John Farley (D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2019), No. 3 1 the Story of One Year in the Early Life of New College

The Story of One Year in the Early Life of New College Introduction This article is based upon a New College Account Roll, which is in New College Archives1, covering the fifty-two weeks from 27 September 1392 to 26 September 1393. It comprises 422 items of income and expenditure and these have been numbered to allow reference in this article to those items in the associated transcript and translation documents which accompany this article. This is the first of the surviving annual New College Account Rolls to have been fully transcribed and translated and enables this ‘story’ of one year in the early life of the College to be told. The transcribed and translated text for selected items has been used as the basis of this ‘story’ (shown in blue). This New College Account Roll has been augmented by reference to other contemporary documents so that a fuller picture can be painted. The most important of these is the Hall Steward’s Book2 which contains the names of Fellows, Scholars, Chaplains and Visitors who attended the two daily meals in the Great Hall and it identifies the days when they left and rejoined the college during periods of absence. Another is the only surviving Household Account Roll for bishop William of Wykeham; it is held in Winchester College Muniments and has recently been transcribed and translated by this author3. The dates of all three manuscripts overlap and contain interrelated items concerning New College. The New College Account Rolls4 had been produced by the Warden, but, since a Statute revision in 13895, this was changed to be produced by three college Bursars who were elected each year. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91

The Register' of Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91 WILLIAM J. CONNOR This paper‘ seeks to show how the register dompiled for Robert Stillington, for twenty-five years bishop of Bath and Wells in the late fifteenth century, contributes to the understanding of the decoration of administrative documents in this period. It was largely compiled under the supervision of Hugh Sugar who, as vicar-general, was responsible for much of the routine administration of the diocese. He evidently encouraged the pen work embellishments, which are such a striking feature of this volume, and seems to have employed an artist whose only other known work appears in manuscripts commissioned by the previous bishop, Thomas Beckington. This links Stillington’s register directly to the academic elite of Winchester and New College, Oxford, and the culture of the Yorkist court. _ Dubbed re ”mumz': éué‘que by his French contemporary, Philippe de Commines,2 Robert Stillington enjoyed a colourful career. Probably born in Yorkshire c. 1410, he first appears in the records as a doctor of civil law at Oxford in 1443, by which time he was also a proctor of Lincoln College and principal of Deep Hall. At thispoint, probably already in his thirties, he embarked on the official and ecclesiastical career for which he is now remembered. A protégée of Thomas Beckington, the recently consecrated bishop of Bath and Wells, he was appointed as Beckington’s chancellor and to a prebend in Wells Cathedral in 1445, but not: ordained priest there until 1447. We then find him on a diplomatic mission to Burgundy in 1448 and as a royal councillor a year later. -

Cp40no1139cty.Pdf

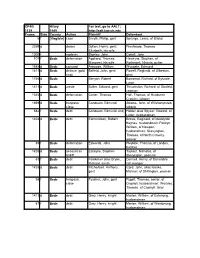

CP40/ Hilary For text, go to AALT: 1139 1549 http://aalt.law.uh.edu Frame Side County Action Plaintiff Defendant 5 f [illegible] case Smyth, Phillip, gent Sprynge, Lewis, of Bristol 2259 d dower Dyllon, Henry, gent; Prestwode, Thomas Elizabeth, his wife 1000 f replevin Stonley, John Cottell, John 101 f Beds defamation Appliard, Thomas; Hawkyns, Stephen, of Margaret, his wife Rothewell, Nhants, pulter 1685 d Beds concord Atwoode, William Wyngate, Edmund 1411 d Beds detinue (gold Belfeld, John, gent Powell, Reginald, of Olbeston, ring) gent 1746 d Beds Benyon, Robert Bowstrad, Richard, of Byscote, Luton 1411 d Beds waste Butler, Edward, gent Thruckston, Richard, of Stotfeld, yeoman 1345 d Beds defamation Carter, Thomas Hall, Thomas, of Husburne Crawley, laborer 1869 d Beds trespass: Conquest, Edmund Adams, John, of Wilshampsted, close laborer 582 f Beds debt Conquest, Edmund, esq Helder alias Spycer, Edward, of Luton, husbandman 1428 d Beds debt Edmundson, Robert Browe, Reginald, of Meddylton Keynes, husbandman; Pokkyn, William, of Newport, husbandman; Skevyngton, Thomas, of North Crawley, weaver 85 f Beds defamation Edwards, John Pleyfote, Thomas, of London, butcher 1426 d Beds account as Estwyke, Stephen Taylour, Nicholas, of bailiff Stevyngton, yeoman 83 f Beds debt Fawkener alias Bryan, Dennell, Henry, of Dunstable, Richard, smith fish monger 1428 d Beds debt Fitzherbart, Anthony, Izard, John, alias Isaake, gent Michael, of Shitlington, yeoman 98 f Beds trespass: Fyssher, John, gent Pygett, Thomas, senior, of close Clophyll, husbandman; -

Historical Collections Relating to Chiswick

— * •- . W. PHILL1M0RE AND W. H. WHITEAR ^cu/id ©• JMKay S£d>Aany USRB For Reference Not to be taken from this room CHISWICK. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/historicalcollecOOphil : ' HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS RELATING TO CHISWICK EDITED BY W. P. W. PHILLIMORE AND W. H. WHITEAR. LONDON Phillimore & Co Essex Street, Strand. , 36, 1897. NOTE. THIS volume is an attempt to collect together in a handy form some historical information relating to the parish of Chiswick. It originated in some weekly contributions sent by the Editors to a local newspaper, the " Chiswick Times," during the years 1895 an^ 1896. This serves to explain the fact that the book is more a collection of essays than a systematic parochial history, though all the same it may be hoped that it will hereafter prove a useful groundwork to some one able and willing to compile a history worthy of the parish. Incomplete as the present work is, it will serve to direct attention to the many points of interest in the past history of Chiswick. Much still remains to be done, for as yet the public records have been but little drawn upon, and the reader must not think that we have at all exhausted the field of research which lies open to us. Some of the chapters are merely reprints from other works ; some are by one or other of the Editors ; for the chapter on Sutton Court the reader is indebted to Mr. W. M. Chute, and for the account of the prebendal manor to Mr. -

CONTEXTS of the CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume Ltext

CONTEXTS OF THE CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume LText. PAMELA MARGARET KING D. Phil. UNIVERSITY OF YORK CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES October, 1987. TABLE QE CONTENTS Volume I Abstract 1 List of Abbreviations 2 Introduction 3 I The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Problem Stated. 7 II The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Surviving Evidence. 57 III The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: Theological and Literary Background. 152 IV The Cadaver Tomb in England to 1460: The Clergy and the Laity. 198 V The Cadaver Tomb in England 1460-1480: The Clergy and the Laity. 301 VI The Cadaver Tomb in England 1480-1500: The Clergy and the Laity. 372 VII The Cadaver Tomb in Late Medieval England: Problems of Interpretation. 427 Conclusion 484 Appendix 1: Cadaver Tombs Elsewhere in the British Isles. 488 Appendix 2: The Identity of the Cadaver Tomb in York Minster. 494 Bibliography: i. Primary Sources: Unpublished 499 ii. Primary Sources: Published 501 iii. Secondary Sources. 506 Volume II Illustrations. TABU QE ILLUSTRATIONS Plates 2, 3, 6 and 23d are the reproduced by permission of the National Monuments Record; Plates 28a and b and Plate 50, by permission of the British Library; Plates 51, 52, 53, a and b, by permission of Trinity College, Cambridge. Plate 54 is taken from a copy of an engraving in the possession of the office of the Clerk of Works at Salisbury Cathedral. I am grateful to Kate Harris for Plates 19 and 45, to Peter Fairweather for Plate 36a, to Judith Prendergast for Plate 46, to David O'Connor for Plate 49, and to the late John Denmead for Plate 37b. -

Ball Family Records

BALL FAMILY RECORDS. BALL FAMILY RECORDS GENEALOGICAL MEMOIRS OF SOME BALL FAMILIES OF GREAT BRITAIN, IRELAND, AND AMERICA COMPILED BY THE REV. WILLIAM BALL WRIGHT, M.A. Late Brasinns 8,nilh Exhibitioner, Trin. Coll., Diiblin, l',,f,R.S.A.., Ireland, Author of "The Ussher Me,no-irs," and "Life Sketch of Archbishop Bramhall Second Edition, Enlarged and Revised YORK PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY THE YORKSHIRE PRINTING Co., LTD. 1908 To SIR ROBERT STA WELL BALL, F.R.S., Lowndes Professor o.f Astronomy, Cambridge University, and to the other bearers o.f the name o.f Ball who, in the past and present, have added lustre and distinction to thez·r name and .families by their scientific discoveries and writings, This Book o.f Ball Fam£ly Records at home and abroad is Dedicated by the Author. CONTENTS. PAGES Chapter I.-The origin and early mention the name of Ball 1-7 11.-The Ball Family of St. Audoen's Padsh, Dublin Ba!lygall, Co.Dublin, and Ballsgrove, Drogheda, ·with notices of the Ussher Fami!v. and of Bartholomew, Walter, Nicholas, R'obert and Edward Ball, Mayors of Dublin 8-54 IIJ.-'The Ball Family of Baldrumtnin, Parish of Lusk, Co. Dublin 55-56 lV.-The Balls of Co. Fermanagh, of Cookesto,vn, " Co. Meath, and of Philadelphia, with notices of the Connolly and Carleton Families, and of the Blackall Family - 57-72 V.-The Ball Family of Scottowe, and of the " Counties of Armagh and Kilkenny 73-94 VI.-The Ball Family of Ardee, Co. Louth, with notice of Sergeant John Ball, M.P. -

Sorted by Defendant

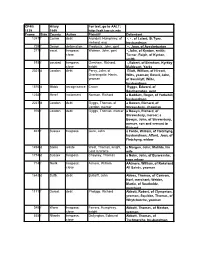

CP40/ Hilary For text, go to AALT: 1139 1549 http://aalt.law.uh.edu Frame Side County Action Plaintiff Defendant 1247 f Cornw debt Arundell, Humphrey, of -, - , of Lalant, St Tyes, Hellond, esq husbandman 729 f Devon defamation Predyaux, John, gent --, Joan, of Ayssheburton 277 f vacat trespass: Wolmer, John, gent -,John, of Kynton, smith; close Turner, Ralph, of Kynton, smith 193 f vacated trespass: Gresham, Richard, -,Robert, of Brimham, Kyrkby close knight Maldesert, Yorks 2021 d London debt Percy, John, of Eliott, William, of Hircott, Overbrigatte, Hants, Wilts, yeoman; Revell, John, yeoman of Swalclyff, Wilts, husbandman 1870 d Middx recognisance Crown Ryggs, Edward, of Southampton, gent 1238 f Heref incitement Norman, Richard a Baddam, Roger, of Yorkehill, husbandman 2227 d London debt Gyggs, Thomas, of a Bowen, Richard, of London, mercer Shrewsbury, chapman 976 f London debt Gyggs, Thomas, mercer a Bowyn, Richard, of Shrewsbury, mercer; a Bowyn, John, of Shrewsbury, mercer, son and servant to Richard 461 f Sussex trespass Gere, John a Forde, William, of Fletchyng, husbandman; Afford, Joan, of Fletchyng, widow 1494 d Soms waste West, Thomas, knight, a Morgan, John; Matilda, his Lord la Warre wife 1774 d Sussex trespass Cheyney, Thomas a Noke, John, of Burwasshe, rope mkaer 714 f Norfk trespass: Atmere, William AAtmere, William, of Rokeland close All Saints, yeoman 1643 d Suffk debt Buttolff, John Abbes, Thomas, of Cawson, Norf, merchant; Webbe, Martin, of Southolde, merchant 1171 f Dorset debt Phelypp, Richard Abbott, Robert, of -

For a Decent Order in the Church'

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL 'For a decent order in the Church': Ceremony, Culture and Conformity in an Early Stuart Diocese, with particular reference to the See of Winchester being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD by Peter Lawrence Abraham BA History/Music (Cardiff 1993) MA History (1995) August 2002. CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii Abbreviations and Conventions iv Introduction: Historiographical Background and Note on Sources 1 Prologue: The Diocese 17 PART ONE: Ceremony 55 Chapter One: The Externals of Worship 58 Chapter Two: The Liturgy 110 PART TWO: Culture 149 Chapter Three: The Visual Arts and the Use of Space 151 Chapter Four: The Aural Arts 193 Chapter Five: The 'Culture' of Puritanism 233 PART THREE: Conformity 267 Chapter Six: The Defence of Conformity 270 Chapter Seven: The Imposition of Conformity 298 Epilogue: Case Studies 341 Conclusion 373 Appendices 377 Bibliography 384 i ABSTRACT The title of this thesis is taken from the Book of Common Prayer, specifically from the section 'Of Ceremonies: Why some be Abolished and some Retained'. It takes as its premise the theory that arguments over the way in which worship was conducted were more important than doctrinal matters in the religious tensions which arose before the Civil War, focussing attention upon the diocese of Winchester. The thesis is split into three broad sections. The first section deals with the ceremonies of the church, and is split into two chapters. The first of these chapters is based largely around the physical structure of a church, whilst the second is more concerned with the rites and rubrics as laid down in the Book of Common Prayer. -

Religion & Theology | Subject Catalog (PDF)

Religion & Theology Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC018 -04 updated May 2010 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 2 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 3 Research Collections............................................................................................. 4 Manuscripts & Sacred Texts ............................................................................................................................5 Mission Collections ......................................................................................................................................... 17 Christianity ....................................................................................................................................................... 26 General Interest ............................................................................................................................................................ 26 Adventist ....................................................................................................................................................................... 32 Baptist ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

**April Pages.Indd

BISHINIK PRSRT STD P.O. Drawer 1210 U.S. Postage Paid Durant OK 74702 Durant OK RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED Permit #187 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE CHOCTAW NATION OF OKLAHOMA Serving 168,517 Choctaws Worldwide www.choctawnation.com April 2005 Issue Recovery Center celebrates with ribboncutting The Choctaw Nation has just opened the newly Center were at no cost to any Choctaw who has constructed Recovery Center in Talihina. The a need for the program. The tribe even provides Recovery Program is now able to offer services to transportation assistance to Talihina for Recovery 20 clients at the live-in program. Center clients. Prior to the ribboncutting, Ben Brown, Deputy The new Recovery Center has two nice exercise Director for the State of Oklahoma Substance rooms with equipment, a group room for men Abuse Program, complimented the Choctaw and a second group room for women, each with Recovery Program and facility, saying, “We televisions, personal living quarters shared by have nothing this nice in the State of Oklahoma.” two clients, counseling rooms and state-of-the-art Brown went on to say, “When you come to a kitchen and information technology departments. program like this, you see great things – miracles Darrell Sorrells, the Director of the Recovery happen, lives are restored and families are put Center, said that he and staff had visited other back together.” facilities prior to the final design to get opinions “We think of chemical dependence as a treatable on what worked well and what floor plans illness, and want to provide appropriate care so could be improved. -

New Studies in Medieval Culture

Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture ETHAN KNAPP, SERIES EDITOR Form and Reform Reading across the Fifteenth Century EDITED BY SHANNON GAYK AND KATHLEEN TONRY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS · COLUMBUS Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Form and reform : reading across the fifteenth century / edited by Shannon Gayk and Kathleen Tonry. p. cm. — (Interventions: new studies in medieval culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1163-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1163-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9264-8 (cd) 1. English literature—Middle English, 1100–1500—History and criticism. 2. Literary form— History—To 1500. I. Gayk, Shannon Noelle. II. Tonry, Kathleen Ann. III. Series: Interventions : new studies in medieval culture. PR293.F67 2011 820.9'002—dc22 2010053790 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1163-2) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9264-8) Cover design by Laurence Nozik Type set in Times New Roman Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents List of Illustrations vii List of Abbreviations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: The “Sotil Fourmes” of the Fifteenth Century KATHLEEN TONRY 1 PART 1. THE MATERIALS OF FORM 1 Forms of Reading in the Book of Brome JESSICA BRANTLEY 19 2 The Style of Humanist Latin Letters at the University of Oxford: On Thomas Chaundler and the Epistolae Academicae Oxon.