Social Entrepreneurship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit to the Barefoot College General Exposure Visit Agenda

TILONIA 2019 Visit to the Barefoot College General Exposure Visit Agenda The Barefoot College, Tilonia 305816 Madaganj, Dirstrict Ajmer, Rajasthan India. Google maps link How and When to Reach Us Contact Person: Visit Coordinator: The Barefoot College is located in the Ajmer district, between vibrant villages and yellowy mustard fields, int the central part of the rocky Mr. Brijesh Gupta +91 and dry desert of Rajsthan. 8209869426 [email protected] There are multiple and at times adventurous ways to reach us. g. FLIGHT: Kishangarh where spice jet operates a flight from Delhi everyday at 3.20 pm, there we can arrange a pick up for you at the Stella Morielli +9179 cost of around 800 ₹ 76387514 TRAIN: the closest train station will be Kishangarh where Shatabdi from Delhi arrives daily as well as many other trains. GOVT. BUS: to Kishangarh or to Patan turn on the Ajmer Jaipur Highway. If you wish to fly or arrive through Jaipur instead, a pick up will cost around 3500 ₹ ***Please note that opening times for visitors 10am to 5 pm excluding Sundays and National Holidays. Awareness If you are staying overnight we would really appreciate your Empowerment consideration for our opening times. Environmental Stewardship 1 The Footprints of the Mahatma “The future of India lies in its villages”. This is the fundamental tenet of the Barefoot Approach to sustainable rural communities, thus we propose our guests and visitors to experience living “barefoot” with humility and detachment from our daily and sometimes superfluous material needs. Be the change you want to see in the world while staying with us. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Solidarity Economies

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Solidarity Economies, Networks and the Positioning of Power in Alternative Cultural Production and Activism in Brazil: The Case of Fora do Eixo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Andrew C. Whitworth-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Hallin, Chair Professor Boatema Boateng Professor Nitin Govil Professor John McMurria Professor Toby Miller Professor Nancy Postero 2014 COPYRIGHT BY Andrew C. Whitworth-Smith 2014 Some Rights Reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/ The Dissertation of Andrew C. Whitworth-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION To Mia Jarlov, for your passion and humility, your capacity to presuppose the best in others, for your endurance and strength, and above -

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE PREPARED BY MARCH 2019 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE Preface Disclaimer Avivar Capital, LLC is a Registered Investment Adviser. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Avivar Capital, LLC and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. This website is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by Avivar Capital, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. The commentary in this presentation reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints and analyses of the Avivar Capital, LLC and employees providing such comments. It should not be regarded as a description of advisory services provided by Avivar Capital, LLC or performance returns of any Avivar Capital, LLC investments client. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Nothing on this presentation constitutes investment advice, performance data or any recommendation that any particular security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. Any mention of a particular security and related performance data is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Financing Vibrant Communities 2 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE The concept of integrating social aims with profit-making has been an emerging trend in the world for quite some time now, changing the way philanthropies think about impact and the way businesses operate. In fact, increasingly organizations “are no longer assessed based only on traditional metri- cs such as financial performance, or even the quality of their products or services. -

Oral History of William H. Draper III

Oral History of William H. Draper III Interviewed by: John Hollar Recorded: April 14, 2011 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X6084.2011 © 2011 Computer History Museum Oral History of William H. Draper III Hollar: So Bill, here I think is the challenge. There's been a great oral history done of you at Berkeley; and then you've written your book. So there's a lot of great information about you on the record. So what I thought we would try to— Draper: That's scary. I hope I say it the same way. Hollar: Well, your version of it is on the record, that's for sure. So I wanted to cover about eight areas in the hour and a half that we have. Draper: Okay. Hollar: Which is quite a bit. But I guess that's also a way of saying—we can go into as much or as little detail as you want to. But the eight areas that I was most interested in covering are your early life and your education; your early career—and with that I mean Inland Steel and meeting Pitch Johnson, and Draper, Gaither & Anderson, that section. Draper: Good. Hollar: Then Draper & Johnson—you and Pitch really getting into it together; then, of course, Sutter Hill and that very incredible fifteen-year period. Draper: Yeah, that was a good period. Hollar: A little bit of what you call "the lost decade." Draper: Okay. Hollar: Then what I call the Draper Richards Renaissance. Draper: Good. Hollar: And kind of the second chapter of venture capital for you. -

Four Revolutions in Global Philanthropy Maximilian Martin

Four Revolutions in Global Philanthropy Maximilian Martin Working Papers Vol. 1 Martin, Maximilian. 2011. ³Four Revolutions in Global Philanthropy´Impact Economy Working Paper, Vol.1 Table of Contents Philanthropy is currently undergoing four revolutions in parallel. This paper identifies and analyzes the four main fault lines which will influence the next decades of global philanthropy. All are related to what we can refer to as the market revolution in global philanthropy. As global philanthropy moves beyond grantmaking, into investment approaches that produce a social as well as a financial return, this accelerates the mainstreaming of a variety of niche activities. They marry effectiveness, social impact, and market mechanisms. 1. Global Philanthropy: A Field in Transition ............................................................................... 3 2. From Inefficient Social Capital Markets to Value-Driven Allocation ......................................... 7 3. Revolution One: Amplifying Social Entrepreneurship through Synthetic Social Business ......11 4. Revolution Two: From Microfinance to Inclusive Financial Services ......................................16 5. Revolution Three: From Development Assistance to Base-of-the-Pyramid Investments .......23 6. Revolution Four: From Classical Grantmaking to Entrepreneurial Internalization of Externalities ..............................................................................................................................29 7. Conclusion: Where Are We Headed? ....................................................................................34 -

Indian Projects Win $50K Top Tech Awards by LISA TSERING Letters to Editor Indiawest.Com November 20, 2008 02:57:00 PM Culture / Religion Sports Blogs SAN JOSE, Calif

Welcome to IndiaWest.com http://www.indiawest.com/readmore.aspx?id=622&sid=1 User name Password Remember Sign in Sign Up to add Blogs, Podcasts and more.. LATEST NEWS ADVERTISE SUBSCRIBE ARCHIVES ABOUT US CONTACT US US Indian News IndiaWest Home US Indian News News India News | | E-mail to Your Friend Print this Article Entertainment Business US INDIAN NEWS Classifieds Events Calendar Indian Projects Win $50K Top Tech Awards By LISA TSERING Letters to Editor indiawest.com November 20, 2008 02:57:00 PM Culture / Religion Sports Blogs SAN JOSE, Calif. — Projects changing the lives of millions of people in India took four of the top five prizes at the 2008 Tech Awards, presented at a black-tie gala at the San Jose Convention Podcasts Center Nov. 12. Each award comes with a $50,000 cash prize. Astrology “Big changes can come from simple and uncomplicated solutions,” said Peter Friess, president of of the Tech Museum, which has administered the prizes for the past eight years. “These winners have all seen a difference in their lives, careers and how they’ve been perceived afterwards.” A well-heeled crowd of 1,450 filled a convention center ballroom (the awards have outgrown their former venue in the Tech Museum down the street) and got the chance to peruse exhibits detailing the work of the 25 finalists, or Tech Laureates. Muhammad Yunus, the Bangladesh-born founder of the Grameen Bank and the winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, was on hand to receive another prestigious honor — the James C. Morgan Global Humanitarian Award. -

Harish Hande Dr

Case: Solar Electric Light Co. India –Harish Hande Dr. Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Higher Education, Emerging Technologies, and Innovation Entrepreneurship © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor Case: SELCO -Harish Hande 1 The Problem • An estimated 1.2 billion people – 17% of the global population – did not have access to electricity in 2013, 84 million fewer than in the previous year. – Many more suffer from supply that is of poor quality. – More than 95% of those living without electricity are in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and developing Asia, and they are predominantly in rural areas (around 80% of the world total). – While still far from complete, progress in providing electrification in urban areas has outpaced that in rural areas two to one since 2000. • International Energy Agency • http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/resources/energydevelopment/energyaccessdatabase/ • Of those about 400 million are in India alone. Entrepreneurship © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor Case: SELCO -Harish Hande 2 Harish Hande ‘98 ‘00 • UML MS ‘98 renewable energy engineering • UML PhD ‘00 in mechanical engineering (energy) • co-founded Solar Electric Light Co. India in 1995. – As SELCO’s managing director, he has pioneered access to solar electricity for more than half a million people in India, where more than half the population does not have electricity, through customized home-lighting systems and innovative financing. • Hande received the 2011 Magsaysay Award, widely considered Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize, • One of 21 Young Leaders for India’s 21st Century by Business Today • Social Entrepreneur of the Year for 2007 by the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship and the Nand and Jeep Khemkha Foundation. -

December, 2015

Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia Regional Cooperation Newsletter- South Asia October- December, 2015 Editor Prof. P. K. Shajahan Ph.D. Guest Editor Prabhakar Jayaprakash 1 Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia Regional Cooperation Newsletter – South Asia is an online quarterly newsletter published by the Inter- national Council on Social Welfare – South Asia Region. Currently, it is functioning from the base of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. The content of this newsletter may be freely reproduced or cited provided the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in this publication are those of the respective author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of ICSW. CONTENTS Editor’s note 01 Special article Sri Lanka: The Road to Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation 03 -Prabhakar Jayaprakash Articles The Ambitiousness of Jan Dhan Yojana 10 - Srishti Kochhar, Anmol Somanchi, and Vipul Vivek Myanmar: On Road to the Future 15 -Kaveri Commentaries Contextualizing Sri Lanka 19 - G.V.D Tilakasiri Masculinity of Nation States: The Case of Nepal 22 -Abhishek Tiwari News and Events 26 2 Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia EDITOR’S NOTE Since the last few years, South Asian countries are said to be in a political transition. The end of civil war amidst criticism of widespread human rights violations followed by presidential elections in Sri Lanka two years ahead of its schedule brought surprise to the incumbent President Mahinda Rajapaksa with his erstwhile Minister of Health, Maithripala Sirisena fielded by United National Party (UNP)-led opposition coalition being elected to the top post. Pakistan has seen Nawaz Sharif, once on Political exile, returning to power for his third term in the 2013 presidential elections. -

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

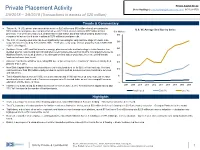

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 14 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for U.S. VC Average Deal Size by Series $516 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 10 U.S. deals leading to $357 million in total $ in Millions proceeds. This week also had 5 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $320 million, $35 compared to last week’s 4 deals resulting in $279 million in total proceeds. ▪ The U.S. VC average deal size has been significantly increasing for early and late stage VC deals. Late $30 stage VC has increased by 8.8% CAGR 2008 – 2017 while early stage VC has grown by 7.4% CAGR 2008 – 2017. (see figure) ▪ Southern Cross, a PE fund that invests in energy, pharmaceuticals and technology in Latin America, has $25 decided against restructuring its third fund after receiving some interest from its LPs. It is largely because its third fund has been a weak performer, the discount on fund stakes would have been steep and that the $20 fund wanted more time to exit. ▪ Univision has filed to withdraw its pending IPO due to “prevailing market conditions”. Univision initially filed $15 plans to IPO in 2015. ▪ New State Capital Partners has closed its second institutional fund on its $255 million hard cap. The fund $10 can invest more than $50 million equity per deal in sectors such as business services, healthcare services and industrials. -

Medical Examiners Finding

Harris County Archives Houston, Texas Finding Aid HARRIS COUNTY MEDICAL EXAMINER’S OFFICE RECORDS CR41 (1954 - 2012) Acquisition: Office of the Medical Examiner Accession Numbers: 2004.006, 2004.016, 2004.001, 2005.008, 2005.029, 2005.035, 2006.034, 2007.006, 2007.036, 2008.027 Citation: [Identification of Item], Harris County Medical Examiner’s Office, Harris County Archives, Houston, Texas. Agency History: During the Republic of Texas and until the Constitution of 1869, the office of coroner functioned primarily to identify homicides. In 1955 the Texas Legislature passed the Baker Bill which allowed counties with a population greater than 250,000 to establish an Office of Medical Examiner to assume those duties previously conducted by the Justices of the Peace. The revision of the Code of Criminal Procedure in 1965 mandated that counties with populations greater than 500,000 shall establish a Medical Examiner’s office. Currently, the statute requires counties of over 1,000,000 to establish a Medical Examiner’s office. Those counties with medical schools were exempted from the law. The Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 49.25, mandates the Medical Examiner to determine the cause and manner of death in all cases of accident, homicide, suicide, and undetermined death. In cases of natural death, when the person is not under a doctor’s care, or the person passes away in less than 24 hours after admission to a hospital, an institution, a prison, or a jail, the Medical Examiner must be notified. Harris County, although it had a medical school, was among the first counties to opt for a medical-examiner system.