories. From these, I chose a story about a Minnesotan teenager and his sister exploring Australia in 1979, and I built my songcast around it. This story explores coming of age, what it means to live in the modern world, cross-cultural relations, and more. The music and narration are carefully arranged and fused together to provide an immersive listening experience. While this songcast highlights the medium’s strengths, it is only one example of the many possibilities of songcasting. By synthesizing music, an emphasis on parasocial relationships, and the storytelling modes of both songs and podcasts, songcasts stand apart as unique audio format. Nate Sahr 4 Introduction – What is a Songcast? Imagine a spectrum: on one side of the spectrum is the color blue, on the other side is the color yellow. -

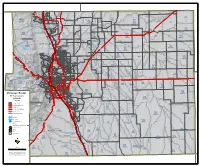

Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment

MonumentMonument CreekCreek WatershedWatershed LandscapeLandscape AssessmentAssessment a Legacy Resource Management Program Project Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment prepared for: United States Air Force Academy 8120 Edgerton Dr Ste 40 Air Force Academy CO 80840-2400 prepared by: John Armstrong and Joe Stevens Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University, College of Natural Resources Fort Collins CO 80523 31 January 2002 Copyright 2002 Colorado Natural Heritage Program Cover photo: Panorama of Pikes Peak and the Rampart Range (the western boundary of the Monument Creek Watershed) from Palmer Park. Photograph by J. Armstrong. Funding provided by the Legacy Resource Management Program, administered by the US Army Corps of Engineers. table of contents list of figures ................................................................................................3 list of tables ..................................................................................................3 list of maps ..................................................................................................3 list of photographs .....................................................................................4 acknowledgements...........................................................................................5 introduction .......................................................................................................7 project history .............................................................................................7 -

Guy Mendilow Ensemble TFFK

FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM PERFORMED BY THE GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE COMPLETE PRESENTER’S KIT (CLIck ON A HEADING PAGE TO NAVIGATE IT) The Show …………………………………………………………………….…...…....p. 1 NOW TOURING: TALES FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM Presenters’ Testimony: Audience Impact….....…………………….……...... p. 2 Media Recognition..………..………………………….……………………….…….p. 3 Audio & Video Samples……………………….……………………………………..p. 4 About the Guy Mendilow Ensemble………………….…….………………..….p. 5 Cast Bios………………….………….………………………………….……………....p. 6 Select Performance Credits……………..……………………………………..…..p. 8 Discography, Radio, Television & Film Credits….…………………….….....p. 9 ADDITIONAL OFFERINGS University Lecture Demos…………….………….……………………………….p.10 Residences & Workshops: 13 yrs — Adult……………………………………p. 11 Residences & Workshops: Children……………….…………………………..p.11 Family Performances……………………………………………………………....p.12 Process: Springboarding from Tradition into Modern Imagination ….p. 13 Booking/Management: Guy Mendilow : Tel. +1.857-222-0235 | Fax 617-524-1463 | [email protected] www.guymendilow.com INDEX FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM PERFORMED BY THE GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE THE SHOW Embark on a musical trek to kingdoms long forgotten and bustling towns now vanished. Follow the stories of vagabond queens, pauper poets and lovers lost to the sea, all set to spellbinding arrangements of old Sephardi songs worthy of symphonic film scores. Wrap these tales up with lush soulful harmonies evoking Flamenco’s gutsiness and the longings of Fado, all combined with heart-pounding percussion, masterful narration -

The Embassy Theatre Gets

PROJECT BALLET ACADEMIC CONSERVATORY things to do World class. Nationwide impact. Right here in Fort Wayne. pg12-13 285 in the area CALENDARS START ON PAGE 10 Jan. 24-30, 2019 FREE WHAT THERE IS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND THE EMBASSY TONY AWARD- THEATRE GETS WINNING KINKY BOOTS STEPS INTO TOWN. KINKY PAGES 8-9 ALSO INSIDE: LOCAL MUSIC COVERAGE INCLUDES STRANGE WATERS, KEVIN HAMBRICK, AND ALICIA PYLE whatzup.com Inside This Week Volume 23, Number 26 4The Harlem TRADE UP Globetrotters in 2019 5 Make Your Old Gear New Jefferson We will help you sell your Starship gear on consignment or trade it in on the spot for in-store credit 6Kinky Boots 8New Clyde executive director 12Project Ballet Columns & Reviews Calendars Spins ⁄ 9 Picks ⁄ 16 Music/On the Road ⁄ 10-11 Visit the Gear Exchange today! Kevin Hambrick, Stephen Pearcy Bizet’s Carmen with The Fort Wayne Philharmonic and Chorus, Road Trips ⁄ 11 Backtracks ⁄ 9 Tuck Everlasting with Fire & Light Live Music & Comedy ⁄ 15-18 The Frost, Frost Music (1969) Productions Stage & Dance ⁄ 21 Road Notes ⁄ 10-11 Reel Views ⁄ 19 The Who answer yes to tour, new Glass: Shyamalan flips comic book Things To Do ⁄ 22 album formula Art & Exhibits ⁄ 23 Out and About ⁄ 14 Screen Time ⁄ 20 Hit the tropics with local surf rock Glass hits ceiling; The Upside still up 5501 US Hwy 30 W quartet Fort Wayne, IN 46818 JANUARY 24-30, 2019 WHATZUP 3 How to reach us Family fun from basketball court jesters Whatzup LLC 5501 U.S. Highway 30 West Fort Wayne, IN 46818 Globetrotters Phone: (260) 407-3198 Fax: (260) 469-1027 dribble their way [email protected] whatzup.com to the Coliseum facebook.com/whatzupftwayne instagram.com/whatzupftwayne BY HEATHER HERRON twitter.com/whatzupftwayne WHATZUP FEATURES WRITER Publisher It’s a life Chandler “Bulldog” Mack Gerson Rosenbloom could only dream of when growing up in Huntsville, Ala. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Park County, Colorado, Historic Cemeteries B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Historic Cemetery Development in Park County, Colorado, 1859-1965 C. Form Prepared by name/title R. Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons organization Front Range Research Associates, Inc. date October 2016 street & number 3635 W. 46th Ave. email [email protected] telephone 303-477-7597 city or town Denver state Colorado zip code 80211 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements -

Colorado 1 (! 1 27 Y S.P

# # # # # # # # # ######## # # ## # # # ## # # # # # 1 2 3 4 5 # 6 7 8 9 1011121314151617 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 ) " 8 Muddy !a Ik ") 24 6 ") (!KÂ ) )¬ (! LARAMIE" KIMBALL GARDEN 1 ") I¸ 6 Medicine Bow !` Lodg Centennial 4 ep National Federal ole (! 9 Lake McConaughy CARBON Forest I§ Kimball 9 CHEYENNE 11 C 12 1 Potter CURT GOWDY reek Bushnell (! 11 ") 15 ") ") Riverside (! LARAMIE ! ") Ik ( ") (! ) " Colorado 1 8 (! 1 27 Y S.P. ") Pine !a 2 Ij Cree Medicine Bow 2 KÂ 6 .R. 3 12 2 7 9 ) Flaming Gorge R ") " National 34 .P. (! Burns Bluffs k U ") 10 5 National SWEETWATER Encampment (! 7 KEITH 40 Forest (! Red Buttes (! 4 Egbert ") 8 Sidney 10 Lodgepole Recreation Area 796 (! DEUEL ") ) " ") 2 ! 6 ") 3 ( Albany ") 9 2 A (! 6 9 ) River 27 6 Ik !a " 1 2 3 6 3 CHEYENNE ") Brule K ") on ") G 4 10 Big Springs Jct. 9 lli ") ) Ik " ") 3 Chappell 2 14 (! (! 17 4 ") Vermi S Woods Landing ") !a N (! Ik ) ! 8 15 8 " ") ) ( " !a # ALBANY 3 3 ^! 5 7 2 3 ") ( Big Springs ") ") (! 4 3 (! 11 6 2 ek ") 6 WYOMING MI Dixon Medicine Bow 4 Carpenter Barton ") (! (! 6 RA I« 10 ) Baggs Tie Siding " Cre Savery (! ! (! National ") ( 6 O 7 9 B (! 4 Forest 8 9 5 4 5 Flaming UTAH 2 5 15 9 A Dutch John Mountain ") Y I¸11 Gorge (! 4 NEBRASKA (! (! Powder K Res. ^ Home tonwo 2 ^ NE t o o ! C d ! ell h Little En (! WYOMING 3 W p ! 7 as S Tala Sh (! W Slater cam ^ ") Ovid 4 ! ! mant Snake River pm ^ ^ 3 ! es Cr (! ! ! ^ Li ! Gr Mi en ^ ^ ^ ttle eek 8 ! ^JULESBURG een Creek k Powder Wash ddle t ! Hereford (! ! 8 e NORTHGATE 4 ( Peetz ! ! Willo ork K R Virginia Jumbo Lake Sedgwick ! ! # T( ") Cre F ing (! 1 ek Y 7 RA ^ Cre CANYON ek Lara (! Dale B I§ w Big Creek o k F e 2 9 8 Cre 9 Cr x DAGGETT o Fo m Lakes e 7 C T(R B r NATURE TRAIL ") A ee u So k i e e lde d 7 r lomon e k a I« 1 0 Cr mil h k k r 17 t r r 293 PERKINS River Creek u e 9 River Pawnee v 1 e o e ") Carr ree r Rockport Stuc Poud 49 7 r® Dry S Ri C National 22 SENTINAL La HAMILTON RESERVOIR/ (! (! k 6 NE e A Gr e Halligan Res. -

Drainage Basins D R R a F A

EEllbbeerrtt CCoouunnttyy Coommeerrccee Rdd d d R R h h Douglas County a Douglas County a m m rr a a d d D R D R R R t t Fremont C k Fremont P C k r P r w e w W rr e e h a W e a av h E h avy e h y e E s O d d s st rs Oa DD d r k r o d t r a n e r o n relllla ee k Dr a K r n Fort e L K n Fort L B kk e Carpenter n C B Carpenter R n C b R Bald u L b ee u Bald L r S v Plum r v ee Plum l k h i o e k h r i o e l r RAMAH D g rr l l D g l n a l n a d T G G T i h r G d G ok St h r CC o E ro St r B ok i Bro o r t i E t n d d Sundance Mountain d d e n r E p e r E Creek kk p R oo W g E Creek H R g E W ll v Mountain w v H w R u R R M ountain R u r Creek r Creek W EE t W r cc o H i r h t o H i e e a Antelope h n D a d n e i D e p n a d Antelope o n p o e g n a n r r g WW dd e e d g o e e d g T o H R n PLPL0400 e e T l n 8285 l e T H R T g PLPL0400 D g F m PLPL020 0 F West D u e D u m PLPL0200 PLP0600 D e v a West r a r d v t PLP0600 d t m l r a i l r h k S l k l i h rr a m S i l r l i dd g c n d r R w c r amah n E R Rd g i r a E Ramah w o T DD u i a PALMER LAKE o D T amah Rd D E R u G R d k ah R r G d RR am h * R k e E A r n d R o e n A * h oo S S o a n c e a d e n r c d cc r Creek C m r r W ee D C W m D aa s o e Creek R C l s r Ca o e o l t S a h r R t e rr b h r r d e d o b S e p dr D d e p ra D e R M l a l oss a e L R M Rock l D a l oss Rd mm L Dr e Rock Rd u DD r r l s e m a r l s lm t a u l B s r o B aa l t t s r o l t h M lh r P l r M F C S P e e e l e C S g gg a e F l e g a i l n a W Ramah Rd i l n a Rd t o A W Ramah o p t A d r C nn p d r C -

Cogjm.Rmo-604.Pdf (1.625Mb)

RMO- 6~~lV 3m!c -o UNITED STATES DEPART~illNT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INVESTIGATIONS OF DO~STIC RADIOACTIVE RAW MATERIALS, BERYLLIUM, AND OTHER TRACE ELE~NTS (J PREPARED FOR U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION MONTHLY REPORT--NOVEMBER 1951 TRACE ELEMENTS OFFICE C] Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any.oftheir employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. REPRODUCED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY -2- CJ .3 Page SUIDinary .......................................................................... o .......... o o .................. " ~ .......... .. 7 Reconnaissance investigations, domestic .......................................................... .. 9 Property examinations .................................................................................. .. 9 Copper-uranium deposits in sandstones .................................................... .. 9 Relation -

APPENDIX a APPENDIX a Tiliber SALE Sumllary

APPENDIX A APPENDIX A TIliBER SALE SuMllARY Area r.ocarmn -“anagemenr Area Treatmentl Esrlmated Probable Harvest -RIS I.ocatmn Area Volume “ethods by -Towashw & Range* (Acres) m LlpiBF Forest Type 1984 leadvllle 28 30 57 02 lodgepole pine 100210 clearcut T9S, R80W 1984 Leadvllle 2B 30 86 03 Lodgepole pne 100210 clearcut T8S. mow 1984 Leadvllle 70 50 143 03 bdgepole pule 100203 clearcur; spruce,fr ms, R80W shelterwood 1984 Leadvllle lhstrxt-vlde 80 2.29 08 All species. approprrare for nanagement Area.*=C 1984 Sahda 4B 320 457 16 Spruce,flr group 101001; 101002 selectmn T14S, R80W 1984 Sallda 40 200 114 0.4 Douglas-*rr thmnmg; 102311 lodgepole pine and T48N, WE aspen. clearcur 1984 SalIda 5B 15 29 0 1 Lodgepole pm 102211 clearcur T49N, R7E 1984 Salzda 5B 30 86 0.3 Aspen: clearcut 1027.06 public fuelwood T49N, WE 1984 Sahd.9 40 25 86 0.3 Aspen clearcur 101301 public fuelwood T13S, R77W 1984 Sahda District-wide 320 200 0.7 All species approprrate for nanagement Area 1984 San Carlas ,A 318 loo0 3.5 Spruce,fx. clearcut; 103510 Douglas-fir: two-step T24S, R69W sheltewood 1984 San carkss rhstrzct-wrde 420 257 0.9 All Epecles appropriate for Management Area 1984 Pxkes Peak WE 314 143 0.3 Ponderosa pine and 115302. 113303 Douglas-cr. Two-step TI1S. R68W shelterwad; spruce/ fm and aspen clearcut 1984 PlkS Peak 7A 476 286 10 Douglas-fm and 117101, 117102, ponderosa pme two- 117401, 11,402 step shelterwood, T11 s; 12s. wow aspen. clearcur *All Townshq and Range ~~rar~ons refer to the New “exzco and Sxcth Prmcxpal “enduas, ““Ifed States survey “See Chapter III, Management Area Preserqrmns for harvest methods by specks A-l TIMBER SALE SuMEwlY Area hcatlo” -Managemn Area Treatment Estmated Probable Harverr Hlscal -RI8 locatloo Area Yolme Methods by Year: District Sale Name -Township 6 Ranae (Acres) gcJ MMBF Forest Type 1984 Pikes Peak .Jobos Gulch 1OR 450 286 I.0 Poaderosa pm.e 116701, 116002 two-step shelterwood T118, R69” 1984 Pikes Peak Quaker RLdgs 28 250 143 0.5 Ponderoaa pme TWO- 116601. -

Colorado Bighorn Sheep Management Plan 2009−2019

1 2 Special Report Number 81 3 COLORADO 4 BIGHORN SHEEP MANAGEMENT PLAN 5 2009−2019 6 J. L. George, R. Kahn, M. W. Miller, B. Watkins 7 February 2009 COLORADO DIVISION OF WILDLIFE 8 TERRESTRIAL RESOURCES 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 SPECIAL REPORT NUMBER 81 9 Special Report Cover #81.indd 1 6/24/09 12:21 PM COLORADO BIGHORN SHEEP MANAGEMENT PLAN 2009−2019 Editors1 J. L. George, R. Kahn, M. W. Miller, & B. Watkins Contributors1 C. R. Anderson, Jr., J. Apker, J. Broderick, R. Davies, B. Diamond, J. L. George, S. Huwer, R. Kahn, K. Logan, M. W. Miller, S. Wait, B. Watkins, L. L. Wolfe Special Report No. 81 February 2009 Colorado Division of Wildlife 1 Editors and contributors listed alphabetically to denote equivalent contributions to this effort. Thanks to M. Alldredge, B. Andree, E. Bergman, C. Bishop, D. Larkin, J. Mumma, D. Prenzlow, D. Walsh, M. Woolever, the Rocky Mountain Bighorn Society, the Colorado Woolgrowers Association, the US Forest Service, and many others for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this management plan. DOW-R-S-81-09 ISSN 0084-8875 STATE OF COLORADO: Bill Ritter, Jr., Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES: Harris D. Sherman, Executive Director DIVISION OF WILDLIFE: Thomas E. Remington, Director WILDLIFE COMMISSION: Brad Coors, Chair, Denver; Tim Glenn, Vice Chair, Salida; Dennis Buechler, Secretary, Centennial; Members, Jeffrey A. Crawford; Dorothea Farris; Roy McAnally; John Singletary; Mark Smith; Robert Streeter; Ex Officio Members, Harris Sherman and John Stulp Layout & production by Sandy Cochran FOREWORD The Colorado Bighorn Sheep Management Plan is the culmination of months of work by Division of Wildlife biologists, managers and staff personnel.