Narrative, Image, and Technology in Twentieth-Century Literature By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

Adelaidean Volume 17 Number 10 December 2008

FREE Publication December 2008 | Volume 17 | Number 10 inside this issue 8 Cricket ball Family unit set in Stone Age quality takes a knock 10 South Australian Engineering of the Year Awards A study by a University of Adelaide sports engineer shows that not all cricket balls are consistently manufactured, causing quality issues and potentially having major 15 implications for cricket matches. Creative writing student The research, conducted by wins literary prize the coordinator of the Sports Engineering degree program at the University of Adelaide, Associate Professor Franz Konstantin Fuss, studied fi ve models of cricket balls manufactured in Australia, India and 17 Pakistan. The study looked at the methods Penguins’ not-so-happy of construction, stiffness, viscous ending discovered in DNA and elastic properties, and included changes to the balls’ performance under compression and stress relaxation tests. Dr Fuss found that the model manufactured in Australia – the Kookaburra Special Test – was the only cricket ball manufactured consistently. The other four models were found to have inconsistent “stiffness”, which can play an important part in how a ball reacts when struck by the bat. “In contrast to other sport balls, most cricket balls are still hand-made, which may affect the consistency of manufacturing and thus the properties of a ball,” Dr Fuss said. story continued on page 18 Adelaidean Adelaidean is the offi cial newspaper of the University of Adelaide. It provides news and information about the University to the general public, with a focus on Life Impact. Circulation: 11,000 per month From the Vice-Chancellor (March to December) Online readership: 90,000 hits per month (on average) www.adelaide.edu.au/adelaidean Editor: The world is defi nitely getting smaller. -

Resume of Verena

VERENA TAY ~ FULL RESUME ~ [email protected] | http://verenatay.com | +65 91263835 [email protected] | http://www.moonshadowstories.com MA in English Literature (National University of Singapore, 1993) MA in Voice Studies (Central School of Speech and Drama, London, 2005) MFA in Creative Writing (Fiction) (City University of Hong Kong, 2015) —————————————————————————————————— For more than 25 years, Verena Tay acted, directed and written for local English-language theatre in Singapore. To date, three collections of her plays have been published: In the Company of Women (SNP Editions, 2004), In the Company of Heroes and Victimology (both by Math Paper Press, 2011). An Honorary Fellow at the International Writing Program, University of Iowa (Aug–Nov 2007), she now writes and edits fiction and conducts the occasional creative writing workshop. Spectre: Stories from Dark to Light (Math Paper Press, 2012) is her first collection of short stories. During 2012 and 2013, she also compiled and edited four other short story anthologies: Balik Kampung, Balik Kampung 2A: People and Places and Balik Kampung 2B: Contemplations (Math Paper Press) and A Monsoon Feast (DFP Productions/Monsoon Books). In addition, Verena brings stories vocally and physically alive in her unique fashion. She chooses her storytelling repertoire carefully, adapting folktales with strong characters or creating original tales with a twist. Where possible, she invests her quirky brand of humour, especially in her stories for adults, to delight and encourage her audience to appreciate a different perspective on life. Together with Kamini Ramachandran with whom she founded MoonShadow Stories in November 2004, Verena has been telling stories at various community venues across Singapore, much to the delight and enjoyment of adults and children. -

Download the File

DECONSTRUCTING POSTCOLONIAL MEMORY THROUGH FILIPINO AMERICAN LITERATURE At> 3<^ XoIf A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University E.W&L In partial fulfillment of •ASif the requirements for the Degree Master of English In Literature by Lisa Ang San Francisco, California Fall 2015 Copyright by Lisa Ang 2015 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Deconstructing Postcolonial Memory Through Filipino American Literature by Lisa Ang, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of English in Literature at San Francisco State University. Gitanjali Shahani, Ph.D. Associate Professor Wai-Leung Kwok, Ph.D. Associate Professor DECONSTRUCTING POSTCOLONIAL MEMORY THROUGH FILIPINO AMERICAN LITERATURE Lisa Ang San Francisco, California 2015 This thesis argues that Filipino American literature can be viewed as postcolonial literature when viewed in relation to history and memory. It acknowledges the difficulties that lay waiting for a postcolonial analysis in general and moves past these potential complications with an understanding of the usefulness of this categorization for two unique examples of Filipino American literature today. By understanding subaltemity in Miguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado and Tess Uriza Holthe’s When the Elephants Dance, this thesis traces remnants of the past back to the simultaneously possible and impossible nature of constructing a national story of the Philippines. I certify that the Choose an item, is a correct representation of the content of this Choose an item Chair, Thesis Committee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family, especially my parents, William and Adelaida Ang, who have always encouraged and supported my growth as a learner and student. -

Straus Literary 319 Lafayette Street, Suite 220 New York, New York 10012 P 646.843.9950 ⎪ F 646.390.3320 Www

Straus Literary 319 Lafayette Street, Suite 220 New York, New York 10012 p 646.843.9950 ⎪ f 646.390.3320 www. strausliterary.com Agent: Jonah Straus [email protected] Foreign Rights on Offer – Frankfurt Book Fair 2016 FICTION Face Blind Lance Hawvermale • NORTH AMERICA– MINOTAUR BOOKS / ST. MARTIN’S PRESS (AUGUST 2016) An atmospheric and tightly wound thriller set in the otherworldly landscape of Chile's Atacama Desert, the driest and most desolate place on earth, where not a drop of rain has fallen for over four hundred years. An American astronomer posted to an observatory there with a strange condition called face blindness witnesses a murder but cannot identify the perpetrator. As a result he and three other social misfits are thrown together to face a series of chilling violent episodes and unearth dark secrets from Chile's fascist past. “Deftly written, full of appealing characters and moments that sparkle with tenderness.” —Publishers Weekly (review of Seeing Pink) “A fast-paced, witty mystery with wonderful multilayered characters and a whopper of a climax.” —Johnny Quarles, bestselling author of Fool’s Gold (Avon) Counternarratives John Keene Winner of the Whiting Award • WORLD ENGLISH – NEW DIRECTIONS PUBLISHING (MAY 2015) • FRENCH – ÉDITIONS CAMBOURAKIS • TURKISH—ALAKARGA Twenty years after his debut, John Keene returns with a brilliant novella and story collection. Conjuring slavery and witchcraft, and with bewitching powers all its own, Counternarratives continually spins history—and storytelling—on its head. Ranging from the 17th century to the present and crossing multiple continents, the novellas and stories draw upon memoirs, newspaper accounts, detective stories, interrogation transcripts, and speculative fiction to create new and strange perspectives on our past and present. -

For Whom Are Southeast Asian Studies?

72 For Whom Are Southeast Asian Studies? Caroline S. HAU Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University Which audiences, publics, and peoples do Southeast Asianists address and serve? The question of “audience(s)”—real and imagined, intended and unintended—is arguably central to (re)conceptualizing the rationale, scope, efficacy, and limits of Southeast Asian Studies. It has an important bearing on what kind of topics are chosen for study, what and how personal and institutional networks and intellectual exchanges are mobilized, which dialogues and collaborations are initiated, in what language(s) one writes in, where one publishes or works, which arenas one intervenes in, and how the region is imagined and realized. After surveying the recent literature on Southeast Asian Studies, I focus on Jose Rizal’s two novels—Noli me tangere (1887)and El filibusterismo (1891)—and Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities (1983, 1991, 2006) and examine the ways in which the issue of audience(s) crucially informed the intellectual projects of the two authors, and how the vicissitudes of production, circulation, translation, and reception shaped the intellectual, political, and artistic trajectories and legacies of these three notable Southeast Asian studies texts. I will also discuss the power of these texts to conjure and call forth unexpected and unintended audiences that have the potential to galvanize Southeast Asian studies while stressing the connected histories that link Southeast Asia to other regions and the world. Keywords: Southeast Asia, area studies, nationalism, Benedict Anderson, José Rizal ASIAN STUDIES: Journal 59of Critical Perspectives on Asia For Whom Are Southeast Asian Studies? 7360 Introduction The best career advice I ever received came out of my B exam, the oral defense of my dissertation, twenty-two years ago at Cornell University. -

Literature and Democratic Criticism: the Post-9/11 Novel and the Public Sphere

Literature and Democratic Criticism: The Post-9/11 Novel and the Public Sphere Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von Maria Diaconu April 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dietmar Schloss Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Günter Leypoldt Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 9/11 in Intellectual Debates ................................................................................................... 2 Liberal Humanism(s) .............................................................................................................. 6 The Post-9/11 Novel ............................................................................................................. 12 Chapter 1: Irony Is Dead, Long Live Irony: Satire after 9/11 ............................................................. 21 The Unbearable Triviality of Being: David Foster Wallace’s The Suffering Channel and Claire Messud’s The Emperor’s Children as September 10 Satires .................................... 34 A 9/12 Satire: Jess Walter’s The Zero .................................................................................. 48 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 57 Chapter 2: Playing the Victim: The Politics of Memorialization and Grief ........................................ 59 Sentimental -

Extrajudicial Killings and Human Rights Education in the Philippines

ALEXANDER AGNELLO ・ Volume 5 n° 6 ・ Spring 2017 Extrajudicial Killings and Human Rights Education in the Philippines International Human Rights Internships Program - Working Paper Series About the Working Paper Series The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). Through the program, students complete placements with NGOs, government institutions, and tribunals where they gain practical work experience in human rights investigation, monitoring, and reporting. Students then write a research paper, supported by a peer review process, while participating in a seminar that critically engages with human rights discourses. In accordance with McGill University’s Charter of Students’ Rights, students in this course have the right to submit in English or in French any written work that is to be graded. Therefore, papers in this series may be published in either language. The papers in this series are distributed free of charge and are available in PDF format on the CHRLP’s website. Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. The opinions expressed in these papers remain solely those of the author(s). They should not be attributed to the CHRLP or McGill University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). 1 Abstract Extrajudicial killings in the Philippines have been denounced by the international community as a clear derogation from the rule of law. However, that statement by itself does not tell us which aspects of the rule of law are being corroded by the commission of extrajudicial killings. -

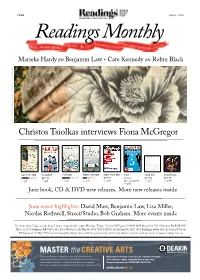

Christos Tsiolkas Interviews Fiona Mcgregor

FREE JUNE 2010 Readings Monthly Marieke Hardy on Benjamin Law • Cate Kennedy on Robin Black OURTESY SCRIBE PUBLICATIONS) C ( INDELIBLE INK OR'S G DETAIL OF COVER FIONA MGRE DETAIL Christos Tsiolkas interviews Fiona McGregor AUS FICTION HUMOUR FICTION NON-FICTION NON-FICTION DVD JAZZ CD CLASSICAL $32.95 $27.95 $27.95 $32.95 $27.95 $55 $39.95 $19.95 $34.95 $32.95 $34.95 >> p5 >> p4 >> p6 >> p11 >> p10 Blu-ray $44.99 >> p17 >> p19 >> p16 June book, CD & DVD new releases. More new releases inside June event highlights : David Marr, Benjamin Law, Lisa Miller, Nicolas Rothwell, Street/Studio, Bob Graham. More events inside All shops open 7 days, except State Library shop, which is open Monday - Friday. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952. Port Melbourne 253 Bay St 9681 9255 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 email [email protected] Check opening hours, find event details, or browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au 2 Readings Monthly June 2010 From the Editor JUNE HIGHLIGHTS ThisTHE READINGS Month’sBLOOMSDAY News NEW LITERARY T-SHIRTS I’m excited about this issue (if FOUNDATION Bloomsday in Melbourne’s seventeenth COMING SOON IN JUNE I say so myself) – and by Applications for the Readings Foundation celebration, on Wednesday 16 June 2010, Celebrating the world's some fantastic June titles. will open in August, 2010. The Foundation focuses on the Circe chapter of James Joyce’s greatest stories through Fiona McGregor’s clever, aims to increase and formalise Readings’ Ulysses. -

Philippines Travel Guide 2014-2015

Unitarian Universalist Partner Church Council Philippines Travel Tips and Information 201 4–2015 What to Pack • Passport • Travel journal (you will receive this from the UUPCC after registration) • Paper copy of passport main page • List of important contact numbers • Credit card/debit card (authorized for foreign use) • Electrical converter (they are on 220) if needed • Your medications • Small first aid kit with antihistamines, antibiotic creams, bandaids, pain relievers, antidiarrheal drugs and constipation relievers • Insect repellent • Camera with extra film/memory card/battery charger • Good walking shoes—two pair in case of soaking • Lightweight raincoat or poncho/umbrella • Lightweight slacks • Tops with sleeves • Socks • Lightweight jacket • Swim suit/shorts/t-shirt for swimming • Travel towel/small washcloth in Ziploc bag • Toiletries • Small tissue packets/TP • Little packets of alcohol wipes and antibacterial hand sanitizer • Sunscreen • Sunglasses/extra pair of glasses • A little laundry soap • Earplugs/sleep mask if helpful for sleeping; other sleep aids if desired • Quart size Ziploc bags (for carry on and misc. duties) • Pictures of your home congregation/community • Gifts • Laptop computer, if you wish Most important… a good, go-with-the-flow attitude. This trip is physically demanding. There can be strenuous walks to visit congregations. If you have a medical condition, please consult with your doctor before considering this trip. Contents You will find in this little booklet, some tips, information, and wisdom about pilgrimage to the Philippines. This has been gathered over the years by travelers and trip leaders, and com - piled here for your reading pleasure. What to Pack .......................................... inside front cover Background Information ............................................. -

CV Syjuco 2018

MIGUEL SYJUCO NYU Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE ● +971 52 501 2144 ● [email protected] STUDIES & RESEARCH: Fortifying Democracy Project/Usapang ATIN (June 2018 - present) New York University Abu Dhabi, UAE Developing an initiative to create scalable models for autonomous, community-based discussions focusing on civics and citizen participation, along with supplementary mate- rials that include learning modules and new-media materials. International Writer-in-Residence (Aug 2014 - Feb 2015) NTU (NANYANG UNIVERSITY), Singapore. Continued work on my novel on systemic corruption in Philippine politics; taught crea- tive writing to undergraduates. Radcliffe Fellow (Sept 2013 - May 2014) HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge, USA. Began work on a novel on corruption, at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard. PhD, English Literature and Creative Writing (2008 - 2011) UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE, Adelaide, Australia. MFA, Creative Writing (2002 - 2004) COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, New York, USA. Certificate in Photographic Studies (2001) PARIS PHOTOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE (SPEOS), Paris, France. Bachelor of Arts, English Literature (graduated 2001) ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY, Manila, Philippines. JUDGING: 2013 to present: Member of the Academy, The Folio Prize. UK-based international literary award, with a rotating jury of the world’s top authors. 2013: Juror, Writers Trust Fiction Prize. One of Canada’s top prizes, juried by three established Canadian authors. 2011: Juror: Neustadt International Prize for Literature. US-based biennal prize for lifetime achievement, juried by five international authors. 91 of 9 SELECT WORK: WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM - CULTURAL LEADER (September 2018) Invited to participate in events, and speak on a panel on pluralism, at the Southeast Asian summit in Hanoi, Vietnam. -

A Marineâ•Žs Murder Trial and the Drug War: the •Œdelicate Balanceâ•Š of Criminal Justice in the Philippines

A MARINE’S MURDER TRIAL AND THE DRUG WAR: THE “DELICATE BALANCE” OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN THE PHILIPPINES Peter G. Strasser* ABSTRACT: This article draws on the murder trial of U.S. Marine Joseph Pemberton, who killed a Filipino transgender, to examine aspects of the Philippine criminal justice system. Deep- rooted institutional deficiencies for police, prosecutors, and trial courts, a backlog of thousands of cases, and overpopulated pretrial detention facilities have created a crisis that currently exists within the criminal justice system. The country’s “war on drugs” has served to reinforce the perception that justice in the Philippines is only for the influential and wealthy. Filipinos have wryly noted that for the poor, there is really no justice, just-“tiis,”—which, in the vernacular means “just endure suffering.” Challenging the entrenched, cultural resistance that has frustrated previous reform efforts, the newly appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court has vowed to institutionalize changes designed to expedite the administration of justice. On a practical level, the question in most criminal cases is not whether the accused committed the crime, but rather what is the fairest, most expeditious method to handle the particular offense and offender. As detailed herein, the end goal of justice in the Philippines is restoration of social harmony. Along those lines, this article argues that creative use of legally recognized procedures such as plea bargains and barangay (community) mechanisms, utilizing reconciliation and financial settlements, can help overcome significant barriers in terms of reaching an otherwise seemingly elusive justice. * A former partner with the New Orleans office of Chaffe McCall, LLP, the author earned his J.D.