Attachment and Touch 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

Attachment, Locus of Control, and Romantic Intimacy in Adult

ATTACHMENT, LOCUS OF CONTROL, AND ROMANTIC INTIMACY IN ADULT CHILDREN OF ALCOHOLICS: A CORRELATIONAL INVESTIGATION by Raffaela Peter A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Education in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 Copyright Raffaela Peter 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family members and friends for their continuous support and understanding during this process of self-exploration which oftentimes called for sacrifices on their part. Not to be forgotten is the presence of a very special family member, Mr. Kitty, who silently and patiently witnessed all colors and shapes of my affective rainbow. Val Santiago Stanley has shown nothing but pure, altruistic friendship for which I will be forever grateful. The appreciation is extended to Val’s Goddesses Club and its members who passionately give to others in the community. Many thanks go out to Jackie and Julianne who, with true owl spirit and equipped with appropriate memorabilia, lent an open ear and heart at all times. Thank you to my committee who provided me with guidance and knowledge throughout my journey at Florida Atlantic University. Most of them I have known for nearly a decade, a timeframe that has allowed me to grow as an individual and professional. To Dr. Paul Ryan Peluso, my mentor and fellow Avenger, thank you for believing in me and allowing me to “act as if”; your metaphors helped me more than you will ever know. You are a great therapist and educator, and I admire your dedication to the profession. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

Relations Between Remembered Childhood Parental Acceptance-Rejection, Current Fear of Intimacy, and Psychological Adjustment Among Pakistani Adults

Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal ISSN 2474-7688 Review Article Psychol Behav Sci Int J Volume 10 Issue 2 - December 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Abdul Khaleque DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2018.10.555784 Relations between Remembered Childhood Parental Acceptance-Rejection, Current Fear of Intimacy, and Psychological Adjustment among Pakistani Adults Abdul Khaleque1*, Sadiq Hussain2, Sana Gul2 and Samar Zahra2 1Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Connecticut, USA 2Department of Behavioral Sciences, Karakoram International University, Pakistan Submission: October 02, 2018; Published: December 11, 2018 *Corresponding author: Abdul Khaleque, PhD, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Unit 1058, University of Connecticut, 348 Mansfield Road Storrs, CT 06269-2058, USA Abstract This study examined the relations between remembered childhood parental acceptance-rejection, fear of intimacy, and psychological adjustment in adulthood among Pakistani young, middle, and older adults. The sample consisted of a total of 366 (55.7% females) participants from Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) in Pakistan. Among them 182 were young adults (60.9% females), 92 middle adults (52.1% females), and 92 older adults (48.9% females). The samples responded to 5 self-report measures: Adult Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for mothers and fathers (short forms), Interpersonal Relationship Anxiety Questionnaire, Adult Personality Assessment Questionnaire (short form), and Fear of anxiety,Intimacy and Scale. fear Results of intimacy showed than that did only accepted male youngadults adultsin all age perceived groups, toexcept be more older rejected adults. by their mothers and fathers as compared to female young adults. Rejected adults (by both mother & father) reported higher levels of psychological maladjustment, interpersonal relationship relationship anxiety, and fear of intimacy for both male and female respondents of all age groups, except older adults. -

Parental Bonding, Adult Romantic Attachment, Fear of Intimacy, and Cognitive Distortions Among Child Molesters

PARENTAL BONDING, ADULT ROMANTIC ATTACHMENT, FEAR OF INTIMACY, AND COGNITIVE DISTORTIONS AMONG CHILD MOLESTERS Eric Wood, MS Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2007 APPROVED: Shelley Riggs, Major Professor James Quinn, Committee Member Kimberly Kelly, Committee Member Richard Rogers, Committee Member Linda Marshall, Chair of the Department of Psychology Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Wood, Eric. Parental bonding, adult romantic attachment, fear of intimacy, and cognitive distortions among child molesters. Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology), August 2007, 127 pp., 18 figures, 9 tables, references, 231 titles. Path models assessed different models of influential order for parental bonding; adult romantic attachment; views of self, world/others, and the future; the fear of intimacy; and cognitive distortions among child molesters and non-offending controls. Child molesters receiving sex offender treatment reported more problematic parental bonding; insecure adult romantic attachment; negative views of self, world/others, and the future; a greater fear of intimacy, and more cognitive distortions regarding adult-child sex. The predicted path models were not established as the models did not adequately fit the data. However, post hoc logistic regressions indicated that Maternal Optimal Bonding, Preoccupied attachment, and cognitive distortions regarding adult-child sex significantly predicted child molester status. Overall, the findings provide support for a multi-factorial model of child molestation derived from attachment theory. Limitations of the study and areas for future research are also discussed. Copyright 2007 by Eric Wood ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES...........................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... -

The Meaning of Intimacy for Men Who Are Gay

THE MEANING OF INTIMACY FOR MEN WHO ARE GAY by David Loran A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Counseling Psychology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 2007 © David Loran, 2007 Abstract Intimacy has been cited as primary psychological need by many psychologists, including Rogers, Maslow, and Erikson. Others claim intimate relationships provide benefits for both the mind and body. Despite its importance, there continues to be disagreement as to how intimacy should be defined. Research suggests that the meaning of intimacy may vary according to the type of relationship involved or the gender, age, or cultural identity of the referent. Yet there exists almost no literature attempting to understand the meaning of intimacy for men who are gay. As gay relationships become more open and accepted, practitioners will find themselves dealing with questions of intimacy between men who are gay. In order to better serve the clients, it will be important to have a common reference point. This phenomenological study serves to advance the field by asking men who are gay to define intimacy using their own long-term relationship as a reference point. After interviewing men who are gay in Vancouver, Canada, the author conducted an analysis of the interviews and categories and themes were developed to help explain what intimacy means to men who are gay. These themes include the development of intimacy as a process, togetherness, openness, perceptions of commonalities between partners, the need for individuation and time spent apart, growth within oneself and growth within the relationship, effort required to develop and maintain intimacy, commitment, support, the role of emotions in intimacy, physical demonstrations of intimacy, sexuality, the varying levels and forms of intimacy, the influence of role models, and the need to overcome challenges in developing intimate relationships. -

Exploring and Measuring the Perceived Impact of Visible Difference Upon Romantic Relationships Nicholas David Sharratt a Thesis

Exploring and Measuring the Perceived Impact of Visible Difference upon Romantic Relationships Nicholas David Sharratt A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences, University of the West of England November 2020 Table of Contents i. Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 9 ii. Acknowledgements and Dedications .......................................................................... 10 iii. Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 11 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 1.1. Introduction to this Thesis ...................................................................................... 13 1.2. Overview of this Chapter ........................................................................................ 13 1.3. Intimacy and Romantic Relationships ..................................................................... 13 1.3.1. Intimacy and Romantic Relationships ............................................................. 13 1.3.2. The Benefits of Intimate, Romantic Relationships .......................................... 16 1.3.3. Attraction and Attractiveness ........................................................................ -

Psychotherapists' Beliefs and Attitudes Towards

PSYCHOTHERAPISTS’ BELIEFS AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS POLYAMORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY SHANNON L. STAVINOHA, M.A. DENTON, TEXAS AUGUST 2017 TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DENTON, TEXAS July 01, 2016 To the Dean of the Graduate School: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Shannon L. Stavinoha entitled “Psychotherapists’ Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Polyamory.” I have examined this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Counseling Psychology. _______________________________ Jeff Harris, Ph.D., Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: ____________________________________ Debra Mollen, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Claudia Porras Pyland, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Lisa Rosen, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Shannon Scott, Ph.D., Department Chair Accepted: _______________________________ Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © Shannon L. Stavinoha, 2016 all right reserved. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge and share my personal gratitude with those who were involved in this project. I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Harris for his valuable assistance, tireless guidance, patience, and belief in me. I would also like to acknowledge the following professors at Texas Woman's University: Dr. Stabb, Dr. Rubin, and Dr. Mollen for their support and guidance. I am grateful to Dr. Rosen and Dr. Porras-Pyland, who served as valuable members of my dissertation committee. I would like to thank my mother, my eternal cheerleader, for walking by my side through all the ups and the downs and always supporting me; I owe it all to you. -

Fear of Intimacy in Romantic Relationships During Emerging

Fear of Intimacy in Romantic Relationships During Emerging Adulthood: The Influence of Past Parenting and Separation- Individuation Submitted by Marianne Elizabeth Lloyd Bachelor of Behavioural Science Postgraduate Diploma in Psychology A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Psychology (Clinical Psychology) School of Social Sciences and Psychology Faculty of Arts, Education and Human Development Victoria University August 2011 FEAR OF INTIMACY IN ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS Abstract Intimacy is a central component of romantic relationships with the development of a capacity for intimacy regarded as being one of the milestones of adulthood. Fear of intimacy has been defined as “the inhibited capacity of an individual, because of anxiety to exchange thoughts and feelings of personal significance with another individual who is highly valued” (Descutner & Thelen, 1991, p. 219). Although a number of studies have focused on fear of intimacy, there has been limited research on the factors that might influence fear of intimacy. Past experience in the parent-child relationship has been found to influence both the capacity to form romantic relationships and separation-individuation. Establishing a romantic relationship and leaving the parental home have both been identified as important markers of adulthood, however current Australian statistics indicate that, compared to previous decades, in the period of emerging adulthood (18-25 years) fewer individuals are involved in a romantic relationship and a higher percentage of young people are living at home with their parents. The relationship between these social trends and past parenting, separation- individuation and fear of intimacy has not been explored. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the influence of past parenting (perceived maternal care and overprotection), and separation-individuation on young adults’ fear of intimacy regarding heterosexual partner relationships. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

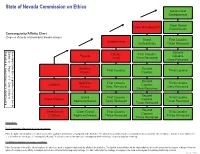

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

The Phobias That Cause Misery for Millions This Valentine's

The Phobias That Cause Misery for Millions this Valentine’s Day Submitted by: Kin Communications2 Thursday, 13 February 2020 The Phobias That Cause Misery for Millions this Valentine’s Day •Phobia Guru reveals the top five phobias which can cripple or prevent relationships • For those with a fear of love or intimacy it can be impossible to form romantic relationships •Free audio download to cure relationship phobias this Valentine’s Day February 2020 While for many Valentine’s Day represents a day of romance, flowers and affection for others the 14th of February is a dreadful reminder of anxiety. Adam Cox, a Harley Street based Phobia Guru (https://www.phobiaguru.com/) has identified the leading phobias that prevent or hinder relationships. Adam also warns that while these phobias are more front of mind on Valentine’s Day, they could be affecting relationships year-round. While it sounds strange many people have a fear of love or intimacy. This can come from a sensitising event such as a particularly emotional break-up or an unpleasant early sexual experience. For those with Androphobia and Gynophobia, the fears of men and women respectively, their phobia can stop them even approaching another person. This can interfere with both platonic and physical relationships, particularly making the Valentine’s period a time of anxiety for sufferers. Adam has revealed the most common relationship related phobias. •Philophobia (https://www.phobiaguru.com/fear-of-love-philophobia.html) - The fear of love, which causes sufferers to be frightened of falling in love or developing emotional attachments. People with this condition tend to overthink every possible reason why a person may not be compatible which adds pressure on the early stages of dating.