Digital Archaeology and the Neolithic of the Peak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Derbyshire Attractions

Attractions in Derbyshire Below is a modified copy of the index to the two folders full of 100 leaflets of attractions in Derbyshire normally found in the cottages. I have also added the web site details as the folders with the leaflets in have been removed to minimise infection risks. Unless stated, no pre-booking is required. 1) Tissington and High Peak trail – 3 minutes away at nearest point https://www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/visiting/places-to-visit/trails/tissington-trail 2) Lathkill Dale 10 minutes away – a popular walk down to a river from nearby Monyash https://www.cressbrook.co.uk/features/lathkill.php 3) Longnor 10 minutes away – a village to the north along scenic roads. 4) Tissington Estate Village 15 minutes away – a must, a medieaval village to wander around 5) Winster Market House, 17 minutes away (National Trust and closed for time-being) 6) Ilam Park 19 minutes away (National Trust - open to visitors at any time) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/ilam-park-dovedale-and-the-white-peak 7) Haddon Hall 19 minutes away https://www.haddonhall.co.uk/ 8) Peak Rail 20 minutes away https://www.peakrail.co.uk/ 9) Magpie Mine 20 minutes away https://pdmhs.co.uk/magpie-mine-peak-district/ 10) Bakewell Church 21 minutes 11) Bakewell Museum 21 minutes open tuesday, wednesday Thursday, saturday; https://www.oldhousemuseum.org.uk/ 12) Thornbridge brewery Shop 23 minutes https://thornbridgebrewery.co.uk/ 13) Thornbridge Hall – open 7 days a week https://www.thornbridgehall.co.uk 14) Cauldwells Mill – Rowsley 23 minutes upper floors of mill -

LOCATION Lilac Collage. Main Street PREVIOUSAPP

CODE No NPDDD0102016 I P.FILE No. 10210 RECEIVED AT PDNPA OS MAP No. 1069 GRIDREF 1121 6993 8 Jan 2002 APPLICANT c/o AGENT PLOTTED Mr & Mrs P Yarwood Mr B Froggall 8 Jan 2002 Lilac Collage 41 Snitterton Road MC Main Street MATLOCK ENTERED BY Chelmorton Derbyshire NR BUXTON LMR Derbyshire CERTIFICATE POSTCODE SK179SK POSTCODEDE43LZ A Tel No. Tel No. 01629583847 PROPOSED LAND USE HSLD APPL TYPE Full PROPOSAL Alteration to front elevation and creation of vehicular access EXISTING LAND USE LOCATION Lilac Collage. Main Street PREVIOUSAPP PARISH ChelmortJ.' PLANNING ADVERT DATE 18 Ja" 2002 LAST ADVERT DATE 8 Feb 2002 OFFICER CONSTRAINTS Conservation Area ALN TCP3 DRAFT CONSULTATIONS DATE SENT DATEREPLY(- _ 9 Jan 2002 Cnelmorton Parish Council DELEGATED 9 Jan 2002 Derbysn:re Dales Distnct Council Yes Derbyshire County Council (Highways) 9 Jan 2002 Z ,;/ DEEMED REFUSAL DATE 5 Mar 2002 13 WEEKS DATE 14 Apr 2002 COMMITTEE DECISION ~ J:i.,~ APPEAL Date lodged Decision Date ENFORCEMENT RECORD CARD This card should be filed immediately in front of the decision notice which in turn should be in front of a set ofapproved plans. NPI I----+l'NELDDnt n 'I n2 I 0 1 6 The following amendments have been formally agreed by the planning officer since the issue of the decision notice: DATE DETAILS The following conditions have been formally complied with since the issue of the decision notice: DATE COND.NO. DETAILS l I I SITE VISIT RECORD DATE INSP PROGRESS DEPARTURES KEY DATES TO NOTE KEY FACTORS TO WATCH DATE DETAILS DETAILS PLANNING DECISION NOTICE Tel: 01629 816200 Fax: 01629 816310 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.peakdistriet.org Minieom: 01629 816319 Aldero House. -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council

Proposed Revised Wards for Derbyshire Dales District Council October 2020 The ‘rules’ followed were; Max 34 Cllrs, Target 1806 electors per Cllr, use of existing parishes, wards should Total contain contiguous parishes, with retention of existing Cllr total 34 61392 Electorate 61392 Parish ward boundaries where possible. Electorate Ward Av per Ward Parishes 2026 Total Deviation Cllr Ashbourne North Ashbourne Belle Vue 1566 Ashbourne Parkside 1054 Ashbourne North expands to include adjacent village Offcote & Underwood 420 settlements, as is inevitable in the general process of Mappleton 125 ward reduction. Thorpe and Fenny Bentley are not Bradley 265 immediately adjacent but will have Ashbourne as their Thorpe 139 focus for shops & services. Their vicar lives in 2 Fenny Bentley 140 3709 97 1855 Ashbourne. Ashbourne South has been grossly under represented Ashbourne South Ashbourne Hilltop 2808 for several years. The two core parishes are too large Ashbourne St Oswald 2062 to be represented by 2 Cllrs so it must become 3 and Clifton & Compton 422 as a consequence there needs to be an incorporation of Osmaston 122 rural parishes into this new, large ward. All will look Yeldersley 167 to Ashbourne as their source of services. 3 Edlaston & Wyaston 190 5771 353 1924 Norbury Snelston 160 Yeaveley 249 Rodsley 91 This is an expanded ‘exisitng Norbury’ ward. Most Shirley 207 will be dependent on larger settlements for services. Norbury & Roston 241 The enlargement is consistent with the reduction in Marston Montgomery 391 wards from 39 to 34 Cubley 204 Boylestone 161 Hungry Bentley 51 Alkmonton 60 1 Somersal Herbert 71 1886 80 1886 Doveridge & Sudbury Doveridge 1598 This ward is too large for one Cllr but we can see no 1 Sudbury 350 1948 142 1948 simple solution. -

State of Nature in the Peak District What We Know About the Key Habitats and Species of the Peak District

Nature Peak District State of Nature in the Peak District What we know about the key habitats and species of the Peak District Penny Anderson 2016 On behalf of the Local Nature Partnership Contents 1.1 The background .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 The need for a State of Nature Report in the Peak District ............................................................ 6 1.3 Data used ........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 The knowledge gaps ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Background to nature in the Peak District....................................................................................... 8 1.6 Habitats in the Peak District .......................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Outline of the report ...................................................................................................................... 12 2 Moorlands .............................................................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Key points ..................................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Nature and value .......................................................................................................................... -

The Origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 the Avebury Henge Is One of the Famous Mega

1 The origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2Mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 The Avebury henge is one of the famous mega- 7 lithic monuments of the European Neolithic, Research 8 yet much remains unknown about the detail 9 and chronology of its construction. Here, the 10 results of a new geophysical survey and 11 re-examination of earlier excavation records 12 illuminate the earliest beginnings of the 13 monument. The authors suggest that Ave- ’ 14 bury s Southern Inner Circle was constructed 15 to memorialise and monumentalise the site ‘ ’ 16 of a much earlier foundational house. The fi 17 signi cance here resides in the way that traces 18 of dwelling may take on special social and his- 19 torical value, leading to their marking and 20 commemoration through major acts of monu- 21 ment building. 22 23 Keywords: Britain, Avebury, Neolithic, megalithic, memory 24 25 26 Introduction 27 28 Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the 29 Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. ’ 30 Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world s largest stone circle. This in turn encloses — — 31 two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles each approximately 100m in diameter and 32 complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from 33 two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with 34 other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in 35 later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures 36 (Smith 1965; Pollard & Reynolds 2002; Gillings & Pollard 2004). -

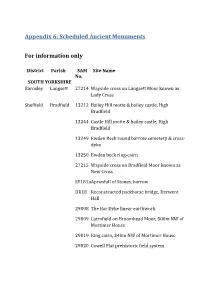

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES; THEIR AGE AND USES. BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D. C. L., F. R. S, V.P.R.A.S., F.R.I.B.A., &c, WITH TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON: ,JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1872. The right of Translation is reserved. PREFACE WHEN, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the ‘Handbook of Architecture,’ one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this ‘Handbook’ as a History of Architecture,’ the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible, the matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed.