Private Capital Public Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 Health Programs Financial Information Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report

Celebrating 30 years of waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope 30 ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 HEALTH PROGRAMS FINANCIAL INFORMATION Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report . 64 Eradication and Elimination . 20 Financial Statements . 65 Partner for Village-Based Notes to Statements . 70 Health Care Delivery . 22 OUR COMMUNITY The Carter Center at a Glance . 2. Voice for Mental Health Care . 24 The Carter Center Around Aontents Message from President Health Year in Review . 26 the World . 84 CJimmy Carter . 3 PHILANTHROPY Senior Staff . 86 Interns . 86 Our Mission . 4 A Message About Our Donors . 32 A Letter from the Officers . 5 International Task Force for Donors with Cumulative Lifetime Disease Eradication . 87 Giving of $1 Million or More . 33 PEACE PROGRAMS Friends of the Inter-American Pioneer of Election Observation . 8 Donors During 2010–2011 . 34 Democratic Charter . 87 Trusted Broker for Peace . 10 Ambassadors Circle . 48 Mental Health Boards . 88 Champion for Human Rights . 12 Legacy Circle . 58 Board of Councilors . 89 Peace Year in Review . 14 Founders . 61 Board of Trustees . 92 A woman works at a small-scale subsistence mine in the province of Katanga, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo . The Carter Center’s work in the country is raising awareness about the nation’s lucrative mining industry, which generates huge profits while impoverished local communities receive few of the benefits . 1 The Carter Center at a Glance Overview • Strengthening international standards for human rights The Carter Center was founded in 1982 by former U.S. and the voices of individuals defending those rights in President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, in their communities worldwide partnership with Emory University, to advance peace and • Pioneering new public health approaches to preventing health worldwide. -

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE PREPARED BY MARCH 2019 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE Preface Disclaimer Avivar Capital, LLC is a Registered Investment Adviser. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Avivar Capital, LLC and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. This website is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by Avivar Capital, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. The commentary in this presentation reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints and analyses of the Avivar Capital, LLC and employees providing such comments. It should not be regarded as a description of advisory services provided by Avivar Capital, LLC or performance returns of any Avivar Capital, LLC investments client. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Nothing on this presentation constitutes investment advice, performance data or any recommendation that any particular security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. Any mention of a particular security and related performance data is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Financing Vibrant Communities 2 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE The concept of integrating social aims with profit-making has been an emerging trend in the world for quite some time now, changing the way philanthropies think about impact and the way businesses operate. In fact, increasingly organizations “are no longer assessed based only on traditional metri- cs such as financial performance, or even the quality of their products or services. -

Oral History of William H. Draper III

Oral History of William H. Draper III Interviewed by: John Hollar Recorded: April 14, 2011 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X6084.2011 © 2011 Computer History Museum Oral History of William H. Draper III Hollar: So Bill, here I think is the challenge. There's been a great oral history done of you at Berkeley; and then you've written your book. So there's a lot of great information about you on the record. So what I thought we would try to— Draper: That's scary. I hope I say it the same way. Hollar: Well, your version of it is on the record, that's for sure. So I wanted to cover about eight areas in the hour and a half that we have. Draper: Okay. Hollar: Which is quite a bit. But I guess that's also a way of saying—we can go into as much or as little detail as you want to. But the eight areas that I was most interested in covering are your early life and your education; your early career—and with that I mean Inland Steel and meeting Pitch Johnson, and Draper, Gaither & Anderson, that section. Draper: Good. Hollar: Then Draper & Johnson—you and Pitch really getting into it together; then, of course, Sutter Hill and that very incredible fifteen-year period. Draper: Yeah, that was a good period. Hollar: A little bit of what you call "the lost decade." Draper: Okay. Hollar: Then what I call the Draper Richards Renaissance. Draper: Good. Hollar: And kind of the second chapter of venture capital for you. -

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 14 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for U.S. VC Average Deal Size by Series $516 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 10 U.S. deals leading to $357 million in total $ in Millions proceeds. This week also had 5 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $320 million, $35 compared to last week’s 4 deals resulting in $279 million in total proceeds. ▪ The U.S. VC average deal size has been significantly increasing for early and late stage VC deals. Late $30 stage VC has increased by 8.8% CAGR 2008 – 2017 while early stage VC has grown by 7.4% CAGR 2008 – 2017. (see figure) ▪ Southern Cross, a PE fund that invests in energy, pharmaceuticals and technology in Latin America, has $25 decided against restructuring its third fund after receiving some interest from its LPs. It is largely because its third fund has been a weak performer, the discount on fund stakes would have been steep and that the $20 fund wanted more time to exit. ▪ Univision has filed to withdraw its pending IPO due to “prevailing market conditions”. Univision initially filed $15 plans to IPO in 2015. ▪ New State Capital Partners has closed its second institutional fund on its $255 million hard cap. The fund $10 can invest more than $50 million equity per deal in sectors such as business services, healthcare services and industrials. -

ONFI-2017-990-PF.Pdf

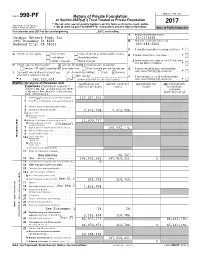

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2017 G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , A Employer identification number Omidyar Network Fund, Inc 20-1173866 1991 Broadway St #200 B Telephone number (see instructions) Redwood City, CA 94063 650-482-2500 C If exemption application is pending, check here. G G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D1Foreign organizations, check here. G Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation . G H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here. G IJFair market value of all assets at end of year Accounting method: CashX Accrual (from Part II, column (c), line 16) Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination G $ 545,202,008. (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here. G Part I Analysis of Revenue and (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitable columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes sarily equal the amounts in column (a) (cash basis only) (see instructions).) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received (attach schedule). -

Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should Or Could to Stop Online Fraud?

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 2 Article 8 3-2000 Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Communications Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, James M. (2000) "Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud?," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol52/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 454 II. COMPLAINTS OF ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD INCREASE AS THE PERPETRATORS BECOME MORE CREATV ................................. 455 A. Statistical Evidence of the Increase in Online Auction Fraud.................................................................................... 455 B. Online Auction Fraud:How Does It Happen? ..................... 457 1. Fraud During the Bidding Process .................................. 457 2. Fraud After the Close of the Auction .............................. 458 IlL VARIOUS PARTES ARE ATrEMPTNG TO STOP ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD .......................................................................... 459 A. The Online Auction Houses' Efforts to Self-regulate........... -

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W. Newhall III William H. Draper III Interview Conducted and Edited by Mauree Jane Perry October, 2005 All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the National Venture Capital Association. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the National Venture Capital Association. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the National Venture Capital Association, 1655 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 850, Arlington, Virginia 22209, or faxed to: 703-524-3940. All requests should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Copyright © 2009 by the National Venture Capital Association www.nvca.org This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 2% of US GDP and was responsible for 10.4 million American jobs and 2.3 trillion in sales. -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

The Bay Area Innovation System How the San Francisco Bay Area Became the World’S Leading Innovation Hub and What Will Be Necessary to Secure Its Future

The Bay Area Innovation System How the San Francisco Bay Area Became the World’s Leading Innovation Hub and What Will Be Necessary to Secure Its Future A Bay Area Science & Innovation Consortium Report produced by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute Principal Author Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute Contributing Author Olaf Groth CEO Emergent Frontiers Group LLC June 2012 Message from the BASIC Chairman For more than 50 years, the Bay Area has been a leading center for science and innovation and a global marketplace for the exchange of ideas, delivering extraordinary value for California, the nation and the world. Its success has been based on a unique confluence of research institutions, corporations, finance and people, in a culture that is open to the sharing of new ideas and willing to take significant risk to achieve extraordinary reward. The Bay Area innovation system is also highly integrated, with components that closely interact with and depend upon each other. The Bay Area Science and Innovation Consortium (BASIC), a partnership of the Bay Area’s leading public and private research organizations, has pre- pared this report to illustrate how the Bay Area’s innovation system works and to identify the issues that may impact its future success. Ensuring that success will require partnership between the public and private sectors, continued investment in the region’s core assets, and attention by state and federal policy makers. Mark Bregman Senior Vice President and CTO, Neustar, Inc. Chairman, BASIC Acknowledgements This report was prepared for the Bay Area Science & Innovation Consortium (BASIC) by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. -

Robert W Price – Detailed CV

Contact [email protected] Robert W. Price Global Entrepreneurship Institute | Executive Director www.linkedin.com/in/robertwprice Laguna Beach, California (LinkedIn) news.gcase.org/ (Company) angel.co/robertwprice (Portfolio) Summary robertwprice.com/ (Personal) DREAM IT! PLAN IT! DO IT! Top Skills Sports & Fitness "A true entrepreneur and mentor to many other entrepreneurs." Entrepreneurship - William Draper, Draper Richards Start-ups Robert W. Price enjoys world renown as an expert in the field of Languages entrepreneurial capitalism. English (Native or Bilingual) - Nearly 30 years of entrepreneurial experience Spanish (Native or Bilingual) - Strategist, innovative thought leader, public speaker, creative German (Limited Working) educator, and prolific author - Written or edited more than a dozen books Certifications - The intellectual architect for a number of exciting and innovative QuickBooks Online ProAdvisor projects around the world. Program - Early Adopter of cool stuff: LinkedIn User 179,784 QuickBooks Accounting Software - Advisor to global entrepreneurs and private equity investors: angel, Professional venture, corporate executives, board members, and chairmen. Amazon AWS Educate Program - Great multi-disciplinary entrepreneurial background. Excellent at TurboTax Software Professional critical thinking, problem identification, operations management, Google AdWords Professional venture team development, and problem solving. Consulted with venture capitalists and their start-ups, mid-cap publicly traded Honors-Awards NASDAQ -

2019 Form 990-PF

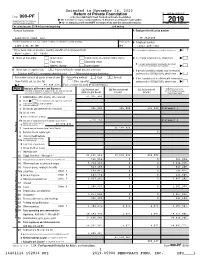

Extended to November 16, 2020 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 2019 Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2019 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number Democracy Fund, Inc. 38-3926408 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 1200 17th St NW 300 (202) 420-7943 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ~ | Washington, DC 20036 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~ | Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~ | X H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~ | X I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~ | | $ 87,348,415. -

A Conversation with Hawai'i's Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai'i International Confere

Volume 33, Number 1 Spring 2010 INSIDE: Be True to Your School | A Conversation with Hawai‘i’s Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai‘i International Conference on System Sciences to New Heights DEAn’s MessAGE “We are proud to announce that our undergraduate program has, for the first time, been named as one of the nation’s top business programs by Bloomberg BusinessWeek.” Aloha, Conference on System Sciences into nation’s best by Bloomberg BusinessWeek. The Shidler College of Business one of the world’s leading gatherings on This is truly a credit to our entire faculty is a special place where people of all information systems applications. and staff who have worked tirelessly to cultures and backgrounds come together For those of you who are aspiring strengthen our programs, student services, to share ideas, dreams and business entrepreneurs, be sure to check out the internships and career placement. aspirations. Our global community of excerpts from our exclusive interview It has been a remarkable six months alumni, students, faculty and business with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. As the and we thank you for sharing an interest professionals lies at the heart of our featured speaker for the Kı¯papa i ke Ala in all that we have accomplished. As success and is what makes this such a Lecture, he inspired us all to dream big. always, we hope that you enjoy this issue unique place to learn, grow and develop. Shidler pride continues to reign of Shidler Business. We welcome your The stories and articles in this issue of strong among our alumni.