Settling the London Tithe Debates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREEK SOURCES of the COMPLUTENSIAN POLYGLOT Natalio Fernández Marcos Centro De Ciencias Humanas Y Sociales. CSIC. Madrid In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC GREEK SOURCES OF THE COMPLUTENSIAN POLYGLOT Natalio Fernández Marcos Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales. CSIC. Madrid In the Grinfield Lectures 2003 devoted to The Study of the Septuagint in Early Modern Europe Prof. Scott Mandelbrote deals, among other interesting issues, with the text of the Alcalá Polyglot, the earliest printed text of the Septuagint completed the 10th July 1517. He pointed out the impact of the arrival of Codex Alexandrinus in England in 1627 and its use as one of the main authorities for the London Polyglot (1653–1657), whose editor, Brian Walton, was especially critical of the text of the Complutensian Polyglot and the precise age of the manuscripts on which it had been based.1 Indeed, Walton’s judgement is highly negative; he maintains that the Greek text of the Alcalá Polyglot is very far from the genuine Septuagint. It is a compilation of several different texts with Hexaplaric additions and even Greek commentaries in an attempt to relate it to the Hebrew text printed in the parallel column.2 He backs up his statement with some examples taken from the first chapter of the book of Job. Since then the vexed problem of the Greek manuscripts used by the Complutensian philologists has been dealt with by different scholars, including myself. However, I think it is worthwhile taking another look at the question in the light of new evidence which has recently been published in the context of Septuagint textual criticism. -

Investment in the East India Company

The University of Manchester Research The Global Interests of London's Commercial Community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company DOI: 10.1111/ehr.12665 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Smith, E. (2018). The Global Interests of London's Commercial Community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company. The Economic History Review, 71(4), 1118-1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12665 Published in: The Economic History Review Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:05. Oct. 2021 The global interests of London’s commercial community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company The English East India Company (EIC) has long been identified as an organisation that foreshadowed developments in finance, investment and overseas expansion that would come to fruition over the course of the following two centuries. -

JAMES USSHER Copyright Material: Irish Manuscripts Commission

U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page i The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER Copyright material: Irish Manuscripts Commission Commission Manuscripts Irish material: Copyright U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iii The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER 1600–1656 V O L U M E I I I 1640–1656 Commission Letters no. 475–680 editedManuscripts by Elizabethanne Boran Irish with Latin and Greek translations by David Money material: Copyright IRISH MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION 2015 U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iv For Gertie, Orla and Rosemary — one each. Published by Irish Manuscripts Commission 45 Merrion Square Dublin 2 Ireland www.irishmanuscripts.ie Commission Copyright © Irish Manuscripts Commission 2015 Elizabethanne Boran has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000, Section 107. Manuscripts ISBN 978-1-874280-89-7 (3 volume set) Irish No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. The index was completed with the support of the Arts andmaterial: Social Sciences Benefaction Fund, Trinity College, Dublin. Copyright Typeset by December Publications in Adobe Garamond and Times New Roman Printed by Brunswick Press Index prepared by Steve Flanders U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page v S E R I E S C O N T E N T S V O L U M E I Abbreviations xxv Acknowledgements xxix Introduction xxxi Correspondence of James Ussher: Letters no. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

116 Seventeenth-Century News

116 seventeenth-century news College. Milton soon readies himself to express “some naked thoughts that rove about / And loudly knock to have their passage out” (quoted in Prawdzik 27). This stage performance, Prawdzik explains, feminizes the poet (31) and thereby places him in a transsexual subject posi- tion (32), one that arises from the “ambiguous intertwining of flesh and the forces [of desire] that move it” (33). The public spectacle of the poet’s transsexual body threatens his identity even as it lends him authorial power: Milton locates the menace that attends theatricality in the genitals themselves, the epicentre of the possibly exposed. As the source of reproductive power and as the anchor of gendered identity, they are, as well, a sign of poetic authority. In the ne- gotiations of the theatricalised rhetorical situation, the genitals are a locus of shape-shifting and of potential castration. (35) Those of us who are unable to find any genitals in this early poem might question Prawdzik’s analysis, but we can still learn much from him about Milton’s struggle to negotiate his identity under the “hostile gaze felt to issue from a social body, a panoptic God, or the conscience or superego” (35). This is the work of a bold scholar, willing to take imaginative risks, and eager to bring Milton into new realms of literary criticism and theory that have too often left him behind. J. Caitlin Finlayson & Amrita Sen, eds. Civic Performance: Pagentry and Entertainments in Early Modern England. London & New York: Routledge, 2020. xiv + 254 pp. 8 illustrations. -

Satirical Legal Studies: from the Legists to the Lizard

Michigan Law Review Volume 103 Issue 3 2004 Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard Peter Goodrich Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Peter Goodrich, Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard, 103 MICH. L. REV. 397 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol103/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SATIRICAL LEGAL STUDIES: FROM THE LEGISTS TO THE LIZARD Peter Goodrich* ANALYTICAL TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................... .............................................. ........ .... ..... ..... 399 I. FRAGMENTA ANTIQUITATIS (THE ENDURING TRADITION) .. 415 A. The Civilian Tradition .......................................................... 416 B. The Sermon on the Laws ......................... ............................. 419 C. Satirical Themes ....................... ............................................. 422 1. Personification .... ............................................................. 422 2. Novelty ....................................... -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

Title Page R.J. Pederson

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22159 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Pederson, Randall James Title: Unity in diversity : English puritans and the puritan reformation, 1603-1689 Issue Date: 2013-11-07 Chapter 3 John Downame (1571-1652) 3.1 Introduction John Downame (or Downham) was one of the greatest exponents of the precisianist strain within Puritanism during the pre-revolutionary years of the seventeenth century, a prominent member of London Puritanism, and renowned casuist.1 His fame rests chiefly in his nineteen published works, most of which were works of practical divinity, such as his four-part magnum opus, The Christian Warfare (1604-18), and his A Guide to Godlynesse (1622), a shorter, though still copious, manual for Christian living. Downame was also known for his role in publishing two of the most popular theological manuals: Sir Henry Finch’s The Summe of Sacred Divinitie (1620), which consisted of a much more expanded version of Finch’s earlier Sacred Doctrine (1613), and Archbishop James Ussher’s A Body of Divinitie (1645), which was published from rough manuscripts and without Ussher’s consent, having been intended for private use.2 Downame also had a role in codifying the Westminster annotations on the Bible, being one of a few city ministers to work on the project, though he never sat at the Westminster Assembly.3 Downame’s older brother, 1 Various historians from the seventeenth century to the present have spelled Downame’s name differently (either Downame or Downham). The majority of seventeenth century printed works, however, use “Downame.” I here follow that practice. -

EB WARD Diary

THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE Transcribed and prepared by Dr. M.M. Knappen, Professor of English History, University of Chicago. Edited by John W. Cowart Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE. Copyright © 2007 by John W. Cowart. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Lulu Press. Apart from reasonable fair use practices, no part of this book’s text may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bluefish Books, 2805 Ernest St., Jacksonville, Florida, 32205. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data has been applied for. Lulu Press # 1009823. Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info SAMUEL WARD 1572 — 1643 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………..…. 1 THE TWO SAMUEL WARDS……………………. …... 13 SAMUEL WARD’S LISTIING IN THE DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY…. …. 17 DR. M.M. KNAPPEN’S PREFACE ………. …………. 21 THE PURITAN CHARACTER IN THE DIARY. ….. 27 DR. KNAPPEN’S LIFE OF SAMUEL WARD …. …... 43 THE DIARY TEXT …………………………….……… 59 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ DEDICATION TO THE KING……………………………………….… 97 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE TO BIBLE READERS ………………………………………….….. 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………….…….. 129 INTRODUCTION by John W. Cowart amuel Ward, a moderate Puritan minister, lived from 1572 to S1643. His life spanned from the reign of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, through that of King James. and into the days of Charles I. Surviving pages of Ward’s dated diary entries run from May 11, 1595, to July 1, 1632. -

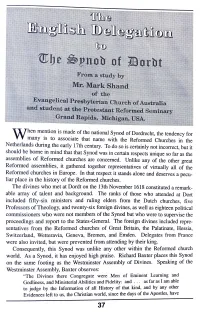

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

How English Baptists Changed the Early Modern Toleration Debate

RADICALLY [IN]TOLERANT: HOW ENGLISH BAPTISTS CHANGED THE EARLY MODERN TOLERATION DEBATE Caleb Morell Dr. Amy Leonard Dr. Jo Ann Moran Cruz This research was undertaken under the auspices of Georgetown University and was submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in History at Georgetown University. MAY 2016 I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. ABSTRACT The argument of this thesis is that the contrasting visions of church, state, and religious toleration among the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists in seventeenth-century England, can best be explained only in terms of their differences over Covenant Theology. That is, their disagreements on the ecclesiological and political levels were rooted in more fundamental disagreements over the nature of and relationship between the biblical covenants. The Baptists developed a Covenant Theology that diverged from the dominant Reformed model of the time in order to justify their practice of believer’s baptism. This precluded the possibility of a national church by making baptism, upon profession of faith, the chief pre- requisite for inclusion in the covenant community of the church. Church membership would be conferred not upon birth but re-birth, thereby severing the links between infant baptism, church membership, and the nation. Furthermore, Baptist Covenant Theology undermined the dominating arguments for state-sponsored religious persecution, which relied upon Old Testament precedents and the laws given to kings of Israel. These practices, the Baptists argued, solely applied to Israel in the Old Testament in a unique way that was not applicable to any other nation. Rather in the New Testament age, Christ has willed for his kingdom to go forth not by the power of the sword but through the preaching of the Word. -

The 1641 Lords' Subcommittee on Religious Innovation

A “Theological Junto”: the 1641 Lords’ subcommittee on religious innovation Introduction During the spring of 1641, a series of meetings took place at Westminster, between a handful of prominent Puritan ministers and several of their Conformist counterparts. Officially, these men were merely acting as theological advisers to a House of Lords committee: but both the significance, and the missed potential, of their meetings was recognised by contemporary commentators and has been underlined in recent scholarship. Writing in 1655, Thomas Fuller suggested that “the moderation and mutual compliance of these divines might have produced much good if not interrupted.” Their suggestions for reform “might, under God, have been a means, not only to have checked, but choked our civil war in the infancy thereof.”1 A Conformist member of the sub-committee agreed with him. In his biography of John Williams, completed in 1658, but only published in 1693, John Hacket claimed that, during these meetings, “peace came... near to the birth.”2 Peter Heylyn was more critical of the sub-committee, in his biography of William Laud, published in 1671; but even he was quite clear about it importance. He wrote: Some hoped for a great Reformation to be prepared by them, and settled by the grand committee both in doctrine and discipline, and others as much feared (the affections of the men considered) that doctrinal Calvinism being once settled, more alterations would be made in the public liturgy... till it was brought more near the form of Gallic churches, after the platform of Geneva.3 A number of Non-conformists also looked back on the sub-committee as a missed opportunity.