Two Sixteenth-Century Taxation Lists, 1545 and 1576

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

ALDBOURNE Parish

WILTSHIRE COUNCIL WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS APPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT RECEIVED IN WEEK ENDING 19/02/2021 Parish: ALDBOURNE Electoral Division: ALDBOURNE AND RAMSBURY Application Number: 21/00891/FUL Grid Ref: 426446 175108 Applicant: Mr Ben Jackson Applicant Address: 3, The Garlings Aldbourne SN8 2DT Site Location: 3 The Garlings Aldbourne SN8 2DT Proposal: Single storey front extension and garage extension. Case Officer: Helena Carney Registration Date: 15/02/2021 Direct Line: 01225 770334 Please send your comments by: 15/03/2021 Electoral Division: ALDBOURNE AND RAMSBURY Application Number: 21/01004/OUT Grid Ref: 426713 176388 Applicant: . Applicant Address: DAMMAS HOUSE DAMMAS LANE SWINDON SN3EF Site Location: Land at Lottage Farm Lottage Road Aldbourne SN8 2ED Proposal: Outline planning application for up to 32 Dwellings, Public Open Space, Landscaping and Associated Engineering Works Case Officer: Nick Clark Registration Date: 18/02/2021 Direct Line: 01225 770258 Please send your comments by: 25/03/2021 Electoral Division: ALDBOURNE AND RAMSBURY Application Number: 21/01411/FUL Grid Ref: 426654 176160 Applicant: Mr Richard Flynn Applicant Address: Westways Kandahar Aldbourne Wiltshire SN8 2EE Site Location: Westways Kandahar Aldbourne Wiltshire SN8 2EE Proposal: Part demolition of existing dwelling, infill extensions with a new first floor extension, re-modelling of dwelling to ceate a new 4 bedroom layout Case Officer: Lucy Rutter Registration Date: 13/02/2021 Direct Line: 01225 716546 Please send your comments by: 15/03/2021 Parish: ALDERBURY Electoral Division: ALDERBURY AND WHITEPARISH Application Number: 21/00636/VAR Grid Ref: 418473 127049 Applicant: Mr Phil Smith Applicant Address: Woodlynne Lights Lane Alderbury Salisbury Wiltshire SP5 3DS Site Location: Woodlynne House Lights Lane Alderbury Salisbury Wiltshire SP5 3DS Proposal: Variation of Condition 12 of S/10/0001 to allow amended design and siting (Demolish existing suburban dwelling and replace with a new country dwelling of traditional proportions). -

Memorials of Old Wiltshire I

M-L Gc 942.3101 D84m 1304191 GENEALOGY COLLECTION I 3 1833 00676 4861 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldwiOOdryd '^: Memorials OF Old Wiltshire I ^ .MEMORIALS DF OLD WILTSHIRE EDITED BY ALICE DRYDEN Editor of Meinoriah cf Old Northamptonshire ' With many Illustrations 1304191 PREFACE THE Series of the Memorials of the Counties of England is now so well known that a preface seems unnecessary to introduce the contributed papers, which have all been specially written for the book. It only remains for the Editor to gratefully thank the contributors for their most kind and voluntary assistance. Her thanks are also due to Lady Antrobus for kindly lending some blocks from her Guide to Amesbury and Stonekenge, and for allowing the reproduction of some of Miss C. Miles' unique photographs ; and to Mr. Sidney Brakspear, Mr. Britten, and Mr. Witcomb, for the loan of their photographs. Alice Dryden. CONTENTS Page Historic Wiltshire By M. Edwards I Three Notable Houses By J. Alfred Gotch, F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A. Prehistoric Circles By Sir Alexander Muir Mackenzie, Bart. 29 Lacock Abbey .... By the Rev. W. G. Clark- Maxwell, F.S.A. Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers . By H. St. George Gray The Rising in the West, 1655 . The Royal Forests of Wiltshire and Cranborne Chase The Arundells of Wardour Salisbury PoHtics in the Reign of Queen Anne William Beckford of Fonthill Marlborough in Olden Times Malmesbury Literary Associations . Clarendon, the Historian . Salisbury .... CONTENTS Page Some Old Houses By the late Thomas Garner 197 Bradford-on-Avon By Alice Dryden 210 Ancient Barns in Wiltshire By Percy Mundy . -

Prayer Cycle March 2021.Pdf

The Lord calls us to do justly, love mercy and walk humbly with God - Micah 6:8 st 1 - St David, Bishop of Menevia, Patron of Wales, c.601 Within our Congregation and Parish: Pam and Sarah Annis, Sue and Terence Tovey, Catherine Woodruff, John Yard All Residents and Visitors of Albert Terrace, Bridewell Street, Hare and Hounds Street, Sutton Place and Tylees Court Those who are frightened in our Parish 2nd – Chad, Bishop of Lichfield, Missionary, 672 Within our Congregation and Parish: Gwendoline Ardley, Richard Barron, Catherine Tarrant, Chris Totney All Residents and Visitors of Broadleas Road, Broadleas Close, Broadleas Crescent, Broadleas Park Within our Parish all Medical and Dental Practices Those who need refuge in our Parish rd 3 Within our Congregation and Parish: Mike and Ros Benson, John and Julia Twentyman, David and Soraya Pegden All Residents and Visitors of Castle Court, Castle Grounds, Castle Lane Within our Parish all Retail Businesses Those who fear in our Parish 4th Within our Congregation and Parish: Stephen and Amanda Bradley, Sarah and Robin Stevens All Residents and Visitors of New Park Street, New Park Road, Chantry Court, Within our Parish all Commercial Businesses and those who are lonely Those who are hungry in our Parish 5th Within our Congregation and Parish: Judy Bridger, Georgina Burge, Charles and Diana Slater. All Residents and Visitors of Hillworth Road, Hillworth Gardens, Charles Morrison Close, John Rennie Close, The Moorlands, Pinetum Close and Westview Crescent Within our Parish all Market Stalls and Stall Holders Those who are in need of a friend in our Parish th 6 Within Churches Together, Devizes: The Church of Our Lady; growing confidence in faith; introductory courses; Alpha, Pilgrim and ongoing study, home groups. -

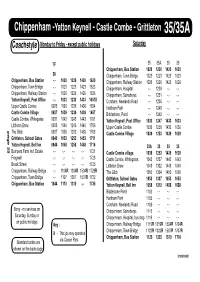

35/35A Key: Y

Chippenham - Kington St Michael 99 Monday to Friday - except public holidays Coachstyle Faresaver Service number 35 Chippenham, Bus Station -.- -.- 0920 1015 1115 1315 1415 -.- 1620 1745 Chippenham, Town Bridge 0718 0818 0923 1018 1118 1318 1418 1508 1623 1748 Chippenham, Railway Sation 0721 0821 0925R 1021R 1121R 1321R 1421R -.- 1626 1751 Sheldon School (school days only) -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- -.- 1510 -.- -.- Monkton Park, Lady Coventry Road -.- -.- -.- 1023 1123 1323 1428 -.- -.- 1753R Chippenham, Railway Station 0721 0821 0925R 1025 1125 1325 -.- -.- 1626 1755 Bristol Road 0724 0824 0927 1027 1127 1327 -.- 1511 -.- 1757 Brook Street -.- 0825 0928 1028 1128 1328 -.- -.- -.- -.- Redland -.- 0826 0929 1029 1129 1329 -.- -.- -.- -.- page 64 Frogwell 0728R 0828 0931 1031 1131 1331 -.- -.- -.- -.- Bumpers Farm Industrial Estate 0730R 0830R 0933 1033 1133 1333 -.- -.- -.- -.- Cepen Park, Stainers Way 0732 -.- 0935 1035 1135 1335 -.- 1518 1636 1801 Morrisons Supermarket 0735 -.- 0938 1038 1138 1338 -.- 1521 1639 1804 Kington St Michael, bus shelter 0740 -.- 0943 1043 1143 1343 -.- 1526 1644y 1809R 35 Key: Kington St Michael, bus shelter 0745 0845 0945 1045 1145 1345 -.- 1545 -.- y - Bus continues Morrisons Supermarket 0752 0852 0952 1052 1152 1352 -.- 1552 -.- to Yatton Keynell Cepen Park, Stainers Way 0754 0854 0954 1054 1154 1354 -.- 1554 -.- Bumpers Farm Industrial Estate -.- 0856 0956 1056 1156 1356 -.- 1556 1721 Frogwell -.- 0858 0958 1058 1158 1358 -.- 1558 1723 See next page for Brook Street 0800 0900R 1000R 1100R 1200R 1400R -.- -

Ridgeway 2015.Cdr

DUNSTABLE The Ridgeway NATIONAL TRAIL Eaton Bray B4541 The Ridgeway National Trail is the 87-mile central section, between Ivinghoe Beacon B4540 in the Chilterns, and the Avebury World Heritage Site in Wiltshire, of an ancient trade Ivinghoe Beacon B489 route along the chalk downs stretching from Norfolk to the Dorset coast. A4146 AYLESBURY A41 B488 Coombe Hill Tring A413 B4506 A4251 Wendover A4010 A4129 A41 B4009 BERKHAMSTED B4445 Princes Risborough A413 M40 A40 Chinnor Great Missenden Prestwood Barbury Castle Watlington market town B4009 White Horse Hill Lewknor A4010 B480 ABINGDON Stokenchurch A34 Watlington A40 River Thames B4009 The Ridgeway Partnership Milton M40 Benson DIDCOT Grove The Partners A417 Wallingford The Lead Partner (accountable body) - Oxfordshire A417 A4130 B480 County Council Hackpen Hill Shrivenham B481 B4016 Other local authorities:- B4507 A4185 WANTAGE Cholsey Buckinghamshire County Council A420 Hertfordshire County Council B4000 Blewbury SWINDON Nettlebed Oxfordshire County Council Chilton A329 A4130 A4074 Swindon Borough Council A419 B4009 Wiltshire Council M4 Wanborough B4494 West Berkshire Council A4259 B4001 A338 Natural England Goring North Wessex Downs AONB Wroughton B4005 Chilterns Conservation Board Compton Stakeholders:- A34 B4526 Chiseldon Lambourn Amenity Chiltern Society A417 B4192 River Thames Archaeology B4009 Cyclists Sustrans and Mountain Biking Clubs Pangbourne A4361 A346 M4 Environment Natural England Landowners Country Landowners Association north Aldbourne Equestrians British Horse Society -

Character Index

Surname Alt / Maiden / etc Given name/s Census / PR / info Notes Adela HELYAR ? Ann Upper Housemaid at Ferne, 1828 Ann Ferne Dairymaid (pre 1818) Lost a child. Milkwell. Married the Shepherd Annie Deaf girl, possibly WALSH Aaron Footman at Ferne 1825 Capt. Bertie Possibly MARKLAND's brother ? 1815 Betsey Wet nurse at Coker, 1813 Betty Harriet's housemaid, 1814. Friend of Susan at Ferne? Billy Poss. OGLE. 1812 Daniel an old gardener at Coker, 1823 Daniel Married to Jane 1824 ? Daniel in service to Thos. GROVE snr Edie Surname? EDIES cottage, 1817. Female Hannah maid to Mrs WHITE (Ludwell) 1823, 1825 Humphrey "friend" of Miss LYPSCOMBE ? 1812 Miss Jemima Poss. ARUNDEL, 1816 James "James drove us to Wincombe……" 6 9 1825. Servant? Jane Married to Daniel 1824 ? John Possibly WARNER Judith niece of Wm the Conqueror (Cowper's Oak) Maria Nurse (at Ferne?) 1828. "Sad business" Maria Aunt Chafin GROVE's "faithful maid", 1833 Martha Servant of Harriet GROVE ? 1820 Marianne Poss. WADDINGTON, June 1819 Mary Niece of Mrs COCKRAM Mary TM m. Wm LUSH 1843 Matilda Servant ? In 1818 Missy JACKSON, 1812. servant ? SCAMMELL Molly Servant of Old Mr LUSH, Easton Molly Burlington St, London, 1824. Servant Probably prev. nurse to WADDINGTON family. "Old Molly" 1828, Marwell Moses Carriage 1818. 14 miles 1824. Cakes 1825. Servant to Aunt GROVE?+E166 SISTER Placida Nun at Wardour 1814 Prudence Charlotte's housemaid 1823 Rachel Poss. SELLWOOD, or a servant / maid, 1813, Sedgehill Sally Housemaid (Ferne), came back in 1819, ill in 1821 Sarah Maid to Mary GROVE Surname Alt / Maiden / etc Given name/s Census / PR / info Notes Septimus Possibly WARNER (Old) Susan Henstridge area, 1826 Susan Nurse girl of WADDINGTON'S, 1820. -

Britford - Census 1851 Includes Alderbury Union Workhouse

Britford - Census 1851 Includes Alderbury Union Workhouse Year Address Surname Given Names Position Status Age Sex Occupation Place of Birth Notes Born HO107/1846 1 Cookman John Head M 71 M 1780 Agrtultural Laborer Britford Page 1. ED2a, folio 354 Cookman Ann Wife M 60 F 1791 Banton, Oxford Cookman Thommas Son U 15 M 1836 Ag Lab Britford 2 Rumbold William Head M 68 M 1783 Carter Boscomb Rumbold Mary Wife M 66 F 1785 Wishford Rumbold William Son M 30 M 1821 Ag Lab Dog Dean Rumbold Leah Daughter U 25 F 1826 Shepherdess x-out, At Home Dog Dean 3 Waters Thommas Head M 37 M 1814 Shepherd Bake Farm Waters Rossanna Wife M 42 F 1809 Salisbury Waters William Son 14 M 1837 Shepherd Boy Hommington Waters Enos Son 12 M 1839 At Home Well House Waters John Son 10 M 1841 At Home Well House Waters Susanne Daughter 7 F 1844 At Home Well House Waters Rosanna Daughter 4 F 1847 Well House Waters George Son 3 M 1848 Well House Waters James Son 0 M 1851 Well House 5 Mnths 4 Waters Thommas Head M 32 M 1819 Ag Lab Bake Farm, Wilts. Waters Jane Wife M 33 F 1818 Longford Waters Elizabeth Daughter 3 F 1848 Bake, Wilts Waters Ruth Daughter 0 F 1851 Bake, Wilts Age 10 mths 5 Webb James Head M 53 M 1798 Carter Downton Page 2 Webb Hannah Wife M 55 F 1796 Charlton Webb George Son M 24 M 1827 Ag Lab Hommington Webb William Son U 20 M 1831 Ag Lab Well House Webb Robert Son U 18 M 1833 Shepherd Bake Farm Webb Charles Son 15 M 1836 Shepherd Boy Bake Farm Webb Ann Daughter 12 F 1839 At Home Bake Farm Webb Dinah Granddaughter 5 F 1846 At Home Bake Farm Small James Father -

WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End Mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY. J WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs. Jas. Whiteparish, Salisbury St. Andrew, Salisbury Smith William, Broad Hinton, Swindon Strong George, Rowde, Devizes Sharpe Mrs. Henry, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William, Winsley, Bradford Strong James, Everleigh, Marlborough Sharpe Hy. Samuel, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William Hugh, Harpit, Wan- Strong Willialll, Draycot, Marlborough Sharps Frank, South Marston, Swindon borough, ShrivenhamR.S.O. (Berks) Strong William, Pewsey S.O Sharps Robert, South Marston, Swindon Snelgar John, Whiteparish, Salisbury Stubble George, Colerne, Chippenham Sharps W. H. South Marston, Swindon Snelgrove David, Chirton, De,·izes Sumbler John, Seend, Melksham Sheate James, Melksham Snook Brothers, Urchfont, Devizes SummersJ.&J. South Wraxhall,Bradfrd Shefford James, Wilton, Marlborough Snook Albert, South Marston, Swindon Summers Edwd. Wingfield rd. Trowbrdg ShepherdMrs.S.Sth.Burcombe,Salisbury Snook Mrs. Francis, Rowde, Devizes Sutton Edwd. Pry, Purton, Swindon Sheppard E.BarfordSt.Martin,Salisbury Snook George, South Marston, Swindon Sutton Fredk. Brinkworth, Chippenham Shergold John Hy. Chihnark, Salisbury EnookHerbert,Wick,Hannington,Swndn Sutton F. Packhorse, Purton, Swindon ·Sbewring George, Chippenham Snook Joseph, Sedghill, Shaftesbury Sutton Job, West Dean, Salisbury Sidford Frank, Wilsford & Lake farms, Snook Miss Mary, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton·John lllake, Winterbourne Gun- Wilsford, Salisbury Snook Thomas, Urchfont, Devizes ner, Salisbury "Sidford Fdk.Faulston,Bishopstn.Salisbry Snook Worthr, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton Josiah, Haydon, Swindon Sidford James, South Newton, Salisbury Somerset J. Milton Lilborne, Pewsey S.O Sutton Thomas Blake, Hurdcott, Winter Bimkins Job, Bentham, Purton, Swindon Spackman Edward, Axrord, Hungerford bourne Earls, Salisbury Simmons T. GreatSomerford, Chippenhm Spackman Ed. Tytherton, Chippenham Sutton William, West Ha.rnham,Salisbry .Simms Mrs. -

Littlehome Berwick St John - Wiltshire

Littlehome Berwick St John - Wiltshire Littlehome Water Street Berwick St John Shaftesbury SP7 0HS An absolutely idyllic country cottage situated in a lovely rural village setting that has been extended & refurbished to an exemplary standard with stylish contemporary fittings ● Located at the Head of the Chalke Valley ● Open Plan Living Space ● Bespoke Fitted & Equipped Kitchen Area Situation The property is situated on a small lane of pretty cottages and houses in the highly desirable rural village of ● Two Charming Bedrooms Berwick St John and is surrounded by glorious countryside. This attractive community is located at the head of the Chalke Valley and in the lee of the undulating downland of the Cranborne Chase on the Wiltshire/Dorset border with Win Green, ● Superbly Appointed Wet Room a local beauty spot known for its spectacular views, close by. The village has a 14th Century church and a highly rated 17th Century dining pub, The Talbot Inn. Ludwell is three miles away and has an excellent store/post office which has won the ● Ample Parking & Outbuilding/ Garage accolade of Britain’s best village shop, an award-winning butcher, a primary school and two pubs. ● Raised Garden with Views The larger village of Tisbury and the Saxon hilltop market town of Shaftesbury are both around six miles away, each offering a good choice of independent shops, boutiques and eateries with amenities including sports centres and medical facilities. Viewing strictly by appointment via The former also has a station with direct rail services to London (Waterloo) and is home to Messums Wiltshire whilst the Sole Agents Rural View (Salisbury) Ltd latter is famed for the steeply cobbled street of Gold Hill and has a well-regarded secondary school. -

From 1 September 2020

from 1 September 2020 routes Calne • Marlborough via Avebury 42 Mondays to Fridays except public holidays these journeys operate via Heddington Wick, Heddington, Calne The Pippin, Sainsbury's 0910 1115 1303 1435 1532 1632 1740 Stockley and Rookery Park. They also serve Yatesbury to set Calne Post Office 0911 0933 1116 1304 1436 1533 1633 1741 down passengers only if requested and the 1532 and 1740 Calne The Strand, Bank House 0730 0913 0935 1118 1306 1438 1535 1635 1743 journey will also serve Blacklands on request Kingsbury Green Academy 1537 1637 these journeys operate via Kingsbury Quemerford Post Office 0733 0916 0938 1121 1309 1441 R R R Green Academy on schooldays only Lower Compton Turn (A4) 0735 0918 0940 1123 1313 1443 R R R Lower Compton Spreckley Road 0942 R 1315 R R R Compton Bassett Briar Leaze 0948 R 1321 R R Cherhill Black Horse 0737 0920 1125 1329 1445 R R R Beckhampton Stables 0742 0925 1130 1334 1450 R R R Avebury Trusloe 0743 0926 1131 1335 1451 R R R Avebury Red Lion arrive 0745 0928 1133 1337 1453 R R R Winterbourne Monkton 0932 R Berwick Bassett Village 0935 R Avebury Red Lion depart 0745 0940 1143 1343 1503 1615 1715 West Kennett Telephone Box 0748 0943 1146 1346 1506 1618 1718 East Kennett Church Lane End 0750 0945 1148 1348 R R West Overton Village Stores 0753 0948 1151 1351 R R Lockeridge Who'd A Thought It 0757 0952 1155 1355 R R Fyfield Bath Road 0759 0954 1157 1357 1507 1621 1726 Clatford Crossroads 0801 0957 1200 1400 R Manton High Street 0803 0959 1202 1402 R Barton Park Morris Road, Aubrey Close 0807 0925 1003 1205 1405 1510 R R Marlborough High Street 0812 0929 1007 1210 1410 1515 1630 1740 Marlborough St Johns School 0820 serves Marlborough operates via these journeys operate via Blacklands to St Johns School on Yatesbury to set set down passengers only if requested. -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No.