Was Established As the First Government Secondary School in the Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoskins Family

SHEER DRIVING PLEASURE INSPIRED BY NATURE LOCAL SCHOOLS MEET THE EPWORTH SCHOOL AND ST. CHARLES COLLEGE HOSKINS FAMILY INSPIRED LIVING NATURALLY EDITION 7 INTABA RIDGE MAGAZINE 1 dare to bring your dreams to life S A G N E L L I A S S O C I A T E A R C H I T E C T S 49 Richefond Circle | Suite 1 | Ridgeside Office Park | Umhlanga Rocks Tel: 031 536 8160 | Cell: 082 772 4426 | [email protected] www.sagnelli.com 2 INTABA RIDGE MAGAZINE CONTENTS dare to bring your dreams to INTABA RIDGE CONTENTS e FROM THE DEVELOPER lif An update from our wonderful developer, 5 Brendan Falkson, on the latest happenings in the Estate. 6 SHEER DRIVING PLEASURE - 6 INSPIRED BY NATURE Residents enjoyed Sundowners with Jackie Cameron, hosted by BMW Supertech at Intaba Ridge Estate BMW SUPERTECH JOINS 10 INTABA RIDGE Discover sheer driving pleasure with BMW's ultra-luxurious SUV's MEET THE FAMILY 14 Get to know the beautiful, blended Hoskins family of 6! LOCAL SCHOOLS Discover the local schools available to 22 your children. 22 Contact information Should you require any information regarding the estate, please contact any of the following persons: ESTATE MANAGER SALES Gavin Sibbald | (033) 940 0362 (087) 195 0701 or [email protected] ESTATE ADMIN ADVERTISING SALES & MARKETING Laurin Jansen van Rensburg | [email protected] Kamal | (084) 306 1414 or [email protected] ESTATE GATEHOUSE ESTATE FINANCE (033) 940 0368 Mike Acutt | [email protected] S A G N E L L I A S S O C I A T E A R C H I T E C T S PUBLISHER OFFICE NUMBER | 032 946 0357 -

The DHS Herald

The DHS Herald 23 February 2019 Durban High School Issue 07/2019 Head Master : Mr A D Pinheiro Our Busy School! It has been a busy week for a 50m pool, we have been asked School, with another one coming to host the gala here at DHS. up next week as we move from the summer sport fixtures to the This is an honour and we look winter sport fixtures. forward to welcoming the traditional boys’ schools in Durban This week our Grade 9 boys to our beautiful facility on attended their Outdoor Leadership Wednesday 27 February. The Gala excursion at Spirit of Adventure, starts at 4pm. Shongweni Dam. They had a great deal of fun, thoroughly enjoying Schools participating are: their adventure away from home, Contents participating in a wide range of Westville Boys’ High School activities. A full report will be in Kearsney College Our Busy School! 1 next week’s Herald. Clifton College Sport Results 2 Glenwood High School Weeks Ahead 3 The Chess boys left early Thursday Northwood School This Weekend’s Fixtures 3 morning for Bloemfontein to Durban High School participate in the Grey College MySchool 3 Chess Tournament. This is a The Gala is to be live-streamed by D&D Gala @ DHS 4 prestigious tournament, with 16 of DHS TV, so you can catch all the Rugby Fixtures 2019 4 our boys from Grades 10 to 12 action live if you are not able to competing against 22 schools from attend. Go to www.digitv.co.za to around the country. A full report sign up … it’s free! of their tour will also be found in next week’s Herald. -

Red Black White

MCF #RED BLACK WHITE Directing potential since 1863 12 May 2019 15-2019 From the Headmaster’s Desk Dear Parents and Guardians This week we are focusing on COMMITMENT through our Character Education programme and on Friday, we celebrated Mothers ahead of Mother’s Day on Sunday. In line with the theme on Commitment, College is proud to recognize the long service of a number of our staff members who have served the school with distinction over the past 20, 30 and 40 years. 20-year Service: Mrs Suzanne Webley, Mr Ben Bosch, Mr Jabulani Mhlongo, Mrs Carol Smith, Mr Ken Hackland 30-year Service: Mr Sipho Zondi 40-year Service: Mrs Hazel Miller Boys were reminded of COMMITMENT TO ACADEMICS, with mid- year exams fast approaching, and the need to start revising and preparing, making use of chosen study and revision techniques, and where necessary, attending additional lessons after school. In recognition of Mother’s Day, we asked our boys to bring their mother or mother-figure in their lives to support them and watch them play on Saturday against DHS. There was also the chance to have a photo taken with “Mom” at the Pop-up Photo booth and give her a homemade biscuit. At College, we pay tribute to all our “Moms” who make such a difference in our lives. So what do Mothers want from their sons? • For you to be truly happy and safe • For you to have close, decent friends and to treasure friendship • For you to be proud of yourself and to build esteem in others • For you to have a zest for life and an enthusiasm for ensuring that you extricate the marrow -

From the Head of School's Desk

Term 3, edition 1 2018 From the Head of School’s Desk Half term is a wonderful respite in a very busy year. While we all look forward to time away from school, we do need to take cognisance of the girls’ involvement in all school activities so far this term. There has been great excitement around our official birthday celebration and we hope you have enjoyed the video of the day. This newsletter will confirm the many highlights. I would like to comment on our “piping hot” beginning to half term. We were thrilled to officially reopen and rededicate the Epworth Chapel in January this year, especially as it is our 120th year and 60 years after the completion of the building of the Chapel. We moved the choir from the gallery to the front of the Chapel, providing a stage area for worship and performances, opened up the transepts to increase visibility and improve acoustics, and most recently, installed a new organ in such a way as to complement the original architecture of the building. This project required particular sensitivity given the place the Epworth Chapel has in the hearts of the extended Epworthian community. We are grateful to the school’s architects (Jeremy and Patrick Hathorn) for the sensitive way in which they have remodelled the space and to the contractors and cabinet makers for their superb handiwork. We are delighted with the result, and already the venue has been used for major chapel services, a number of concerts including “Singing in Time” which saw a sizeable orchestra and choir on stage, and the Prep School’s recent production of “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat”. -

Newsletter First Edition Vol.2 the Inlander

NEWSLETTER FIRST EDITION VOL.2 THE INLANDER Welcome to the latest edition battle in the middle: our Administrators, Umpires, of THE INLANDER, your Scorers, and Coaches – who give so freely of their quarterly update on all things time to ensure that we can in fact do, what we love cricket at the KwaZulu Natal to do. Cricket Union : Inland. I would like to wish each and every player and team It is hard to believe that we are already well into the the best of luck for the season, play hard but at all new cricket season – All the pre-season prep work is times play with humility and respect. But above all, now a thing of the past, as our provincial, club and make sure you are having fun doing it! schools cricket programmes are in full swing. This is the time of year when we as fans of the game Ritesh Ramjee get to dust off our equipment, get out onto the ovals Amateur Manager around our province and play this great sport that we all love. As players of this great game, we must always remember the tireless work of the people not doing NEWSLETTER FIRST EDITION VOL.2 THE INLANDER CONTENT P1 Amateur Manager Message P2 Amateur Department Contact Details P3 Player Profile – Senior Ladies P4 Annual KFC Mini Cricket Provincial Seminar P5 Youth Cricket P10 Coaches Education P11 Club Log Position P12 Shane Burger – KZN Inland Warm up Routine P13 Hub Players that were selected for the Various National Week Teams 2016 Amateur Department Details Amateur Manager Ritesh Ramjee 074 948 6397 [email protected] Academy Coach/ Coaching Manager Desigan Reddy -

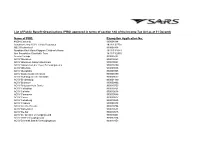

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Behind Every Good List, There Lies a Determined

CAREERS Careers, 18-Oct-2009-Page 11, Cyan Careers, 18-Oct-2009- Page 11, Magenta Careers, 18-Oct-2009-Page 11, Yellow Careers, 18-Oct-2009- Page 11, Black C-1 JDCP Sing the praises of these state schools Champions stand proud in SA’s public education landscape THE Sunday Times commissioned the “The intention of this was to reward University of the Witwatersrand’s visiting schools for the total number of pupils researcher Helen Perry to identify the Top encouraged to do these subjects, as well as 100 government schools in the country. how well these pupils did in the exams. The matrics of 2008, on which the survey “In so doing, we avoid unduly rewarding is based, are the first graduates of the new schools that selected only their best stu- curriculum introduced in stages 12 years dents to sit for these subjects.” ago. Schools with 50 or more pupils were The Sunday Times has revived the To p considered for the survey. 100 schools project, last undertaken by the The index considers academic achieve- newspaper 10 years ago, to give its readers ment and is calculated by combining these the information necessary to make “the five factors: single most important decision parents ■ Matric pass rate; will make — where to educate their chil- ■ Percentage of pupils with a university dren”, said Sunday Times editor Mondli entrance pass; M a k h a nya . ■ The average number of A symbols; “We also want to celebrate schools that ■ The number of maths candidates achieving have achieved excellence, demonstrate over 50%, as a percentage of all candidates why they performed so well, and highlight at the school; the top schools as role models for others to ■ The number of science candidates achiev- learn from,” he said. -

Report on the National Senior Certificate Examination Results 2010

EDUCATIONAL MEASUREMENT, ASSESSMENT AND PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS 2010 REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS • 2010 His Excellency JG Zuma the President of the Republic of South Africa “On the playing field of life there is nothing more important than the quality of education. We urge all nations of the world to mobilise in every corner to ensure that every child is in school” President JG Zuma 1 EDUCATIONAL MEASUREMENT, ASSESSMENT AND PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS The Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, MP recently opened the library at the Inkwenkwezi Secondary School in Du Noon on 26 October 2010 and encouraged learners to read widely and this will contribute to improving their learning achievement. The Minister of Basic Education, Mrs Angie Motshekga, MP has repeatedly made the clarion call that “we owe it to the learners, the country and our people to improve Grade 12 results as committed”. 2 REPORT ON THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION RESULTS • 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD BY MINISTER . 7 1. INTRODUCTION . 9 2. THE 2010 NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE (NSC) EXAMINATION . 10 2.1 The magnitude and size of the National Senior Certificate examination . 10 2.2 The examination cycle . 11 2.3 Question Papers . 15 2.4 Printing, packing and distribution of question papers . 18. 2.5 Security . 19 2.6 The conduct of the 2010 National Senior Certificate (NSC) . 19 2.7 Processing of marks and results on the Integrated Examination Computer System (IECS) . 20 2.8 Standardisation of the NSC Results . 21 2.9 Viewing, remarking and rechecking of results during the appeal processes . -

South Africa's Exclusive Schools

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL TOURISM AND GLOBAL LEARNING IN SOUTH AFRICAN HIGH SCHOOL LEARNERS by CHRISTINE ANNE McGLADDERY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PhD in Tourism Management in the FACULTY OF ECONOMIC AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA Supervisor: Professor Berendien Anna Lubbe Co-Supervisor: Professor Jarkko Saarinen August 2016 - i - © University of Pretoria - ii - © University of Pretoria ABSTRACT There is a growing demand in the literature for rigorous empirical research to test the underpinning assumption of international education theory, namely that global learning occurs as a consequence of international travel. Through the application of a global learning survey instrument to 1152 Grade 11 learners in 16 South African exclusive independent high schools, evidence is provided to indicate that significant global learning only occurs when the international travel experience is facilitated to encourage learning, when there is a desire by learners to engage with cultural differences at their travel destination, and when learners feel comfortable expressing their opinions within their tour group. Furthermore, some types of international educational tourism are more conducive to global learning than others. Additionally, a conceptual, process-driven model of international educational tourism is proposed based on the synthesis of educational tourism, international education, experiential education and global learning theories. The model is tested and refined through analysis of the data collected from the questionnaire. By conceptualising educational tourism as a process it overcomes the limitations associated with segment- based definitions and in doing so demonstrates the potential for hybridising educational tourism with other sectors of the industry. Finally, owing to the expense involved with international travel, non-travel related factors are identified which encourage global learning in high school children. -

The Classics, the Cane and Rugby: the Life of Aubrey Samuel Langley and His Mission to Make Men in the High Schools of Natal, 1871-1939

The Classics, the Cane and Rugby: The Life of Aubrey Samuel Langley and his Mission to Make Men in the High Schools of Natal, 1871-1939. by Dylan Thomas Löser Supervisor: Robert Morrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Social Science (Masters) Degree in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town. February 2016 University of Cape Town 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town For ‘Bull’ and ‘Nancy’, who shared the journey with me. 2 Acknowledgements: First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Robert Morrell. His enthusiasm, erudite advice and friendship have proved invaluable in coming to terms with Langley. In a similar vein, I would like to thank Dr Vanessa Noble for assisting me with my earlier honours thesis. It was during this adventure that I developed the urge to tell Langley’s story. Secondly, I would also like to thank Jean Thomassen. This thesis would have never taken flight if it were not for her efforts in unearthing documents relating to Langley and putting me in contact with fellow members of the Langley family. Thirdly, I would like to thank Jackie Harris, Julia Martin, Michael Cope, and Jolyon and Michael Nuttall for the selfless way in which they shared stories and anecdotes relating to Langley with me. -

011 – OBITUARY for DENIS EMERY

South African National Society History - Culture and Conservation. Join SANS. Founded in 1905 for the preservation of objects of Historical Interest and Natural Beauty http://sanationalsociety.co.za/ PO Box 47688, Greyville, 4023, South Africa Email: [email protected] | Tel: 071 746 1007 NEWS BRIEF OBITUARY DENIS EMERY SLANEY – 14 NOVEMBER 1929 TO 11 FEBRUARY 2015 Denis Slaney was born in Durban and grew up in Overport near Overport House and McCord’s Hospital. He was educated at Durban High School and studied at the University of Natal [Pietermaritzburg]. He trained to be a teacher and on leaving university taught for one term at Port Shepstone High School before being posted to Estcourt High School where he taught history and geography for the next twenty years. He in fact taught, or as he liked to put it “tried to teach” his future wife, Dawn Hope, for four years. Twenty years later they married in1971. Shortly afterwards Denis was promoted as Vice Principal and Head of History at Northlands Boys’ High School and they moved to Durban. He and Dawn lived at Westville where soon after their arrival their son Kevin was born. They lived there for the next forty-two years. Although Denis was a strict disciplinarian, he won the respect of his pupils as a result of his fairness and the ability to pass on his knowledge. Dawn and Kevin were touched by the number of past pupils who contacted them and remembered Denis with affection. From Northlands Denis was promoted to Head Master of Brettonwood High School and finally Head Master of George Campbell High School. -

Chronicle for 1955

r- -J-SM: KEARSNEY j. COLLEGE CHRONICLE O#?PE o\t^ ■im July, 1955 '. "sy KEARSNEY COLLEGE CHRONICLE WPE D\^ July, 1955 m m M ipt m A / m 8® © w SCHOOL LAYOUT, INCLUDING PEMBROKE HOUSE. Kearsney College Chronicle Vol. 4, No. I July, 1955 ON SCHOOL MAGAZINES I think It will be generally agreed that, except for those most intimately concerned, School Magazines would not be classified among the "best sellers". They contain none of the features which attract the common herd, not even a bathing beauty on the cover (though it's an idea). Their interest-value is very local; to the outsider, the lists of event-winners or prize-winners have the monotony of a telephone directory, and does it really matter whether we won the match or lost it? Only to those most closely concerned does it matter. What, Magazine Reader, do you look for? Let's be honest. Yes, of course. You turn over hastily to those places where your own name is likely to appear: your own name, gold-embroidered, standing there for everyone to see, if it were not for the fact that they are too busy looking for their own names. That done, what else is there of interest? Well—you already knew the results of the matches, so that is not news; the activities of your Society are known to you and of no interest to anyone else; the Old Boys' News is just a catalogue of unknown names; articles are boring, except for the writers. Yes, surely this is not a best-seller.