A Case Study of Bonaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ix Viii the World by Income

The world by income Classified according to World Bank estimates of 2016 GNI per capita (current US dollars,Atlas method) Low income (less than $1,005) Greenland (Den.) Lower middle income ($1,006–$3,955) Upper middle income ($3,956–$12,235) Faroe Russian Federation Iceland Islands High income (more than $12,235) (Den.) Finland Norway Sweden No data Canada Netherlands Estonia Isle of Man (U.K.) Russian Latvia Denmark Fed. Lithuania Ireland U.K. Germany Poland Belarus Belgium Channel Islands (U.K.) Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Luxembourg France Moldova Switzerland Romania Uzbekistan Dem.People’s Liechtenstein Bulgaria Georgia Kyrgyz Rep.of Korea United States Azer- Rep. Spain Monaco Armenia Japan Portugal Greece baijan Turkmenistan Tajikistan Rep.of Andorra Turkey Korea Gibraltar (U.K.) Syrian China Malta Cyprus Arab Afghanistan Tunisia Lebanon Rep. Iraq Islamic Rep. Bermuda Morocco Israel of Iran (U.K.) West Bank and Gaza Jordan Bhutan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Algeria Libya Arab Rep. Bahrain The Bahamas Western Saudi Qatar Cayman Is. (U.K.) of Egypt Bangladesh Sahara Arabia United Arab India Hong Kong, SAR Cuba Turks and Caicos Is. (U.K.) Emirates Myanmar Mexico Lao Macao, SAR Haiti Cabo Mauritania Oman P.D.R. N. Mariana Islands (U.S.) Belize Jamaica Verde Mali Niger Thailand Vietnam Guatemala Honduras Senegal Chad Sudan Eritrea Rep. of Guam (U.S.) Yemen El Salvador The Burkina Cambodia Philippines Marshall Nicaragua Gambia Faso Djibouti Federated States Islands Guinea Benin Costa Rica Guyana Guinea- Brunei of Micronesia Bissau Ghana Nigeria Central Ethiopia Sri R.B. de Suriname Côte South Darussalam Panama Venezuela Sierra d’Ivoire African Lanka French Guiana (Fr.) Cameroon Republic Sudan Somalia Palau Colombia Leone Togo Malaysia Liberia Maldives Equatorial Guinea Uganda São Tomé and Príncipe Rep. -

The Value of Nature in the Caribbean Netherlands

The Economics of Ecosystems The value of nature and Biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands in the Caribbean Netherlands 2 Total Economic Value in the Caribbean Netherlands The value of nature in the Caribbean Netherlands The Challenge Healthy ecosystems such as the forests on the hillsides of the Quill on St Eustatius and Saba’s Mt Scenery or the corals reefs of Bonaire are critical to the society of the Caribbean Netherlands. In the last decades, various local and global developments have resulted in serious threats to these fragile ecosystems, thereby jeopardizing the foundations of the islands’ economies. To make well-founded decisions that protect the natural environment on these beautiful tropical islands against the looming threats, it is crucial to understand how nature contributes to the economy and wellbeing in the Caribbean Netherlands. This study aims to determine the economic value and the societal importance of the main ecosystem services provided by the natural capital of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba. The challenge of this project is to deliver insights that support decision-makers in the long-term management of the islands’ economies and natural environment. Overview Caribbean Netherlands The Caribbean Netherlands consist of three islands, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba all located in the Caribbean Sea. Since 2010 each island is part of the Netherlands as a public entity. Bonaire is the largest island with 16,000 permanent residents, while only 4,000 people live in St Eustatius and approximately 2,000 in Saba. The total population of the Caribbean Netherlands is 22,000. All three islands are surrounded by living coral reefs and therefore attract many divers and snorkelers. -

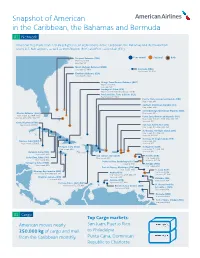

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

St. Lucia Earns Junior Chef Award at Taste Of

MEDIA CONTACTS: KTCpr Theresa M. Oakes / [email protected] Leigh-Mary Hoffmann / [email protected] Telephone: 516-594-4100 #1101 **high resolution images available** BAHAMAS WINS TEAM, BARTENDER, PASTRY TOP HONORS; PUERTO RICO TAKES CHEF CATEGORY; ST. LUCIA EARNS JUNIOR CHEF AWARD AT TASTE OF THE CARIBBEAN 2015 MIAMI, FL (June 15, 2015) – The Bahamas National Culinary Team won three of the five top categories at the Taste of the Caribbean culinary competition this past weekend earning honors as Caribbean National Team of the Year and individual honors to Marv Cunningham, Bahamas for Caribbean Bartender of the Year and four-time winner Sheldon Tracey Sweeting, Bahamas, for Caribbean Pastry Chef of the Year. Jonathan Hernandez, Puerto Rico was crowned Caribbean Chef of the Year and Edna Butcher, St. Lucia, was named Caribbean Junior Chef of the Year. "Congratulations to all of the Taste of the Caribbean participants, their national hotel associations, team managers and sponsors for developing 10 Caribbean national culinary teams to compete at our annual culinary event," said Frank Comito, director general and CEO of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA). "Your commitment to culinary excellence in our region is very much appreciated as we showcase the region’s culinary and beverage offerings. Congratulations to all of the winners for a job well-done," Comito added. Presented by CHTA, Taste of the Caribbean featured cooking and bartending competitions between 10 Caribbean culinary teams from Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, Suriname and the U.S. Virgin Islands with the winners being named the "best of the best" throughout the region. -

Aquaculture and Marine Protected Areas: Exploring Potential Opportunities and Synergies

Aquaculture and Marine Protected Areas: Exploring Potential Opportunities and Synergies To meet the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Target 11 on marine biodiversity protection, Aichi Target 6 on sustainable fisheries by 2020, as well as the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 on food security and SDG 14 on oceans, by 2030, there is an urgent need to reconcile nature conservation and sustainable development. It is also widely recognised that aquaculture significantly contributes to sustainable development in coastal communities and plays a vital role in ensuring food security, poverty alleviation, and economic resilience. In the framework of integrated management, the time has therefore come to identify the potential opportunities and synergies that can enable aquaculture and conservation to work together more effectively. CONTENT Understanding the various types of aquaculture and their potentialities ……………………………………… 3 The types of MPAs and matrix of interactions showing aquaculture & sustainability principles …… 7 Understanding aquaculture and MPA interactions …… 8 Towards MPAs and aquaculture compatibility and sustainability ……………………………………………10 Background In order to feed the world's growing human population, attention will need to increasingly focus on where the protein needs of the world will be supplied from. While capture fisheries have now reached a plateau of production, marine aquaculture of fish, shellfish and algae has been steadily increasing over the past decades and has become a valid option to make up the protein shortfall. However, one of the major constraints for the aquaculture production sector is the availability of, and access to space. In many coastal areas, competition with other marine activities is already high, mainly because the bulk of marine aquaculture is located close to the shore. -

The European Union, Its Overseas Territories and Non-Proliferation: the Case of Arctic Yellowcake

eU NoN-ProliferatioN CoNsortiUm The European network of independent non-proliferation think tanks NoN-ProliferatioN PaPers No. 25 January 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION, ITS OVERSEAS TERRITORIES AND NON-PROLIFERATION: THE CASE OF ARCTIC YELLOWCAKE cindy vestergaard I. INTRODUCTION SUMMARY There are 26 countries and territories—mainly The European Union (EU) Strategy against Proliferation of small islands—outside of mainland Europe that Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Strategy) has been have constitutional ties with a European Union applied unevenly across EU third-party arrangements, (EU) member state—either Denmark, France, the hampering the EU’s ability to mainstream its non- proliferation policies within and outside of its borders. Netherlands or the United Kingdom.1 Historically, This inconsistency is visible in the EU’s current approach since the establishment of the Communities in 1957, to modernizing the framework for association with its the EU’s relations with these overseas countries and overseas countries and territories (OCTs). territories (OCTs) have focused on classic development The EU–OCT relationship is shifting as these islands needs. However, the approach has been changing over grapple with climate change and a drive toward sustainable the past decade to a principle of partnership focused and inclusive development within a globalized economy. on sustainable development and global issues such While they are not considered islands of proliferation as poverty eradication, climate change, democracy, concern, effective non-proliferation has yet to make it to human rights and good governance. Nevertheless, their shores. Including EU non-proliferation principles is this new and enhanced partnership has yet to address therefore a necessary component of modernizing the EU– the EU’s non-proliferation principles and objectives OCT relationship. -

The EU and Its Overseas Entities Joining Forces on Biodiversity and Climate Change

BEST The EU and its overseas entities Joining forces on biodiversity and climate change Photo 1 4.2” x 10.31” Position x: 8.74”, y: .18” Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores Madeira French Guadeloupe Canary Guiana Martinique islands Reunion Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Anguilla British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores Aruba Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique Aruba French Guiana Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Reunion Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land ORs OCTs Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. A major potential for cooperation on climate change and biodiversity Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. -

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba and the European Netherlands Conclusions

JOINED TOGETHER FOR FIVE YEARS BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS, SABA AND THE EUROPEAN NETHERLANDS CONCLUSIONS Preface On 10 October 2010, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba each became a public entitie within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In the run-up to this transition, it was agreed to evaluate the results of the new political structure after five years. Expectations were high at the start of the political change. Various objectives have been achieved in these past five years. The levels of health care and education have improved significantly. But there is a lot that is still disappointing. Not all expectations people had on 10 October 2010 have been met. The 'Committee for the evaluation of the constitutional structure of the Caribbean Netherlands' is aware that people have different expectations of the evaluation. There is some level of scepticism. Some people assume that the results of the evaluation will lead to yet another report, which will not have a considerable contribution to the, in their eyes, necessary change. Other people's expectations of the evaluation are high and they expect the results of the evaluation to lead to a new moment or a relaunch for further agreements that will mark the beginning of necessary changes. In any case, five years is too short a period to be able to give a final assessment of the new political structure. However, five years is an opportune period of time to be able to take stock of the situation and identify successes and elements that need improving. Add to this the fact that the results of the evaluation have been repeatedly identified as the cause for making new agreements. -

2013 Geelhoed Et Al Important Bird Areas in the Caribbean Netherlands

Important Bird Areas in the Caribbean Netherlands SCV Geelhoed, AO Debrot, JC Ligon, H Madden, JP Verdaat, SR Williams & K Wulf Report number C054/13 IMARES Wageningen UR Institute for Marine Resources & Ecosystem Studies Client: Ministry of Economic Affairs (EZ) Contact: Drs. H. Haanstra P.O. Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague BO-11-011.05-016 Publication date: 6 May 2013 IMARES is: an independent, objective and authoritative institute that provides knowledge necessary for an integrated sustainable protection, exploitation and spatial use of the sea and coastal zones; an institute that provides knowledge necessary for an integrated sustainable protection, exploitation and spatial use of the sea and coastal zones; a key, proactive player in national and international marine networks (including ICES and EFARO). P.O. Box 68 P.O. Box 77 P.O. Box 57 P.O. Box 167 1970 AB Ijmuiden 4400 AB Yerseke 1780 AB Den Helder 1790 AD Den Burg Texel Phone: +31 (0)317 48 09 00 Phone: +31 (0)317 48 09 00 Phone: +31 (0)317 48 09 00 Phone: +31 (0)317 48 09 00 Fax: +31 (0)317 48 73 26 Fax: +31 (0)317 48 73 59 Fax: +31 (0)223 63 06 87 Fax: +31 (0)317 48 73 62 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] www.imares.wur.nl www.imares.wur.nl www.imares.wur.nl www.imares.wur.nl Cover photo: Red-billed Tropicbird, Great Bay Sint Eustatius December 2012 (Steve Geelhoed) © 2013 IMARES Wageningen UR IMARES, institute of Stichting DLO The Management of IMARES is not responsible for resulting is registered in the Dutch trade damage, as well as for damage resulting from the application of Record nr. -

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Guidelines for Marine MPAs are needed in all parts of the world – but it is vital to get the support Protected Areas of local communities Edited and coordinated by Graeme Kelleher Adrian Phillips, Series Editor IUCN Protected Areas Programme IUCN Publications Services Unit Rue Mauverney 28 219c Huntingdon Road CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK Tel: + 41 22 999 00 01 Tel: + 44 1223 277894 Fax: + 41 22 999 00 15 Fax: + 44 1223 277175 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 3 IUCN The World Conservation Union The World Conservation Union CZM-Centre These Guidelines are designed to be used in association with other publications which cover relevant subjects in greater detail. In particular, users are encouraged to refer to the following: Case studies of MPAs and their Volume 8, No 2 of PARKS magazine (1998) contributions to fisheries Existing MPAs and priorities for A Global Representative System of Marine establishment and management Protected Areas, edited by Graeme Kelleher, Chris Bleakley and Sue Wells. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, The World Bank, and IUCN. 4 vols. 1995 Planning and managing MPAs Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers, edited by R.V. Salm and J.R. Clark. IUCN, 1984. Integrated ecosystem management The Contributions of Science to Integrated Coastal Management. GESAMP, 1996 Systems design of protected areas National System Planning for Protected Areas, by Adrian G. Davey. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. -

Coral Reef Resilience Assessment of the Bonaire National Marine Park, Netherlands Antilles

Coral Reef Resilience Assessment of the Bonaire National Marine Park, Netherlands Antilles Surveys from 31 May to 7 June, 2009 IUCN Climate Change and Coral Reefs Working Group About IUCN ,8&1,QWHUQDWLRQDO8QLRQIRU&RQVHUYDWLRQRI1DWXUHKHOSVWKHZRUOG¿QGSUDJPDWLFVROXWLRQVWRRXUPRVWSUHVVLQJ environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting VFLHQWL¿FUHVHDUFKPDQDJLQJ¿HOGSURMHFWVDOORYHUWKHZRUOGDQGEULQJLQJJRYHUQPHQWV1*2VWKH81DQGFRPSD- nies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. ,8&1LVWKHZRUOG¶VROGHVWDQGODUJHVWJOREDOHQYLURQPHQWDORUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKPRUHWKDQJRYHUQPHQWDQG1*2 members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in RI¿FHVDQGKXQGUHGVRISDUWQHUVLQSXEOLF1*2DQGSULYDWHVHFWRUVDURXQGWKHZRUOG www.iucn.org IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme The IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme (GMPP) provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the ,8&1DFWLYLWLHVWKDWGHDOZLWKPDULQHDQGSRODULVVXHVLQFOXGLQJSURMHFWVDQGLQLWLDWLYHVRIWKH5HJLRQDORI¿FHVDQGWKH ,8&1&RPPLVVLRQV*033ZRUNVRQLVVXHVVXFKDVLQWHJUDWHGFRDVWDODQGPDULQHPDQDJHPHQW¿VKHULHVPDULQH protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and the protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. -

Eyre Peninsula Visitation Snapshot

Eyre Peninsula National parks visitation snapshot The region South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula is the ultimate coastal getaway – but without the coastal crowds. The opportunity It boasts more than 2,000 kilometres of coastline stretching from the tip of Spencer Gulf 300km northwest of Adelaide through to the Eyre Peninsula’s regional strategy is to capitalise on its Great Australian Bight in the state’s west. pristine nature, immersive wildlife experiences and coastal lifestyle to drive increased overnight stays from Eyre Peninsula is known for its quality seafood, scenic national parks, international and domestic visitors. productive farmland, pounding surf and adventure activities, like shark cage diving and swimming with sea lions. Tourism In 2018, Eyre Peninsula contributed $310 million to SA’s $6.8 billion tourism expenditure. The region attracts approximately 212,000 overnight visitors per year (2016-18) – with almost three quarters being intrastate visitors. Of these, about half are from Adelaide and its surrounds, and the remainder from regional areas of the state. Eyre Peninsula has more than 26 visitor accommodation* options, totalling 987 available rooms. Over the course of a year, occupancy rates average at about 50 per cent – peaking at 52-53 per cent from September to November and 50-52 per cent from February to April, and dipping to 48 per cent in the winter months. For more in-depth analysis, view the SA Tourism Commission regional profiles *Hotels, motels and service apartments with 15+ rooms Monthly occupancy rates 2015-16 Length of visit to Eyre Peninsula National parks Eyre Peninsula’s national parks are one of the region’s main drawcards.