Roundtable on Anti-Semitism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1 The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought Department Website: http://socialthought.uchicago.edu Chair • Robert Pippin Professors • Lorraine Daston • Wendy Doniger • Joel Isaac • Hans Joas • Gabriel Lear • Jonathan Lear • Jonathan Levy • Jean Luc Marion • Heinrich Meier • Glenn W. Most • David Nirenberg • Thomas Pavel • Mark Payne • Robert B. Pippin • Jennifer Pitts • Andrei Pop • Haun Saussy • Laura Slatkin • Nathan Tarcov • Rosanna Warren • David Wellbery Emeriti • Wendy Doniger • Leon Kass • Joel Kraemer • Ralph Lerner • James M. Redfield • David Tracy About the Committee The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought was established as a degree granting body in 1941 by the historian John U. Nef (1899-1988), with the assistance of the economist Frank Knight, the anthropologist Robert Redfield, and Robert M. Hutchins, then President of the University. The Committee is a group of diverse scholars sharing a common concern for the unity of the human sciences. Their premises were that the serious study of any academic topic, or of any philosophical or literary work, is best prepared for by a wide and deep acquaintance with the fundamental issues presupposed in all such studies, that students should learn about these issues by acquainting themselves with a select number of classic ancient and modern texts in an inter- disciplinary atmosphere, and should only then concentrate on a specific dissertation topic. It accepts qualified graduate students seeking to pursue their particular studies within this broader context, and aims both to teach precision of scholarship and to foster awareness of the permanent questions at the origin of all learned inquiry. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

The Refugee Resettlement Process to the United States

The Refugee Resettlement Process to the United States About HIAS HIAS Fast Facts Founded in the 1880s to help resettle Jews In Fiscal Year 2017, HIAS fleeing persecution, HIAS is the world’s • resettled 3,299 refugees to the oldest refugee agency. Today, guided by our United States Jewish values and history, we bring more • resettled refugees of 38 nationalities than 130 years of expertise to our work to the United States providing services to all refugees in need of • resettled 647 Special Immigrant Visa assistance, regardless of their national, holders to the United States ethnic, or religious background. • 70 percent of HIAS clients joined a friend or family member in the United States Who is a refugee? Refugees are people who have a very real fear of persecution because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. They have fled human rights abuse or conflict, and have sought asylum outside their home country. Most of them are women and children. How many refugees are there? Refugee resettlement and protection is more important now than ever. According to the UN refugee agency, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are 65 million displaced persons worldwide, of which 22.5 million are refugees. UNHCR identified 1.2 million of those as needing resettlement to a third country. Resettlement is the last resort for refugees. Fewer than one percent are considered for resettlement. The U.S. historically has resettled the most vulnerable refugees, including female-headed households, victims of torture, LGBT refugees, and people with extreme medical needs. -

Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews

"Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" By Maddalena Marinari University of Kansas, 2009 B.A. Istituto Universitario Orientale Submitted to the Department of History and the Faculty of The Graduate School of the University Of Kansas in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Defended: 14 December 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Maddalena Marinari certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" Committee: __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Approved: 14 December 2009 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 1: From Unwanted to Restricted (1890-1921) ………………………………………...17 Chapter 2: "The doors of America are worse than shut when they are half-way open:" The Fight against the Johnson-Reed Immigration -

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

RACIAL SEGREGATION and the ORIGINS of APARTHEID, 1919--36 Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36

RACIAL SEGREGATION AND THE ORIGINS OF APARTHEID, 1919--36 Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36 Saul Dubow, 1989 Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-20043-6 ISBN 978-1-349-20041-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20041-2 © Saul Dubow, 1989 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover Ist edition 1989 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1989 ISBN 978-0-312-02774-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Racial segregation and the origins of apartheid in South Africa. 1919-36/ Sau1 Dubow. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-312-02774-2 1. Apartheid-South Africa-History-20th century. I. Dubow, Saul. DT763.R34 1989 88-39594 968.05'3--dc19 CIP Contents Pre/ace vii List 0/ Abbreviations x Introduction 1 PART I 1 The Elaboration of Segregationist Ideology, c. 1900-36 21 1 Early Exponents of Segregation 21 2 'Cultural Adaptation' 29 3 Segregation after the First World War 39 4 The Liberal Break with Segregation 45 2 Segregation and Cheap Labour 51 1 The Cheap-Iabour Thesis 51 2 The Mines 53 3 White Labour 56 4 Agriculture 60 5 The Reserves 66 6 An Emergent Proletariat 69 PART 11 3 Structure and Conßict in the Native Affairs Department 77 1 The Native Affairs Department (NAD) 77 2 Restructuring the NAD: the Public Service Commission, 1922-3 81 3 Conftict within the State and the Native Administration Bill ~ 4 'Efficiency', 'Economy' and 'Flexibility' -

What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol

Hofstra Law Review Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 22 2004 Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti- Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 32: Iss. 4, Article 22. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol32/iss4/22 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tel LOVE WITH A PROPER STRANGER: WHAT ANTI-MISCEGENATION LAWS CAN TELL US ABOUT THE MEANING OF RACE, SEX, AND MARRIAGE Rachel F. Moran* True love. Is it really necessary? Tact and common sense tell us to pass over it in silence, like a scandal in Life's highest circles. Perfectly good children are born without its help. It couldn't populate the planet in a million years, it comes along so rarely. -Wislawa Szymborskal If true love is for the lucky few, then for the rest of us there is the far more mundane institution of marriage. Traditionally, love has sat in an uneasy relationship to marriage, and only in the last century has romantic love emerged as the primary, if not exclusive, justification for a wedding in the United States. -

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

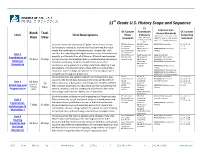

11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence

th 11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence C3 Common Core DC Content Framework DC Content Block Trad. Literacy Standards Unit Unit Descriptions Power Indicators RH.11-12.1, 11-12.2, 11-12.10 Supporting Days Days Standards D3.1, D4.3 and WHST.11-12.4, 11-12.5, 11-12.9 Standards D4.6 apply to each and 11-12.10 apply to each unit. unit. Students review the content of 8th grade United States History 11.1.6: Influences D1.4: Emerging RH.11-12.4: Vocabulary 11.1.1-11.1.5 on American questions 11.1.8 (colonization, revolution, and civil war) by examining the major Revolution D4.2: Construct WHST.11-12.2: Explanatory 11.1.10 trends from colonialism to Reconstruction. In particular, they 11.1.7: Formation explanations Writing of Constitution Unit 1 consider the expanding role of government, issues of freedom and 11.1.9: Effects of Apply to each unit: Apply to each unit: Foundations of equality, and the definition of citizenship. Students read complex Civil War and D3.1: Sources RH.11-12.1: Cite evidence 10 days 20 days primary sources, summarizing based on evidence while developing Reconstruction D4.3: Present RH.11-12.2: Central idea American historical vocabulary. Students should communicate their information RH.11-12.10: Comprehension D4.6: Analyze Democracy conclusions using explanatory writing, potentially adapting these problems WHST.11-12.4: Appropriate explanations into other formats to share within or outside their writing classroom. Students begin to examine the relationship between WHST.11-12.5: Writing process WHST.11-12.9: Using evidence compelling and supporting questions. -

Why the Success of Exodus in 1950S America? by Stephanie Schey Capstone Advisor: Dr. Lisa Moses Leff Spring Semester, 2011 Unive

Why the Success of Exodus in 1950s America? By Stephanie Schey Capstone Advisor: Dr. Lisa Moses Leff Spring Semester, 2011 University Honors in Jewish Studies College of Arts and Sciences: Jewish Studies 2 Capstone Abstract The positive reception of Exodus , by Leon Uris, in mainstream America during the 1950s is a phenomenon that has been largely overlooked. Arguably too much attention has been directed towards the aftermath of the book and film, without properly situating the novel in the context of current events and public opinion on Judaism and Israel at the time of its release. In order to establish a thorough framework within which to examine the legacy of Exodus , it is essential to understand American society at the time of publication and assess the impact of current events, such as the founding of the state of Israel and the 1956 Suez Crisis, upon the novel’s audience. In so doing, we learn a great deal about America’s attitudes toward Judaism and Israel. This paper explores the climate in America that allowed for the novel's positive reception, identifying the three strongest motivational factors for reading Exodus as: 1) Israel’s portrayal in the media, 2) suburban integration, and 3) Holocaust memory. Divided into three chapters, each portion of the paper analyzes one facet of America’s changing image of Israel or Judaism at the time of the novel’s publication in 1958. 3 Introduction The novel Exodus , written by Leon Uris, was published on September 18, 1958 and commanded immediate fame. Were his words the truth, Uris’s novel could have served as a creation myth for the state of Israel, inspiring nationalism amongst world Jewry and providing heroes for a downtrodden post-Holocaust generation.