When Can Impact Investing Create Real Impact? by Paul Brest & Kelly Born

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE PREPARED BY MARCH 2019 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE Preface Disclaimer Avivar Capital, LLC is a Registered Investment Adviser. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Avivar Capital, LLC and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. This website is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by Avivar Capital, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. The commentary in this presentation reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints and analyses of the Avivar Capital, LLC and employees providing such comments. It should not be regarded as a description of advisory services provided by Avivar Capital, LLC or performance returns of any Avivar Capital, LLC investments client. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Nothing on this presentation constitutes investment advice, performance data or any recommendation that any particular security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. Any mention of a particular security and related performance data is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Financing Vibrant Communities 2 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE The concept of integrating social aims with profit-making has been an emerging trend in the world for quite some time now, changing the way philanthropies think about impact and the way businesses operate. In fact, increasingly organizations “are no longer assessed based only on traditional metri- cs such as financial performance, or even the quality of their products or services. -

Oral History of William H. Draper III

Oral History of William H. Draper III Interviewed by: John Hollar Recorded: April 14, 2011 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X6084.2011 © 2011 Computer History Museum Oral History of William H. Draper III Hollar: So Bill, here I think is the challenge. There's been a great oral history done of you at Berkeley; and then you've written your book. So there's a lot of great information about you on the record. So what I thought we would try to— Draper: That's scary. I hope I say it the same way. Hollar: Well, your version of it is on the record, that's for sure. So I wanted to cover about eight areas in the hour and a half that we have. Draper: Okay. Hollar: Which is quite a bit. But I guess that's also a way of saying—we can go into as much or as little detail as you want to. But the eight areas that I was most interested in covering are your early life and your education; your early career—and with that I mean Inland Steel and meeting Pitch Johnson, and Draper, Gaither & Anderson, that section. Draper: Good. Hollar: Then Draper & Johnson—you and Pitch really getting into it together; then, of course, Sutter Hill and that very incredible fifteen-year period. Draper: Yeah, that was a good period. Hollar: A little bit of what you call "the lost decade." Draper: Okay. Hollar: Then what I call the Draper Richards Renaissance. Draper: Good. Hollar: And kind of the second chapter of venture capital for you. -

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 14 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for U.S. VC Average Deal Size by Series $516 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 10 U.S. deals leading to $357 million in total $ in Millions proceeds. This week also had 5 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $320 million, $35 compared to last week’s 4 deals resulting in $279 million in total proceeds. ▪ The U.S. VC average deal size has been significantly increasing for early and late stage VC deals. Late $30 stage VC has increased by 8.8% CAGR 2008 – 2017 while early stage VC has grown by 7.4% CAGR 2008 – 2017. (see figure) ▪ Southern Cross, a PE fund that invests in energy, pharmaceuticals and technology in Latin America, has $25 decided against restructuring its third fund after receiving some interest from its LPs. It is largely because its third fund has been a weak performer, the discount on fund stakes would have been steep and that the $20 fund wanted more time to exit. ▪ Univision has filed to withdraw its pending IPO due to “prevailing market conditions”. Univision initially filed $15 plans to IPO in 2015. ▪ New State Capital Partners has closed its second institutional fund on its $255 million hard cap. The fund $10 can invest more than $50 million equity per deal in sectors such as business services, healthcare services and industrials. -

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W. Newhall III William H. Draper III Interview Conducted and Edited by Mauree Jane Perry October, 2005 All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the National Venture Capital Association. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the National Venture Capital Association. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the National Venture Capital Association, 1655 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 850, Arlington, Virginia 22209, or faxed to: 703-524-3940. All requests should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Copyright © 2009 by the National Venture Capital Association www.nvca.org This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 2% of US GDP and was responsible for 10.4 million American jobs and 2.3 trillion in sales. -

The Bay Area Innovation System How the San Francisco Bay Area Became the World’S Leading Innovation Hub and What Will Be Necessary to Secure Its Future

The Bay Area Innovation System How the San Francisco Bay Area Became the World’s Leading Innovation Hub and What Will Be Necessary to Secure Its Future A Bay Area Science & Innovation Consortium Report produced by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute Principal Author Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute Contributing Author Olaf Groth CEO Emergent Frontiers Group LLC June 2012 Message from the BASIC Chairman For more than 50 years, the Bay Area has been a leading center for science and innovation and a global marketplace for the exchange of ideas, delivering extraordinary value for California, the nation and the world. Its success has been based on a unique confluence of research institutions, corporations, finance and people, in a culture that is open to the sharing of new ideas and willing to take significant risk to achieve extraordinary reward. The Bay Area innovation system is also highly integrated, with components that closely interact with and depend upon each other. The Bay Area Science and Innovation Consortium (BASIC), a partnership of the Bay Area’s leading public and private research organizations, has pre- pared this report to illustrate how the Bay Area’s innovation system works and to identify the issues that may impact its future success. Ensuring that success will require partnership between the public and private sectors, continued investment in the region’s core assets, and attention by state and federal policy makers. Mark Bregman Senior Vice President and CTO, Neustar, Inc. Chairman, BASIC Acknowledgements This report was prepared for the Bay Area Science & Innovation Consortium (BASIC) by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. -

Robert W Price – Detailed CV

Contact [email protected] Robert W. Price Global Entrepreneurship Institute | Executive Director www.linkedin.com/in/robertwprice Laguna Beach, California (LinkedIn) news.gcase.org/ (Company) angel.co/robertwprice (Portfolio) Summary robertwprice.com/ (Personal) DREAM IT! PLAN IT! DO IT! Top Skills Sports & Fitness "A true entrepreneur and mentor to many other entrepreneurs." Entrepreneurship - William Draper, Draper Richards Start-ups Robert W. Price enjoys world renown as an expert in the field of Languages entrepreneurial capitalism. English (Native or Bilingual) - Nearly 30 years of entrepreneurial experience Spanish (Native or Bilingual) - Strategist, innovative thought leader, public speaker, creative German (Limited Working) educator, and prolific author - Written or edited more than a dozen books Certifications - The intellectual architect for a number of exciting and innovative QuickBooks Online ProAdvisor projects around the world. Program - Early Adopter of cool stuff: LinkedIn User 179,784 QuickBooks Accounting Software - Advisor to global entrepreneurs and private equity investors: angel, Professional venture, corporate executives, board members, and chairmen. Amazon AWS Educate Program - Great multi-disciplinary entrepreneurial background. Excellent at TurboTax Software Professional critical thinking, problem identification, operations management, Google AdWords Professional venture team development, and problem solving. Consulted with venture capitalists and their start-ups, mid-cap publicly traded Honors-Awards NASDAQ -

Impact Accelerators: Strategic Options for Development and Implementation December 2015

Impact Accelerators: Strategic Options for Development and Implementation December 2015 Prepared by: Futurity Foundation in collaboration with Bogusky LLC, Boomtown, Common, University of Colorado, Boulder’s Sustainability Innovation Lab of Colorado Principal Investigator: Matthew Wilburn King Contributors: Alex Bogusky, Toby Krout, Rob Schuham, Jason Neff, Ben Webster, Kelly Fenson- Hood, and Cassie Pintal Fall 08 Impact Accelerators: Strategic Options for Development and Implementation 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 3 Overview of Types of Accelerator Programs .............................................................. 4 Tech Accelerators ................................................................................................................... 4 Corporate Accelerators .......................................................................................................... 5 Impact Accelerators ................................................................................................................ 6 Social Enterprise Recruitment and Selection ................................................................... 11 Program Offerings ................................................................................................................ 12 Business Skills Development ............................................................................................... 13 Mentorship .......................................................................................................................... -

Venture Capital Investing Conference June 3-5, 2009 the Palace Hotel • San Francisco, CA

Updated: May 7, 2009 Alexandra Scott Christina Riboldi Chief Executive Officer Executive Vice President IBF Conferences, Inc. IBF Conferences, Inc. Inter International Business Forum International Business Forum Tel: (516) 765-9005 x 300 Tel: (516) 765-9005 x 180 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 20th Annual Venture Capital Investing Conference June 3-5, 2009 The Palace Hotel • San Francisco, CA For 20 years, this conference has served as the premier industry gathering for over 400 venture capitalists and limited partners. Advisory Board Chairman: Conference Chairmen: Gary Morgenthaler Dixon Doll Navin Chaddha General Partner General Partner & Co-Founder Managing Director Morgenthaler Ventures DCM Mayfield Fund 1 Founding Advisory Board Members include: Richard Kramlich, Co-Founder & General Partner, New Enterprise Associates; Jim Swartz, General Partner, Accel; Brook Byers, General Partner, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers; Irwin Federman, General Partner, U.S. Venture Partners; Paul Denning, Founder & CEO, Denning & Co.; Sandford Robertson, General Partner, Francisco Partners; Paul Denning, Founding Partner, Denning and Company; Alan Patricof, General Partner, Greycroft Partners 2009 Advisory Board Members: ; Lip-Bu Tan, Chairman, Walden International; Todd Chaffee, General Partner, Institutional Venture Partners; Ajit Nazre, General Partner, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers; Bob Grady, Managing Director, The Carlyle Group; Susan Mason, General Partner, Onset Ventures; Navin Chaddha, Managing Director, -

Reclaiming Democracy

RECLAIMING DEMOCRACY GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE SAN FRANCISCO BAY | APRIL 1–3 RECLAIMING DEMOCRACY GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 1–3, 2 19 SAN FRANCISCO BAY 2019 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2019 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Minor adjustments have been to remarks for clarity. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team— Meghan Kennedy, Angelina Donhoff, Suzy Antounian, Claire McMahon, Carla Thorson, Julia Levin, Taytum Sanderbeck, Jarrod Sport, Laura Beatty, Sylvia Hacaj, Isaac Mora, and Lucia Johnson Seller—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Anonymous Newman’s Own Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation The David & Lucile Packard Margaret A. Cargill Foundation Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Sall Family Foundation World Bank Group SUPPORTING MEMBERS African Development Fund MEMBERS The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley William Draper III Charitable Trust Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Felipe Medina Humanity United Inter-American Development Bank International Finance Corporation MacArthur Foundation The MasterCard Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

Private Capital Public Good

PRIVATE CAPITAL PUBLIC GOOD How Smart Federal Policy Can Galvanize Impact Investing — and Why It’s Urgent JUNE 2014 US NATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD ON IMPACT INVESTING WHO WE ARE As part of the June 2013 G8 meeting, an international effort was undertaken to explore the possibilities for impact investing to accelerate economic growth and to address some of society’s most important issues. Under the auspices of that effort, the United States National Advisory Board was formed to focus on the domestic policy agenda. The board is comprised of 27 thought leaders, including private investors, entrepreneurs, foundations, academics, impact-oriented organizations, nonprofits, and intermediaries. The group’s purpose is to highlight key areas of focus for US policymakers in order to support the growth of impact investing and to provide counsel to the global policy discussion. This report is the result of a collaborative process. Each member of the National Advisory Board (NAB) brings different perspectives and priorities to this effort. Members of the NAB have participated in their capacity as individuals, rather than representatives of their organizations. The report represents the collective perspectives of the group, rather than the specific viewpoints of each individual. PRIVATE CAPITAL, PUBLIC GOOD 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A movement is afoot. It reaches across sectors and across geographies, linking small-business loans in Detroit with community development financing in Delhi. It has animated a generation of entrepreneurs and captured the imagination of world leaders. It links the social consciousness of philanthropy with the market principles of business. It’s about how the power of markets can help to scale solutions to some of our most urgent problems. -

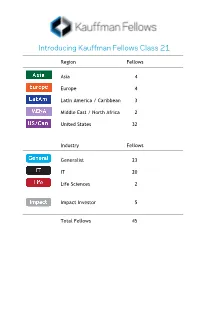

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21 Region Fellows Asia 4 Europe 4 Latin America / Caribbean 3 Middle East / North Africa 2 United States 32 Industry Fellows Generalist 23 IT 20 Life Sciences 2 Impact Investor 5 Total Fellows 45 NICOLAS BERMAN Partner KaszeK Ventures [email protected] +54 (11) 4786-3426 www.kaszek.com Professional Nik is a Partner at KaszeK Ventures, a venture capital firm investing in high-impact technology-based companies whose main focus is Latin America. In addition to capital deployment, the firm actively supports its portfolio companies through value-added strategic guidance and hands-on operational help, leveraging its partners’ successful entrepreneurial backgrounds and extensive network. Before joining KaszeK Ventures, Nik worked for 13 years at MercadoLibre, where he was VP of Advertising, VP of Marketing, Marketing Manager, and covered several roles in the company’s technology and product areas. He led several key projects in search, business intelligence (BI), user experience (UX), and SEO, and created the company’s affiliate program, which is the largest in Latin America. During all these years, Nik has also been a very active advisor and angel investor in the Latin American startup scene. Prior to MercadoLibre, Nik was a Commercial Manager at LG Electronics, where he received the “LG Global Hit Idea” award for his innovative thinking. He currently sits on the boards of several technology companies, including DogHero, Contabilizei, and Pitzi. Education/Personal Nik earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). He served as President of AMDIA (Argentina’s direct marketing association), received an Echo Award by the DMA in 2000, is currently an active mentor for Endeavor Argentina, and sits in the board of Educatina, a company focused on democratizing high-quality education across Latin America. -

Firms Lure Execs to Help Savor Bubblicious Consumer Sector

TECHNOLOGY EDITION TRACKING INNOVATION AND THE MONEY BEHIND IT » OCTOBER 2006 | VOLUME X | ISSUE 10 In This Issue Firms Lure Execs To Help Savor » Mark Cuban is hardly a maverick investor. Venture Capitalist Profile > p.5 Bubblicious Consumer Sector » Softbank Corp. maintains a U.S. BY CLANCY NOLAN presence through early-stage Softbank Capital. year ago, Jeremy Liew had a high-profile job as general manager of Venture Firm Profile > p.16 Time Warner Inc.’s Netscape division, a post he took in 2002 after stints at InterActiveCorp and CitySearch. But when a friend suggest- » Patent reform legislation might be A good medicine for venture industry. ed last October that he try venture investing, Liew became intrigued. Tech Letter > p.23 He called Eric O’Brien, a friend and general partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners. Three months later Liew joined the firm. “I spend my day with enthusiastic, knowledgeable, passionate entrepre- neurs who want to build something new,” said Liew, now a partner at the Menlo Park, Calif., firm. “It is a lot more visceral than I anticipated.” Also Inside Liew is just one of a slew of newly minted VCs who have left dream jobs at giants such as AOL, eBay Inc., Yahoo Inc. and Microsoft Corp., lured by Fund Monitor:Advent International has shifted away the high risk and potentially killer returns of venture capital investing. from early-stage venture investing > p.4 Former Yahoo executive James Slavet joined Greylock Partners as a part- Sector Watch > p.6-13 ner in April to source deals in search, mobile technology, online marketing and Consumer:Shopping sites still on VCs’ shelves advertising.