Air Force Academy Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Over Boston 1992 Second Air Division Association President's Message Eighth Air Force by Richard M

Over Boston 1992 Second Air Division Association President's Message Eighth Air Force by Richard M. Kennedy 1992!!! This year marks the 50th anniversary of the HONORARY PRESIDENT JORDAN UTTAL founding of the 8th Army Air Force. Shortly after the 7824 Meadow Park Drive, Apt. 101, Dallas, TX 75230 initial cadre of personnel was formed the 8th was deployed to the United Kingdom, where they prepared to take part OFFICERS President RICHARD M. KENNEDY in what proved to be a series of important campaigns 8051 Goshen Road, Malvern, PA 19355 leading to the demise of Nazi Germany. 1992 will also Executive Vice President JOHN B. CONRAD 2981 Four Pines #1, Lexington, KY 40502 register the assembly of the 2nd Air Division Association in Vice President Las Vegas to celebrate the Association's 45th Reunion. Membership EVELYN COHEN Apt. 06-410 Delaire Landing Road Two highly significant events. Philadelphia, PA 19114 1992 also records a period of 47 years since the end of Vice President Journal WILLIAM G. ROBERTIE World War II. Can we, with any degree of accuracy, begin to visualize the vast amount of P.O. Box 627, Ipswich, MA 01938 records that any one of us may have accumulated? Treasurer DEAN MOYER 2nd ADA memorabilia and 549 East Main St., Evans City, PA 16033 It has been recently brought to my attention that many of our members continue to raise Secretary DAVID G. PATTERSON have 28 Squire Court, Alamo, CA 94507 the question of "what can I, or should I, do with precious items of memorabilia that I American Representative collected and saved over those 47 years?" The question is not only valid; it is extremely perti- Board of Governors E (BUD) KOORNDYK 5184 N. -

Graduation-Program-2021.Pdf

2021 GRADUATION COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM COMMENCEMENT 2021 GRADUATION Class of 2021 EXEMPLAR: BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES ROBINSON “ROBBIE” RISNER CLASS MOTTO: PROGRAM COMMENCEMENT 2021 GRADUATION “NO DOUBT, NO FEAR” “NOLITE DUBITARE, NOLITE TIMERE” FALCON STADIUM PROGRAM Military members are reminded that a salute will be rendered during the playing of Honors for the Graduation Speaker and the National Anthem. During the National Anthem, all citizens of the United States, should face the flag with both hands at their sides or with their hat or open hand over their heart. Military retirees may render a salute during the playing of the National Anthem. 2021 GRADUATION COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM COMMENCEMENT 2021 GRADUATION MISTRESS OF CEREMONY Cadet Francesca A. Verville, Spring Wing Command Chief OFFICIAL PARTY ARRIVAL GRADUATING CLASS MARCH-ON NATIONAL ANTHEM The United States Air Force Academy Band INVOCATION Chaplain, Colonel Julian C. Gaither, US Air Force Academy Chaplain OPENING REMARKS Lieutenant General Richard M. Clark, Superintendent, United States Air Force Academy INTRODUCTION OF GUEST SPEAKER Mr. John P. Roth, Acting Secretary of the Air Force GRADUATION ADDRESS General Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff COMMENCEMENT AWARD Cadet Matthew J. Vidican, Class President Cadet Roselen J. Rotello, Summer Cadet Wing Commander Cadet Aryemis C. Brown, Fall Cadet Wing Commander Cadet Emily K. Berexa, Spring Cadet Wing Commander PRESENTATION OF DISTINGUISHED AMERICAN AWARD Mr. Matt Carpenter, Superintendent’s Leadership Endowment Board PRESENTATION OF GRADUATES Brigadier General Linell A. Letendre, Dean of the Faculty PRESENTATION OF DIPLOMAS General Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Names of graduates are read by Colonel Arthur W. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Schools Districts Buildings and Personnel

SCHOOL DISTRICTS/BUILDINGS AND PERSONNEL ADAMS School District 27J MAILING ADDRESS (LOCATION) CITY ZIPCODE PHONE STUDENT COUNT 18551 EAST 160TH AVENUE BRIGHTON 80601 303/655-2900 DISTRICT SCHOOL DISTRICT 27J 80601-3295 19,203 LEGAL NAME: 3295 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS: 6 7 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: http://www.sd27j.org FAX# 303/655-2870 DISTRICT PERSONNEL CHRIS FIEDLER SUPERINTENDENT WILL PIERCE CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER LORI SCHIEK CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER MICHAEL CLOW CHIEF HUMAN RESOURCE OFFICER LONNIE MARTINEZ OPERATIONS MANAGER TONY JORSTAD NUTRITION SERVICES SUPERVISOR EDIE DUNBAR TRANSPORTATION SUPERVISOR JEREMY HEIDE CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER JEREMY HEIDE TELECOMMUNICATIONS COORDINATOR GREGORY PIOTRASCHKE SCHOOL BRD PRESIDENT LYNN ANN SHEATS SCHOOL BRD SECRETARY BRETT MINNE SCHOOL LIBRARY MEDIA LYNN ANN SHEATS ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT TERRY LUCERO CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER MARIA SNITILY DIRECTOR OF SPECIAL EDUCATION KERRIE MONTI PLANNING MANAGER WILL PIERCE CHILD WELFARE EDUCATION LIAISON PAUL FRANCISCO ICAP CONTACT PAUL FRANCISCO GRADUATION GUIDELINES CONTACT BRETT MINNE DIRECTOR OF STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT CHRIS FIEDLER GRADUATION GUIDELINES CONTACT CHRIS FIEDLER ICAP CONTACT CHRIS FIEDLER WORK BASED LEARNING COORDINATOR ELEMENTARY/JUNIOR SCHOOLS MAILING ADDRESS CITY ZIPCODE PHONE SCHOOL PRINCIPAL TYPE Belle Creek Charter School 9290 EAST 107TH AVENUE HENDERSON 80640 303/468-0160 K-08 JACKIE FIELDS Brantner Elementary School 7800 E. 133RD AVENUE THORNTON 80602 720/685-5050 PK-05 BRITT TRAVIS Bromley East Charter School 356 LONGSPUR -

Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment

MonumentMonument CreekCreek WatershedWatershed LandscapeLandscape AssessmentAssessment a Legacy Resource Management Program Project Monument Creek Watershed Landscape Assessment prepared for: United States Air Force Academy 8120 Edgerton Dr Ste 40 Air Force Academy CO 80840-2400 prepared by: John Armstrong and Joe Stevens Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University, College of Natural Resources Fort Collins CO 80523 31 January 2002 Copyright 2002 Colorado Natural Heritage Program Cover photo: Panorama of Pikes Peak and the Rampart Range (the western boundary of the Monument Creek Watershed) from Palmer Park. Photograph by J. Armstrong. Funding provided by the Legacy Resource Management Program, administered by the US Army Corps of Engineers. table of contents list of figures ................................................................................................3 list of tables ..................................................................................................3 list of maps ..................................................................................................3 list of photographs .....................................................................................4 acknowledgements...........................................................................................5 introduction .......................................................................................................7 project history .............................................................................................7 -

A Case Study of Air Officers Commanding

DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE LEADER DEVELOPERS: A CASE STUDY OF AIR OFFICERS COMMANDING By HANS J. LARSEN B.S., United States Air Force Academy, 1999 M.A., University of Nebraska, 2000 M.A., University of Colorado, 2012 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations 2019 ii ©2019 HANS JOSEPH LARSEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii This dissertation for Doctor of Philosophy Degree by Hans J. Larsen Has been approved for the Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations By _________________________________ Dr. Andrea Bingham, Chair _________________________________ Dr. Patricia Witkowsky _________________________________ Dr. Phillip Morris _________________________________ Dr. Joseph Wehrman _________________________________ Dr. Joseph Sanders __________________ Date iv Larsen, Hans J. (PhD, Educational Leadership, Research, and Policy) Developing Effective Leader Developers: A Case Study of Air Officers Commanding Dissertation directed by Assistant Professor Andrea Bingham This dissertation is a qualitative case study that examined how the United States Air Force Academy’s (USAFA) Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Master’s Program prepares officers to be leader developers. AOCs are sent through a one-year education and training program called the AOC Master’s Program. Interviews, document reviews, and observations were conducted with AOCs while currently at USAFA, both within the program and in command, to determine what dispositions, behaviors, and skills make for an effective leader developer and how the program prepares them for this role. Findings from the research revealed the importance of possessing the proper disposition toward development, engaging in sensemaking, modeling, and psychological safety in fulfilling the role of a leader developer. -

Curriculum Vitae

SALLY STEINDORF, Ph.D. Global Studies Department, Chair Women’s & Gender Studies, Program Director Principia College, One Maybeck Place, Elsah, IL 62028 [email protected] 618.374.5204 (o) 314.369.7129 (c) EDUCATION Syracuse University, Maxwell School, Syracuse, New York Ph.D. May 2008, Cultural Anthropology Dissertation Title: Walking Against the Wind: Negotiating Television and Modernity in Rural Rajasthan Advisor: Susan S. Wadley M.A. December 2002, Cultural Anthropology Certificates of Advanced Study in South Asian Studies and Women’s Studies Concentrations: India, Globalization, Mass Media (TV), Women’s Studies Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, Portland, Maine Post-graduate Program, Fall 1997, Creative Nonfiction Writing Track Ethnographic study of Native American Basketmakers in Maine, resulted in published article “Pounding Ash” Principia College, Elsah, Illinois BA 1997, Mass Communication/World Perspectives double major, Asian Studies Minor PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Foundations of Intercultural Learning & Teaching, January-March 2018, online course • Participated in eight-week online course in intercultural communication taught by Dr. Tara Harvey Institute for Curriculum and Campus Internationalization, Indiana University, Bloomington May 21-24 2017 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Principia College Global Studies Department, Elsah, Illinois Chair, July 2015 - present • Hired second FTE for Global Studies (2016) • Doubled the major from 10-22 students (2010-2018) • Created the major’s first curriculum map with executive board -

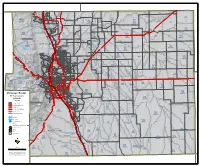

Drainage Basins D R R a F A

EEllbbeerrtt CCoouunnttyy Coommeerrccee Rdd d d R R h h Douglas County a Douglas County a m m rr a a d d D R D R R R t t Fremont C k Fremont P C k r P r w e w W rr e e h a W e a av h E h avy e h y e E s O d d s st rs Oa DD d r k r o d t r a n e r o n relllla ee k Dr a K r n Fort e L K n Fort L B kk e Carpenter n C B Carpenter R n C b R Bald u L b ee u Bald L r S v Plum r v ee Plum l k h i o e k h r i o e l r RAMAH D g rr l l D g l n a l n a d T G G T i h r G d G ok St h r CC o E ro St r B ok i Bro o r t i E t n d d Sundance Mountain d d e n r E p e r E Creek kk p R oo W g E Creek H R g E W ll v Mountain w v H w R u R R M ountain R u r Creek r Creek W EE t W r cc o H i r h t o H i e e a Antelope h n D a d n e i D e p n a d Antelope o n p o e g n a n r r g WW dd e e d g o e e d g T o H R n PLPL0400 e e T l n 8285 l e T H R T g PLPL0400 D g F m PLPL020 0 F West D u e D u m PLPL0200 PLP0600 D e v a West r a r d v t PLP0600 d t m l r a i l r h k S l k l i h rr a m S i l r l i dd g c n d r R w c r amah n E R Rd g i r a E Ramah w o T DD u i a PALMER LAKE o D T amah Rd D E R u G R d k ah R r G d RR am h * R k e E A r n d R o e n A * h oo S S o a n c e a d e n r c d cc r Creek C m r r W ee D C W m D aa s o e Creek R C l s r Ca o e o l t S a h r R t e rr b h r r d e d o b S e p dr D d e p ra D e R M l a l oss a e L R M Rock l D a l oss Rd mm L Dr e Rock Rd u DD r r l s e m a r l s lm t a u l B s r o B aa l t t s r o l t h M lh r P l r M F C S P e e e l e C S g gg a e F l e g a i l n a W Ramah Rd i l n a Rd t o A W Ramah o p t A d r C nn p d r C -

Handbook for Parents with School Age Children 2015-2016

Handbook for Parents with School Age Children 2015-2016 School Liaison Officer 135 Dover Street, Suite 1203, Airman & Family Readiness Center Peterson AFB, CO 80914 Commercial 719-556-6141 DSN 834-6141 E-mail: [email protected] January 22, 2016 1 Table of Contents WELCOME TO PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE………………………………………………………………...…………………………………4 GENERAL INFORMATION…………………………………………………………………………. ................................................................... 5 School Liaison Officer…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…5 School Locator: “Colorado Choice State”…………………………………………………………………………………………..…5 Military Interstate Children’s Compact………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 New Student Registrations and School Physical Forms…………………………………………………………………………….8 Immunizations…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Bus Schedules………………………………………………………………………………………. .................................................... 9 R.P. Lee Youth Center, Peterson AFB…………………………………………………………………………………..……………..10 Choosing a School……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 School District Maps……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...11 School/Student Report Cards…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...12 Colorado Academic Standards, Standards of Learning Tests.......……………………………………………………………….12 Special Education…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Delayed Openings – Early Closure, PTA/PTO, Impact Aid…………………………………………………………………………13 Graduation Requirements………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..14 Home Schooling………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…14 -

Women Who Would Not Be Silent

WOMEN WHO WOULD NOT BE SILENT Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910) was an influential American author, teacher, and religious leader, noted for her groundbreaking ideas about spirituality and health, which she named Christian Science. She articulated those ideas in her major work, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, first published in 1875. Four years later she founded the Church of Christ, Scientist, which today has branch churches and societies around the world. In 1908 she launched The Christian Science Monitor, a leading international newspaper, the recipient, to date, of seven Pulitzer Prizes. “Woman must not and will not be disheartened by a thousand denials or a million of broken pledges. With the assurance of faith she prays, with the certainty of inspiration she works, and with the patience of genius she waits. At last she is becoming ‘as fair as the morn, as bright as the sun, and as terrible as an army with banners’ to those who march under the black flag of oppression and wield the ruthless sword of injustice.” ~Pulpit and Press, 83:8 “Let the voice of Truth and Love be heard above the dire din of mortal nothingness, and the majestic march of Christian Science go on ad infinitum, praising God, doing the works of primitive Christianity, and enlightening the world.” ~The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, page 245 “Let it not be heard in Boston that woman, ‘last at the cross and first at the sepulchre,’ has no rights which man is bound to respect. In natural law and in religion the right of woman to fill the highest measure of enlightened understanding and the highest places in government, is inalienable, and these rights are ably vindicated by the noblest of both sexes.