For a Decent Order in the Church'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fifth Report Data: January 2009 to December 2015

Fifth Report Data: January 2009 to December 2015 ‘Our daughter Helen is a statistic in these pages. Understanding why, has saved others.’ David White Ngā mate aituā o tātou Ka tangihia e tātou i tēnei wā Haere, haere, haere. The dead, the afflicted, both yours and ours We lament for them at this time Farewell, farewell, farewell. Citation: Family Violence Death Review Committee. 2017. Fifth Report Data: January 2009 to December 2015. Wellington: Family Violence Death Review Committee. Published in June 2017 by the Health Quality & Safety Commission, PO Box 25496, Wellington 6146, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-908345-60-1 (Print) ISBN 978-0-908345-61-8 (Online) This document is available on the Health Quality & Safety Commission’s website: www.hqsc.govt.nz For information on this report, please contact [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Family Violence Death Review Committee is grateful to: • the Mortality Review Committee Secretariat based at the Health Quality & Safety Commission, particularly: – Rachel Smith, Specialist, Family Violence Death Review Committee – Joanna Minster, Senior Policy Analyst, Family Violence Death Review Committee – Kiri Rikihana, Acting Group Manager Mortality Review Committee Secretariat and Kaiwhakahaere Te Whai Oranga – Nikolai Minko, Principal Data Scientist, Health Quality Evaluation • Pauline Gulliver, Research Fellow, School of Population Health, University of Auckland • Dr John Little, Consultant Psychiatrist, Capital & Coast District Health Board • the advisors to the Family Violence Death Review Committee. The Family Violence Death Review Committee also thanks the people who have reviewed and provided feedback on drafts of this report. FAMILY VIOLENCE DEATH REVIEW COMMITTEE FIFTH REPORT DATA: JANUARY 2009 TO DECEMBER 2015 1 FOREWORD The Health Quality & Safety Commission (the Commission) welcomes the Fifth Report Data: January 2009 to December 2015 from the Family Violence Death Review Committee (the Committee). -

DC1-2016 (PDF , 2934Kb)

Death and Culture Conference, 2016 CONTENTS 1. CONFERENCE ORGANISERS.............................................................................. 1 MR JACK DENHAM........................................................................................................ 1 DR RUTH PENFOLD-MOUNCE ..................................................................................... 1 DR BENJAMIN POORE .................................................................................................. 2 DR JULIE RUGG ............................................................................................................. 2 2. CONFERENCE TIMETABLE................................................................................. 3 3. ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES...................................................................... 12 4. INSTALLATIONS ............................................................................................. 67 Afterlife Woodland ...................................................................................................... 67 ‘Small Histories’ Installation, 2016 ............................................................................... 68 That Which The Dying Had To Tell If We Take The Time To Listen.............................. 69 Death Becomes Her..................................................................................................... 70 5. USEFUL INFORMATION .................................................................................. 71 Public transport ............................................................................................................71 -

Estate Management in the Winchester Diocese Before and After the Interregnum: a Missed Opportunity

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 61, 2006, 182-199 (Hampshire Studies 2006) ESTATE MANAGEMENT IN THE WINCHESTER DIOCESE BEFORE AND AFTER THE INTERREGNUM: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY By ANDREW THOMSON ABSTRACT specific in the case of the cathedral and that, over allocation of moneys, the bishop seems The focus of this article is the management of the to have been largely his own man. Business at episcopal and cathedral estates of the diocese of Win the cathedral was conducted by a 'board', that chester in the seventeenth century. The cathedral is, the dean and chapter. Responsibilities in estates have hardly been examined hitherto and the diocese or at the cathedral, however, were previous discussions of the bishop's estates draw ques often similar if not identical. Whether it was a tionable conclusions. This article will show that the new bishop's palace or a new chapter house, cathedral, but not the bishop, switched from leasing both bishop and cathedral clergy had to think, for 'lives' to 'terms'. Olhenvise, either through neglect sometimes, at least, not just of themselves and or cowardice in the face of the landed classes, neither their immediate gains from the spoils, but also really exploited 'early surrenders' or switched from, of the long term. Money was set aside accord leasing to the more profitable direct farming. Rental ingly. This came from the resources at the income remained static, therefore, with serious impli bishop's disposal - mainly income from his cations for the ministry of the Church. estates - and the cathedral's income before the distribution of dividends to individual canons. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Congregational History Society Magazine Cover 2 November 2013 22:22 Page 1

Cover Autumn 2013 v1_Congregational History Society Magazine Cover 2 November 2013 22:22 Page 1 ISSN 0965–6235 Congregational History Society Magazine Volume 7 Number 2 Autumn 2013 CHC Autumn 2013 v4_CHC Autumn 2013 31 October 2013 15:13 Page 65 ISSN 0965–6235 THE CONGREGATIONAL HISTORY SOCIETY MAGAZINE Volume 7 No 2 Autumn 2013 Contents Editorial 66 News and Views 66 Correspondence 68 Notes from the Secretary 70 Obituaries 72 Elsie Chamberlain as I Knew Her 75 John Travell The Historical and Contemporary Significance of Covenant in English Congregationalism, with Particular Reference to The Congregational Federation 78 Graham Akers Review article: The Transformation of Congregationalism 1900–2000 91 Robert Pope Reviews 101 Congregational History Society Magazine, Vol. 7, No 2, 2013 65 CHC Autumn 2013 v4_CHC Autumn 2013 31 October 2013 15:13 Page 66 EDITORIAL We welcome to our pages Dr John Travell who offers us here some of his reflections upon and memories of that pioneering and influential woman minister, Elsie Chamberlain. His paper is, as he makes clear in his title, a personal insight to her character. We are also pleased to include the thoughts of Revd Graham Akers on the concept of the covenant in Congregational churches. Given his role as chair of the Congregational Federation’s pastoral care board, he is clearly interested in the application of Congregational principles in the churches. In addition we include a review article from Robert Pope who has written on The Transformation of Congregationalism 1900–2000, a new publication from the Congregational Federation. NEWS AND VIEWS The Bay Psalm Book A rare and precious but tiny hymnal, dating from 1640 and believed to be the first book actually printed in what is now the United States of America, is to be sold at auction. -

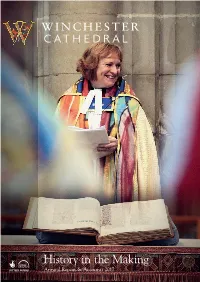

History in the Making Annual Report & Accounts 2017 Contents

History in the Making Annual Report & Accounts 2017 Contents The Dean 3 The Receiver General 5 Worship 6 Education & Spirituality 8 Canon Principal 8 A Year in View 10 The Lay Canons 12 The Cathedral Council 13 Head of Personnel 13 Architect 14 Archaeologist 14 Winchester Cathedral Enterprises Ltd. 15 Volunteering 15 Financial Report 16 The 2017 Statutory Report and Accounts are available to download from the Cathedral website and, on request, from the Cathedral Office (see back page for contact details). Front Cover: The Dean with The Winchester Bible at her installation on 11 February 2017. Images used in this report are © The Dean and Chapter of Winchester, The Diocese of Winchester, Joe Low, Dominic Parkes and Katherine Davies The Dean The historic dignity and stunning beauty of Around prayer and worship the Cathedral hosts Winchester Cathedral and its music and an increasing number of special services to serve liturgy were fully displayed on the day of my the wider communities of city, county and Installation as 38th Dean of Winchester, on diocese and visits from schools, individuals and Saturday 11 February 2017, by the Bishop of associations, including both tourists and pilgrims. Winchester. The generous welcome from None of this would be possible without the Cathedral, Diocese and County and the presence selfless work of staff and volunteers, both lay of Cathedral partners from Namirembe, and ordained. I am profoundly grateful for the Stavanger and Newcastle were deeply impressive. commitment that so many show to caring for, and The theme of Living Water flowed through the growing, the life and ministry of this place. -

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2 The Close, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LS 01962 857 245 [email protected] www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk Registered Charity No. 220218 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2020 Royal Patron Her Majesty the Queen Patron The Right Reverend Tim Dakin, Bishop of Winchester President The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester Ex Officio Vice-Presidents Nigel Atkinson Esq, HM Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire Cllr Patrick Cunningham, The Right Worshipful, the Mayor of Winchester Ms Jean Ritchie QC, Cathedral Council Chairman Honorary Vice-President Mo Hearn BOARD OF TRUSTEES Bruce Parker, Chairman Tom Watson, Vice-Chairman David Fellowes, Treasurer Jenny Hilton, Natalie Shaw Nigel Spicer, Cindy Wood Ex Officio Chapter Trustees The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester The Reverend Canon Andy Trenier, Precentor and Sacrist STAFF Lucy Hutchin, Director Lesley Mead Leisl Porter Friends’ Prayer Most glorious Lord of life, Who gave to your disciples the precious name of friends: accept our thanks for this Cathedral Church, built and adorned to your glory and alive with prayer and grant that its company of Friends may so serve and honour you in this life that they come to enjoy the fullness of your promises within the eternal fellowship of your grace; and this we ask for your name’s sake. Amen. Welcome What we have all missed most during this dreadfully long pandemic is human contact with others. Our own organisation is what it says in the official title it was given in 1931, an Association of Friends. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT STATUTORY SUPPLEMENT AND AUDITED ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2018 The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, St Peter and St Paul, and of St Swithun in Winchester Annual Report Statutory Supplement and Audited Accounts 2012017777////11118888 Contents 111 Aims and Objectives .................................................................................................. 3 222 Chapter Reports ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1 The Dean .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 The Receiver General ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Worship ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Education and Spirituality ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 2.5 Canon Principal ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Diocesan Synod Digest

DIOCESAN SYNOD ACTS 16 March 2017 Acts of the Diocesan Synod held on 16 March 2017 at St Luke’s Hedge End. 70 members were in attendance. The Revd Fiona Gibbs and Mr Nigel Williams led members in opening worship. The Bishop of Winchester welcomed members. AMAP PROPOSALS 2017-1019, DS 17/01 Vision & Implementation of Strategic Priorities The Bishop of Winchester shared an overview of the vision and implementation of the diocesan strategic priorities at a diocesan and archidiaconal level, focusing on sustainable growth for the common good, with the intention to be proactive rather than reactive. Four projects were proposed: 1. Benefice of the Future, Promote Rural Evangelism & Discipleship The Archdeacon of Winchester presented proposals for the Benefice of the Future to be trialled in three benefices initially: Pastrow with Hurstbourne Tarrant & Faccombe & Vernham Dean & Linkenholt; North Hampshire Downs; Avon Valley. 2. Invest Where There is the Greatest Potential for Numerical Growth – Resource Churches Planted, Flourishing and Preparing to Plant Again The Archdeacon of Bournemouth presented proposals for Resource Churches, with initial plans to go into Southampton and Basingstoke, each Resource Church to develop a pipeline to plant other churches. 3. Major Development Areas (MDA) – the Church Supports Sustainable Community Development and Offers a Missional Christian Presence The Bishop of Basingstoke presented an overview of areas across the diocese which will see developments of 250+ houses over the next few years; proposing that the diocese must engage with the new communities as soon as possible to ensure a Christian presence. 4. Further & Higher Education – Grow and Deepen the Church’s Engagement with Students and Institutions The Bishop of Winchester presented members with an overview of Further and Higher Education and the challenges the church faces with engagement. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Saint James Chapel, Exeter College, University of Oxford

case study 5 Saint James Chapel, Exeter College, University of Oxford 1624 Private chapel (university college) New chapel by George Gilbert Scott, 1856–91 Architect unknown Historical note Exeter College is one of the oldest colleges of Oxford University, founded in 1314 by the bishop of Exeter, Walter de Stapledon, but for the first 250 years of its existence it was also one of the smallest.2 Exeter College remained a strong adherent to the Roman Catholic ‘old’ worship partly no doubt because it drew most of its members from the conservative counties of the far west, where Protestantism was slow to gain ground. In 1578 because of these Catholic ten- dencies several fellows were removed and a new rector, Thomas Holland, ap- pointed by Royal Commission. This purge, combined with the gradual shift in west-country allegiances during the late sixteenth century from Catholicism to Protestantism, changed the whole character of the college. By the early seven- teenth century Exeter College had become notable for the Puritan inclinations of its membership.3 And by 1612 Exeter had become one of the largest colleg- es of university, with 134 commoners. Due to this growth the most important building activity took place between 1616 and 1710, including the hall, the cha- pel, and buildings on the south-east of the quad, all built under the rectorship of John Prideaux, between 1612 and 1642. However, financial difficulties arose in 1675. A visitation carried on the orders of the bishop of Exeter “found that too 1 Historic England, Images of England record 244921.