Moorland Marathons Philip Brockbank 71

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Froggatt Area

THE FROGGATT AREA THE FROGGATT 1 Grit Staffs Edges Southern Curbar Froggatt Eastern Quarries Valley Burbage Stanage Edges Northern Chew Valley Kinder 2 Bleaklow 3 4 S11 7TY Fox House Inn A6187 Grit Staffs A625 Quarries Area Xxxxxxxx A6187 Longshaw (NT parking p&d) to Xxxxxxx Stanedge Pole B6001 to Xxxxxx B6521 Edges Southern S32 2JA A621 Xxxx Grindleford Station Rd and cafe N XXXX Peacock Inn XXX A625 B6054 XXXX Grouse Inn Curbar XXXXX Froggatt River Xxxxxxx NT car park (p&d) S32 3ZJ M1 Grindleford B6054 XXXXxxx roadside parking XXXXxxx White Gate A621 B6051 XXXXxxx kissing gate Eastern Quarries B6001 0 1km Chequers Inn Froggatt Edge AXXXX AXXXX Valley Stoney Middleton Burbage XXJ XXX XXXJ XXX Froggatt AXXX AXXX Curbar Edge AXX AXX XXX XXX XXXX XXX Moon Inn AX AX Curbar Curbar Gap parking BXXX Calver (p&d) Stanage S32 3YR Bridge Inn main road base Bridge Inn to XXX to XXX B6001 Edges A623 Northern Gardom’s Edge A621 Baslow Chew Birchen Edge Valley minor road base DE45 1PQ Robin Hood Inn (p&d) B6050 Chatsworth Edge A619 Kinder A619 Bleaklow B6012 5 6 FROGGATT EDGE 20 mins Grit OS Grid Ref: SK 249 763 Staffs Altitude: 280m Top-quality gritstone climbing, perhaps only Approach: There are two main approaches, Edges eclipsed by the mighty Stanage. With a rich both from the A625 The most popular ap- Southern diversity of climbing styles and grades, the nu- proach is along the path, which starts from merous classic lines offer an experience among the White Gate (OS Ref. -

New Mills Library: Local History Material (Non-Book) for Reference

NEW MILLS LIBRARY: LOCAL HISTORY MATERIAL (NON-BOOK) FOR REFERENCE. Microfilm All the microfilm is held in New Mills Library, where readers are available. It is advisable to book a reader in advance to ensure one is available. • Newspapers • "Glossop Record", 1859-1871 • "Ashton Reporter"/"High Peak Reporter", 1887-1996 • “Buxton Advertiser", 1999-June 2000 • "Chapel-en-le-Frith, Whaley Bridge, New Mills and Hayfield Advertiser" , June 1877-Sept.1881 • “High Peak Advertiser”, Oct. 1881 - Jul., 1937 • Ordnance Survey Maps, Derbyshire 1880, Derbyshire 1898 • Tithe Commission Apportionment - Beard, Ollersett, Whitle, Thornsett (+map) 1841 • Plans in connection with Railway Bills • Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway 1857 • Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway 1857 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1860 • Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway 1860 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1861 • Midland Railway (Rowsley to Buxton) 1862 • Midland Railway (New Mills widening) 1891 • Midland Railway (Chinley and New Mills widening) 1900 • Midland Railway (New Mills and Heaton Mersey Railway) 1897 • Census Microfilm 1841-1901 (Various local area) • 1992 Edition of the I.G.I. (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Isle of Man, Channel Islands • Church and Chapel Records • New Mills Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1794-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Baptisms 1830-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Burials 1832-1837 • Glossop Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1813-1837 • Hayfield Chapelry and Parish Church Registers • Bethal Chapel, Hayfield, Baptisms 1903-1955 • Brookbottom Methodist Church 1874-1931 • Low Leighton Quaker Meeting House, New Mills • St.Georges Parish Church, New Mills • Index of Burials • Baptisms Jan.1888-Sept.1925 • Burials 1895-1949 • Marriages 1837-1947 • Coal Mining Account Book / New Mills and Bugsworth District 1711-1757 • Derbyshire Directories, 1808 - 1977 (New Mills entries are also available separately). -

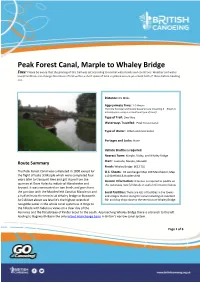

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 6½ Miles. Approximate Time: 1-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: One Way Waterways Travelled: Peak Forest Canal Type of Water: Urban and rural canal. Portages and Locks: None Vehicle Shuttle is required Nearest Town: Marple, Disley, and Whaley Bridge Route Summary Start: Lockside, Marple, SK6 6BN Finish: Whaley Bridge SK23 7LS The Peak Forest Canal was completed in 1800 except for O.S. Sheets: OS Landranger Map 109 Manchester, Map the flight of locks at Marple which were completed four 110 Sheffield & Huddersfield. years later to transport lime and grit stone from the Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle on quarries at Dove Holes to industrial Manchester and this waterway. See full details in useful information below. beyond. It was constructed on two levels and goes from the junction with the Macclesfield Canal at Marple six and Local Facilities: There are lots of facilities in the towns a-half-miles to the termini at Whaley Bridge or Buxworth. and villages that lie along the canal including an excellent At 518 feet above sea level it’s the highest stretch of fish and chip shop close to the terminus at Whaley Bridge. -

State of Nature in the Peak District What We Know About the Key Habitats and Species of the Peak District

Nature Peak District State of Nature in the Peak District What we know about the key habitats and species of the Peak District Penny Anderson 2016 On behalf of the Local Nature Partnership Contents 1.1 The background .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 The need for a State of Nature Report in the Peak District ............................................................ 6 1.3 Data used ........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 The knowledge gaps ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Background to nature in the Peak District....................................................................................... 8 1.6 Habitats in the Peak District .......................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Outline of the report ...................................................................................................................... 12 2 Moorlands .............................................................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Key points ..................................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Nature and value .......................................................................................................................... -

Edale: a Study of a Pennine Dale

Scottish Geographical Magazine ISSN: 0036-9225 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsgj19 Edale: A study of a Pennine Dale C. B. Fawcett B.Litt., M.Sc. To cite this article: C. B. Fawcett B.Litt., M.Sc. (1917) Edale: A study of a Pennine Dale , Scottish Geographical Magazine, 33:1, 12-25, DOI: 10.1080/00369221708734256 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00369221708734256 Published online: 28 Jun 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 27 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsgj20 Download by: [University of California Santa Barbara] Date: 18 June 2016, At: 02:09 12 SCOTTISH GEOGRAPHICAL MAGAZINE. EDALE: A STUDY OF A PENNINE DALE.1 By C. B. FAWCETT, B.Litt., M.Sc. (With Sketch-Map and Figures.) THE dale marked on the large-scale maps of the High Peak District as the "Vale of Edale" is the high-lying valley along the south- eastern side of the Peak. From the heights above Dalehead to Edale End the valley stretches for nearly five miles in a line from west-south- west to east-north-east. In its widest parts the breadth from crest to crest reaches three miles ; but most of this is moorland, and the width of the habitable portion nowhere exceeds one mile, and averages little more than half that distance. The total area of the civil parish of Edale is eleven square miles, of which the greater part is uncultivated and uninhabited moorland. -

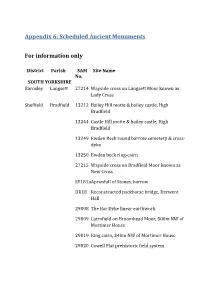

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley

High Peak and Hope Valley January – April 2020 Community Rail Partnership Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley Welcome to this guide It contains details of Guided Walks and Folk Trains on the Hope Valley, Buxton and Glossop railway lines. These railway lines give easy access to the beautiful Peak District. Whether you fancy a great escape to the hills, or a night of musical entertainment, let the train take the strain so you can concentrate on enjoying yourself. High Peak and Hope Valley This leaflet is produced by the High Peak and Hope Valley Community Rail Partnership. Community Rail Partnership Telephone: 01629 538093 Email: [email protected] Telephone bookings for guided walks: 07590 839421 Line Information The Hope Valley Line The Buxton Line The Glossop Line Station to Station Guided Walks These Station to Station Guided Walks are organised by a non-profit group called Transpeak Walks. Everyone is welcome to join these walks. Please check out which walks are most suitable for you. Under 16s must be accompanied by an adult. It is essential to have strong footwear, appropriate clothing, and a packed lunch. Dogs on a short leash are allowed at the discretion of the walk leader. Please book your place well in advance. All walks are subject to change. Please check nearer the date. For each Saturday walk, bookings must be made by 12:00 midday on the Friday before. For more information or to book, please call 07590 839421 or book online at: www.transpeakwalks.co.uk/p/book.html Grades of walk There are three grades of walk to suit different levels of fitness: Easy Walks Are designed for families and the occasional countryside walker. -

Derbyshire Gritstone Way

A Walker's Guide By Steve Burton Max Maughan Ian Quarrington TT HHEE DDEE RRBB YYSS HHII RREE GGRRII TTSS TTOONNEE WW AAYY A Walker's Guide By Steve Burton Max Maughan Ian Quarrington (Members of the Derby Group of the Ramblers' Association) The Derbyshire Gritstone Way First published by Thornhill Press, 24 Moorend Road Cheltenham Copyright Derby Group Ramblers, 1980 ISBN 0 904110 88 5 The maps are based upon the relevant Ordnance Survey Maps with the permission of the controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Crown Copyright reserved CONTENTS Foreward.............................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 6 Derby - Breadsall................................................................................................................. 8 Breadsall - Eaton Park Wood............................................................................................ 13 Eaton Park Wood - Milford............................................................................................... 14 Milford - Belper................................................................................................................ 16 Belper - Ridgeway............................................................................................................. 18 Ridgeway - Whatstandwell.............................................................................................. -

NOTICE of POLL and SITUATION of POLLING STATIONS Election of A

NOTICE OF POLL and SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS High Peak Borough Council Election of a Derbyshire County Councillor for Chapel & Hope Valley Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Chapel & Hope Valley Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BANN 31 Beresford Road, Independent Barton Sarah L(+) Barton Michael(++) Paddy Chapel-en-le-Frith, High Peak, SK23 0NY COLLINS 9 Hope Road, The Green Party Wight Jeremy P(+) Farrell Charlotte N(++) Joanna Wiehe Edale, Hope Valley, S33 7ZF GOURLAY Ashworth House, The Conservative and Sizeland Kathleen(+) Gourlay Sara M(++) Nigel Wetters Long Lane, Unionist Party Chapel-en-le-Frith, High Peak, SK23 0TF HARRISON Castleton Hall, Labour Party Cowley Jessica H(+) Borland Paul J(++) Phil Castle Street, Castleton, Hope Valley, S33 8WG PATTERSON (Address in High Peak) Liberal Democrats Rayworth Jayne H(+) Foreshew-Cain James Robert Stephen J(++) 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled -

THE STATUS of GOLDEN PLOVERS in the PEAK PARK, ENGLAND in RELATION to ACCESS and RECREATIONAL DISTURBANCE by D.W.Yalden

3d THE STATUS OF GOLDEN PLOVERS IN THE PEAK PARK, ENGLAND IN RELATION TO ACCESS AND RECREATIONAL DISTURBANCE by D.W.Yalden A survey of all Peak Park moorlands in 1970-75 concerned birds which had moved onto the then located approximately 580-d00 pairs of Golden recent fire site of Totside Moss - I recorded Plovers (P•u•$ •pr•c•r•); on the present only 2 pairs in those 1-km squares, where they county boundaries around half of these are in found 11 pairs. Also the S.E. Cheshire Derbyshire, a few in Cheshire, Staffordshire moorlands have recently been thoroughly studied and Lancashire (16, 6 and 2 pairs, during the preparation of a breeding bird atlas respectively), and the rest in Yorkshire for the county. Where I found 15 pairs in (Yalden 1974). There are very sparse 1970-75, there seem to be only eight pairs now populations of Golden Plovers in S.W. Britain (A. Booth, D.W. Yalden pets. ohs.). and Wales. On Dartmoor, an R.S.P.B. survey found only 14 pairs, and in the national The Pennine Way long distance footpath runs breeding bird survey this species was only along the ridge from Snake Summit south to recorded in 50 (10 km) squares in Wales, (Mudge Mill-Hill and consequently this area has been et a•. 1981, Shatrock 1976): the total Welsh subjected to disturbance from hill-walkers. population was estimated at 600 pairs. Further Here the Golden Plover population has been north in the Pennines, and in Scotland, tensused annually since 1972. The population populations are larger. -

257 X57 Valid From: 05 September 2021

Bus service(s) 257 X57 Valid from: 05 September 2021 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Crosspool The Moor Market Rivelin Dams Bamford (257) Sheffield Childrens Hospital Eyam (257) Derwent Reservoir (X57) Baslow (257) Ladybower Reservoir Bakewell (257) Manchester Airport (X57) Derwent (X57) Manchester (X57) Manchester Airport (X57) What’s changed Service 257 - No changes. Service X57 - Changes to the times of some journeys. Buses will also serve Hyde (Bus Station). Operator(s) Hulleys of Baslow How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 257 and X57 ! ! ! 17/12/2020# ! ! ! Derwent, Access Rd/Fairholmes Sheeld, Western Bank/ X57 continues to Glossop, 257, X57 ! Sheeld University ! Manchester, Coach Station Crosspool, !! and Manchester Airport Manchester Rd/Benty Ln ! !! ! Waverley X57 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 257 X57 ! ! X57 ! !! !! Sheeld, Interchange ! ! Ashopton, A57/Ladybower Inn !! Ashopton, Derwent Lane/Viaduct Crosspool, Mancheter Road/Vernon Terrace !! !! ! !! Hope Yorkshire Bridge, Ashopton Rd/Yorkshire Bridge Hotel ! Woodhouse Barber Booth 257 Gleadless! ! Hope, Castleton Rd/College ! ! ! ! Birley ! ! ! ! Bamford, Sickleholme/Bus Turnaround ! Norton Bradwell, Stretfield Road/Batham Gate Hathersage, Station Rd/Little John ! Mosborough Sparrowpit Operates via Lowedges Bradwell at 0850/1525 Peak Forest and Totley Marsh Lane Hope Valley College at 257 0845/1535 257 West Handley Grindleford, Main Rd/Mount Pleasant Great Hucklow, Foolow Road/Grindlow Lane -

Our Edale Meeting Point, Peak District

Our Edale Meeting Point, Peak District Don’t leave home without these instructions Please use the following details to arrive at the meeting point 15 minutes prior to your course start time to enable us to make a prompt start. While the course is held in a rural location the nearby cities of Manchester and Sheffield, and the surrounding motorways can cause significant traffic congestion at times so please allow plenty of time for your journey. Setting Our navigation course takes place within the stunning Peak District National Park and we use the Kinder Scout area as our training ground. Set in the beautiful hills of Derbyshire there is no better venue to learn Navigation. Our starting point is a short walk from the centre of Edale village. Participants have the option of booking into one of many local B&B’s or joining the instructors at Coopers camping and caravan site. Running late? If you are delayed at all please contact us at the earliest possible moment on 07843064114 so we can try and plan logistically to get an instructor back to the meeting point. However, please note due to the rural setting there is no phone signal in Edale so if it is the morning of the course we will not be able to assist you so a late arrival may mean that we cannot wait for you at the meeting point and you may not be able to take part in the course – In these situations late arrivals will be considered a cancellation on your part. On arrival On the first morning of your 2 day course you will be met by a Woodland Ways instructor at 09:30 outside the Old Nags Head pub, S33 7ZD which is in the centre of Edale village.