New Studies in Medieval Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

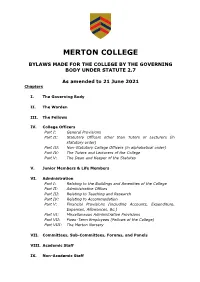

Merton College Bylaws As at 2021-06-21

MERTON COLLEGE BYLAWS MADE FOR THE COLLEGE BY THE GOVERNING BODY UNDER STATUTE 2.7 As amended to 21 June 2021 Chapters I. The Governing Body II. The Warden III. The Fellows IV. College Officers Part I: General Provisions Part II: Statutory Officers other than Tutors or Lecturers (in statutory order) Part III: Non-Statutory College Officers (in alphabetical order) Part IV: The Tutors and Lecturers of the College Part V: The Dean and Keeper of the Statutes V. Junior Members & Life Members VI. Administration Part I: Relating to the Buildings and Amenities of the College Part II: Administrative Offices Part III: Relating to Teaching and Research Part IV: Relating to Accommodation Part V: Financial Provisions (including Accounts, Expenditure, Expenses, Allowances, &c.) Part VI: Miscellaneous Administrative Provisions Part VII: Fixed-Term Employees (Fellows of the College) Part VIII: The Merton Nursery VII. Committees, Sub-Committees, Forums, and Panels VIII. Academic Staff IX. Non-Academic Staff X. The Common Table, The Common Room, College Dinners and Entertainment Part I: The Common Room Part II: The Common Table Part III: College Dinners and Entertainment XI. Discipline and Fitness to Study of Junior Members XI A: Academic Discipline XI B: Discipline for Serious Misconduct XI C: Failure in the First Public Examination XI D: Suspension and Fitness to Study Appendices A. Bylaw VI.1(b): Commemoration of Benefactors B. Bylaw VI.39: Policies adopted by the Governing Body 1. EJRA Policy 2012 2. Information Security a. Information Security Policy 2018 b. Data Protection Policy 2018 c. Data Protection Breach Regulations 2018 d. Mobile Device Security Regulations 2018 e. -

Diction and Syntax in Web 2.0 Text

Diction and Syntax in Web 2.0 text Narantsogt Baatarkhuu Bachelor Thesis 2009 ***scanned submission page 1*** ***scanned submission page 2*** ABSTRAKT Czech abstract Narůstající důležitost internetu v běžném životě způsobuje, že každý den je přenášeno a zpracováváno obrovské množství informací. Předložená bakalářská práce prezentuje koncepci a charakteristiku angličtiny jako lingua franca na nové World Wide Web, jmenovitě výběr lexika a strukturu vět často používaných na Web 2.0. Teoretická část zkoumá tři koncepty dikce, syntaxe a Webu 2.0; tyto koncepty jsou studovány z pohledu pozadí a vzájemných vztahů. Analytická část rozebírá několik významných webových stránek/aplikací z pohledu dikce a syntaxe. Výsledky analýzy jsou porovnány a v závěru jsou uvedeny společné rysy těchto stránek. Klíčová slova: dikce, syntax, Web 2.0, internet, webova stranky, Anglisticky stylistika. ABSTRACT English abstract As the Internet’s role in our lifestyle increases, massive amount of information is being generated, exchanged and processed every day. This paper tries to conceptualize the characteristics of English language as a lingua franca of the “new” World Wide Web, especially the choice of words and the sentence structures frequently used in the “Web 2.0”. The theoretical part explores the three concepts of diction, syntax and Web 2.0, and each concept’s background and interrelations are studied. In the analysis section, few major websites/applications are analyzed of their diction and syntax. Consequently, the analysis results are compared, and finally the common features will be found for conclusion. Keywords: diction, syntax, web 2.0, web applications, English stylistics. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Mr.Chernel and Dr.Lengalova all the things they taught me, all the times they motivated me and consulted me, even when I was irresponsible. -

The Aureate Terms Ln the Post-Chaucerian Period

_J 1 The Aureate Terms ln the Post-Chaucerian Period :I Ayako Kobayashi ( 'l'=~* -~-~ ) I The first use·of the term 11 aureate tongis11 applied to literary style is found in the poem of William Dunbar who is one o.f the representatives of the Scottish Chaucerians ~1 The adject-ive naureate" had been used by John. Lydgate in his TPoy Book ( c .1420 MED) and py Oswald Gabelkhover in The Boock of Physieke (1599 OED), but it was used as an attribute to a tlrlng "lycoure" and "water11 respectively. Dunbar, on the other , hand, used it not only to denote the brilliancy or splendid- . ness of literary skill in poetry but was completely aware of the importance of it as his poem in which he invokes Homer and ~~ Cicero to help his pen shows: ~ I Discrive I wald, bot quho coud wele endyte ~ . I Noucht ·thou, Orner, ·als fair as thou coud wryte, ·For· ail ·.thine ornate stilis so perfyte; Nor yit thou, Tullius, quhois lippis suete Off rethorike did in to termes flete: Your aureate tongis both bene all to lyte, For to compile that paradise complete. The Go ldyn Ta:Pge 11. 64-72 Important though it was for Dunbar in the early fif teenth century, •.the concept! of aureation is difficult to define. There were many ways to express the lexical ornamentation of that age. Vere L. Rubel gives twelve different modifiers equivalent to 11 aureate" language: ornate,· laureate, high and curious, silver, garnished, pullysh~d, artamalit~ embellished, fructuous, facundyous, sugurit and mellifluate.~ William Geddie complains that the phrase "ornate style," 11 flood of "' eloquence" and the like are applied·quite indiscriminately. -

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms CHRIS BALDICK OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD PAPERBACK REFERENCE The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms Chris Baldick is Professor of English at Goldsmiths' College, University of London. He edited The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales (1992), and is the author of In Frankenstein's Shadow (1987), Criticism and Literary Theory 1890 to the Present (1996), and other works of literary history. He has edited, with Rob Morrison, Tales of Terror from Blackwood's Magazine, and The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, and has written an introduction to Charles Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer (all available in the Oxford World's Classics series). The most authoritative and up-to-date reference books for both students and the general reader. Abbreviations Literary Terms Oxford ABC of Music Local and Family History Paperback Accounting London Place Names* Archaeology* Mathematics Reference Architecture Medical Art and Artists Medicines Art Terms* Modern Design* Astronomy Modern Quotations Better Wordpower Modern Slang Bible Music Biology Nursing Buddhism* Opera Business Paperback Encyclopedia Card Games Philosophy Chemistry Physics Christian Church Plant-Lore Classical Literature Plant Sciences Classical Mythology* Political Biography Colour Medical Political Quotations Computing Politics Dance* Popes Dates Proverbs Earth Sciences Psychology* Ecology Quotations Economics Sailing Terms Engineering* Saints English Etymology Science English Folklore* Scientists English Grammar Shakespeare English -

29 02 16 Leahy on Douglas.03

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository 1 Dreamscape into Landscape in Gavin Douglas CONOR LEAHY More than any other poet of the late Middle Ages Gavin Douglas knew how to describe the wind. It could have a ‘lowde quhissilling’ or a ‘softe piping’; could blow in ‘bubbys thik’ or ‘brethfull blastis’. Its rumbling ‘ventositeis’ could be ‘busteous’ or ‘swyft’ or ‘swouchand’. On the open water, it could ‘dyng’ or ‘swak’ or ‘quhirl’ around a ship; could come ‘thuddand doun’ or ‘brayand’ or ‘wysnand’. At times it could have a ‘confortabill inspiratioun’, and nourish the fields, but more typically it could serve as a harsh leveller, ‘Dasyng the blude in euery creatur’.1 Such winds are whipped up across the landscapes and dreamscapes of Douglas’s surviving poetry, and attest to the extraordinary copiousness of his naturalism. The alliterative tradition was alive and well in sixteenth century Scotland, but as Douglas himself explained, he could also call upon ‘Sum bastard Latyn, French or Inglys’ usages to further enrich ‘the langage of Scottis natioun’.2 Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1513) has itself occasioned a few blasts of hot air. John Ruskin described it as ‘one of the most glorious books ever written by any nation in any language’ and would often mention Douglas in the same breath as Dante.3 Ezra Pound breezily declared that the Eneados was ‘better than the original, as Douglas had heard the sea’,4 while T.S. -

John Farley (D

John Farley (d. 1464) and the Finessing of MS 281 In spite of having suffered the loss of three illuminated leaves, MS 281 in the College Library remains a refined object. It contains a copy of Ptolemy’s Almagesta in the translation of Gerard of Cremona, written in England in a steady gothic bookhand, for which a date around the third quarter of the thirteenth century may be suggested. Ample margins were left open for the text’s diagrams and tables, which are mostly present, and there is quite an extensive, coeval gloss. Space was also left for decorated initials—but artists for these were not found until nearly two centuries later. When a date for the manuscript has been suggested in the scholarly literature, the tension between the script and the illumination, both pulling in opposite directions, has led opinion to cluster somewhere in the middle. Coxe, in what was the first published description of the manuscript, suggested that it belonged to the late fourteenth century (‘s. xiv exeuntis’).1 Dates have been offered in more recent times by scholars whose interest was the text itself: Paul Kunitzsch (‘14. Jh.’), followed by Henry Zepeda (‘fourteenth century’), and David Juste (‘s. xiv’).2 Richard Hunt had in fact already spotted that the script and decoration belong to different periods, in his essay in the College’s sexcentenary volume.3 Both text and decoration have distinct interest. The marginal apparatus, added in a small Anglicana hand not long after the main scribe’s work, presents as a gloss on the text excerpts taken from Almagesti minor.4 Zepeda noted that our manuscript shares a close connection in these notes with one other copy, in the Laurentian Library in Florence, MS Plut. -

Othering Poetic Form Through Translation

Amanda French Conference -- Art Both Ways: Translation, Restoration, and Re-creation American Literary Translators Association Panel -- Making it Auld: Translation and Philology Saturday, October 30, 2004 The Othering of Poetic Form Through Translation: Jean Passerat's "J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle" (1574) As the first villanelle, Jean Passerat's "J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle" (1574) is historically important for a number of reasons, among them the fact that contemporary Anglophone poems from Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night" to Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art" and beyond have adopted and explored its form. I have found seven English verse translations of the poem, the first in 1906, all of which indicate a vested interest in keeping the poem historically "othered" through the use of archaic language. Archaic language for archaic works was de rigueur in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, but since the modern fashion of translation is to render a work that seemed fresh and colloquial in its own day in language that seems fresh and colloquial to us, it is therefore interesting that translators of "J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle" resisted the trend of translation theory, continuing to render the poem in archaic language. I would argue that Passerat's poem has been othered in English translation so as to keep the idea of fixed poetic form strictly marginal in contemporary Anglophone poetry. Most of those involved with contemporary American poetry are aware that there has been a recent surge of interest in the villanelle. The timing of this revival suggests that it is partly due to Elizabeth Bishop's villanelle "One Art," which was first published 2 in the New Yorker in 1976 and also appeared that same year in her influential collection Geography III. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

E New Modernist Studies: What's Left of Political Formalism?

Max Brzezinski !e New Modernist Studies: What’s Left of Political Formalism? In their 2008 PMLA article “!e New Modernist Studies,” Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. Walkowitz simultaneously chart and promote the development of the New Modernist Studies (NMS), a critical movement of which they are the leading spokespeople and practi tion- ers. In the beginning of their piece, Mao and Walkowitz announce that “[w]ere one seeking a single word to sum up transformations in modern literary scholarship over the past decade or two, one could do worse than light on expansion” (737; emphasis in original). !ey then go on to specify the signi"cance of these transformations for the study of modernism and modernity, honing in on what they call the NMS’s “spatial” and “vertical” expansion. By spatial expansion, they mean NMS critics’ move away from national traditions toward conceptu- alizations of transnational ones; by vertical expansion, a parallel move away from modernist elitism toward a pluralistic opening up of crit- icism to popular culture, “works by marginalized social groups,” and a new focus on “matters of production, dissemination, and reception” (738). Given that these critics claim new interest in the way institu- tional and empirical economic contexts have shaped modernist works, the time is nigh to consider how and why the work of the NMS has emerged out of our contemporary economic, political, and institu- tional academic situation. By doing so below, I politicize and extend Jennifer Wicke’s prescient (2001) suggestion that “[a]s revivers of its brand [modernism], a brand we cannot seem to do without, we re- brand ourselves as critics and theorists just as we rebrand modernist others” (395). -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

Refrain, Again: the Return of the Villanelle

Refrain, Again: The Return of the Villanelle Amanda Lowry French Charlottesville, VA B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992, cum laude M.A., Concentration in Women's Studies, University of Virginia, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August 2004 ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ABSTRACT Poets and scholars are all wrong about the villanelle. While most reference texts teach that the villanelle's nineteen-line alternating-refrain form was codified in the Renaissance, the scholar Julie Kane has conclusively shown that Jean Passerat's "Villanelle" ("J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle"), written in 1574 and first published in 1606, is the only Renaissance example of this form. My own research has discovered that the nineteenth-century "revival" of the villanelle stems from an 1844 treatise by a little- known French Romantic poet-critic named Wilhelm Ténint. My study traces the villanelle first from its highly mythologized origin in the humanism of Renaissance France to its deployment in French post-Romantic and English Parnassian and Decadent verse, then from its bare survival in the period of high modernism to its minor revival by mid-century modernists, concluding with its prominence in the polyvocal culture wars of Anglophone poetry ever since Elizabeth Bishop’s "One Art" (1976). The villanelle might justly be called the only fixed form of contemporary invention in English; contemporary poets may be attracted to the form because it connotes tradition without bearing the burden of tradition. Poets and scholars have neither wanted nor needed to know that the villanelle is not an archaic, foreign form. -

Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91

The Register' of Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91 WILLIAM J. CONNOR This paper‘ seeks to show how the register dompiled for Robert Stillington, for twenty-five years bishop of Bath and Wells in the late fifteenth century, contributes to the understanding of the decoration of administrative documents in this period. It was largely compiled under the supervision of Hugh Sugar who, as vicar-general, was responsible for much of the routine administration of the diocese. He evidently encouraged the pen work embellishments, which are such a striking feature of this volume, and seems to have employed an artist whose only other known work appears in manuscripts commissioned by the previous bishop, Thomas Beckington. This links Stillington’s register directly to the academic elite of Winchester and New College, Oxford, and the culture of the Yorkist court. _ Dubbed re ”mumz': éué‘que by his French contemporary, Philippe de Commines,2 Robert Stillington enjoyed a colourful career. Probably born in Yorkshire c. 1410, he first appears in the records as a doctor of civil law at Oxford in 1443, by which time he was also a proctor of Lincoln College and principal of Deep Hall. At thispoint, probably already in his thirties, he embarked on the official and ecclesiastical career for which he is now remembered. A protégée of Thomas Beckington, the recently consecrated bishop of Bath and Wells, he was appointed as Beckington’s chancellor and to a prebend in Wells Cathedral in 1445, but not: ordained priest there until 1447. We then find him on a diplomatic mission to Burgundy in 1448 and as a royal councillor a year later.