The Bottom Line Investing for Impact on Economic Mobility in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit

Funding for Social Enterprises in Detroit: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE PREPARED BY MARCH 2019 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE Preface Disclaimer Avivar Capital, LLC is a Registered Investment Adviser. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Avivar Capital, LLC and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. This website is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by Avivar Capital, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. The commentary in this presentation reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints and analyses of the Avivar Capital, LLC and employees providing such comments. It should not be regarded as a description of advisory services provided by Avivar Capital, LLC or performance returns of any Avivar Capital, LLC investments client. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Nothing on this presentation constitutes investment advice, performance data or any recommendation that any particular security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. Any mention of a particular security and related performance data is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Financing Vibrant Communities 2 FUNDING FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN DETROIT: ASSESSING THE LANDSCAPE The concept of integrating social aims with profit-making has been an emerging trend in the world for quite some time now, changing the way philanthropies think about impact and the way businesses operate. In fact, increasingly organizations “are no longer assessed based only on traditional metri- cs such as financial performance, or even the quality of their products or services. -

Introduction to Social Enterprise & the Triple Bottom Line the Triple Bottom

Introduction to Social Enterprise & the Triple Bottom Line Drew Tulchin Managing Partner Social Enterprise Associates Webinar for Bankers without Borders Nov 30, 2012 About Social Enterprise Associates Consulting firm ‐ Registered ‘B Corp’ This network of experts offers consulting & capital raising to triple bottom line efforts ‐ for people, profits, planet. Registered ‘B Corporation’ , recognized: 2011 'One of the Best for the World‘ Small Businesses 2012 Honoree, Sustainable Business of the Year Drew Tulchin, Managing Partner, MBA • Former Program Officer, Grameen Foundation • Written >100 business/strategic plans; efforts raised >$100 million • Biz plan winner, Global Social Venture Comp; raised $1.2 mil. in social investment • Judge in international social enterprise & social business competitions Consulting Examples World Food Program: Investigated how to better engage private sector to raise $400 million. Wrote white paper on public‐private partnerships The SEEP Network: Worked with 5 int’l NGOs to develop business plans, hone products, enter new markets, & link to $ in the global North Future of Fish: Capital advisory for social entrepreneurs launching market‐based initiatives that drive sustainability, effic iency, and tbilittraceability in the seafdfood supply chihain. Plan International: Contributed to national studies in W. Africa on economic sector growth opportunities for young adults. Identified growth markets for 50,000 jobs in 3 years SW Native Green Loan Fund: Structured fund to involve small fdifoundations in public‐private -

2016 Annual Report

SUSTAINABILITY CIRCULAR ECONOMY CLIMATE RESILIENCY SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Education and resources for novice and advanced sustainable business programs. Regular WMSBF Monthly Membership Meetings occur on the second Monday of most months, with additional conferences, workshops, and mixers scheduled throughout the year in West and Southwest Michigan. Learn more about West Michigan Sustainable Business Forum at: wmsbf.org 2016 A complete schedule of upcoming events can be found at: wmsbf.org/events P.O. Box 68696 Grand Rapids, MI 49516 616.422.7963 Twenty-two years of promoting business practices that demonstrate A 501c3 non-profit organization. environmental stewardship, economic vitality, and social responsibility. TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Letter Celebrating our work .......................................................................................................................... 3 Board of Directors and Staff Meet the forum leadership ................................................................................................................ 4 Twenty-Two Years of WMSBF The forum was one of the first programs of its kind in the nation and has helped establish West Michigan as a national hub of sustainable businesss ........ 5 WMSBF Annual Report Success in 2016 and goals for the year ahead ........................................................................... 6 West Michigan Sustainable Business of the Year Finalists for the 2016 Sustainable Business of the Year and the Champion and Change Agent Special Recognition -

Oral History of William H. Draper III

Oral History of William H. Draper III Interviewed by: John Hollar Recorded: April 14, 2011 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X6084.2011 © 2011 Computer History Museum Oral History of William H. Draper III Hollar: So Bill, here I think is the challenge. There's been a great oral history done of you at Berkeley; and then you've written your book. So there's a lot of great information about you on the record. So what I thought we would try to— Draper: That's scary. I hope I say it the same way. Hollar: Well, your version of it is on the record, that's for sure. So I wanted to cover about eight areas in the hour and a half that we have. Draper: Okay. Hollar: Which is quite a bit. But I guess that's also a way of saying—we can go into as much or as little detail as you want to. But the eight areas that I was most interested in covering are your early life and your education; your early career—and with that I mean Inland Steel and meeting Pitch Johnson, and Draper, Gaither & Anderson, that section. Draper: Good. Hollar: Then Draper & Johnson—you and Pitch really getting into it together; then, of course, Sutter Hill and that very incredible fifteen-year period. Draper: Yeah, that was a good period. Hollar: A little bit of what you call "the lost decade." Draper: Okay. Hollar: Then what I call the Draper Richards Renaissance. Draper: Good. Hollar: And kind of the second chapter of venture capital for you. -

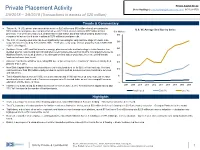

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/5/2018 – 3/9/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 14 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for U.S. VC Average Deal Size by Series $516 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 10 U.S. deals leading to $357 million in total $ in Millions proceeds. This week also had 5 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $320 million, $35 compared to last week’s 4 deals resulting in $279 million in total proceeds. ▪ The U.S. VC average deal size has been significantly increasing for early and late stage VC deals. Late $30 stage VC has increased by 8.8% CAGR 2008 – 2017 while early stage VC has grown by 7.4% CAGR 2008 – 2017. (see figure) ▪ Southern Cross, a PE fund that invests in energy, pharmaceuticals and technology in Latin America, has $25 decided against restructuring its third fund after receiving some interest from its LPs. It is largely because its third fund has been a weak performer, the discount on fund stakes would have been steep and that the $20 fund wanted more time to exit. ▪ Univision has filed to withdraw its pending IPO due to “prevailing market conditions”. Univision initially filed $15 plans to IPO in 2015. ▪ New State Capital Partners has closed its second institutional fund on its $255 million hard cap. The fund $10 can invest more than $50 million equity per deal in sectors such as business services, healthcare services and industrials. -

Integrating Human Health Into Urban and Transport Planning

Mark Nieuwenhuijsen Haneen Khreis Editors Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning A Framework Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning Mark Nieuwenhuijsen • Haneen Khreis Editors Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning A Framework Editors Mark Nieuwenhuijsen Haneen Khreis Barcelona Institute for Global Health Texas A&M Transportation Institute, Center ISGlobal for Advancing Research in Transportation Barcelona, Spain Emissions, Energy, and Health College Station, TX, USA ISBN 978-3-319-74982-2 ISBN 978-3-319-74983-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74983-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018942501 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Triple Bottom Line Preliminary Feasibility Study of the GM Oshawa Facility: Possibilities for Sustainable Community Wealth

Triple Bottom Line Preliminary Feasibility Study of the GM Oshawa Facility: Possibilities for Sustainable Community Wealth September 13, 2019 . Germany's Post Office (Deutsche Post) developed and began manufacturing Streetscooter battery electric vans in 2016 to replace its 70,000 vehicle fleet (photo: Reuters 2017). Russ Christianson 1696 9th Line West, Campbellford, Ontario, Canada K0L 1L0 705-653-0527 [email protected] An electronic version of this report is available at: http://www.greenjobsoshawa.ca/feasibility.html Triple Bottom Line Preliminary Feasibility Study of the GM Oshawa Facility: Possibilities for Sustainable Community Wealth Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 2 2.0 Summary Overview ...................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Canada’s Auto Manufacturing Industry ..................................................................... 10 4.0 Triple Bottom Line Analysis and Methodology .......................................................... 13 4.1 Economic Situation ............................................................................................................. 14 4.2 Socio-political Situation ...................................................................................................... 19 4.3 Environmental Situation ..................................................................................................... 23 5.0 Preliminary -

Microfinance & the Double Bottom Line

Copenhagen Business School May 2012 Microfinance & the Double Bottom Line A study on how the Microfinance Sector can prevent Mission-Drift Author: Michael Fhima Cand.Merc.Int Supervisor: Peter Wad Number of pages : 111 Number of units: 179.862 Master Thesis Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Abbreviations and explanations………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Research Question………………………………………………………………………………...6 Definitions and Explanations …………………………………………………………………….7 Delimitation……………………………………………………………………………………….7 Structure of thesis…………………………………………………………………………………7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………9 Research purpose………………………………………………………………………………….9 Research design…………………………………………………………………………………...9 Data gathering……………………………………………………………………………………10 Primary data……………………………………………………………………………..10 Secondary data…………………………………………………………………………..10 Methodological approach in two research papers………………………………………………...11 ‘State of Practice in Social Performance Reporting and Management’…………………12 ‘Microfinance Synergies and Trade-offs’……………………………………………….12 Data Structure…………………………………………………………………………………….13 Research strategy…………………………………………………………………………………13 Choice of theories………………………………………………………………………………………...14 CSR in GCV – Principal / Agent…………………………………………………………………14 Governing through Standards…………………………………………………………………….17 Multistakeholder CSR…………………………………………………………………………….18 Theoretical Framework…………………………………………………………………………...19 Validity and reliabilty……………………………………………………………………………..19 -

Time to Touch up the CV? Beeb Launches Search for New Director General

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY PLOUGHING AHEAD 30 YEARS LATER THE WIMBLEDON LOOK LAND ROVER DISCOVERY TO HEAD BACK TO HITS A LANDMARK P24 MERTON HOME P26 TUESDAY 11 FEBRUARY 2020 ISSUE 3,553 CITYAM.COM FREE HACKED OFF US ramps up China TREASURY TO spat with fresh Equifax charges SET OUT CITY BREXIT PLAN EXCLUSIVE Beyond Brexit, it will also consider “But there will be differences, not CATHERINE NEILAN the industry’s future in relation to least because as a global financial cen- worldwide challenges such as emerg- tre the UK needs to keep pace with @CatNeilan ing technologies and climate change. and drive international standards. THE GOVERNMENT will insist on the Javid sets out the government’s Our starting point will be what’s right right to diverge from EU financial plans to retain regulatory autonomy for the UK.” services regulation as part of a post- while seeking a “reliable equivalence He also re-committed to concluding Brexit trade deal with Brussels. process”, on which a “durable rela- “a full range of equivalence assess- Writing exclusively in City A.M. today, tionship” can be built. ments” by June of this year, in order to chancellor Sajid Javid says the “Of course, each side will only give the system sufficient stability City “will no longer be a rule- grant equivalence if it believes ahead of the end of transition. taker” and reveals that the other’s regulations are One senior industry figure told City ministers are working on compatible,” the chancel- A.M. that while a white paper was EMILY NICOLLE Zhiyong, Wang Qian, Xu Ke and Liu Le, a white paper setting lor writes. -

CSR Communication: a Study of Multinational Mining Companies in Southern Ghana

CSR Communication: A Study of Multinational Mining Companies in Southern Ghana Joe Prempeh Owusu-Agyemang, MPharm, MBA & MRes 2017 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Business Department, Kingston University, London. Supervisors: Dr Fatima Annan-Diab Dr Nina Seppala i Abstract In recent years, there has been significant interest in communication on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (Tehemar, 2012; Bortree, 2014). Yet, it is impractical to assume a one- size-fits-all definition for CSR (Crane and Matten, 2007; Walter, 2014). Therefore, this becomes an important area for research as CSR communications play a vital role in any CSR strategy in the business world, more especially in Ghana. Consequently, a good CSR communication can address the increasing cynicism about CSR when it is done effectively (Du et al., 2010; Kim and Ferguson, 2014). While a body of research exists about CSR communication at a theoretical level (Brugger, 2010; Schmeltz, 2012), there is a lack of empirical research investigating the topic in a particular policy and cultural content (Emel et al., 2012). The aim of this study was to address the limited research on CSR communication in Ghana. It empirically investigated whether the CSR dimensions (Triple Bottom Line) and effective CSR message components are positively linked with CSR stakeholder’ approval. The effects of individual characteristics including education and gender were also tested on the relationships. The study integrates insights from stakeholder theory (Vaaland et al., 2008; Wang, 2008) supported by both legitimacy theory (Perk et al., 2013) and institutional theory (Suddaby, 2013) to explain the planned base for CSR communication. -

The Triple Bottom Line by Andrew Savitz with Karl Weber John Wiley, 2006

The Triple Bottom Line by Andrew Savitz with Karl Weber John Wiley, 2006 Reviewed by David W. Gill www.ethixbiz.com Andrew Savitz runs Sustainable Business Strategies, an independent advisory firm in Boston. He has previously worked for PriceWaterhouseCoopers and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. With the research and writing assistance of Karl Weber, Savitz has produced a wonderful description of The Triple Bottom Line: How Today’s Best-Run Companies Are Achieving Economic, Social, and Environmental Success---and How You Can Too. The notion of a “triple bottom line” has been increasingly important since John Elkington’s Cannibals With Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business came out in 1997. The triple bottom line consists of financial profit (or success), social justice, and environmental protection. It is sometimes summarized as “Profits, People, and Planet.” An intimately related concept is “sustainability”---corporations that are built to last, societies that are stable and just, and a global natural environment that is in a healthy equilibrium. The basic argument is that we live in a time when a narrow, short-term focus on the financial bottom line alone will generate dysfunctions among people and in the environment that will come back to bite the corporation. Savitz is not crazy about corporate social responsibility or corporate philanthropy because their focus is too narrowly on a more-or-less one way street benefit to society, unrelated to the business. Sustainability and the “3BL” are, instead, about mutual benefits flowing in all three directions. The challenge is to find the sustainability “sweet spot” (think golf) where all three interests coincide. -

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W. Newhall III William H. Draper III Interview Conducted and Edited by Mauree Jane Perry October, 2005 All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the National Venture Capital Association. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the National Venture Capital Association. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the National Venture Capital Association, 1655 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 850, Arlington, Virginia 22209, or faxed to: 703-524-3940. All requests should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Copyright © 2009 by the National Venture Capital Association www.nvca.org This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 2% of US GDP and was responsible for 10.4 million American jobs and 2.3 trillion in sales.