The Tower of Babel: Archaeology, History and Cuneiform Texts1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

1. Mesopotamia A

Table of Contents : 1. Mesopotamia a. Introduction 1-1 (General introduction to Mesopotamia, its geography, topography, civilization, and commerce) b. The Early Dynastic Period: Sumer (to 2316) i. Introduction 1-4 (The discovery of Sumer, cuneiform writing, religion, the ziggurats, art) ii. Sumerian Philosophy and Religion 1-8 (The Sumerian worldview, cosmology, major deities, religious philosophy and practice) iii. Sumerian Mythology 1-12 (Major mythological characters, Sumerian “paradise,” similarities and differences with the biblical accounts) iv. Mesopotamian Creation Stories 1-14 (Sumerian creation accounts, Enuma Elish, comparison to biblical account of creation) v. Gilgamesh and The Great Flood 1-16 (The major Gilgamesh myths, The Epic of Gilgamesh, discovery of the epic, comparison to biblical account of the flood) vi. The End of the Early Dynastic Period 1-18 (Loss of leadership, invasion of the Amorites) c. The Second Dynasty: Akkadian (2334 – 2193) i. Introduction 1-19 (Creation of empire in single ruler) ii. Sargon the Great 1-20 (Birth and early years, ascension, importance in unifying Sumerian world) iii. Rimush 1-21 iv. Manishtusu 1-22 v. Naram-Sin 1-22 (His general greatness and fall) vi. Shar-kali-sharri 1-23 vii. Gudea 1-23 (The invasion of the Gutians, investment in Lagash) viii. Utu-hegal 1-24 d. The Third Dynasty: Ur (2112 – 2004) i. Ur-Nammu 1-24 (Brilliance, military conquests, the ziggurats, their meaning and probable connection with the Tower of Babel) ii. Shulgi 1-26 iii. Aram-Sin 1-26 iv. Shu-Sin 1-26 v. Ibbi-Sin 1-27 (Reasons for loss of power, defeat to the Elamites, beginning of intermediate period, king lists) e. -

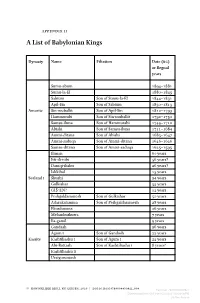

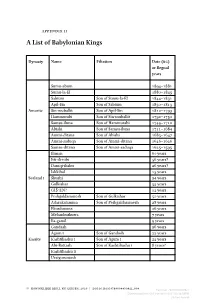

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets, &C., in the British

CUNEIFORM TEXTS FROM BABYLONIAN TABLETS IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM PART XLV OLD-BABYLONIAN BUSINESS DOCUMENTS BY TH. G. PINCHES PUBLISHED BY THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM LONDON 1964 © 1964 The Trustees of the British Museum Printed by Her Majesty's Stationery Office PREFACE All but one of the 122 texts published here are Old-Babylonian business, administrative, and legal documents. The single exception (No. 122) is apparently an Old-Babylonian incantation. As forecast in the Preface to Cuneiform Texts XLIV, the present volume makes available to students the remainder of the unpublished Pinches copies from the two 'Budge Collections,' Bu.88-5-12 and Bu.91-5-9, to accommodate which the traditional number of fifty plates has exceptionally been increased to fifty-four. Over one half of the texts are dated or can be assigned to a ruler and these have been arranged chronologically by reigns in the following order: first, the tablets bearing date-formulae; then, those mentioning the king in the oath-formula; finally, those men- tioning the king in the legend of a seal. No. 71, a tag of Samsu-Iluna, year 2, has, however, been grouped with other, undated tags on'plate XXXIII. The arrangement of the undated tablets (pls. XXXIV-LIV) has been determined by the needs of plate-setting. The reigns represented in our documents are: Bun-tah 'un-Ila of Sippar (No. 1; this is the envelope, with a slightly variant text, of the tablet published by Waterman, Business Documents, No. 33); Sumu-la-El (No. 2); Sabium (Nos. 3-5); Apil-Sin (Nos.6- 12); Sin-muballit (Nos. -

Mesopotamian Year Names

Mesopotamian Year Names Neo-Sumerian and Old Babylonian Date Formulae prepared by Marcel Sigrist and Peter Damerow LIST OF KINGS The list of more than 2,000 year names which is made accessible here has been compiled as a tool for the dating of cuneiform tablets as well as for supporting historical studies on early bookkeeping techniques. This tool essentially consists of a collection of date formulae in administrative documents as they were used by the scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, and of computer generated indices for a quick identification of incomplete date formulae on damaged cuneiform tablets and of issues and events mentioned in these formulae. The collection covers presently the time period ● from the time of the empire of Sargon ● to the end of the dynasty of Babylon. Access is provided through ● a list of cities and kings, ● a list of words, ● a list of words of the English translation. According to the pupose of this compilation the data formulae as they are presented here do not quote specific texts but are often composite formulae based on several sources. Furthermore it was impossible to give always the numerous variants of some of the year names. In cases of doubt whether the given version adequately represents the textual evidence users should consult the references and the relevant publications on Mesopotamian year names. (A bibliography is currently in preparation and will soon be accessible here.) History of the project The preparation of this electronic tool is an outcome of an unusual and long-lasting cooperation between an assyiologist and an historian of science at intervals over a period of more than 10 years. -

Studies in Old Babylonian History

PIHANS • XL Studies in Old Babylonian History by Marten Stol Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul 1976 UITGA YEN VAN HET NEDERLANDS HISTORISCH-ARCHAEOLOGISCH INSTITUUT TE lSTANBUL Publications de l'Institut historique et archeologique neerlandais de Stamboul sous la direction de E. VAN DONZEL, Pauline H. E. DONCEEL-VOUTE, A. A. KAMPMAN et Machteld J. MELLINK XL STUDIES IN OLD BABYLONIAN HISTORY STUDIES IN OLD BABYLONIAN HISTORY by MARTEN STOL NEDERLANDS HISTORISCH-ARCHAEOLOGISCH INSTITUUT TE !STANBUL 1976 Copyright 1976 by Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Noordeindsplein 4-6, Leiden All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form I.S.B.N. 90 6258 040 8 Printed in Belgium CONTENTS page PREFACE . IX l. A DATE LIST CONTAINING YEAR NAMES OF WARAD-SIN AND RIM-SIN 1 1. The date list . 2. The year names of Warad-Sin 6 3. The year names of Rim-Sin . 18 4. The year names of Sin-iqi:Sam 23 5. Sabium of Baby1on in Southern Babylonia 27 6. Synchronisms of Gungunum and kings of Isin 29 7. Bur-Sin and Sumu-el . 30 Il. UNIDENTIFIED YEAR NAMES OF HAMMURABI 32 Ill. RIM-SIN Il . 44 1. The ninth year of Samsu-iluna 44 2. Two archives . 45 3. Evidence from other texts 47 4. Intercalary months and the calendar 48 5. The defeat of Rim-Sin II 50 6. The events of Samsu-iluna year 10 52 7. Rim-Sin II, years (a) and (b) 53 8. The aftermath 55 Appendixes 56 IV. -

Mesopotamian Political History Into Distinct Halves. Thus the Old Baby

FOR FURTHER READING 109 Mesopotamian political history into distinct halves. Thus the Old Baby- lonian world is deeply rooted in the third millennium, while Kassite culture is more akin to the first. Potts, Daniel T. Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1997. A useful collection of stand-alone essays covering features of Mesopotamian civilization often overlooked in other studies. Gives much attention to the written cuneiform sources while also updating and interacting with the perti- nent secondary literature. Roaf, Michael. Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. New York: Facts on File, 1996. The best available atlas on ancient Mesopotamia. Also includes much discussion and treatment of relevant background information. Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. 3rd ed. London: Penguin, 1992. Written by a French medical doctor who subsequently became a scholar of ancient Mesopotamia in his own right and published articles in technical jour- nals. A comprehensive survey with an astounding sweep from Paleolithic times to the Sassanians (224–651 C.E.), this book is engag- ingly written and lucid. Its usefulness is still evident in its third edition since its original publication in 1964. Saggs, H. W. F. The Greatness That Was Babylon: A Survey of the Ancient Civilization of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. 2nd ed. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1988. Originally published in 1962, this authoritative and comprehensive treatment covers Babylonian society, law and adminis- tration, trade and economics, religion, literature, and science, as well as providing an overview of political history. Abbreviated and more up-to-date treatment may be found in the author’s Babylonians (Berke- ley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000). -

Mesopotamian History and Environment Memoirs

oi.uchicago.edu MESOPOTAMIAN HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT SERIES II MEMOIRS oi.uchicago.edu MESOPOTAMIAN HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT Editors: L. De Meyer and H. Gasche SERIES II MEMOIRS Advisory Board: J.A. Armstrong (Cambridge MA), C. Bonnet (Geneva), P. Buringh (Wageningen), D. Charpin (Paris), M. Civil (Chicago), S.W. Cole (Helsinki), McG. Gibson (Chicago), B. Hrouda (Miinchen), J.-L. Huot (Paris), J.N. Postgate (Cambridge UK), M.-J. Steve (Nice), M. Tanret (Ghent), F. Vallat (Paris), and K. Van Lerberghe (Leuven). Communications for the editors should be addressed to : MESOPOTAMIAN HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT University of Ghent Sint-Pietersplein 6 B-9000 GHENT Belgium oi.uchicago.edu MESOPOT AMI AN HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENT SERIES II MEMOIRS IV DATING THE FALL OF BABYLON A REAPPRAISAL OF SECOND-MILLENNIUM CHRONOLOGY (A JOINT GHENT-CHICAGO-HARVARD PROJECT) by H. GASCHE, J.A. ARMSTRONG, S.W. COLE and V.G. GURZADYAN Published by the University of Ghent and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1998 oi.uchicago.edu Abbreviation of this volume : MHEM IV © University of Ghent and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago D/1998/0634/1 (Belgium) ISBN 1-885923-10-4 (USA) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-84354 Printed in Belgium The fonts used are based on Cun6iTyp 1 designed by D. Charpin. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or translated in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, microfiche or any other means without written permission from the publishers. This volume presents research results of an 'Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Programme - Belgian State, Prime Minister's Office - Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs.' oi.uchicago.edu CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CHAPTER 1 : PRESENT SOURCES FOR THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE SECOND MILLENNIUM 5 1.1. -

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody 1333 Kurigalzu II Son of Burnaburiash II 1332–1308 Nazimaruttash Son of Kurigalzu II 1307–1282 Kadashman-Turgu Son of Nazimaruttash 1281–1264 Kadashman-Enlil II Son of Kadashman-Turgu 1263–1255 Kudur-Enlil Son of Kadashman-Enlil II 1254–1246 Shagarakti-Shuriash Son of Kudur-Enlil 1245–1233 Kashtiliashu IV Son of Shagarakti-Shuriash 1232–1225 Enlil-nadin-shumi 1224 Kadashman-Harbe II 1223 Adad-shuma-iddina 1222–1217 Adad-shuma-usur Son of Kashtiliashu IV? 1216–1187 Meli-Shipak Son of Adad-shuma-usur 1186–1172 Merodach-Baladan I Son of Meli-Shipak 1171–1159 Zababa-shuma-iddina 1158 Enlil-nadin-ahhe 1157–1155. -

Appendix to Chapter 5

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/25842 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Boer, Rients de Title: Amorites in the Early Old Babylonian Period Issue Date: 2014-05-28 Year Babylon Sippar Kiš Damrum/Kiš’vicinity Marad Isin Larsa Kisurra Uruk Ešnunna Aššur Tutub Nêrebtum Šaduppûm Uzarlulu Šadlaš Diniktum Dēr Malgium Šimaški & Other/Remarks Sukkalmah 2004 Išbi-Erra 15 Yamṣium 1 ≈Kirikiri 2003 Išbi-Erra 16 2002 Išbi-Erra 17 Kindadu Fall or Ur at the hand of Šimaški/Elam 2001 Išbi-Erra 18 2000 Išbi-Erra 19 Idadu I 1999 Išbi-Erra 20 1998 Išbi-Erra 21 ≈Puzur-Aššur I 1997 Išbi-Erra 22 1996 Išbi-Erra 23 1995 Išbi-Erra 24 ≈Bilalama ≈Ilum- ≈Šu-Kakka ≈Tan-ruhuratir II mutabbil 1994 Išbi-Erra 25 1993 Išbi-Erra 26 1992 Išbi-Erra 27 ≈ Šalim-ahum From here on: sukkalmah dynasty 1991 Išbi-Erra 28 1990 Išbi-Erra 29 1989 Išbi-Erra 30 1988 Išbi-Erra 31 1987 Išbi-Erra 32 1986 Šu-Ilīšu 1 1985 Šu-Ilīšu 2 1984 Šu-Ilīšu 3 ≈Ilušuma 1983 Šu-Ilīšu 4 1982 Šu-Ilīšu 5 1981 Šu-Ilīšu 6 1980 Šu-Ilīšu 7 1979 Šu-Ilīšu 8 1978 Šu-Ilīšu 9 ≈Nidnūša ? ≈Nabi- 1977 Šu-Ilīšu 10 Enlil 1976 Iddin-Dagan 1 Samium 1 1975 ≈Išar-ramašu ≈Ebarat II 1974 1973 1972 Šu-Ištar 1 King: Erišum I 1971 Šukkutum 1970 Iddin-ilum 1969 Šu-Anum 1968 Inah-ilī 5 ≈Silhaha 1967 Suetaya 1966 Daya 1965 Ilī-ellitī ≈Temti-Agun I 1964 Šamaš-ṭāb 1963 Agusa 10 1962 Idnaya 1961 Quqādum 1960 Puzur-Ištar ≈Šu- 1959 Lā-qēpum Amurru ≈Pala-iššan 1958 Šu-Laban 15 1957 Šu-Bēlum 1956 Nabi-Sîn 1955 Išme-Dagan 1 Hadaya 1954 Ennam-Aššur 1953 Ikūnum 20 ≈Iram-x- 1952 ≈Uṣur-awassu -

Appendix II a List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 02:16:59PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody